- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: Windows

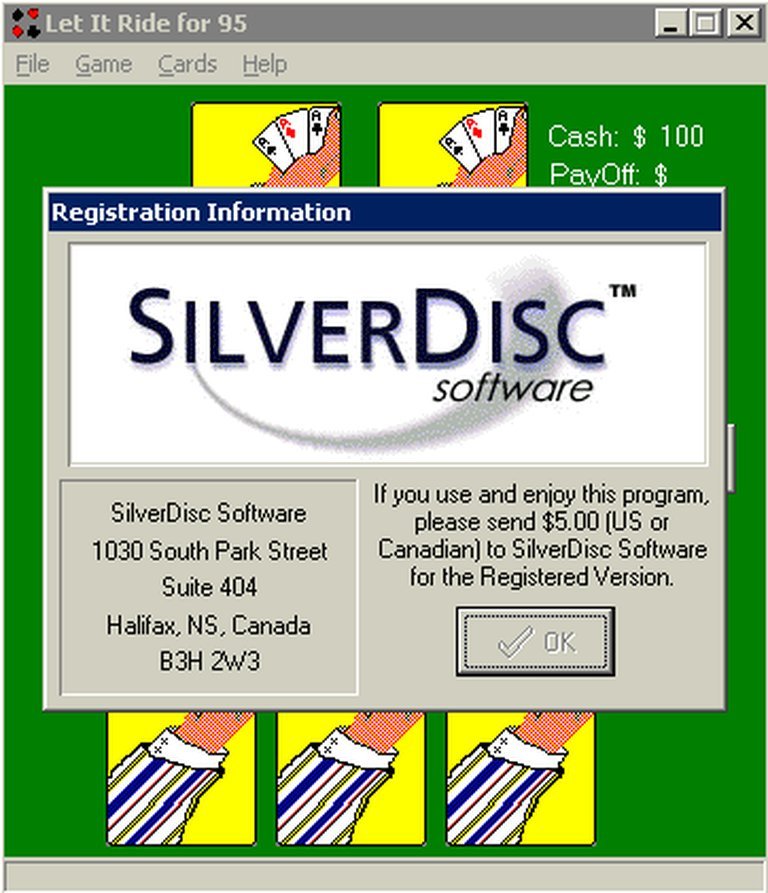

- Developer: SilverDisc Software

- Genre: Gambling, Strategy, Tactics

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Betting, Card game, Poker

Description

Let It Ride for 95 is a single-player, shareware card game for Windows 95 that adapts the casino poker variant Let It Ride. Players are dealt three face-up cards and two face-down dealer cards, with three opportunities to bet as cards are revealed. The goal is to achieve a winning poker hand of at least a pair of tens, causing all three wagers to pay out; otherwise, all bets are lost.

Let It Ride for 95 Free Download

Let It Ride for 95 Reviews & Reception

reviewbasement.blogspot.com : We took turns of course, but it was alot of fun.

Let It Ride for 95: Review

Introduction: A Digital Dust Gem in the Windows 95 Card-Shuffle Era

In the sprawling, hyper-accelerated landscape of 1996 video games—a year that birthed Super Mario 64, Tomb Raider, Resident Evil, and Quake—the existence of Let It Ride for 95 is both a profound footnote and a testament to the era’s boundless, indiscriminate digitization of everything. While the world was being introduced to 3D polygonal worlds and CD-ROM adventures, a tiny shareware studio named SilverDisc Software quietly released a pixel-perfect, mouse-driven simulation of a then-novel Las Vegas table game. This review argues that Let It Ride for 95 is not a lost classic, nor a broken experiment, but a fascinatingly pure artifact of a specific moment: the moment when the personal computer became a legitimate, if austere, platform for gambling simulations. Its value lies not in innovation or artistry, but in its stark, unadorned functionality—a digital translation of a casino game stripped of all spectacle, leaving only cold probability and minimalist interaction. To understand it is to understand a sliver of 1990s shareware culture, the nascent PC casino game niche, and the peculiar appeal of games that ask almost nothing of the player beyond simple arithmetic and nerve.

Development History & Context: The Shareware Gambit in a Year of Revolution

The Studio and the Vision: SilverDisc Software is a phantom. Beyond this single title and a mention of “PROTO for Windows 95” as a related game in the MobyGames database, the studio leaves no digital footprint. This suggests a classic 1990s shareware outfit: likely a small team or even a solo developer operating on a shoestring, targeting the vast, unfiltered market of Windows 95 users downloading games from CompuServe, AOL, or early internet hubs. Their vision was not to revolutionize gaming but to capitalize on a trend: the migration of casino games from physical floors to desktop monitors. The choice of Let It Ride was astute. As detailed in the Global Casino Guide source, the real-world game had exploded in popularity after its 1993 invention by John Breeding (to promote his Shuffle Master machines). By 1995-1996, it was a staple on the Las Vegas Strip, lauded for its player-friendly “let it ride” mechanic (the ability to pull back bets) and slower reveal. SilverDisc saw a low-risk, rules-based game perfectly suited for digital translation.

Technological Constraints & The Windows 95 Playground: The game was built for Windows 95, a period of transition. The OS’s graphical user interface was still novel for many, and “multimedia” often meant MIDI music and 256-color SVGA graphics. The source from the Internet Archive describes the game as a mere 417.6KB—a size that speaks volumes. This is not a game of pre-rendered 3D or CD-quality audio. It is a collection of bitmapped card graphics, simple UI elements (likely GDI-drawn rectangles for betting circles), and event-driven code. The constraint was not pushing hardware limits but achieving absolute compatibility and minimalism. The instruction “The game is played entirely with the mouse” is not a feature but a necessity; keyboard support would have added unnecessary complexity. It is a game designed for the 486/early Pentium user, loading instantly, running in a window, and demanding negligible system resources.

The 1996 Gaming Landscape: This is the critical context. As the Wikipedia “1996 in video games” page enumerates, the year was defined by seismic shifts: the launch of the Nintendo 64 and its flagship Super Mario 64, the PlayStation’s dominance with Resident Evil and Tekken 2, the PC’s revolution with 3D shooters (Quake, Duke Nukem 3D) and strategy (Civilization II). Against this backdrop of immersive worlds, complex narratives, and technical awe, Let It Ride for 95 represents the absolute antithesis. It is a “process game,” not a “world game.” Its competition was not Mario or Lara Croft, but other digital table games like Microsoft Reversi or Hoyle Casino. It existed in a parallel universe of gaming, one concerned with replicating rulesets, not creating experiences. Its shareware model was a direct pipeline to an audience that might have been playing the physical version in a casino or on a home poker night, now seeking a solitary, anonymous practice ground on their PC.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absence of Story as a Statement

Let It Ride for 95 possesses a narrative in the same way a spreadsheet possesses a narrative: it is implicit in the structure of its operations. There is no plot, no characters, no dialogue, no setting beyond the abstract green felt of the virtual table. This is not a failing but a fundamental design principle. The game’s “story” is the eternal, mathematical drama of risk versus reward played out in three acts:

- The Ante of Agency: The player receives three cards. This is the moment of first information. The thematic core here is knowledge as power and vulnerability. You see a partial hand. The game mechanically asks: “Do you have enough to continue? Do you reduce your exposure now?” The theme is the burden of early decision-making under uncertainty.

- The Community Card Revelation: The dealer reveals the first of two hidden cards. The hand’s potential shifts. The player must reassess. The theme evolves into adaptive strategy. The initial bet placed in Act 1 is now at stake. Do you trust the first community card to complete a hand, or do you pull a second bet, hedging against a weak final card? This is the game’s central psychological tension—the interplay between hope and statistical reality.

- The Final Card and The Abacus of Fate: The second dealer card is revealed. The five-card hand is finalized. The only “narrative” resolution is a binary payout screen: trio of winning bets added to a virtual stack, or the three bets vanish. The theme resolves to probabilistic determinism. There is no underdog story, no last-second save. The cards are what they are. The outcome was statistically determined the moment the final card was dealt, and the player’s mid-game decisions merely optimized or pessimized the financial result.

The “characters” are the player’s own temperament—the cautious grinder, the reckless optimist, the cold calculator. The game is a Skinner box for the probabilistic mind, a silent, relentless tutor in the house edge. Its utter lack of traditional narrative makes it a unique case study: a game that is purely about systems and player-state interaction. The theme is the cold, beautiful arithmetic of chance.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Deconstructing the Three-Bet Engine

The brilliance and limitation of Let It Ride for 95 are contained within its 30-word ruleset from MobyGames: “Five cards are dealt, three are dealt face-up to the player and two are dealt face-down to the dealer… The player has three chances to bet… If the five cards make a winning hand then all three wagers pay out, if they do not make a winning hand then all three wagers are lost.”

Core Loop & Strategic Depth: The loop is hypnotically simple:

1. Place three equal bets (the game’s shareware version likely forces a fixed bet amount).

2. Receive three player cards (face-up).

3. Decision Point 1: Option to “Pull” (retrieve) the first bet or “Let It Ride.”

4. Dealer reveals first community card.

5. Decision Point 2: Option to “Pull” the second bet or “Let It Ride.”

6. Dealer reveals second (and final) community card.

7. Resolution: Final 5-card hand evaluated. Winning hand (pair of 10s or better) pays all remaining bets (1:1 for a pair, up to 1000:1 for a royal flush, per standard casino rules). Losing hand forfeits all remaining bets.

The strategic depth emerges from the two pull decisions. Optimum play, as derived from the real-world game’s basic strategy, is a matter of conditional probability. Do you pull after your first three cards? Generally, only with absolutely nothing (less than a pair of 10s) or perhaps a very low suited connector. After the first community card, the decision matrix expands based on whether you now have a made hand (pair, two pair, trips) or a strong draw (four to a flush, four to an open-ended straight). The game is a elegant exercise in risk management, where the “house edge” (approx. 3.5% per Global Casino Guide) is combated not through card counting (impossible with a continuously shuffled single deck in the real game, and simulated here), but through optimal bet preservation.

Systems & Innovations: The game’s single, paramount innovation is the three-betting-round, pull-back mechanic. This was revolutionary for casino games in the 1990s, giving players a rare sense of control over their exposure. In the digital translation, this becomes a pure algorithm. The “Innovative” aspect is the seamless, rule-accurate implementation. The “Flawed” aspect is the total absence of any meta-game. There is no bankroll management over sessions, no varying bet sizes, no statistics beyond the immediate hand. It is a perfect, isolated simulation of one hand, repeated.

UI & Interaction: The “entirely with the mouse” control is perfect for the format. Click a circle to bet/place chips (visually represented). Click “Let It Ride” or “Pull” buttons. The UI is likely a static screen with three betting circles for the player, a dealer card area, and a status display. It is the epitome of point-and-click simplicity, requiring no reading of manuals if one knows poker hands. Its flaw is its complete lack of feedback or education—no strategy hints, no hand probability calculator, nothing to elevate it beyond a mechanical replica.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of the Void

Given the source material, the game’s aesthetic presentation must be inferred from its context and size. A 417KB Windows 95 shareware title could not afford lavish assets.

Visual Direction: The world is a single, top-down, fixed perspective of a green rectangle (the felt). The cards are likely standard, pixel-art interpretations of a 52-card deck, possibly using the simple Windows “card” font or a basic bitmap set. The dealer is not a character but a designated area on the screen. The atmosphere is not “casino” but “utility.” There is no carpet, no chandeliers, no other players at the table. The “world” is a抽象 (chūshō) space of colored pixels representing cards and chips. This minimalism accidentally creates a unique, almost meditative tension. The only visual drama comes from the card flips—simple animation cycles where a back-of-card graphic is replaced by the face graphic. The setting is not a casino; it is a probabilistic engine made visible.

Sound Design: We can assume the soundscape is either nonexistent or consists of 8-bit, .WAV-file snippets: a card “shuffle” (more likely a simple noise), a chip “clink,” and perhaps a monotonous synthesized voice or text-to-speech alert saying “Let it ride” or “Winner!” The absence of a musical track is almost certain. The sound design, if present, would serve purely functional feedback purposes, reinforcing the sterile, process-oriented nature of the experience. Any attempt at immersive casino ambiance would have blown the file size budget.

Contribution to Experience: These elements conspire to create an experience that is profoundly un-casino-like. Real casinos are sensory overloads: noise, light, crowds, alcohol, the palpable tension of other players. Let It Ride for 95 is the opposite: a silent, solitary, brightly-lit box on a monitor. The tension comes not from the environment but from the silent dialogue between the player’s mind and the numbers on the screen. The art and sound, in their utter simplicity, force the player to engage solely with the game’s mathematical heart. It is world-building by radical subtraction.

Reception & Legacy: An Echo in a Cathedral

Contemporary Reception (1996): There is no record of any critic or player review from the time. The MobyGames page, our primary source, shows zero critic reviews and a “Moby Score” of N/A. It has been collected by only three players as of 2023. This indicates near-total obscurity at launch and throughout its lifecycle. It would have been one of thousands of shareware titles flooding the nascent online distribution channels, lost in the shadow of the year’s mega-hits. Its commercial success was likely microscopic, enough to cover the developer’s costs but nowhere near the stratospheric revenues of the physical Let It Ride tables (which, per Global Casino Guide, were already generating more than the Shuffle Master machines by 1995).

Evolution of Reputation: The reputation has not evolved; it has remained static at “obscure shareware curio.” It is occasionally discovered by digital archaeologists and casino game enthusiasts. Its legacy is entirely derivative: it is a competent, early digital version of a popular casino game. Its significance is historical, not artistic.

Influence: Direct influence is negligible. It did not pioneer a genre (digital casino games predated it, e.g., Hoyle Casino series). It did not inspire clones because the real Let It Ride was already widely licensed, and more polished, commercial digital versions followed (like Snap! Let It Ride in 2004, which itself is noted as having “faithful recreation” but lacking innovation). Its influence is as a proof of concept: it demonstrated that a complex-betting-round casino game could be faithfully and efficiently rendered as a Windows 95 shareware application. It paved the way for the countless $9.99 “Casino Package” games of the late 1990s and early 2000s by validating the market for single-game, rules-focused simulations.

Position in Industry History: Let It Ride for 95 belongs to a now-almost-extinct category: the non-toy, non-narrative, single-rule-set utility game. In 1996, games were striving to be ” experiences.” This game aimed only to be a tool. Its lineage traces back to early computer implementations of board games like Chess or Reversi, but with a modern (for the time) GUI. It represents a branch of game development that prioritized simulation accuracy over entertainment value, a branch that would largely be subsumed by either serious “training” software or the minimalist “chill” games of the 2010s (e.g., Magnetica, Meteos). It is a snapshot of the PC as a versatile, general-purpose machine, capable of hosting anything from a 3D shooter to a perfect digital replica of a poker derivative.

Conclusion: The Unassuming Variable in the Equation of 1996

Let It Ride for 95 is not a game to be loved. It offers no charm, no challenge beyond optimal play memorization, no aesthetic rewards. Its verdict in the court of history must be one of stark, clinical assessment. It is a technically competent, historically interesting, but creatively barren adaptation.

Its place in video game history is not on a pedestal but in a display case labeled “Ephemera of the Shareware Era.” It is valuable as a primary source document. Looking at its 417KB package, its mouse-only interface, and its total encapsulation of a single casino game’s rules, we see the DNA of an entire category of software that flourished in the 1990s: the disposable, downloadable, single-interest application. It was the Solitaire of casino games for a certain niche of user—the person who wanted to practice poker-side-game strategy without social pressure or the flash of a full Hoyle suite.

The ultimate irony is that the real-world Let It Ride game it simulates is a tale of explosive, billion-dollar commercial success. The digital version, Let It Ride for 95, is a ghost. It is the sound of one hand clapping in a server room, a perfectly rendered algorithmic echo that was almost certainly played by fewer people in its entire lifespan than the number of hands of real Let It Ride dealt on the Las Vegas Strip in a single hour on a Saturday night. Its genius is in its ruthless, unflinching simplicity. Its tragedy is that in a year that redefined what games could be, it chose to define itself by what it wasn’t—it was not immersive, it was not innovative, it was not memorable. And in that profound lack of ambition, it perfectly captures the vast, quiet, forgotten majority of software that populated the early information superhighway, going precisely where it was meant to go: nowhere, slowly, with perfect adherence to the rules.