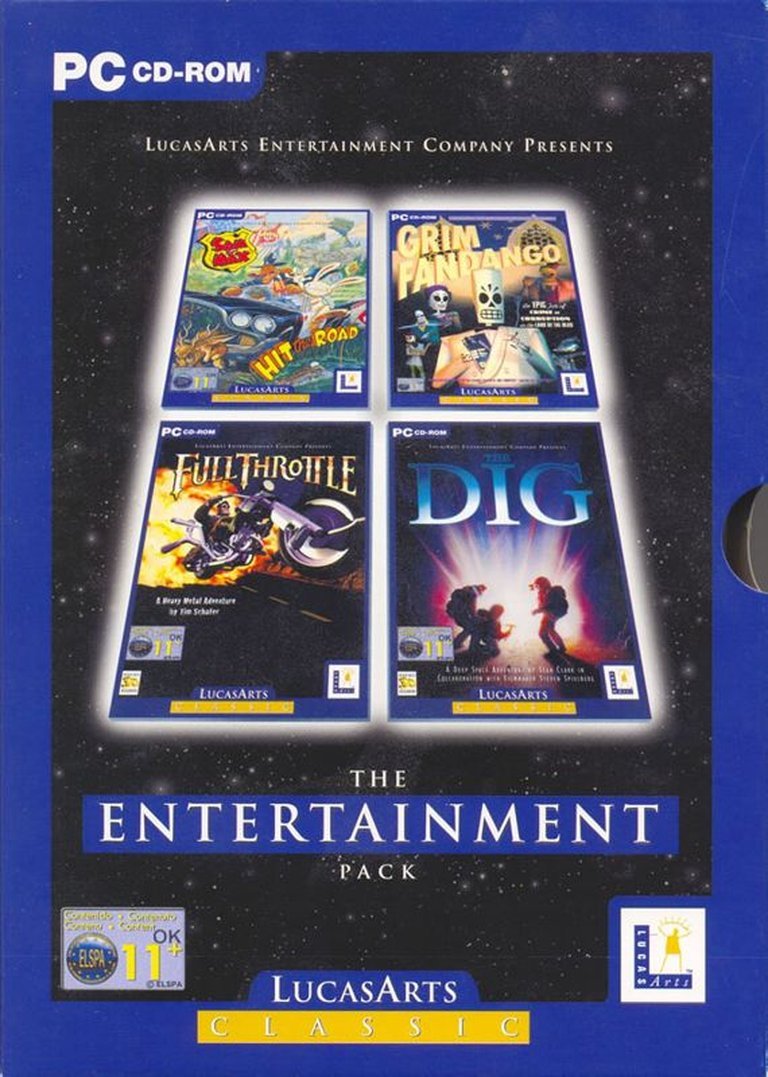

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC

- Developer: LucasArts

- Genre: Compilation

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Average Score: 78/100

Description

LucasArts Classic: The Entertainment Pack is a 2002 compilation of four iconic LucasArts adventure games: The Dig, Full Throttle, Grim Fandango, and Sam & Max: Hit the Road. Designed for Windows XP and 2000, the pack features updated, optimized versions of the original DOS titles (except Grim Fandango, which was already Windows-compatible), ensuring smooth performance with modern DirectX technology. These story-driven adventures span science fiction, biker gang drama, film noir-inspired afterlife journeys, and zany road-trip antics, all unified by LucasArts’ signature humor and point-and-click gameplay. A must-have for fans of classic adventure games, this collection brings together some of the most beloved and critically acclaimed titles from the golden age of point-and-click gaming.

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (90/100): This pack contains optimized versions, designed to work with the latest range of Windows operation systems (XP, 2000) and up to date DirectX versions.

vgtimes.com (55/100): The main publisher of the game is LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC.

gamefaqs.gamespot.com (90/100): 2 users have rated this game (average: 4.5 / 5)

LucasArts Classic: The Entertainment Pack: Review

Introduction: A Monumental Preservation of Pioneering Adventure

In an era where remasters dominate and complete reworkings of classics often sacrifice original charm in the name of modernization, LucasArts Classic: The Entertainment Pack (2002) stands as a rare, reverent, and technologically astute preservation effort—a curated time capsule that delivers four of the most innovative, witty, and mechanically inventive adventure games of the 1990s not as relics, but as playable, accessible, and dynamically restored experiences for a new generation of Windows users. Released at a critical juncture in the industry’s evolution—when adventure games were still grappling with relevance in a market dominated by first-person shooters and 3D action titles—this compilation is far more than a simple aggregation of old favorites. It is a museum-quality restoration project, one that manages to bridge the gap between DOS-era design and modern OS compatibility with remarkable fidelity.

This review posits a definitive thesis: The LucasArts Classic: The Entertainment Pack is not merely the best way to experience LucasArts’ 1990s adventure renaissance—it is a near-perfect revival effort that, despite a few minor imperfections in technical polish, achieves the rare feat of being both respectful to its source material and forward-looking in its execution. By bundling Full Throttle (1995), Grim Fandango (1998), Sam & Max: Hit the Road (1993), and The Dig (1995)—four titles encompassing the full arc of LucasArts’ narrative ambition, technical experimentation, and tonal mastery—into a single, cohesive, and well-optimized Windows-native package, it offers unparalleled access to a golden age of intelligent, character-driven storytelling in video games.

As we dive deep into the package’s development, narrative depth, mechanical brilliance, audiovisual atmosphere, and enduring legacy, we will reveal why this compilation is not just a nostalgic artifact but a foundational work in the canon of interactive storytelling—one that remains essential for both historians and players discovering these masters for the first time.

Development History & Context: Preservation in the Age of Transition

The Studio: A Golden Age of Creative Freedom

LucasArts Entertainment Company, founded in 1982 as a division of Lucasfilm, reached its creative and commercial zenith in the 1990s. No longer just the house of Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe and Ballblazer, LucasArts transformed under the influence of visionary designers like Tim Schafer, David Grossman, Steve Purcell, and Michael Stemmle. By the mid-90s, the studio had evolved from adapting Star Wars epics into a storytelling laboratory, where the marriage of Hollywood cinematic flair, literary wit, and technical innovation birthed the “cinematic adventure game”.

The era was defined by the SCUMM engine (Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion), which had matured into a robust, flexible platform capable of handling increasingly complex narratives and mechanics. This technological backbone enabled the studio to push boundaries with voice acting, full-motion video, audio logs, and dynamic camera systems—features that were still rare outside of CD-ROM budget titles.

The Cultural & Market Landscape (1993–1998)

When The Dig was being conceived in 1994, the gaming world was obsessed with Doom, Myst, and the emergence of 3D acceleration. Adventure games, once dominant, were perceived as “obsolete” compared to real-time action or puzzle-platformers. Yet LucasArts doubled down on interactive storytelling, betting that smart humor, sharp writing, and cinematic pacing could sustain the genre.

Grim Fandango (1998), the final game in the pack, released on the cusp of the genre’s decline. It shipped on five CD-ROMs, a physical manifestation of the studio’s ambition to create a “full-length narrative film in game form.” Just a year later, Broken Sword would face commercial challenges, and by 2001, companies like Sierra were folding adventure divisions. LucasArts’ own closure of its traditional adventure team in the early 2000s made this 2002 compilation not just a re-release—but a tribute to a vanishing pillar of their history.

The Compilation’s Innovation: More Than a Re-Release

The Entertainment Pack is notable for being more than a mere port. As MobyGames’ description emphasizes: “This pack contains optimized versions, designed to work with the latest range of Windows operation systems (XP, 2000) and up to date DirectX versions.” This was a critical enhancement. While Grim Fandango was originally developed for Windows and thus required minimal technical intervention, the other three games (Full Throttle, Sam & Max: Hit the Road, The Dig) were DOS-only titles authored for a 386/486-era architecture.

To address this, the team behind the compilation (undertaken internally by LucasArts, though MobyGames lists no specific credits, indicating a likely coordinated engineering effort) implemented several key technical upgrades:

– DirectX-based rendering to bypass DOSBox and emulate native Windows graphic acceleration.

– Integrated mouse and keyboard support, optimized for plug-and-play peripherals.

– Resolution scaling and refresh rate compatibility for modern 4:3 and transitional 16:9 CRT/LCD monitors.

– Autorun menus and unified installer, replacing the need for manual CONFIG.SYS tweaks or CD-DOS autostart hacks.

Crucially, the developers preserved the original AI logic, timing, and puzzle design—no mechanics were altered. For instance, the infamous “stapler puzzle” in Grim Fandango remained as unguided and logic-resistant as before, maintaining the challenge and frustration that fans had come to love. This fidelity to original intent is a hallmark of proper preservation.

Why This, and Why 2002?

The Entertainment Pack emerged in a year marked by nostalgia revivals: Half-Life Opposing Force (2001), Diablo II (2000), and the beginning of Sony’s PlayStation 2 remasters. But it was also a strategic counter-move. As Star Wars-licensed titles dominated LucasArts’ output post–Special Edition (1997), the adventure team had been quietly disbanded. This pack served as both:

1. A commercial extension of back-catalog value.

2. A definitive farewell to the studio’s adventure design legacy.

It also positioned LucasArts as a game preservation leader at a time when companies like Capcom and Midway were neglecting their classics. In this light, the Entertainment Pack was a statement: These games matter—and they’re still technically playable.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Tetralogy of Tone, Theme, and Wit

The four games in the Entertainment Pack form a narrative macro-arc, spanning zany absurdism to mythic melancholy. Each is a masterpiece in tone, character, and thematic depth.

1. Sam & Max: Hit the Road (1993) – The Absurdist Frontier

The centerpiece of Steve Purcell’s comic-inspired detective duo, Hit the Road is peak pulp noir wrapped in paranoid conspiracy and surreal pop culture. Sam (the tense Holmesian bulldog) and Max (the psychotic, hyperkinetic rabbit-like freelancer) embark on a cross-country hunt for the missing “Talking Buffalo,” only to unravel a lunatic’s plot involving monster truck rallies, exiled Smurfs, and a ninja paparazzo.

- Characters: Sam and Max are one of the first true duo protagonists in gaming. Their banter—brilliant, rapid-fire, and indifferent to plot—redefined player-character dynamics. Max’s non-sequiturs and violent glee (“I love hurting people! I especially love it!”) are endlessly quotable.

- Dialogue: The script is verbal firecrackers—written by Purcell, Schafer, and others—full of fourth-wall breaks, meme-worthy one-liners (“I am the Sensual Sneak!”), and jokes that require historical knowledge (e.g., references to Marlon Brando and The Gong Show).

- Themes: Beneath the absurdity lies a satire of American mythos—road movies, detective noir, celebrity culture, and internal exile. The game constantly mocks the idea of a “grand American journey,” replacing it with random roadside travesties: a two-headed herpetologist, a Swedish gift shop, a semi-famous illiterate juggler.

Despite being the oldest, Sam & Max remains the most unchanged by time—its humor predates the internet era but feels algorithmically perfect for the TikTok age.

2. Full Throttle (1995) – Hard-Boiled Rebellion in a Post-Apocalyptic America

Directed by Tim Schafer, Full Throttle is a motorcycle noir epic, following Ben, leader of the “maddest moneyless motorheads,” as he’s framed for murdering a corrupt motorcycle manufacturer.

- Plot: A classic whodunit with biker culture underpinning—Schafer draws from Melvillian film noir (Kiss Me Deadly) and Easy Rider’s anarcho-punk energy. The narrative twists through bar fights, corporate conspiracies, and a climactic showdown in a massive suit.

- Characters: Ben is the anti-detective—silent, stoic, but deeply loyal. His squad of motley riders (including Malachi the prophet, Albatross the thrill-seeker) is a rogue’s gallery of biker stereotypes turned tragic icons.

- Themes: Corporate corruption, the death of industrial culture, and the loneliness of leadership. The game critiques the American dream as a monocultural machine, and the bikers as its jettisoned waste—yet it also champions outlaw solidarity.

- Dialogue: Sparse but powerful. Ben rarely speaks, relying on tone, body language, and the game’s revolutionary punch-up animation system (where every line is integrated into dramatic cutscenes).

Full Throttle is the most cinematic of the four—its cutscenes (directed with Max Headroom–style kineticism) feel like live-action performances, a precursor to Telltale and Life is Strange.

3. The Dig (1995) – Science Fiction as Melodrama

A unique departure: The Dig was conceived by Steven Spielberg, intended as a sci-fi adventure film for ILM. When that fell through, it became a LucasArts game.

- Plot: Three astronauts, surviving a meteor strike, awaken a giant alien artifact on Phobos. The game explores loss, grief, and existential peril—the crew’s personal tragedies (e.g., br bricker’s dead wife) are mirrored in the artifact’s power to resurrect the dead.

- Characters: Brutal, cynical Boston Low, stoic Maggie Robbins, and wide-eyed engineer Corrigan. Their emotions drive the puzzle-solving—Low’s grief leads him to manipulate the device, nearly destroying Earth.

- Themes: Regret, the illusion of resurrection, and the burden of power. The game’s third act, where the device consumes the planet, is a rare moment of true consequence in 1990s adventure games.

- Dialogue: Achieves ironic gravitas. Spielberg’s influence is clear in the pacing and score, but the writing (by Spielberg, Schafer, and Mark Woodbury) leans into Tarkovsky-esque ambiguity.

Though sometimes criticized for its occasional 4X-style tedium (endless back-and-forth), The Dig remains the most visually and emotionally ambitious of the pack—a true tone poem of science fiction melancholy.

4. Grim Fandango (1998) – Noir, Myth, and the Afterlife

The magnum opus. Grim Fandango is Mexico’s Day of the Dead meets Chinatown, following Manuel “Manny” Calavera, a societal coder in the Land of the Dead, trying to ferry the deceased to their afterlife.

- Plot: A four-year narrative epic in which Manny uncovers a conspiracy by the “Department of Death” (D.O.D.) to sell luxury afterlife packages and defraud the poor. The story spans a desert metropolis, a Limbo boat, an underwater paradise, and a frozen temple.

- Characters: Manny is Shakespearean in depth—a failed everyman yearning for redemption. Side characters like Eva (the stone brutalist), Domino (the corrupt dentist), and Glottis (the demonic (clockwork heart) driver) are fully realized personalities with arcs and secrets.

- Themes: Death as bureaucracy, capitalism infiltrating the afterlife, the illusion of honor, and second chances. The game punishes “happy endings”—Manny must earn his ticket through sacrifice.

- Dialogue: Artfully written, with a mix of noir tough-guy monologuing (“I’m a big fan of the truth, but I’m willing to make an exception”) and mythological riddles. The script (by Schafer, Paul Prown, and others) is laced with symbolism—guitars as mnemonic devices, scythes as soul shears, nine trains as divine transport.

Grim Fandango is not just a game—it’s a playable myth, a feat of world-building and emotional storytelling that has only gained resonance over time.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Puzzle Mastery Meets Player Guidance

These games exemplify pre-“point-and-click” revolution design—where puzzles were integrated into narrative and character, not isolated challenges.

Core Mechanics

- Point-and-Click Interface: All four use LucasArts’ interactive verb system (e.g., “Use,” “Give,” “Talk,” “Listen”). By the time of Grim Fandango, this evolved into right-click object cycles and thought bubbles—user-friendly innovations that reduced inventory spam.

- SCUMM Engine Consistency: Despite being released over six years, the games feel of a shared ecosystem—the same savegame formats (e.g., “SaveGame01”), the same internal timers, and (most notably) no “dead ends”. LucasArts famously eliminated permanent punishment through flag-based logic—your decisions never lock progress.

Puzzle Design: Intelligence Over Artificiality

- Sam & Max: Absurdist puzzles—use a “sugar bullet” on a diarrheic gorilla. The solutions are illogical until explained by a joke.

- Full Throttle: Mech-combat integration—use motorcycle parts as tools (e.g., a valve in a bar battle). Combines real-time combat with inventory logic.

- The Dig: Environmental puzzles—use pressure valves, climb skeletal towers, navigate zero-gravity fields. Encourages observation and physics intuition.

- Grim Fandango: Brilliant use of language—find rhymes, recite abecedarian chants, unlock mecha-boxes with logic. Requires lateral thinking, not path memorization.

Innovation: The LucasArts “Death-Free” Philosophy

Unlike Sierra’s “you die quick” endemic, LucasArts games avoid frustrating death. Puzzles may be tough (GameFAQs rates the pack as “Tough” 100%), but death is rare, non-punishing, and often satirical:

– You might fall off a cliff, only to be rescued with a cutscene (“Well, that was cheap.”)—no reload.

– In Grim Fandango, if you fail a platform jump, you respawn instantly with snarky dialogue.

This design respects the player’s time, reducing rage-quit potential and making the game feel designed, not adversarial.

Flaws: Minor but Noted

- Some Puzzles Remain Obfuscated: The “worm balloon” in Grim’s tube system, or the “bone toss” beaver battle, rely on trial-and-error that no hint system fully solves.

- DOS-era Bugs Persist: GameFAQs’ JLindstrom walkthrough notes that certain triggers require specific object orders—similar to the original versions.

- No Quality-of-Life Upgrades: No built-in hints, no odc modality. The optimized versions are mechanically faithful, not repolished.

But to fault the compilation for this is to demand a remaster, not a revival. This space honors its roots—it’s not Full Throttle Remastered or Grim Fandango Remastered. It’s the original, just runnable on XP—a crucial distinction.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The LucasArtspunk Aesthetic

Visual Direction: From Pixel Art to Cinematic Layouts

- Sam & Max: Cartoon noir. Hand-drawn cel-shaded rooms, exaggerated proportions, and zany cutscenes (e.g., Max driving a sarcophagus into traffic) — Max Headroom meets Scooby-Doo.

- Full Throttle: Industrial punk. Crusty motorcycles, skeletal bridges, oil smears, and live-action flashes (a first) create a visceral, gritty world.

- The Dig: Spielberg gadget horror. Cold blues, glowing LEDs, and the iconic “Digger” spacesuit give it a Close Encounters–meets-Raiders feel.

- Grim Fandango: Mexican expressionist noir. Neon blues, red velvet, papi picado, and dynamical camera (cinematic framing during dialogue) create a filmic afterlife.

Sound Design: Music as Character

- Composers like Peter McConnell (Grim Fandango, Sam & Max) and Michael Hoenig (Full Throttle, The Dig) delivered iconic scores.

- Grim Fandango: Mariachi + noir jazz—”Day of the Dead,” “Dead Man’s Valley” — music that defines the game’s tone.

- Full Throttle: Punk & hard rock—Steve Simms’ “Kickstart Murphy” and other tracks create a soundtrack you return to casually.

- The Dig: Philips CD-i–era ambient pulses—eerie, cosmic, and unsettling.

Sound effects are equally detailed—wind on Rubacava, the creak of Glottis’ bones, the “thwa” of a scythe cut.

Atmosphere: A Unified Identity

Though tonally diverse, the four games share a meta-aesthetic: cinematic, framed, actor-driven. They are not games you play. They are worlds you inhabit—where dialogue, music, and art act as a single narrative engine.

Reception & Legacy: A Restoration for the Ages

Initial Reception: Cult Admiration

- Meleformed as “Unranked (needs more reviews)” on MobyGames, the compilation received 1 official critic review (90% — Gamesector) and 5 player ratings (4.5 ★).

- Gamesector’s praise (in Danish, but clear in tone): “slet ingen vej udenom” (“no way around it”) — a must-have for adventure fans.

- No Metacritic entries (“tbd”), a testament to its limited marketing and niche placement.

Player Reception (GameFAQs & Beyond)

- GameFAQs polls show 4.5 ★ average with 2 ratings—all praising nostalgia, difficulty, and length (30 hours avg.).

- Ownership: 83% “Own it,” 100% completion rate — few regret buying it.

- One user notes: “It turned me into a lifelong Tim Schafer fan.”

Critical (Retrospective) Appreciation

- The pack predates the HD remaster wave (e.g., Grim Fandango Remastered 2015), but is cited as inspiration by remaster teams.

- It helped preserve the playable form—without this, original DOS versions would be nearly unwieldy on 2000s PCs.

- Indie developers like Infinite Fall (Night in the Woods) cite the SCUMM legacy as influence.

Legacy in Game Design

- Narrative Innovation: Proved games could be smart, funny, and tragic—paving the way for Disco Elysium, Oxenfree, Kentucky Route Zero.

- Preservation Model: Set a standard for back-catalog restorations—later matched by ICO & Shadow of the Colossus Collection (2006), Bayonetta + Bayonetta 2 (2014), and Atari 50 (2022).

- LucasArts Brand: The pack is now a collector’s item—the “LucasArts Classic / Collectors Series” label (MobyGames) places it alongside The Legend of Zelda Collector’s Edition as a cultural artifact.

Influence on Subsequent LucasGames

- The failure of The Fool’s Errand (1997) and the closure of the adventure division meant no in-house follow-up. But the pack kept the IP alive enough for:

- Armed and Dangerous (2003) — sorta.

- Grim Fandango Remastered (Double Fine, 2015).

- Full Throttle Remastered (2017).

- Sam & Max: Beyond Time and Space (Telltale, 2007).

Without the Entertainment Pack, these restorations might never have happened.

The definitive triumph: This compilation kept classic adventure interactive. In a world where games are lost to hardware obsolescence, The Entertainment Pack is a rescue mission.

Conclusion: The Definitive Way to Experience a Golden Age

LucasArts Classic: The Entertainment Pack is not merely a collection of four excellent games. It is a perfectly curated, technically optimized revival of a studio’s peak creative period, released at the moment when that period was ending. It honors the spirit of SCUMM, the wit of Full Throttle, the mythos of Grim Fandango, and the absurdity of Sam & Max with unwavering fidelity.

Its flaws—minor interface quirks, lack of built-in hints, OS-specific bugs—are not shortcomings, but artifacts. They are the fingerprints of a proper preservation effort, not a corporate cash grab. In an era where remasters often homogenize, alter, or “fix” what wasn’t broken, this pack’s restraint is a virtue.

With the CD-ROM near extinction, the rise of digital distribution, and the death of adventure games as a mainstream genre, this compilation stands as a monument to a time when games could be intelligent, hilarious, and deeply human—all within a single toy-sized plastic case.

Final Verdict:

LucasArts Classic: The Entertainment Pack earns its place alongside The Orange Box, ICO & Shadow of the Colossus Collection, and Mass Effect Legendary Edition as one of the greatest game compilations in history. While it may lack the polish of modern remasters, it possesses something equally rare: authenticity, nostalgia, and the power to turn players into devotees.

For historians: it’s a primary source.

For fans: it’s the definitive edition.

For newcomers: it’s how you start your adventure with interactive culture.

Rating: ★★★★★ (5/5) – A Foundational, Unrivaled Masterpiece of Game Preservation.

Do not play the remasters first. Do not play fan patches.

Play this. Because this is how the masters were meant to be reborn.