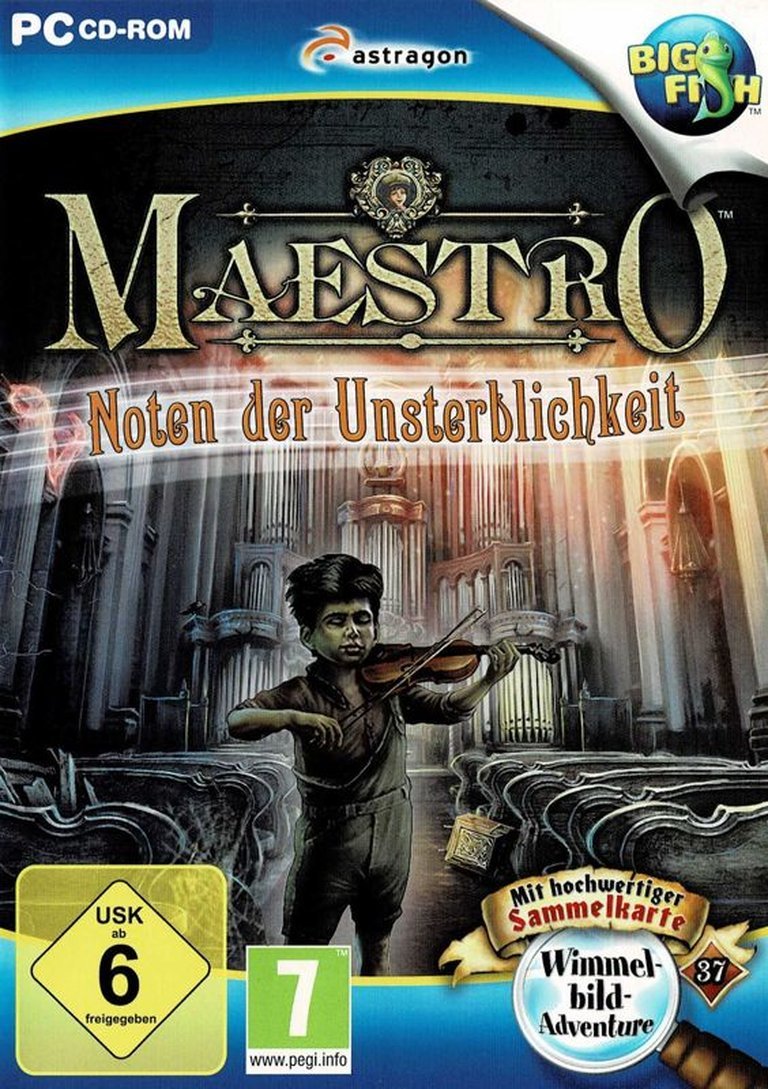

- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Big Fish Games, Inc.

- Developer: ERS G-Studio

- Genre: Adventure, Puzzle

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Mini-games, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 0/100

Description

Maestro: Notes of Life is a hidden object adventure game. As a detective you have to solve a new case. A girl has disappeared before her brother’s eyes. Apparently she was lured by a mysterious music — find the source of the music and, thus, the girl again. There are numerous hidden-object scenes and mini games to solve.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Maestro: Notes of Life

PC

Maestro: Notes of Life Guides & Walkthroughs

Maestro: Notes of Life Reviews & Reception

gamezebo.com : the developer is in serious danger of becoming the proverbial one trick pony.

hhogame.blogspot.com : Maestro: Notes of Life is no exception to being a great game as this sequel after Maestro: Music of Death takes the player to another dark musical ride with a new story, new scenarios, and creative puzzles that is certified to be loved by many.

Maestro: Notes of Life: Review

Introduction

In the shadowed corridors of interactive storytelling, few genres evoke as much nostalgic tension and intellectual engagement as the Hidden Object Adventure (HOA). Maestro: Notes of Life, a 2012 release from ERS Game Studios and Big Fish Games, stands as a quintessential entry in the Maestro series—a lineage defined by its marriage of musicality and macabre mystery. Here, the player assumes the role of a detective investigating the disappearance of a young girl, lured away by an insidious melody. As the second installment in the series following Music of Death (2011), the game inherits a legacy of atmospheric dread and intricate puzzles. Yet while its production values and narrative ambition are undeniable, Notes of Life exemplifies both the strengths and stagnation of the developer’s signature formula. This review dissects its execution through the lenses of history, mechanics, artistry, and legacy, arguing that despite its polished craftsmanship, the game ultimately underscores a creative plateau for ERS—a studio teetering on the edge of mastery and repetition.

Development History & Context

ERS Game Studios: Founded as a specialist in narrative-driven HOAs, ERS (also known as ERS G-Studio) carved a niche with dark, thematically rich titles like Dark Tales and Haunted Legends. By 2012, they were regarded as industry stalwarts, praised for meticulous art direction and reliable puzzle design.

Vision & Constraints: Notes of Life emerged during the genre’s commercial zenith, where digital distribution platforms like Big Fish Games dominated casual gaming. ERS’s vision was to refine their established template: a blend of detective noir, supernatural horror, and musical motifs. Technologically, the game adhered to era-standard conventions—2D flip-screen visuals, point-and-click interfaces, and CD-ROM distribution—prioritizing stability over innovation.

Market Landscape: Released alongside titles like PuppetShow and Redemption Cemetery, Notes of Life competed in a saturated market. Its success hinged on leveraging the Maestro series’ fanbase, who expected consistency in tone and structure. However, as critics would later note, this reliance on familiarity risked stifling evolution.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot Structure: The narrative unfolds through a classic detective framework: a missing person (the girl), a mysterious antagonist (Eva Kruger), and a trail of supernatural clues. The plot is segmented across six chapters, each unlocking new locales—from a cellar crypt to an underground chamber. While the premise is compelling—a girl stolen by “evil music”—execution leans heavily on cliché: Eva, a villain obsessed with eternal life, orchestrates abductions using a prodigious young musician as her pawn. The twist, revealing the prodigy as a victim rather than mastermind, feels underdeveloped.

Characters: The protagonist remains an enigmatic detective, a blank slate for player immersion. Eva Kruger, with her “bushy-haired sidekick,” embodies archetypal villainy: melodramatic, prone to vanishing monologues, and lacking nuance. Supporting characters (e.g., the imprisoned Alice) serve as quest triggers, their backstories sketched in journal entries rather than meaningful dialogue.

Themes: The central motif—music as a conduit for evil—is underexplored. While puzzles involve arranging notes and restoring instruments, the narrative fails to interrogate the psychological or philosophical implications of its premise. Themes of obsession and immortality are presented superficially, reducing Eva’s motivation to a one-dimensional quest for power. The game’s most intriguing theme—the seductive danger of art—remains latent, buried under procedural storytelling.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loops: Gameplay alternates between hidden object scenes (HOS), inventory-based puzzles, and mini-games. The HOS, while visually detailed, suffer from rote repetition: players scour cluttered environments for anachronistic items (e.g., corkscrews, doll heads) with little contextual logic. As one review noted, “who would think to give an apple to a squirrel to find a ribbon?”

Puzzle Design: Mini-games vary in creativity but rarely challenge. Musical puzzles—like reconstructing a violin or playing a xylophone—offer thematic resonance but lack depth. Others, such as rotating gears or aligning symbols, feel perfunctory. A standout puzzle involves arranging musical notes to match a diagram, yet its solution feels mechanical rather than intuitive.

Flaws & Innovations: The hint system is robust but generous, undermining tension. Inventory management is streamlined, with items auto-hiding to reduce clutter. However, the game’s greatest flaw is its linearity: solutions are often brute-forced through trial-and-error, discouraging lateral thinking. The “Collector’s Edition” bonus chapter adds little, repeating existing mechanics without fresh ideas.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Setting & Atmosphere: The game traverses a decaying fantasy world—a music academy overgrown with vines, a mist-shrouded park, and a subterranean laboratory. Each location drips with gothic grandeur, yet they feel interchangeable due to ERS’s signature “moody, candle-lit” aesthetic. As critics noted, crumbling structures and overgrown gardens recur across ERS titles, creating a sense of creative autopilot.

Art Direction: Visuals are exemplary for the genre—detailed illustrations, rich textures, and dynamic lighting. Characters are rendered with expressive grotesquerie, particularly Eva Kruger, whose design blends elegance and decay. However, asset reuse is glaring: HOS objects like corn cobs and axes appear regardless of locale, breaking immersion.

Sound Design: Music is the game’s namesake but its weakest element. Orchestral cues are serviceable but derivative, recycling motifs from earlier ERS titles. Sound effects—creaking doors, dripping water—are functional but unremarkable. The game misses an opportunity to leverage audio as a narrative tool, with the “evil music” reduced to background ambience rather than a character.

Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception: Notes of Life was a commercial success, buoyed by the Maestro series’ fanbase and Big Fish Games’ marketing. Critically, it garnered mixed-to-positive reviews. Gamezebo awarded it 70/100, praising its “exemplary graphics” and “hauntingly beautiful” atmosphere but lamenting its “solid-but-not-overly-innovative” gameplay. Adventure Gamers highlighted its “tricky puzzles” but noted a lack of originality.

Evolution of Reputation: Over time, the game is viewed as a microcosm of ERS’s broader trajectory—technically proficient but artistically stagnant. New players might enjoy its accessibility, but veterans recognize its formulaic structure. The Maestro series continued with Music from the Void (2013) and Dark Talent (2014), but none broke from the template established here.

Industry Influence: While Notes of Life didn’t revolutionize the HOA genre, it cemented ERS’s reputation as a reliable purveyor of dark, atmospheric experiences. Its legacy lies in its consistency: a benchmark for quality that simultaneously failed to innovate, reflecting the genre’s early 2010s stagnation.

Conclusion

Maestro: Notes of Life is a masterclass in execution but a cautionary tale in evolution. ERS Game Studios delivers a visually stunning, mechanically sound adventure that embraces the Maestro series’ strengths—moody atmosphere, intricate puzzles, and a compelling musical premise. Yet, its failure to transcend its formula—relying on recycled art assets, derivative storytelling, and perfunctory gameplay—underscores a critical inflection point for the developer. For fans of the genre, it remains a polished, if forgettable, entry. For history, it stands as a testament to the HOA’s golden age: a time when craft reigned supreme, but innovation was often sacrificed for familiarity. In the end, Notes of Life is not merely a game; it’s a reflection of an industry at a crossroads—one where excellence and risk-averse design walk a perilous line.