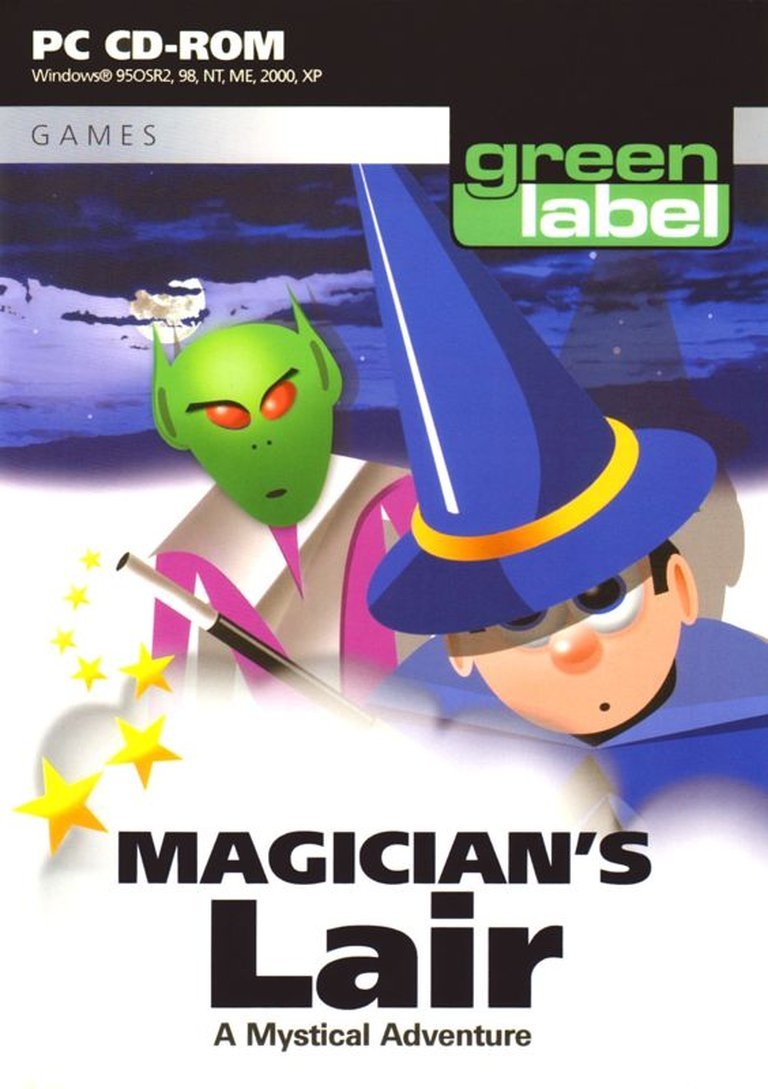

- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Greenstreet Software Ltd., Xing Interactive B.V.

- Developer: Illusion Software

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

Set in the year 1302, ‘Magician’s Lair’ plunges players into a fantasy world where an army of evil goblins has overrun their village, poisoned the land, and kidnapped the princess. As the hero, players must battle through hordes of goblins across multiple screens, utilizing power-ups with unpredictable effects—some beneficial, others harmful. A unique invisibility ability adds strategic depth, though using it obscures the player’s position on-screen. Notably, the game reuses assets from a demo included with ‘The Games Factory’ creation tool, offering arcade-style action within a fixed, diagonal-down perspective.

Gameplay Videos

Magician’s Lair Free Download

Magician’s Lair Cracks & Fixes

Magician’s Lair: A Cautionary Tale of Asset-Flipping and Forgotten Arcade Ambitions

Introduction

In the pantheon of early 2000s shovelware, Magician’s Lair (2004) stands as a stark monument to unfulfilled potential and recycled ambition. Developed by the obscure Illusion Software and published by Greenstreet Software/Xing Interactive, this Windows-exclusive action title arrived with negligible fanfare and departed with a whimper, accruing a dismal 1.2/5 player rating on MobyGames and vanishing into abandonware obscurity. This review dissects its troubled genesis, mechanical hollows, and non-existent legacy, arguing that Magician’s Lair epitomizes the era’s flood of low-effort, toolset-reliant curios—a game less remembered for its own merits than for what it represents about the industry’s underbelly.

Development History & Context

The Studio and Vision

Illusion Software remains an enigma, with Magician’s Lair as their sole documented release. The studio’s ambitions—if any existed—were hamstrung by their decision to base the game on Merlyn Lear’s 1996 demo project, included with Clickteam’s The Games Factory (TGF), a drag-and-drop game creation tool. This wasn’t iterative inspiration; it was near-total asset reuse, repackaged for commercial sale eight years later without meaningful innovation.

Technological and Market Landscape

By 2004, PC gaming was embracing 3D acceleration, open worlds, and narrative depth (Half-Life 2, World of Warcraft). Magician’s Lair, however, clung to mid-90s design sensibilities: fixed flip-screen stages, rudimentary sprites, and MIDI-backed audio (exclusive to its CD-ROM edition). Its release echoed a cottage industry of TGF-derived titles flooding bargain bins, capitalizing on casual players unaware of the game’s demo origins.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot and Characters

Set in 1302, the game’s premise is skeletal: evil goblins kidnap a princess and overrun a village. The unnamed protagonist—a wizard devoid of personality or backstory—must cleanse each screen of foes. There are no cutscenes, dialogue trees, or lore expansions. The narrative exists solely as a utilitarian vessel for arcade action, its feudal fantasy setting ripped from public-domain tropes.

Thematic Emptiness

Themes of heroism, sacrifice, or magic are absent. Even the titular “lair” feels misrepresented; levels lack environmental storytelling, reducing dungeons to bland grids. The goblins function as target practice, not antagonists with动机. It’s a thematic void, reflecting its origins as a tech demo rather than a crafted experience.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop and Combat

Magician’s Lair operates on a single-screen arcade template: clear enemies to progress. The hero moves via direct control, engaging foes with basic attacks. Two mechanics nominally distinguish it:

1. Power-Ups: Randomly spawned items offer buffs (e.g., damage boosts) or penalties (e.g., slowed movement). Their unpredictability injects RNG chaos but frustrates strategy.

2. Invisibility: A double-edged ability cloaks the player but hides their sprite entirely, rendering navigation guesswork—a novel idea marred by poor execution.

Progression and Flaws

Character progression is non-existent; no skill trees or equipment reward persistence. The game’s difficulty stems not from designed challenges but clunky controls and trial-and-error enemy placement. The UI is minimalist to a fault, lacking health bars or objective markers. With no save system and repetitive stage design, playthroughs devolve into monotony.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Aesthetics

The game’s visuals betray its TGF demo roots: recycled sprites, static backgrounds, and palette-swapped goblins dominate. Environments—villages, forests, caves—are interchangeable tilesets lacking detail. The fixed diagonal-down perspective feels archaic even for 2004, evoking early-90s fare like Gauntlet but without its charm.

Audio Design

The freeware version shipped sans music, while the CD edition added generic MIDI tracks—looping dungeon-lite melodies that amplify the tedium. Sound effects (sword clashes, goblin grunts) are serviceable but tinny, further anchoring the game in its low-budget origins.

Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception

Magician’s Lair garnered no professional reviews. Player feedback was sparse but brutal: its lone MobyGames rating (1.2/5) encapsulates its reputation. Critics of the era likely ignored it, while buyers felt misled by its retail price point (~$10–20) for a glorified demo.

Long-Term Impact

The game’s “legacy” lies only as a cautionary footnote:

– Asset-Flip Precedent: It foreshadowed modern Steam shovelware, showcasing how creation tools could be exploited for quick profit.

– Abandonware Cult Status: Preserved on sites like MyAbandonware, it’s now a curiosity for retro completists—a relic of how not to design a game.

Its sole innovation—the visibility trade-off—never inspired imitators, cementing its irrelevance.

Conclusion

Magician’s Lair is less a game than a archaeological oddity—a commercialized TGF demo masquerading as a retail product. Its failures are multifaceted: anemic narrative, repetitive gameplay, and a cynical disregard for player engagement. Yet, in its very cynicism, it offers historians a lens into early 2000s PC gaming’s unregulated underbelly, where tools like TGF enabled studios to peddle low-effort titles to unsuspecting audiences. For modern players, it’s a curiosity best experienced through scholarly interest rather than enjoyment. As art, it fails; as a historical artifact, it’s a poignant reminder that not all games deserve resurrection. Final Verdict: A 1.2/5 asterisk in gaming history—worthy only as a museum piece of industry exploitation.