- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Inventory management, Point-and-click, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Basement

Description

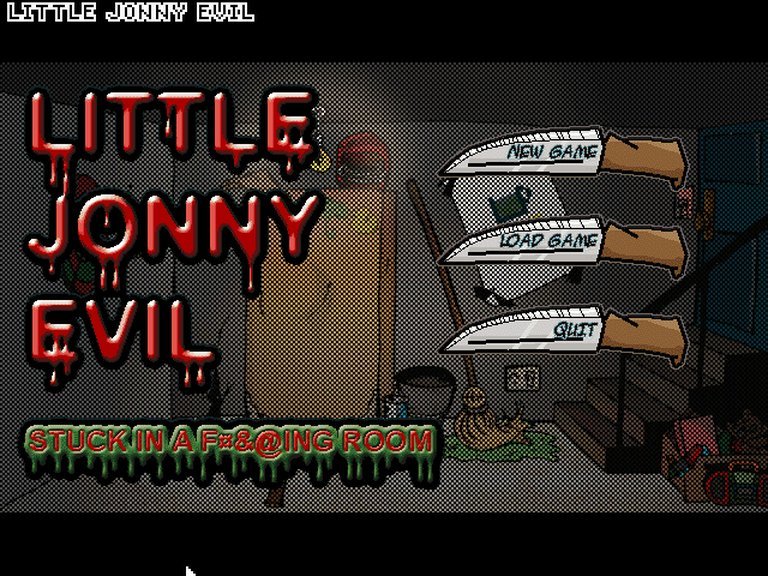

Little Jonny Evil is a short, free 2D point-and-click adventure game developed with Adventure Game Studio. Players control Jonny, a psychopathic child locked in a single basement room by his mother, and must use puzzle-solving and inventory management to find a way out through the only door.

Little Jonny Evil Free Download

Little Jonny Evil Guides & Walkthroughs

Little Jonny Evil Reviews & Reception

adventuregamestudio.co.uk : This was a fun little game.

Little Jonny Evil: A Microcosm of Malevolence – A Definitive Historical Review

1. Introduction: The Devil in the Detail (or the Basement)

In the vast, sprawling history of video games, certain titles achieve prominence through scale, technical prowess, or cultural saturation. Others, however, secure their place not by dominating the landscape but by embodying a potent, concentrated idea so perfectly that they become cult touchstones. Little Jonny Evil is unequivocally one of the latter. Released on August 10, 2002, this free, 862KB point-and-click adventure is not merely a game; it is a narrative and mechanical haiku, a compact burst of subversive design that punches far, far above its weight. Its legacy is not measured in sales but in the lingering, unsettling smile it leaves on the player’s face. This review argues that Little Jonny Evil is a seminal piece of indie game design from the early Adventure Game Studio (AGS) era—a brilliantly minimalist, tonally audacious puzzle box that uses its extreme constraints to deliver a uniquely potent and darkly humorous experience, forever cementing its status as a fascinating “what if” and a masterclass in focused storytelling.

2. Development History & Context: The AGS Underground

The Studio & The Creator: Little Jonny Evil was developed by “Das KANDYMAN,” a pseudonym for a creator who, like many in the early AGS community, remains an enigma. This was the golden age of the AGS engine, a time when a passionate individual could, with sufficient skill and a free toolset, create a professional-quality adventure game. The community was a vibrant, forum-driven ecosystem of hobbyists pushing the engine’s limits. KANDYMAN’s work, including a demo for Kinky Island, placed them within this creative milieu, but Little Jonny Evil distinguished itself through its singular, uncompromising vision.

Technological Constraints & Creative Flourish: The game’s specs are a testament to its era and ethos: 640×400 resolution, 8-bit (256 colour) graphics, a tiny 862KB footprint. These were not limitations imposed by a lack of ambition, but a framework within which artistry was forced to be economical. Every sprite, every background tile, every sound byte had to earn its place. This constraint bred ingenuity. The “one room” design was likely a practical decision—easier to art, script, and test—but it morphed into the game’s core philosophical and mechanical statement. In 2002, with 3D acceleration becoming standard, choosing to make a tight, polished 2D adventure was itself a quiet act of rebellion.

The Gaming Landscape of 2002: The adventure genre was in a precarious state. The golden age of Sierra and LucasArts had faded, and major publishers were skeptical. The indies and enthusiasts, empowered by tools like AGS, were its true custodians. Against a backdrop of The Longest Journey sequels and Syberia, Little Jonny Evil was an antithesis: no epic journey, no linear narrative, just a boy, a basement, and a will to escape. It existed in the same breath as other concise, brilliant AGS titles like Ben Jordan: Paranormal Investigator and The Mysterious Case of Doctor Arduous, contributing to a movement that kept the classic adventure spirit alive through sheer creativity.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Psychopath’s Lament

Plot Deconstruction: The plot is infinitesimally thin on paper: “Little Jonny has been sent to his room by his mom for making a habit of playing with dangerous toys… now he needs to get out.” This synopsis, from the AGS page, is a masterclass in understatement. The premise is a classic escape room scenario, but the protagonist’s identity transforms it utterly. Jonny is not a wronged hero, a curious child, or a lost explorer. He is, explicitly, a “little psychopathic child” (per the AGS wiki) with a “habit of playing with dangerous toys.” The mother’s punishment is not an injustice to be righted; it is a containment protocol for a nascent force of chaos.

Character: Jonny as Anti-Hero: Jonny is the game’s entire reason for being. His nomination for “Best Player Character in an AGS Game” in 2002 is profoundly telling. He is the rare adventure protagonist who is not a cipher for the player’s morality. His commentary, his chosen methods, and his inevitable success frame the player not as a savior, but as an accomplice. The experience is a collaborative act of mischief. This was a radical notion for a genre populated by do-gooders like Gabriel Knight or Guybrush Threepwood. Jonny’s malevolence is not cartoonish (think Dexter’s Laboratory); it’s pragmatic, cold, and results-oriented. You don’t play as Jonny; you play with him, enabling his escape from a just imprisonment.

Themes: Authority, Play, and Subversion: The game is a dense thematic study in miniature.

* The Failure of Authority: The mother is an unseen, absolute authority figure whose only acts are punishment and (implied) obliviousness to the severity of her son’s nature. The basement is her cell, but it becomes his workshop. The game argues that true malevolence cannot be contained by simple bars and locks.

* Play as Destruction: Jonny’s “dangerous toys” are not action figures but mechanisms of mayhem. His play is not imaginative but destructive. The puzzle-solving is an extension of this—the world is a lock, and Jonny must find the tool (or combination of tools) to dismantle it. The act of escaping is the ultimate “play” with the system that seeks to restrict him.

* Complicity and the Player: The most powerful theme is the player’s complicity. There is no moral choice; the goal is singular. The unsettling humor arises from this alignment with a clear “villain.” It asks: what happens when an adventure game’s hero is fundamentally unsympathetic? The answer is Little Jonny Evil—a game that makes you feel clever for helping a monster.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Elegance of Confinement

Core Loop & Puzzle Design: The entire game is a single, exquisitely designed puzzle. The loop is: 1) Observe the one-room environment (a cluttered, ominous basement). 2) Interact with objects via point-and-click. 3) Combine items in inventory or use them on scene hotspots. 4) Discover the sequence of actions that opens the door. Its nomination for “Best Puzzles in an AGS Game” was well-deserved. The puzzle is not about logic in the traditional Myst sense, but about causal malevolence. You must think like Jonny: what combination of objects, when manipulated, causes enough noise, distraction, or structural failure to defeat the lock? It’s a puzzle of effects, not of pure deduction.

Innovation within a Microcosm:

* Environmental Storytelling as Gameplay: Every object in the room isn’t just a puzzle piece; it’s a character note. A broken toy, a tool rack, a P.O. box—they collectively paint Jonny’s history and hobbies. You learn about him by what he deems useful for his escape.

* Lack of Traditional Feedback: As noted by a player (“Creamy” on AGS), “the lack of feedback for most actions is a little off-putting, especially since the hotspots are not shown.” This is a feature, not a bug. The absence of cursor changes or text prompts forces the player to experiment with the environment as a child would—through relentless, consequence-driven trial and error. The “aha!” moment is born of environmental mastery, not UI clues.

* Inventory as a Manifesto: The limited inventory (likely 3-4 slots) forces prioritization. What is the ultimate tool for escape? A hammer? A fuse? The player curates Jonny’s “kit” of destruction.

Flaws as Features: The game’s shortness is a common critique (“OK, it´s pretty short but it doesn´t claim to be a full lenght game” – Broken Sword on AGS). Yet, its brevity is its greatest strength. It is a perfect, unexpanded vignette. Any longer, and the conceit would strain. The “one-room” constraint, which could feel limiting, instead creates a profound sense of intimacy and pressure. You are trapped with Jonny’s mind until the solution is found.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Basement as Liminal Space

Visual Direction & Artistry: Without access to high-resolution screenshots in these sources, we must infer from its reputation and era. The game’s nomination for “Best Room Art in an AGS Game” suggests a detailed, atmospheric, and character-filled environment. The basement is not a generic grey box; it is a lived-in space of confinement, filled with the detritus of a disturbed childhood. The 256-colour palette forces a moody, expressive use of limited hues—likely browns, greys, and sickly yellows. The pixel art, within the AGS 2002 context, would have been crisp and expressive, with careful attention to the “weight” of objects (a heavy toolbox versus a light piece of paper). The art tells the story before Jonny animates.

Sound Design & Atmosphere: The AGS page notes a “very suitable” soundtrack. This is crucial. In a one-room game, audio does heavy lifting. The soundtrack likely consists of low, tense ambient drones, perhaps with a subtle, unsettling melodic motif representing Jonny’s cunning. Sound effects—the clink of a tool, the creak of a floorboard, the final, satisfying click of a lock—are the primary feedback mechanism where the UI is absent. They are the game’s voice, punctuating moments of experimentation and the climax of escape.

Atmosphere as a Character: The combination creates a “liminal” space—a threshold between childhood and something else, between safety and chaos, between punishment and consequence. The basement is a psychological space as much as a physical one. The art and sound collaborate to make it feel both claustrophobic and full of latent, dangerous potential.

6. Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Underappreciated

Contemporary & Modern Reception: In 2002, Little Jonny Evil existed in the niche AGS community. Its three award nominations (Player Character, Puzzles, Room Art) signal significant peer respect within its specific ecosystem. However, it won nothing, perhaps a victim of its own obscurity or the challenging nature of its protagonist. The single MobyGames user rating is a 3.0/5, reflecting a “good but not for everyone” consensus. Player comments on AGS are generally positive (“fun little game,” “Great Graphics… alot of fun”) but sparse, a testament to its forgotten status outside the most dedicated retro-adventure circles.

Influence on the Industry: Its direct influence is, by necessity, minimal. It did not spawn clones or a genre. Its legacy is one of possibility. It stands as a powerful argument for the “micro-adventure” and the “concept-first” design. It prefigured the “escape room” genre boom by years but with a subversive narrative twist rarely replicated. More broadly, it is a canonical example of the AGS engine’s potential for creating tight, stylistically bold experiences outside the commercial mainstream. For every Blackwell or Gemini Rue that achieved wider acclaim, there were dozens like Little Jonny Evil proving that a single compelling idea, executed with precision, could be a complete and satisfying game.

Rediscovery & Preservation: Its presence on the Internet Archive and My Abandonware is crucial. It is a preserved artifact of a specific moment in indie game development—the democratization of adventure game creation. It is studied today not as a lost classic but as a fascinating case study: what can you do with one room, one protagonist, and a clear, dark premise?

7. Conclusion: A Basement for the Ages

Little Jonny Evil is not a great game in the conventional sense. It is not lengthy, mechanically deep, or narratively sprawling. It is, however, a perfect game of its kind. Its genius lies in its unwavering commitment to a single, brilliant premise: the player is an accomplice to a psychopathic child’s escape. Every design decision—from the one-room constraint to the lack of UI hints—reinforces this premise, creating a cohesive, humorous, and deeply unsettling experience that lingers long after the final door click.

Its historical importance is twofold. Firstly, it is a high-water mark for the “bite-sized” adventure, proving that profound storytelling and engaging puzzle design do not require 40-hour playtimes. Secondly, and more importantly, it represents the fearless creativity of the early 2000s indie scene. It is a game that could only have been made outside the commercial system, by a creator with a twisted idea and the skill to execute it perfectly in a constrained tool.

In the end, Little Jonny Evil is a ghost in the machine of gaming history. It is rarely discussed, seldom played, but impossible to forget. It is the ultimate proof that in the art of game design, scale is irrelevant next to audacity. You will remember helping Jonny escape. And you will wonder, as he vanishes into the house above, what “playing with dangerous toys” truly means. For that lingering question, this short, sharp, brilliantly evil game secures its place as a timeless, if niche, masterpiece.

Final Verdict: 4.5/5 – A Cult Classic of Micro-Design and Subversive Storytelling.