- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Amiga, BeOS, GP2X, Linux, Macintosh, Maemo, Palm OS, Wii, Windows

- Publisher: New Breed Software

- Developer: New Breed Software

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Fixed / flip-screen

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

Mad Bomber is a fast-paced arcade action game where players control a stack of water-filled buckets at the bottom of a fixed-screen to catch bombs dropped by a mad bomber from the top. The objective is to extinguish the falling explosives in the buckets before they hit the ground, as each miss removes a bucket until none remain, ending the game; it features single-player survival mode and two-player options for cooperative or competitive play, serving as a clone of the classic Kaboom! and available on multiple platforms since its 1999 Linux debut.

Gameplay Videos

Mad Bomber Free Download

PC

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

newbreedsoftware.com (80/100): Mad Bomber is a great game, and if you are a fan of Kaboom, by all means download this game. It’s not groundbreaking, but it is one of the best clones of Kaboom you’ll find on the net.

Mad Bomber: Review

Introduction

In the annals of video game history, few titles evoke the raw, unfiltered thrill of 1980s arcade simplicity quite like Kaboom!, the 1981 Atari 2600 classic from Activision that turned frantic bomb-catching into an addictive test of reflexes. Enter Mad Bomber, a 1999 open-source homage developed by New Breed Software that faithfully resurrects this formula for modern (at the time) computing platforms. As a game historian, I’ve pored over countless retro revivals, but Mad Bomber stands out for its unpretentious devotion to its predecessor while adapting to the open-source ethos of the late ’90s Linux scene. This isn’t a flashy reboot with HD graphics or convoluted lore—it’s a digital time capsule, capturing the essence of paddle-controlled chaos in an era dominated by sprawling RPGs and 3D epics. My thesis: Mad Bomber proves that timeless gameplay loops, when cloned with care, can outlast technological fads, cementing its place as a bridge between Atari’s golden age and the indie open-source revolution.

Development History & Context

Mad Bomber emerged from the fertile ground of New Breed Software, a one-man operation helmed by Bill Kendrick, a prolific Linux developer known for educational titles like Tux Paint and arcade clones such as Circus Linux!. Released initially in 1999 for Linux, the game was Kendrick’s tribute to Larry Kaplan’s Kaboom!, which itself was envisioned as an Atari 2600 port of the 1978 arcade game Avalanche. Kaplan, a co-founder of Activision, designed Kaboom! to leverage the Atari’s paddle controllers for precise, fluid movement—a mechanic that Kendrick sought to emulate using mouse or keyboard input on PC hardware.

The late 1990s gaming landscape was a stark contrast to the ’80s console wars. PCs were exploding in popularity, but the open-source movement, fueled by Linux’s rise, emphasized free, accessible software over proprietary blockbusters. New Breed Software embodied this spirit, licensing Mad Bomber under the GPL to encourage ports and modifications. Technological constraints played a pivotal role: Linux lacked the polished game engines of today, so Kendrick relied on the Simple DirectMedia Layer (SDL) library for cross-platform compatibility, including sound via SDL_Mixer. This allowed Mad Bomber to expand rapidly—by 2003, it hit Windows; 2005 brought Amiga support; and further ports followed for GP2X (2006), Maemo and BeOS (2008), Palm OS (2008), Wii and Macintosh (2009), and even niche systems like MorphOS, RISC OS, and Atari ST.

Kendrick’s vision was preservationist: revive forgotten gems for a new audience without commercialization. As he noted in project documentation, the game aimed to “come as close as possible” to Kaboom!‘s feel, adapting its bomb-dropping frenzy to era-specific inputs like trackballs or joysticks. This context positioned Mad Bomber amid a wave of retro clones, like those in the Tucows archive, but its multi-platform reach (over a dozen systems) highlighted the democratizing power of open source. No AAA budgets here—just a solo dev’s passion, ensuring the game’s survival through community contributions, such as David Powell’s BeOS port.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

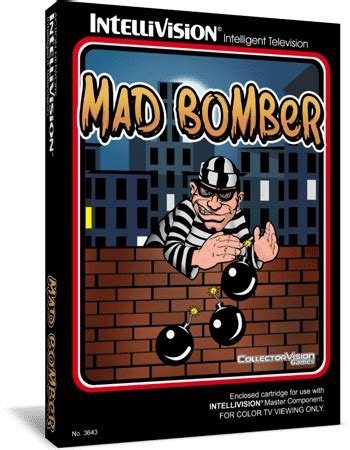

Mad Bomber eschews elaborate storytelling for the barest of premises, a hallmark of its arcade roots. The “narrative,” if it can be called that, unfolds in a single sentence from the official site: “The Mad Bomber is loose in the city and he’s dropping bombs everywhere! It’s your job to catch them before they hit the ground and explode.” This setup draws directly from Kaboom!, where the titular Mad Bomber—an escaped convict in striped prison garb—paces the rooftop, hurling explosives downward with gleeful malice. No cutscenes, no dialogue trees; the plot is emergent, told through gameplay.

At its core, the game’s “character” is the Mad Bomber himself, a perpetual frowner borrowed from Kaplan’s design. In Kaboom! ads, he taunts players with a Chicago-accented challenge: “So, you think you’re fast enough to beat the Bomber?” Mad Bomber inherits this archetype—a faceless terrorist embodying chaotic destruction for its own sake. The player, conversely, is an anonymous defender armed with water-filled buckets, symbolizing everyday heroism against anarchy. Themes revolve around vigilance and consequence: each missed bomb erodes your defenses (losing a bucket), mirroring real-world stakes where negligence leads to catastrophe. There’s no character progression or moral ambiguity; it’s pure binary—catch or perish.

Deeper analysis reveals subtle nods to ’80s gaming tropes. The Mad Bomber’s unlimited supply evokes Cold War-era fears of endless threats, while the buckets represent fragile human resilience. In two-player modes, cooperative play fosters teamwork against the villain, but competitive variants turn allies into rivals, exploring betrayal and rivalry. Dialogue is absent, but sound cues (bomb fuses hissing, splashes on success) narrate the tension. As a clone, Mad Bomber amplifies Kaboom!‘s thematic simplicity: in an age of narrative-heavy games like Final Fantasy VII (1997), it reminds us that stories can be implied through mechanics, not exposition. No villains’ backstory or redemption arcs—just unrelenting peril, making the Mad Bomber a timeless symbol of arcade antagonism.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Mad Bomber‘s core loop is a masterclass in minimalist design, distilling Kaboom!‘s reflex-testing frenzy into a fixed/flip-screen action experience. Players control a stack of three water buckets at the screen’s bottom, sliding them left-right via mouse, keyboard, or controller to intercept bombs dropped by the Mad Bomber from above. Bombs fall at varying speeds, requiring precise positioning; a catch douses the fuse with a satisfying splash, awarding points (scaling with difficulty). Miss one, and it explodes on impact, removing the bottom bucket—your lives visualized as a shrinking stack. Game over strikes at zero buckets or 999,999 points.

The systems build escalating tension through procedural generation. Bombs accelerate per level, with the Bomber’s pacing quickening and drop patterns randomizing for replayability. Early waves are forgiving, easing newcomers in, but later ones demand split-second reactions—mirroring Kaboom!‘s paddle precision but adapted for digital inputs. Difficulty settings (easy/normal) adjust fall speed, while the UI is spartan: a score counter, level indicator, and lives display dominate the top, with no HUD cluttering the action.

Innovations shine in multiplayer: single-player is solitary survival, but two-player modes offer co-op (shared buckets, alternating catches) and versus (one player as Bomber, dropping bombs to sabotage the other). This PvP twist, expanded from Kaboom!‘s Atari 5200/8-bit variants, adds social depth, turning quick sessions into heated rivalries. Character progression is absent—no upgrades or power-ups—but extra buckets award every 1,000 points (if lost), encouraging strategic misses near thresholds for a “reset” breather. Flaws? The direct control can feel finicky on some ports (e.g., keyboard lag on low-end hardware), and absent high-score tables limit persistence. Yet, these quirks enhance authenticity—SDL’s implementation ensures smooth 60 FPS on capable systems, with positional audio (left/right splashes panning) providing immersive feedback. Overall, the mechanics deconstruct arcade perfection: simple rules, infinite depth, proving why clones like this endure.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Mad Bomber‘s world is a minimalist urban nightmare—a static cityscape backdrop evoking Kaboom!‘s rooftop peril, but rendered in pixel art suitable for ’90s PCs. The setting is abstract: no sprawling metropolis, just a void bisected by the Bomber’s perch and your defensive line. This flip-screen simplicity builds claustrophobic tension; bombs cascade like an avalanche (nodding to its origins), heightening the sense of impending doom. Atmosphere thrives on implication—the Bomber’s shadowy silhouette against a starry sky conveys isolation, while explosions add fiery chaos without gore.

Visual direction is faithful yet enhanced: Kendrick’s sprites upgrade Kaboom!‘s blocky aesthetics with smoother animations and optional high-res modes. The Bomber’s perpetual scowl (smiling only on misses) injects personality, his prison stripes a visual motif of institutional escape. Buckets gleam with water effects, bombs fuse with glowing timers—subtle details that elevate the retro charm without overwhelming low-spec hardware. Ports vary: Amiga versions leverage chunky hardware sprites for vibrancy, while Palm OS shrinks to grayscale portability.

Sound design amplifies immersion via SDL_Mixer, featuring chiptune tracks that loop without fatigue—upbeat synths underscore urgency, avoiding the earworm pitfalls of lesser clones. Effects are the star: fuse hisses build dread, left/right catches pan spatially for directional cues, and explosions boom with cathartic finality. No voice acting, but the auditory palette (splashes, drops) creates a symphony of reflexes. These elements coalesce into a cohesive experience: visuals and sound don’t “build” a world so much as immerse you in eternal vigilance, where every tick-tock fuse reminds you of the stakes. In an era of bombastic audio like Quake III (1999), Mad Bomber‘s restraint contributes to its hypnotic pull, making failure feel visceral.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its 1999 Linux debut, Mad Bomber garnered niche acclaim in open-source circles, with sites like LinuxBerg rating it highly in arcade categories and user comments praising its addictiveness (“Very addictive game,” per reviews). Commercial reception was muted—no MobyScore due to its freeware status—but inclusions in Retro Gamer Magazine (#13 CD-ROM) and PC Magazine (Italian, 2002) exposed it to broader audiences. GameHippo.com awarded 8/10 in 2004, lauding its “professional” feel and multiplayer fun, while Maximum Linux (2000) noted it “comes as close as possible” to the original. User feedback was effusive: “Excellent rendition of a classic,” with Atari fans reminiscing about Kaboom! sessions. Criticisms were minor—some cited compilation issues in early versions—but overall, it scored A-grade for gameplay on Linux for Kids.

Commercially, as GPL freeware, success measured in downloads and ports rather than sales; Tucows archived it with a 4/5 rating, and it even featured in Virgin America Airlines’ in-flight “Red” system (2007-2018), reaching casual flyers. Reputation evolved from obscurity to cult status: post-2000 ports (e.g., Wii homebrew) kept it alive, influencing open-source remakes like Defendguin. Its legacy lies in preservation—grouping with “Avalanche variants” on MobyGames, it influenced indie arcade revivals and demonstrated SDL’s power for cross-platform games. While not industry-shaping like Kaboom! (which sold millions on Atari), Mad Bomber impacted education and accessibility, appearing in kids’ Linux distros and inspiring clones. Today, amid retro booms like Asteroids: Recharged, it underscores open source’s role in gaming history, ensuring Kaplan’s formula endures for new generations.

Conclusion

Mad Bomber is more than a clone—it’s a loving resurrection of Kaboom!‘s frantic joy, blending ’80s arcade purity with ’90s open-source ingenuity. From Kendrick’s solo vision to its sprawling ports, the game’s exhaustive mechanics, thematic simplicity, and evocative audio-visual restraint create an experience that’s deceptively profound in its minimalism. While lacking narrative depth or graphical fireworks, it excels as a reflex honed to perfection, with multiplayer adding communal spark. Reception affirms its niche triumph, and its legacy as a freeware bridge between eras cements its historical value. Verdict: Essential for retro enthusiasts and a testament to timeless design—8.5/10, a bomb worth defusing in video game history.