- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Cubiform Games Lab.

- Developer: Cubiform Games Lab.

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Color matching, Item usage, Laser rotation, Puzzle, Reflection

Description

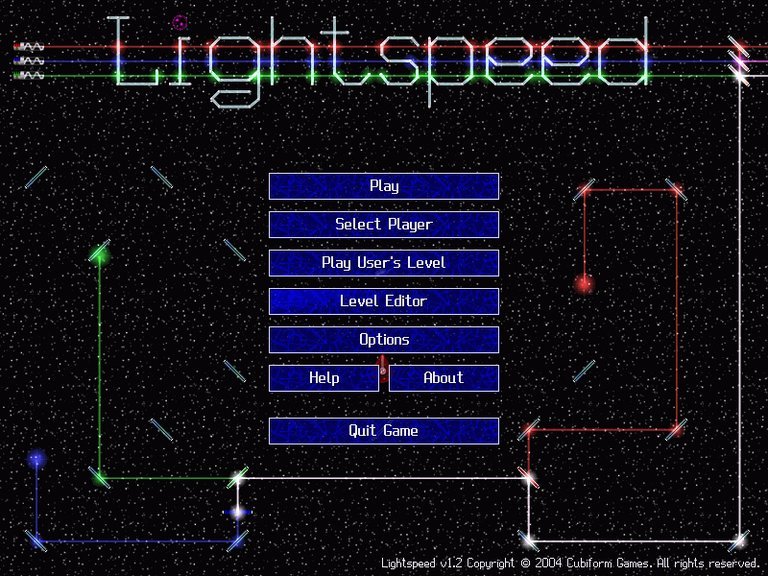

Lightspeed is a top-down puzzle game released in 2003 where players manipulate lasers and optical components to solve intricate light-based challenges. The core objective involves rotating lasers to direct beams toward absorbers with matching colors, utilizing support items like reflectors, color filters, prisms, and multipliers across 52 diverse scenarios. With three difficulty settings and a built-in level editor, the game emphasizes strategic thinking and precision in a minimalist, abstract setting.

Where to Buy Lightspeed

PC

Lightspeed Free Download

PC

Lightspeed Cheats & Codes

PlayStation (PSX)

Enter codes through the Codes menu in the main menu.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| ULTIMATE | Play as Titanium Ranger |

| OMEGA | Level select |

| FOREVER | Infinite continues |

| IMMORTAL | Infinite lives |

| D4B7E1O9G7 | Infinite health |

| N7F6U2A5A1 | Infinite RPE moves |

| SHOWCASE | All galleries |

| 800B3978 0001 | Unlock Level Skip Cheat |

| 800B39CC 0001 | Unlock Continue Modifier Cheat |

| 800B3940 0001 | Unlock Infinite Lives Cheat |

| 800B39E8 0001 | Unlock Infinite RPE Cheat |

| 800B3994 0001 | Unlock Titanium Ranger Cheat |

| 800B39B0 0001 | Unlock Blind Enemies Cheat |

| 800B3A04 0001 | Unlock ??? Cheat Cheat |

| 800B3A20 0001 | Unlock All Galleries |

| 5000081C 0000 | Unlock All Cheats (GS 3.0 or Higher Needed) |

| B008001C 00000000 | Unlock All Cheats (Caetla Users Only) |

| 801575D8 0004 | Infinite Lives (Red Ranger Level 1) |

| 801574FC 00FF | Infinite Health (Red Ranger Level 1) |

| 801575EC 00FF | Infinite Special Meter (Red Ranger Level 1) |

| 801575F8 0010 | Have Special (Red Ranger Level 1) |

| 8015762C 967F | Max Score (Red Ranger Level 1) |

| 8015762E 0098 | Max Score (Red Ranger Level 1) |

| 80157484 0004 | Infinite Lives (Blue Ranger Level 1) |

| 801573A8 00FF | Infinite Health (Blue Ranger Level 1) |

| 80157498 00FF | Infinite Special Meter (Blue Ranger Level 1) |

| 801574A4 0010 | Have Special (Blue Ranger Level 1) |

| 801574D8 967F | Max Score (Blue Ranger Level 1) |

| 801574DA 0098 | Max Score (Blue Ranger Level 1) |

| 80157550 0004 | Infinite Lives (Green Ranger Level 1) |

| 80157474 00FF | Infinite Health (Green Ranger Level 1) |

| 80157564 00FF | Infinite Special Meter (Green Ranger Level 1) |

| 80157570 0010 | Have Special (Green Ranger Level 1) |

| 801575A4 967F | Max Score (Green Ranger Level 1) |

| 801575A6 0098 | Max Score (Green Ranger Level 1) |

Game Boy Color (GBC)

Enter passwords in password screen or use Gameshark device for codes.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| VGBHV3XF | Before mysterious level |

| BVLJCB1C | City 1 complete |

| DVLJWB1C | City 2 complete |

| JVLKWB1C | City 3 complete |

| BLLJCB9D | Dam 1 complete |

| BLLJWC9D | Dam 2 complete |

| VLLJWH9D | Dam 3 complete |

| VGBHV3WJ | Diobolico defeated |

| BLLNCB1D | Plant 1 complete |

| BLL5WB1D | Plant 2 complete |

| VLN5WB1D | Plant 3 complete |

| BLLGCB1L | Plant Rescue Completed Gold |

| BLMDWB1T | Plant Battle Completed Gold |

| VLLFWB1T | Plant Megazord Completed Gold |

| CBLGCB1P | City Rescue Completed Gold |

| GBLGWB1T | City Battle Completed Gold |

| VBLHWB1T | City Megazord Completed Gold |

| BBLGCCDN | Dam Rescue Completed Gold |

| BBLGWDXS | Dam Battle Completed Gold |

| VBLHWBXS | Dam Megazord Completed Gold |

| BBZGCBXM | Bay Rescue Completed Gold |

| BDGGWBXR | Bay Battle Completed Gold |

| VBGHWBXR | Bay Megazord Completed Gold |

| BBGGC3XL | Subway Rescue Completed Gold |

| BBGGZ3XQ | Subway Battle Completed Gold |

| VBGHV3XQ | Subway Megazord Completed Gold |

| VBGHV3WT | All Stages Completed |

| Hold B | Super punch (hold B until color changes, then release) |

| 0132C1C7 | Infinite Time |

| 010CE2C7 | Infinite Life |

| 010AE3C7 | Infinite Energy |

| 0114D9C7 | 20 Hostages Saved Or Batlings Killed |

| 0101DAC7 | Have Break Door |

| 0101DBC7 | Have Put Out Fire |

| 0101DCC7 | Have Cut Cable |

| 0101DDC7 | Have Medicine |

| 0101DEC7 | Have Grappling Hook |

| 0109E9C7 | Infinite Lives |

| 0108E2C7 | Infinite Health |

Lightspeed (2003): A Luminous Deep Dive into Obscurity and Elegant Puzzle Design

As a game historian, I am perpetually fascinated by the vast, uncatalogued graveyard of software—titles that flickered briefly in shareware catalogs or on nascent indie portals before sinking into deserved or undeserved oblivion. Lightspeed (2003), developed and self-published by the enigmatic Cubiform Games Lab., is one such title. It emerges not from a bustling corporate studio but from the quiet, focused efforts of a tiny team (primarily Michael Kulagin and Salavat Valiullin) creating a pure, unadulterated puzzle experience. At first glance, it is easily mistaken for its more famous, entirely unrelated namesake: MicroProse’s 1990 space strategy hybrid, Lightspeed. This review, however, will excavate the 2003 puzzle game, a masterclass in constrained mechanical design that, despite its near-total anonymity, stands as a testament to the power of a single, brilliant core idea. Its legacy is not one of commercial success or critical acclaim, but of pristine, uncompromising puzzle architecture.

Development History & Context: The Quiet Labors of Cubiform

To understand Lightspeed (2003), one must first divorce it from the shadow of its 1990 predecessor. The Lightspeed of MicroProse, designed by Andy Hollis and Sandy Petersen, was a product of the golden age of space sims—an ambitious, real-time 4X title with polygonal graphics that, despite innovation, was critically panned as repetitive and shallow. In stark contrast, Cubiform’s Lightspeed was born in a different era and a different mindset.

Cubiform Games Lab. appears to have been a micro-studio, likely a two-person operation given the credits (Kulagin: Programming, Sound, Additional Graphics; Valiullin: Design, Graphics). The game was released on November 30, 2003, for Windows as shareware—a distribution model then in its twilight, clinging to life before the dominance of Steam and digital storefronts. This was the era of self-hosted websites, downloadable ZIP files, and listings on aggregate sites like MobyGames. There was no marketing budget, no publisher hype, just a game uploaded to the internet with a hope.

Technologically, it was a creature of its time: a top-down, fixed/flip-screen puzzle game built for a mouse-driven, point-and-select interface. It required no more than a standard Windows PC of the early 2000s. The constraints were not of hardware but of scope and vision. The team’s goal was not to simulate a galaxy but to perfect a single, interacting system of light and matter. This focus is evident in the credits: there are no writers, no mission designers, no sound composers beyond Kulagin’s functional effects. Every ounce of development energy went into the logic of the puzzle mechanics and the construction of 52 scenarios.

The gaming landscape of 2003 was dominated by 3D epics (KOTOR, Prince of Persia: Sands of Time), online multiplayer surges (Call of Duty, Xbox Live), and the maturation of indie games like Blast Corps or Psychonauts (though those were publisher-backed). Lightspeed existed on the fringe, in the same conceptual space as experimental browser games or academic logic puzzles. Its context is one of quiet, deliberate craft, battling for attention in a market moving too fast for such a niche, contemplative title.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story of Pure Logic

Lightspeed (2003) possesses no traditional narrative. There is no plot, no characters, no dialogue, no setting lore. The player is presented with a clean, abstract grid and a series of objectives. This absence is not a failing but a thematic and philosophical statement. The game’s “story” is the progressive unfolding of a complex logical system.

The narrative is implied through the taxonomy of puzzles (scenarios) and the behavior of its constituent elements. The language used to describe the game’s components is itself a narrative of physics: lasers emit beams, absorbers consume light of a specific color, reflectors bend paths, prisms decompose white light into its basic colors. The player’s journey is one from simple cause-and-effect (rotate laser to hit absorber) to mastering a chromatic and spatial algebra.

The core theme is control and transformation. The player is a silent engineer, a light-bender, manipulating fundamental properties—direction, color, transmission—to achieve harmony (all absorbers illuminated). The tools introduce deep thematic concepts:

* Decomposition & Synthesis: The Prism breaks white light into red, green, and blue. The Generator of the white reverses this, requiring the recombination of primary colors. This mirrors fundamental optical physics.

* Filtering & Permeability: The Color Filter is absolutist; only the correct color passes. The Semitransparent Reflector allows a beam to both reflect and continue, introducing the concept of superposition and resource sharing.

* Multiplication & Energy: The Multiplier creates parallel beams from one, a direct manipulation of energy output.

* Transmutation: The Transformer changes a beam’s color, representing a mutable state in a closed system.

* Thermodynamics (Abstracted): The Shifter “cools down or warms up” colored beams—an intriguing, almost poetic mechanic that adds a layer of non-intuitive state change, suggesting hidden properties of the light itself.

The ultimate narrative challenge is the player’s own cognitive progression. Scenario 1 teaches rotation. Scenario 10 introduces a prism. Scenario 30 might require a fixed laser, a shifter, two multipliers, and a semitransparent reflector with a color filter, all working in concert to create a precise chromatic cocktail for three absorbers. The story is the player’s dawning comprehension, the “aha!” moment when the system’s rules click into a mental model. It is a narrative of pure intellect, where the protagonist is the solver and the antagonist is the puzzle’s initial state.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Luminous Engine

This is where Lightspeed achieves its brilliance. The core gameplay loop is singular and hypnotic:

1. Assessment: Observe the grid. Identify laser(s), their initial orientation and color (white or a primary color: red, green, blue). Identify absorber(s) and their required color(s). Identify any fixed elements or pre-placed support items.

2. Planning: Mentally trace potential beam paths. Consider color needs. Decide which support items to place/rotate and in what order/configuration.

3. Execution: Use the mouse to click on a laser or item and rotate it (usually in 90-degree increments). Place additional items (reflectors, filters, etc.) from a toolbar onto empty grid spaces.

4. Verification: Watch the simulated beam(s) propagate. Do they hit all absorbers? Is the color correct for each? (A red absorber must be hit by a red beam, or a mix that yields red? The description implies direct color matching, but complex setups might involve white light decomposition).

5. Iteration: If unsuccessful, undo moves or reset, and try a new hypothesis.

The innovation lies in the interaction of its ten support items, which form a complete, interdependent toolkit:

- Reflector: The fundamental mirror. Changes beam direction by 90°. A building block.

- Semitransparent Reflector: A philosophical upgrade. The beam reflects and continues straight. Enables splitting a beam’s path without a multiplier.

- Color Filter: A gate. Only a beam of the exact matching color passes; other colors are blocked. This is crucial for directing specific colors to specific absorbers from a shared beam path.

- Semitransparent Reflector with Color Filter: A compound device. It reflects the matching color beam and allows that same matching color to continue. Non-matching colors are blocked entirely. Incredibly powerful for routing.

- Multiplier: Creates n identical beams from one input. Essential for powering multiple absorbers from a single source, but increases system complexity.

- Prism: A decomposer. Inputs a white beam and outputs three separate red, green, and blue beams at 90° angles (typically). The inverse of a generator.

- Generator of the White: A recomposer. Requires red, green, and blue beams to strike it simultaneously (or in sequence?) to emit a single white beam. Solves the problem of creating white light from colored components.

- Shifter: The most enigmatic. “Will either cool down or warm up colored beams.” This suggests a hidden temperature state for each color beam. A “warm” red might be different from a “cool” red, and only one state can pass a given absorber or interact with another shifter. It adds a second, orthogonal layer of logic beyond simple color routing. This is the game’s deepest, most cryptic mechanic.

- Transformer: A color converter. It changes the color of the initial beam (presumably the beam entering it) into the color it is currently “set to.” This allows the player to dynamically recolor a beam stream to match downstream needs.

The scenario design leverages these tools with pedagogical precision. The 52 scenarios are a curated curriculum. The three difficulty settings likely adjust the number of items, lasers, absorbers, or introduce the more complex items (Shifter, Transformer) earlier. The inclusion of a level editor is the game’s masterstroke. It transforms the player from a consumer into a creator, allowing them to design their own chromatic-conundrums and share them, theoretically extending the game’s life indefinitely. This feature alone elevates it from a puzzle collection to a puzzle system.

The interface is beautifully minimal: a top-down view, clear laser beam visualization (differentiated by color and maybe style for white vs. colored), and a clean toolbar. The “Fixed / flip-screen” perspective means the player sees the entire puzzle grid at once, encouraging holistic thinking rather than scrolling. There are no extraneous stats, no resource management beyond the puzzle itself. It is a pure logic toy.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Minimalist Aesthetics for Maximal Focus

Lightspeed (2003) embraces abstraction as its aesthetic philosophy. There is no “world” in a narrative sense. The “setting” is a liminal, grid-based void—a conceptual space where the laws of physics are simplified and instrumented.

Visual Direction: The graphics are functional and clear. The perspective is top-down. Lasers are simple lines or thin rectangles. Absorbers are distinct shapes or icons that visually “activate” (maybe glow or change color) when hit. Support items have easily identifiable icons (a mirror for Reflector, a prism shape for Prism, etc.). The color palette is restrained and logical: bold, distinct primary colors (red, green, blue) and white/black for contrast. There is no attempt at realism or “juice” (screen shake, particle explosions). The beauty is in the clarity of information—a beam’s path must be instantly legible against the grid. This is art in service of cognition. The “fixed/flip-screen” nature suggests discrete, self-contained chambers, reinforcing the puzzle-box feel.

Sound Design: Michael Kulagin’s sound effects are utilitarian and effective. We can infer (from the lack of description and the era) sounds for: laser activation, beam reflection, item placement, and a satisfying chime or hum when an absorber is successfully activated. There is likely no music, or perhaps subtle, ambient loops to avoid distraction. The soundscape exists to auditoryize the state changes—the moment a beam connects with an absorber is probably punctuated by a crisp, positive feedback sound. In a game of silent concentration, these audio cues are vital punctuation marks.

Together, the art and sound create an atmosphere of calm, focused laboratory work. It is the aesthetic of a clean whiteboard, of a well-organized toolbox. This minimalism prevents sensory overload, allowing the player’s entire mental bandwidth to be consumed by the spatial and chromatic logic.

Reception & Legacy: The Quiet Triumph of the Niche

By any conventional metric, Lightspeed (2003) is a commercial and critical ghost.

* Commercial: As a shareware title from an unknown studio, its sales were infinitesimal. It had no retail presence. Its “collection” numbers on MobyGames (4 players) are a testament to its obscurity.

* Critical: There are zero critic reviews listed on MobyGames. No mentions in mainstream gaming magazines of the era. Its player rating is 4.1/5 from 2 ratings—a tiny sample size suggesting a minuscule but pleased audience.

* Contrast with the 1990 Lightspeed: This is where historical context gets poignant. The MicroProse Lightspeed (1990) was a high-profile flop, mocked by Computer Gaming World as “more repetitive than ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas'” and listed among the “50 Worst Games of All Time.” Cubiform’s Lightspeed, a far superior piece of design in its own domain, is utterly forgotten while its namesake is remembered with scorn. This highlights the cruel lottery of game preservation: fame, even infame, requires a platform.

Its legacy is therefore subterranean and direct. It belongs to the lineage of light-and-mirror puzzles, a subgenre with roots in Larn (1986) and Dungeon Master‘s optical puzzles, and more recently seen in games like The Witness (2016) and Baba Is You (2019) in their laser-based segments. Its specific contribution is the chromatic layer and the richness of its toolset (especially the Shifter and the compound semitransparent items). The level editor is its most significant legacy feature, as it allows the community—however small—to perpetuate the game’s logic engine indefinitely.

Its influence is likely not on AAA titles but on puzzle enthusiasts, academic game design studies, and the tiny ecosystem of shareware-era logic games. It is a game that would be cited in a paper on “mechanics-first design” or “constraint-based puzzle generation.” It represents a pure, unscalable ideal: a game built for the sheer joy of solving an elegant system, with zero concessions to mass appeal.

Conclusion: A Precise Beam in the Dark

Lightspeed (2003) by Cubiform Games Lab. is not a great game in the sense of being widely influential, commercially successful, or historically pivotal. It is, however, a flawlessly executed specimen of a very specific type. It takes the elegant, innate fun of directing a light beam and builds an entire, profound puzzle language around it. Its mechanics are introduced, explored, and combined with a designer’s precision. The absence of narrative, of avatar, of skin, is its greatest strength—it is pure, unadulterated ludonarrative.

Its flaws are those of its ambition and its era. The Shifter mechanic, while brilliant, is poorly explained in-game (the source material gives no clarity on “cool/warm” states), potentially creating obtuse roadblocks. The art and sound are barebones, which may alienate players weaned on “juicy” modern indies. Its obscurity is almost total, a victim of being ahead of the indie curve but behind the digital distribution one.

In the grand hall of video game history, Lightspeed (2003) has no statue. It does not deserve one. Instead, it deserves a small, well-lit vitrine—not for its fame, but for its purity. It is a game for the connoisseur, the logician, the player who finds joy in a perfectly balanced equation. It is the laser beam that hit its absorber with absolute precision, a quiet, glowing testament to the idea that a game, stripped to its essential interactive core, can still illuminate the mind. Its verdict is not a score, but an observation: it is a near-perfect realization of a narrow vision, and in that narrowness, it finds its timeless, if microscopic, place.