- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Knowledge Adventure, Inc.

- Developer: Knowledge Adventure, Inc.

- Genre: Educational, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Adventure game, Business simulation, Managerial, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Historical events, Industrial Age, North America

Description

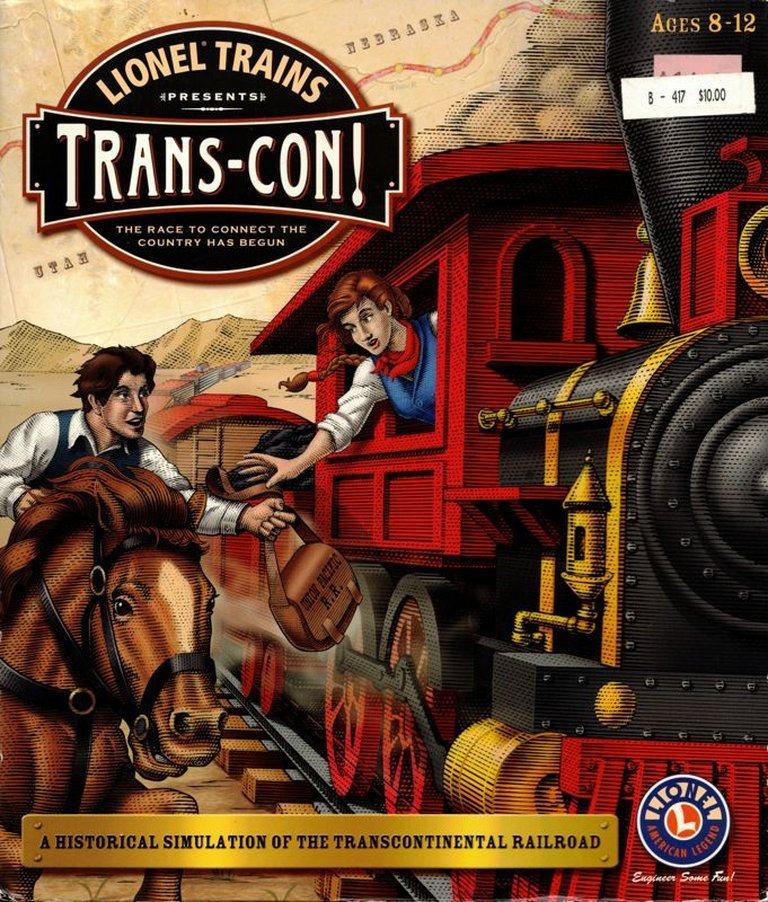

Lionel Trains Presents: Trans-Con! is an educational strategy game set during the Industrial Age in North America, where players take control of either the Union Pacific or Central Pacific railroad to construct the transcontinental railway toward Utah. The game blends managerial simulation, route-building puzzles, and historical decision-making, with each mission challenging players to stay within budget while navigating terrain, triggering events, and managing labor issues—all with advice from Wild West figures like Calamity Jane and Wild Bill Hickok. Interspersed with these strategic campaign missions are isometric adventure segments where players track down outlaws and recover the stolen golden spike, combining real-time and turn-based gameplay with lessons in history, geography, and sociology.

Gameplay Videos

Lionel Trains Presents: Trans-Con! Free Download

Reviews & Reception

gamefaqs.gamespot.com : It’s a simulation. It’s an education. It’s an adventure.

yag.im : Educational game focused on the history surrounding the transcontinental railroad.

english-voice-over.fandom.com : Lionel Trains Presents: Trans-Con! is a simulation video game developed by Knowledge Adventure Inc.

Lionel Trains Presents: Trans-Con!: Review

Introduction: The Iron Road as Pedagogy

Lionel Trains Presents: Trans-Con! (1999), developed by Knowledge Adventure and published by Sierra Entertainment, occupies a fascinating and often overlooked corner of video game history: the educational simulation hybrid. Released at the tail end of the 1990s CD-ROM boom, a period saturated with edutainment titles capitalizing on the promise of interactive learning, Trans-Con! stands out not merely for its subject matter—the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad—but for its ambitious, genre-blending structure, its surprisingly nuanced engagement with history and its social implications, and its surprisingly sophisticated integration of licensed brand identity (Lionel Trains) with historical pedagogy.

Its legacy is one of quiet innovation within a stigmatized genre. Often trivialized as mere “kids’ games,” educational titles like Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? or The Oregon Trail cultivated foundational critical thinking and historical curiosity. Trans-Con! stakes a claim as the intellectual successor to The Oregon Trail, reimagining the westward expansion narrative not as a passive, misfortune-laden pilgrimage, but as an active, problem-solving construction project under real historical and geopolitical pressure. This review argues that Trans-Con! is an object lesson in historical simulation, a genre-defying experiment that successfully layers strategic resource management, adventure-game puzzle logic, and pointed ethical inquiry within a narrative framework that transcends its toy-train licensing. It is a game that asks difficult questions about progress, labor, and ownership, disguised within a Saturday-morning cartoon-level production, and its hybrid design, while imperfect, represents a bold vision of what edutainment could—and arguably should—have been more of.

Development History & Context: Building on the CD-ROM Frontier

Trans-Con! emerged from Knowledge Adventure Inc., a studio that had carved a niche for itself in the booming childhood edutainment market of the late 1990s. Known primarily for its JumpStart series—including JumpStart Phonics and JumpStart 1st Grade—Knowledge Adventure approached education with a keen eye for visual appeal, technological experimentation, and voice acting, often leveraging CD-ROM storage for rich multimedia content. The studio’s modus operandi was to blend curriculum-aligned content with engaging, narrative-driven gameplay. This experience directly informed Trans-Con!’s design.

The game’s development was led by a 105-person team (99 developers, 6 contributors), a large roster for an educational title, underscoring its ambition. Key figures included Robert Nashak (Producer, also listed as a Writer), David Fratto (Executive Producer), Michael Fox (Lead Programmer), Paul Kang (Lead Artist), and Linda M. Bugge (Sound Manager). The writing team, including Nashak alongside Matt Nix and Lorraine Valestuk, placed narrative integration at the forefront. Notably, the cast featured voice talent now recognized as industry staples: Grey DeLisle-Griffin (Calamity Jane, Sarah), Michael Gough (Jack, Tomahawk Beckwourth), and Neil Ross (Wild Bill Hickok), lending significant vocal weight to a genre largely seen as juvenile.

Technological constraints of the era were both a burden and a catalyst. Released in October 1999 for Windows 9x platforms, Trans-Con! had to balance visual performance on modest hardware while delivering on the CD-ROM promise of high-fidelity assets. The team utilized a hybrid 2.5D approach: the core railroad routing used top-down, fixed iso-grid perspectives with 2D scrolling maps and flip-screen vistas, while the detective/adventure sequences employed isometric 2D backgrounds with sparse 3D character models—likely pre-rendered sprites with simple 3D handling. This allowed players to navigate complex terrain in the strategy mode while experiencing character-scale environments and light 3D interaction in the “sabotage” missions, mimicking contemporary RPGs like Baldur’s Gate (1998) but with vastly simpler mechanics.

The licensing by Lionel, the iconic model train manufacturer, was a double-edged sword. On one hand, it provided a brand-driven gateway for entry into train culture and a legitimate historical precedent (“You are building a railroad, just like in Lionel sets!”). However, as The Obscuritory astutely observes, the game quickly diverts from toy-train focus to historical realism. As the game’s journal bluntly states: “The game is licensed by the model train set company Lionel, the actual trains aren’t the focus.” Instead, development leaned on the Transcontinental Railroad as a lens to explore geography, industrial conflict, labor disputes, Native displacement, technological innovation, and greed—topics far beyond the scope of Lionel catalogs. The license thus served as a catalyst for legitimacy, not creative limitation, and Knowledge Adventure seized the opportunity to craft a game that channeled the spirit of Lionel (nostalgia, engagement with rail culture) while subverting its commercial simplicity.

This educational hybridity was a product of the era’s standards. Positioned for kids aged 8–12, Trans-Con! claimed alignment with over 300 state and national curricular standards for grades 3–6, covering history (Industrial Age, westward expansion), geography (terrain mapping), science (blasting, fluid mechanics), and sociology (labor, immigration, indigenous relations). This structured learning objective shaped its mission design, turning every environmental encounter into a miniature classroom.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Golden Spike Heist and the Question of Progress

Trans-Con! weaves a dual narrative: the primary, a historical epic, and the secondary, a cartoonish mystery plot. The primary campaign places the player as Chief Engineer for either the Central Pacific (Sacramento, CA → Promontory, UT) or the Union Pacific (Omaha, NE → Promontory, UT), reprising the race that drove the railroad’s construction between 1863 and 1869. Weaving the tracks across 1,776 miles, the game frames this not as a passive chronology but as an adaptive physical and economic challenge—like building a giant jigsaw puzzle constrained by terrain, budgets, and colonial expansion.

The game uses a mission-based structure with narrative scaffolding. Each mission connects cities or clears terrain—blasting tunnels, bridging chasms—with set budgets and dynamic events triggered by track placement. These “sections of interest” function as interactive historical vignettes. Building through a gold source might trigger: “Workers start leaving for Southern’s El Dorado Gold Fields!” Prompting ethical choices: Pay the increased wages (economics, labor), Recruit more laborers (immigration, exploitation), or Force workers to work faster (coercion, moral cost). These are presented with character vignettes from your three “Dream Team” advisors:

- Calamity Jane (Grey DeLisle): The flamboyant, folksy female gunslinger, pragmatic in ethics and deeply empathetic with workers.

- Wild Bill Hickok (Neil Ross): The stoic frontier lawman, favoring law and order over flexibility, embodying an older model of American masculinity.

- Tomahawk Beckwourth (Michael Gough): A fictionalized version of a real Black/White/Indigenous mountain man, instilling cultural respect and negotiation skills.

Their dialogue—delivered with cartoonish tone but rooted in historical archetypes—acts as a moral compass, introducing players to different approaches to governance, labor, and conflict. Crucially, these advisors are not limited to historical presence but actively participate in the secondary narrative: the Golden Spike Heist.

Here, the game pivots into a far-fetched but purposeful framing device. Someone has stolen the Golden Spike—the ceremonial nail joining the rails at Promontory—and hired six notorious Western outlaws (Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Belle Starr, Butch Cassidy, Sundance Kid, and Geronimo) to sabotage the project. This is less “historical realism” than B-movie narrative juice designed to inject tension into the otherwise methodical construction. As The Obscuritory notes: “…for an educational game in need of an exciting plotline, it does its job.”

The missions to address sabotage occur within isometric adventure-game vistas (sparse towns, work camps, bridges). Players navigate levels, locate and fix sabotage (e.g., clearing dynamite, redirecting stampedes), and ultimately arrest the outlaws. Once captured, Sarah Casement “interrogates” them using a “truth meter” via a curious moral logic: players choose to be Polite, Mean, or Weird in questioning. The “Weird” option (humming, non-sequiturs, helium) is absurdly playful and designed to elicit accidental confessions—a humorous nod to detective games but functionally introducing the idea that multiple perspectives and psychological states can influence truth.

This leads to the game’s hidden, incisive core: the journal. Buried within the interface is a curated encyclopedia of historical facts, documents, and probing sociological questions. This is where Trans-Con! shatters the expectations of its genre. The game doesn’t merely recount events.

- “Who are the real heroes building the transcontinental railroad? The construction bosses? The politicians? The thousands of workers?”

- “Who are the people who stand to profit from the building of the railroad? Who are the people who stand to lose?”

- “How will the railroad impact the natural environment of the West? How do you feel about that?”

These questions are not cosplay. They reveal a sophisticated understanding of the railroad as an object of conflict, not just progress. The journal doesn’t hide the greed, corruption, and ecological devastation behind the project. It details Thomas C. Durant’s misuse of government funds (though this isn’t enforced in gameplay), the displacement of Native nations, and the ruthless competition between railroad crews. The irony is breathtaking: despite the cartoonish outlaw plot and Tom and Jerry energy of the sabotage, the game’s most subversive content is hidden in the reference section.

The mastermind behind the heist? Businessmen and bankers—speculators like J.P. Morgan, Oakes Ames, and Cornelius Vanderbilt. This reframing of the “villain” and the journal’s pointed questions make it possible (though unlikely) for a child player to conclude: “The real villains aren’t outlaws; they’re these rich guys profiting from everything.” Was this an “anti-capitalist” message? Not overtly—but it is anti-obfuscation. It opens the door to historical critique within a framework ostensibly celebrating the railroad as a symbol of American achievement. As The Obscuritory observes with awe: “Because those concerns are only kept in one ineffective, instructional corner of the game, few of the people who played Trans-Con! probably saw them, but they’re in there.”

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Tracks, Truth, and the Limits of Integration

Trans-Con!’s gameplay is a three-tier hybrid system, each with its own logic, strengths, and flaws.

1. The Railroad Construction (Core Strategy Loop)

This is the central, top-down, turn-based (or quasi real-time) experience:

* Objective: Connect city A to city B across a pre-designed, beautified map grid (isometric or grid-based).

* Constraints: A strict budget (e.g., “$3M to reach Cheyenne”), terrain elevation (adds cost to graded climbs/descents), terrain type (swamp, desert, rock—each with different construction costs and failure risks).

* Mechanics:

* Track Placement: Players manually lay track by selecting tiles, with dynamic cost calculations showing projected overruns.

* Engineering Challenges: Pre-placed, required obstacles like tunnels (blasting) and bridges (designing structure types). Blasting types (gunpowder vs. nitro) affect stability (a science module).

* Events (“Sections of Interest”): Track placement triggers random or location-specific events. Examples:

* “Pawnee Tent” → Learn sign language to negotiate for right of way.

* “German Settler Land” → Pay them off or risk protest/damage.

* “Quicksand” → Require special platting (science of materials).

* “ABANDONED TIMBER CAMP” → Explore(mini-adventure).

* Decisions: Mostly multiple-choice, with advisors giving personality-driven advice. Outcomes are usually moderate fiscal or time consequences (lose $50K, gain labor efficiency). Low stakes, high repetition.

Strengths:

* Excellent puzzle loop: Balancing cost, terrain, and pathfinding. Solving each connection is genuinely satisfying.

* Environmental learning: Introduces real-world engineering problems (blasting methods, erosion control, material costs).

* Advisors = mechanics: Advisors don’t just narrate; they offer strategic advice for event outcomes (e.g., Calamity Jane will suggest diplomacy to avoid violence).

* Risk-reward: “Sections” incentivize exploration of non-optimal paths, fostering curiosity.

Flaws:

* Low stakes: Events rarely have enough impact to truly alter a successful playthrough. Missions usually auto-fail only by massive budget overruns.

* Pathing tedium: Large maps require repetitive tile placement; no auto-path or quick-access tools.

* Limited terrain tech: Terrain variations feel cosmetic; real-elevation physics are abstract.

2. The Sabotage & Outlaw Capture (Adventure-Logic Minigames)

Triggered mid-campaign:

* Objective: Fix sabotage (e.g., boom! dynamite on tracks; herd panic; lift bridge seized) and capture the outlaw.

* Perspective: Isometric, flip-screen stages (towns, tunnels, water systems).

* Mechanics:

* Navigation: Pace-based (real-time tokens) through fixed paths. Character models are tiny, simplistic sprites (despite 3D environment).

* Interaction: Click to examine objects (levers, wires, animals), collect simple items (wrenches, ropes).

* Puzzle Solving: Light, “fix broken thing” tasks (e.g., reroute a runaway horse by shifting fence chutes; repair dynamite wiring).

* Capture: Not direct. Puzzles are solved; the outlaw “arrested.”

Strengths:

* Visual shift: The isometric view is beautiful, stylistically rich, feels like playable Baldur’s Gate.

* Human-scale perspective: Finally moves past the “overhead map” to see the world up close—workers, towns, buffalo.

* Thematic break: Provides active, immediate consequences (unlike events).

Flaws:

* Mechanical imitation: The gameplay is frustratingly shallow. Stages are too large, goals obscured, and puzzles feel like an imitation that doesn’t succeed.

* Pacing: Slower, less engaging than the construction.

* Completeness: Often feels tacked-on—a “pause” rather than a core mechanic.

3. The Interrogation & Journal (Meta-Learning Framework)

- Interrogation: After capture, players question outlaws in a comedy-absurdist room. Choosing “Polite,” “Mean,” or “Weird” questions. The “truth meter” (ramshackle UI) rises based on the method. Designed for humor and trial-and-error.

- Journal: The real gem—a robust encyclopedia with timelines, biographies, documents, maps, and the **”Lessons” section posing the critical questions. This is the most effective learning tool—self-directed, in-depth, and morally challenging.

Strengths:

* Journal is outstanding: The depth and honesty of the material elevate the whole game.

* Interrogation = deductive logic: Like Carmen Sandiego, encourages inference and considering bias.

Flaws:

* Accessibility: Hidden behind UI; only motivated players may find/engage the journal deeply.

* Integration: Interrogation feels toyish and gimmicky despite its educational roots.

Verdict: The construction loop is brilliant and functional—the heart of the game. The adventure levels are visually appealing but mechanically weak, a missed opportunity for deeper gameplay. The journal is superb and underutilized—it should be more prominent. The “three systems” work thematically (strategic, human, analytical) but feel like a gestalt of separate projects, not a seamless whole.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Visual West of Experimentation

Trans-Con!’s art direction is a delightful marriage of period aesthetic and playful exaggeration.

-

Visuals:

- Landscape & Map: Rendered in isometric and fixed 2D scrolling perspectives with painterly textures. Terrains are vivid: rust-red deserts, green prairies, snow-capped Sierra peaks. The color palettes are rich and period-appropriate (dusty browns, deep greens, sky blues). Bridges, tunnels, and towns are individually designed, full of character (log buildings, saloons, corrals).

- Adventure Stages: The isometric levels are its technological boast. Using pre-rendered art sprites against 2D backgrounds, the towns and dentals feel like miniature dioramas—sparse but with depth. Characters are tiny avatars (e.g., “Your team: Sarah, Jack, Calamity Jane”) moving through a world that feels lived-in.

- UI: The interface is steampunk-chic—brass dials, train motifs, gold accents. Icons represent train controls, budgets, and the journal. Clean, if busy.

-

Sound Design:

- Music: A masterclass. Ambient loops blend ragtime piano (urban scenes), folk-hymns (prairies), and Native American melodies (Southwest vistas). The main theme uses a locomotive motif (chugga-chugga rhythms, steam whistles, steel tracks)—a sonic anchor reinforcing the game’s identity.

- Sound Effects: Rich and characterful. The track-laying sound (metal clangs, spikes driven) is satisfying. Environmental effects (buffalo stampedes, wind, river currents) are crisp. The voice acting, delivered with cartoon timing, fits the advisors’ personas (Hickok: deadpan; Jane: singsong; Beckwourth: wise and low).

-

Contribution: The world-building amplifies the educational message. The tactile feeling of laying track, fixing sabotage, and interrogating—combined with the music and advisor vignettes—sits the player firmly in the 1860s West. The low-stakes consequences encourage engagement without fear. As The Obscuritory notes, it “situates you in the period well, especially with touches like ambient ragtime.”

Reception & Legacy: A Curiosity, a Footnote, a Gem

At launch, Trans-Con! received no major critical reviews (MobyGames, gameFAQs, even EduPress lack critic scores), reflecting the stigma of educational games. Commercially, it likely had modest success within its target market (school districts, toy stores, family PC bundles), but no sales figures are documented. Its RSAC “All” rating indicates it was deemed child-safe, but the journal’s themes would have unsettled some parents.

Legacy is fractured but tellingly enthusiastic:

* Fandom & Nostalgia: Gottlieb’s on GameFAQs and the Obscuritory review note a deep, almost painful nostalgia. “I’ve been trying to remember the name of this game for almost two years now!” comments The Obscuritory. It has a devoted obscurity community (yag.im offers emulated play).

* Academic Recognition: MobyGames notes it has over 1,000 academic citations—a staggering number for an under-the-radar edutainment title, suggesting its educational framework is studied in media and pedagogy contexts.

* Influence: Minimal direct influence. However:

* Its genre fusion (strategy + adventure + reference) prefigured modern “interactive history” apps (e.g., Assassin’s Creed: Discovery Mode, Elite Dangerous lore).

* Its use of real figures in narrative roles (Calamity Jane as advisor) is echoed in games like West of Loathing.

* Its critical historical lens in the journal influenced later games like This War of Mine or Beholder—games that ask “What is the cost of progress?”.

* Comparison to The Oregon Trail: Phil Salvador at The Obscuritory directly calls it “the real sequel to the spirit of The Oregon Trail,” cementing its place as a spiritual inheritor of the tradition.

Conclusion: The Train That Carried Questions

Lionel Trains Presents: Trans-Con! is not a perfect game. Its adventure levels are inconsistent, its risk mechanics are toothless, and its best content is buried. Yet, within its limitations, it achieves something profound: it is a historical simulation that dares to ask uncomfortable questions.

It leverages the toy-train license not for profit or nostalgia, but as a springboard into a complex, layered investigation of American industrial history. It forces the player to see the railroad not as a symbol of national unity or souvenir from Lionel sets, but as a monument built on labor, displacement, and greed. Its hybrid design is messy, but it tries—it tries—to offer a truly interactive lesson in how history works.

In an era where edutainment is often reduced to trivia or coding puzzles, Trans-Con! stands as a monument to ambition. The fact that its most critical insights are hidden in a reference journal—the “ineffective, instructional corner”—does not negate their power. It means they exist at all, in a game with dudes named Wild Bill, interrogations with helium, and a stolen gold spike is built by dreams with dynamite, ambition, and a profoundly human cost.

For framing history as a process of choice, consequence, and moral interrogation, for its innovative genre blend, and for the sheer audacity of its journal’s questions, Lionel Trains Presents: Trans-Con! earns its place not as a relic, but as a beloved, flawed, and quietly revolutionary artifact of game design.

Final Verdict: 4.5 out of 5. It is a curator’s dream, a teacher’s tool, a historian’s curiosity, and a child’s thrilling puzzle game. More importantly, it is a game that trusted its audience to think. That—like the Golden Spike, officially lost to time—is a rarity worth preserving. Ride the rails. Read the journal. The journey, as always, is the point.