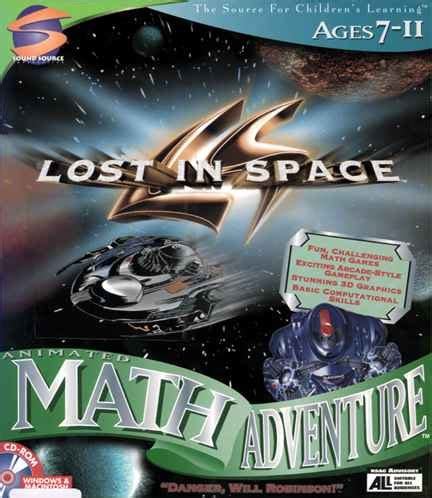

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Sound Source Interactive, Inc.

- Developer: WayForward Technologies, Inc.

- Genre: Educational, logic, Math

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Math puzzles, Mission-based, Space Exploration

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

Lost in Space: Animated Math Adventure is a children’s educational math game based on the Lost in Space film, set in a sci-fi space environment. Players select missions and difficulty levels to solve math problems through activities like blasting space spiders, navigating asteroid fields, and guiding robots, all aimed at reconstructing the stargate to help the Jupiter 2 crew return home.

Lost in Space: Animated Math Adventure: Review

Introduction: A Forgotten Frontier in Educational Gaming

The late 1990s represented a golden age for childhood educational software, a period where the burgeoning CD-ROM format allowed developers to dream beyond simple flashcards and drill sheets. Publishers plastered beloved cartoon and film licenses onto core learning concepts, banking on brand recognition to sell titles that often prioritized spectacle over pedagogy. Within this crowded marketplace, Lost in Space: Animated Math Adventure (1998) stands as a curious, almost spectral, footnote. Developed by a nascent WayForward Technologies and published by Sound Source Interactive, this title attempted to fuse the narrative optimism and peril of the 1998 film remake with the era’s signature “edutainment” formula. Yet, for a game based on one of science fiction’s most iconic families, it has all but vanished from collective memory, collected by a mere handful on preservation sites. This review will argue that Animated Math Adventure is not a failed game per se, but a compelling artifact of its time—a product of technological limitations, corporate licensing strategy, and a sincere (if clumsy) attempt to make arithmetic feel like an interstellar adventure. Its true legacy lies not in its gameplay innovations, but in its position as a bridge between the point-and-click adventure aspirations of its developer and the rigid, drill-focused expectations of the educational market.

Development History & Context: WayForward’s Pre-Shantae Foray and the CD-ROM Gold Rush

To understand Animated Math Adventure, one must first place it within the career trajectory of its developer, WayForward Technologies. In 1998, WayForward was not the acclaimed indie studio behind modern classics like Shantae or River City Girls. It was a small, ambitious outfit founded by Veutro Brazelton, primarily churning out licensed games and utilities for the burgeoning home computer market. Their portfolio from this era includes titles like X-Men: Mutant Apocalypse (1994) and, critically, a series of “Animated” educational games including Dinonauts: Animated Adventures in Space (1995) and, most directly, Lost in Space: Animated Learning Adventure (1998)—a sister product focused on science rather than math. This reveals Sound Source Interactive’s strategy: leveraging a single license to create multiple genre-specific products, maximizing return on a costly film rights acquisition.

The technological context is equally vital. The game targets Windows 95 and Macintosh System 7, squarely in the pre-3D acceleration era. “Very 90s graphics, but not pixel art. It was all supposed to be 3D,” notes one player recollection on Reddit, capturing the era’s aesthetic dilemma. Developers used 2D sprites rendered with a faux-3D perspective (often called “2.5D”) or early 3D engines like RenderWare to create the illusion of depth on hardware that could barely handle textured polygons. This technical constraint directly shaped the game’s visual identity: likely a dark, industrial color palette of greys, blacks, and blues—as remembered by a user seeking the title—with sparse colored lighting to denote functionality, all built to mask low polygon counts and limited draw distances.

Commercially, 1998 was the tail end of the CD-ROM boom. Educational titles were a staple of the “edutainment” section in big-box retailers, often sold in oversized “big box” packaging (as seen on eBay listings) that promised a premium experience. Lost in Space (the film) had underperformed at the box office but maintained a cult following, making it a somewhat risky yet potentially低成本 (low-cost) license for a publisher like Sound Source. The game’s simultaneous Windows and Macintosh release was standard for cross-platform educational software aimed at schools and home users alike.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Rebuilding the Stargate, One Equation at a Time

The narrative framework of Animated Math Adventure is simplicity itself, lifted directly from the film’s MacGuffin: the broken stargate. According to MobyGames, “the goal is to complete missions to reconstruct the stargate that will allow the crew of the Jupiter 2 spacecraft to return home once again.” This is not a story-driven game in the adventure game sense; there is no dialogue tree, character arc, or plot twist. Instead, the narrative is a meta-justification, a ludonarrative bridge where each successfully completed math mission corresponds to retrieving a “piece” of the gate. This approach reflects a common design trope in 90s educational games: the “mission” structure, where learning is the means to an end (returning home), not the end itself.

Thematically, the game implicitly promotes several values central to the Lost in Space IP:

* Problem-Solving as Survival: The Robinson family’s core trait is applying intellect to dire circumstances. Here, that intellect is narrowly channeled into mathematical computation. Solving a multiplication problem to blast a space spider isn’t just gameplay; it’s framed as a necessary act of self-preservation.

* Teamwork via Solitary Play: While the film emphasizes family collaboration, the game places the player in the singular role of the “leader of The Milky Way Project” (as seen in its sister science game). This subtly reinforces a heroic, individualist narrative common in American educational software, where one child’s prowess saves the collective.

* Science as Adventure: By setting math problems within “blasting space spiders,” “navigating an asteroid field,” and “guiding a robot through a lava field” (per LaunchBox), the game attempts to recast rote arithmetic as a dynamic, high-stakes endeavor. The dark, industrial space station aesthetic—as recalled by the Reddit user—further divorces math from the classroom and places it in a realm of “treacherous environments.”

However, the narrative is paper-thin. Character roles are non-existent beyond asset usage. The player never interacts with Will, Dr. Smith, or the Robot in any meaningful way. The Jupiter 2 is merely a vehicle (“zooming through space”) and a backdrop for keypad-locked doors (a Reddit user’s vivid memory of “unlock[ing] doors between sections of the ship… via keypad and basic math”). This suggests missions may have been spatially linked within a hub, but the narrative integration stops at the stargate premise. Thematically, it’s a superficial layer, a branded veneer over what is essentially a customizable math drill engine.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Drill Engine Disguised as Adventure

At its core, Animated Math Adventure is a sophisticated menu-driven math drill system wrapped in a thin adventure shell. The core loop is defined by the main navigation area: the player selects a mission (e.g., Asteroid Field), a math subject (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division), and a challenge level (four tiers of difficulty). This modular design was progressive for its time, allowing for personalized learning pathways—a student weak in multiplication could practice exclusively in a lower-difficulty “Lava Field” mission without being penalized by other subjects.

Mission Breakdown & Gameplay Synthesis:

1. Blasting Space Spiders: Likely a shooting gallery or fixed-screen action sequence. The player must solve a math problem to fire a weapon. The Reddit user’s memory of “destroy[ing] alien ships by completing the math problems on them” perfectly aligns with this, though they conceded it might be conflated with other games. This represents the most “arcade” integration.

2. Navigating an Asteroid Field: This suggests a timing or pathfinding game. Perhaps the player must calculate trajectories or sequences (e.g., “press the button when the next asteroid is 5 units away”) to pilot the Jupiter 2 safely.

3. Guiding a Robot Through a Lava Field: This implies a logic puzzle or sequence input. The player might program the B9 Robot’s movements by solving math problems that determine safe stepping stones across a hazardous grid.

4. Zooming Through Space in the Jupiter 2: A likely simple reflex or pattern-mognition task, where math answers control speed or direction to avoid obstacles.

5. Reconstructing the Stargate: The meta-game. Success in the four other missions (the source lists five, but the stargate reconstruction is the fifth; LaunchBox lists four action missions plus the gate) yields components. The final assembly may involve a culminating math challenge.

The Innovative (and Flawed) Systems:

* Dynamic Difficulty: The four skill levels per subject are the game’s most significant pedagogical feature. This acknowledges that “multiplication” is not a monolithic skill; a “Level 1” might involve single-digit products, while “Level 4” could include multi-digit or decimal operations. This prevents frustration and allows growth.

* The Illusion of Choice: The mission selection provides thematic variety, but the underlying math is identical across themes at the same difficulty level. A subtraction problem in the “spider” mission is the same as in the “lava” mission. The setting is pure reskinning.

* The Keypad Puzzle: The Reddit user’s specific memory of “doors between sections of the ship that you had to unlock via keypad and basic math” is crucial. It suggests a hub world—a 3D-rendered Jupiter 2 interior—where progression is gated not by mission completion but by solving math problems on-terminal keypads. This would have been a significant innovation, blending exploration (even if limited) with applied math in a context that felt diegetic (the door to Engineering requires a code). Its implementation is unknown—were these random problems or tied to the mission theme?

* UI & Feedback: Presumed to be minimal: a large, clear problem display, multiple-choice or input fields, and immediate auditory/visual feedback (explosions, robot movement). The “animated” quality likely refers to cutscenes or sprite animations upon correct answers, providing the reward that pure drill software lacked.

The fundamental flaw is ludonarrative dissonance. The math is not integrated into the game’s logic; it is a tax to trigger the pre-scripted action. The asteroids don’t move according to the player’s calculation; the calculation merely unlocks the next screen. This makes the “adventure” a series of discrete, non-interactive vignettes bookended by computation. It respects the educational goal (math practice) but betrays the adventure promise.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Industrial太空 and Synthwave Ambiance

The game’s setting is the Lost in Space universe transposed into an educational context: the damaged Jupiter 2 and the surrounding void. The Reddit user’s description—”very dark setting, a lot of it was grey/black/blue with spatterings of color for lights on the ship”—is telling. This was likely a stylistic and practical choice. A dark palette with point-source lighting (consoles, emergency lamps) is cheaper to render in software 3D and simultaneously conveys a “damaged, emergency situation” atmosphere that justifies the player’s interventions. It’s a compromise that oddly enhances the主题 tone of peril.

Visual Direction: The “animated” in the title suggests a cel-shaded or cartoonish art style, distinct from the darker film. This aligns with the 1998 film’s own aesthetic, which was a grittier, more industrial take on the 60s original. The game probably uses pre-rendered 2D sprites for characters (Will, Dr. Smith, Robot) against 3D backgrounds, a common technique (e.g., Final Fantasy VII). The “circular portals” mentioned by the Reddit user—”you could link up pieces of circular portals outside the ship that you could activate and fly through”—is evocative. This might describe the stargate reconstruction interface or a mission transition, where math success “activates” a portal graphic. It’s a strong, memorable visual hook that the sources imply but do not confirm.

Sound Design: The sources are silent on audio, but we can infer from the license and era. The game almost certainly uses library music or, if budget allowed, adapted cues from the film’s score (Bruce Broughton’s iconic themes). Sound effects for laser blasts, robot movements, and UI clicks would be generic but functional. The “animated feel” the Reddit user mentions might refer to full voice acting—a rarity for budget educational titles—but more likely points to smooth sprite animations for interactions. The Steam page for the new Lost in Space adventure game (2026) highlights using “dialogue taken directly from the show,” but this is irrelevant to the 1998 title, which had no such access.

The atmosphere is one of urgent exploration. The darkness isn’t just an aesthetic; it’s a narrative device. The ship is broken, power is low (as the newer game’s developer discussions about “the ship currently has no power” ironically echo), and math is the tool to restore light and function. This successfully leverages the Lost in Space IP’s core conflict: intellect vs. cosmic adversity.

Reception & Legacy: A Ghost in the Machine

Contemporary Reception: There is virtually no record of critical or commercial reception. MobyGames shows zero critic reviews and only two collectors. The absence is deafening. This suggests the game was neither a breakout hit nor a notorious flop; it was a catalog filler, likely sold alongside Math Blaster and Reader Rabbit in the educational aisle, quickly overshadowed by bigger brands. The fact that it was bundled with “Entertainment Utility” software (per eBay) indicates it was part of multi-title compilation packs, a common way to move stagnant inventory.

Evolution of Reputation: Its reputation has evolved into pure obscurity, buoyed only by the occasional nostalgia-driven “tip of my tongue” Reddit thread. The user’s detailed query—”late 90s/early 2000s educational game involving space stations and math… dark setting… keypad doors”—is almost certainly describing Animated Math Adventure, though they doubted it. This memory, preserved in a 2019 forum post, is now one of the most detailed public records of the game’s feel. It reveals what stuck: the atmosphere (dark, industrial space station) and specific puzzle mechanic (math-based keypads), not the educational content.

Influence and Industry Position: The game had no discernible influence on the educational or mainstream gaming industries. WayForward would go on to greater things, but their early work in edutainment is a footnote. More broadly, Animated Math Adventure represents the last gasp of the pre-2000s “adventure-edutainment” hybrid. Post-2000, the genre bifurcated: pure drill software (like Math Blaster’s later iterations) became more gamified but less adventure-like, while serious adventure games shed their educational hooks. The game’s conceptual cousin in the modern era is the “game-based learning” movement, but that favors immersive simulations over discrete math problems.

Its true legacy is as a case study in missed potential. The assets (a spaceship hub, recognizable characters, thematic missions) were all there. A more ambitious design could have woven math into the environment: calculating oxygen levels, power distribution, or navigation coordinates in real-time as part of the exploration. Instead, it remained a glorified quiz show. The recent development of Lost In Space – The First Adventure (2026) by Scary Robot—a full point-and-click narrative adventure—highlights what could have been. That new game’s developer discussions on Steam, focusing on episodic storytelling and character authenticity, stand in stark contrast to the 1998 title’s functional, impersonal approach.

Conclusion: A Cursed Mission in the Edutainment Nebula

Lost in Space: Animated Math Adventure is not a good game by any conventional metric. Its gameplay is repetitive, its narrative is nonexistent, and its educational value is limited to repetitive arithmetic drills. Yet, as a historical artifact, it is fascinating. It captures a moment when a struggling film franchise could be licensed for a math game, when a future indie darling was grinding out utility software, and when the dream of “learning through play” was often realized through the simplest of gamification: a laser blast for a correct answer.

Its place in video game history is secure, albeit as a minor, almost forgotten, data point. It exemplifies the commercialization of educational gaming in the CD-ROM era—a period of ambition often hamstrung by shallow design and a fundamental misunderstanding of how to blend pedagogy with engagement. The game’s obscurity is its most telling legacy; it failed to capture the imagination of children or the respect of educators. But for the few who remember the eerie quiet of that dark Jupiter 2 corridor, the beep of a keypad demanding a sum to open a door, it remains a ghostly monument to a time when space exploration and times tables shared the same digital hull. It is a cautionary tale: even the most potent of licenses cannot compensate for a core loop that mistakes computation for adventure. The Robinson family’s real mission was to get home; this game’s mission—to make math matter—was lost in space long before release.

Final Verdict: 2/5 Stars. A historically noteworthy but fundamentally flawed artifact of the late-90s edutainment boom. Its value lies in preservation, not play.