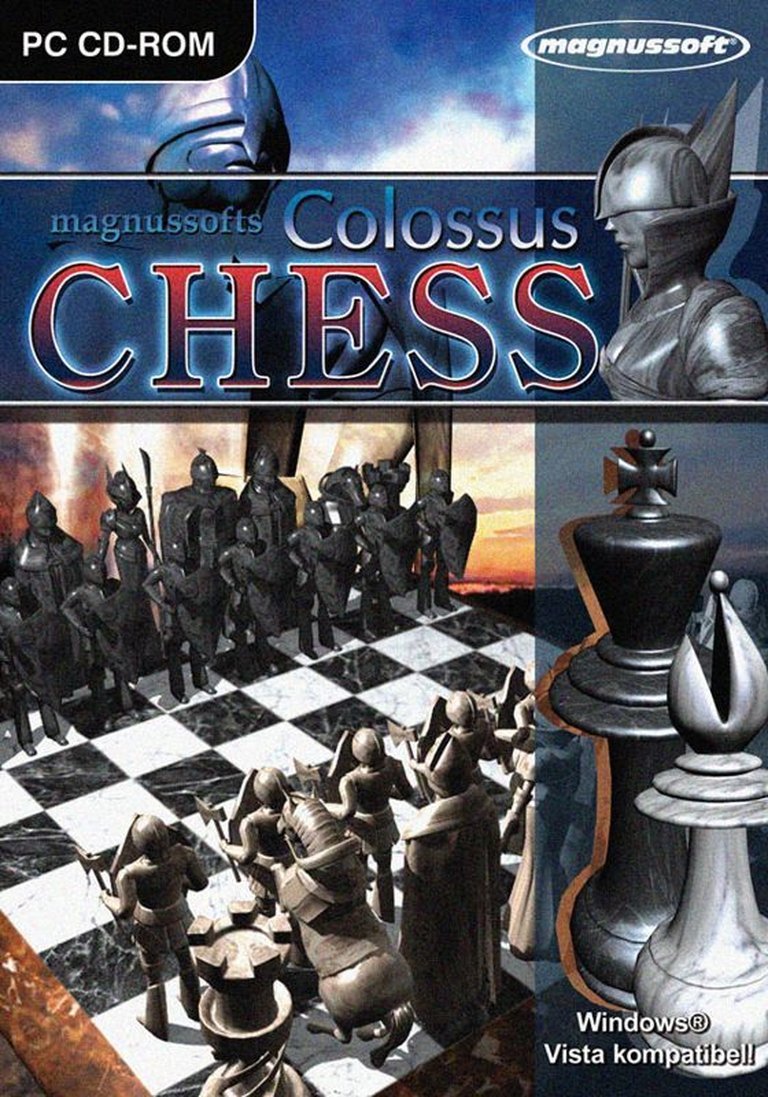

- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: magnussoft Deutschland GmbH

- Developer: magnussoft Deutschland GmbH

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Chess

Description

magnussoft’s Colossus Chess is a commercially released Windows chess game from 2007, part of the long-running Colossus series. It features high-quality, customizable 2D or 3D graphics, allowing players to change board textures, piece sets, and even import their own graphics during gameplay. The game offers a range of difficulty levels from beginner to professional, providing a polished and adaptable digital chess experience.

magnussofts Colossus Chess Reviews & Reception

talkchess.com : What makes me more happy personally is that new version does not crash when accessing tablebases on my Vista machine like 2006f did.

retro-replay.com : magnussofts Colossus Chess delivers a refined and customizable chess experience that caters to players of all skill levels.

magnussofts Colossus Chess: A Customizable Odyssey Through Digital Chess History

Introduction: The Enduring Allure of the Checkered Battlefield

Chess, in its pure form, is a timeless crucible of strategy and psychology. Yet, its digital translation has always been a fascinating study in adaptation—where the cold logic of algorithms meets the inexhaustible human desire for aesthetic expression. Into this arena steps magnussofts Colossus Chess, a 2007 Windows release from the German studio magnussoft Deutschland GmbH. At first glance, it appears as just another entry in the long-running Colossus series, a name that echoes through the annals of 1980s home computing. But this iteration is a distinct creature: a commercially packaged, graphically ambitious chess simulator that prioritizes player customization and visual fidelity above all else. This review will posit that while magnussofts Colossus Chess is a technically proficient and deeply customizable title, its historical significance is muted by its ambiguous lineage, niche market positioning, and the towering legacy of both its namesake and its contemporaries. It is a game that understands the visual hunger of the digital chess player but ultimately struggles to carve out a unique identity in a crowded and highly specialized field.

Development History & Context: Two Legacies, One Name

To understand magnussofts Colossus Chess (2007), one must first disentangle two parallel histories that share a moniker but little else.

The Original Colossus: Martin Bryant’s 8-Bit Legacy

The Colossus Chess name is synonymous with British programmer Martin Bryant. Beginning in 1983 as a development of his award-winning White Knight Mk 11 engine, Bryant’s Colossus Chess became a cornerstone of 1980s home computer chess. Released between 1984 and 1990 for platforms like the Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum, Atari ST, and Amiga, the series was renowned for its technical sophistication. Written in assembly language for each CPU, it pushed hardware limits: the ZX Spectrum version examined ~170 positions per second. It featured a full rules implementation (including underpromotion and the fifty-move rule), a 3,000-position opening book, and—revolutionarily for microcomputers—a 3D board view in Colossus Chess 4.0 (1985). Later ports (Colossus Chess X, 1988-1990) added enhanced graphics, four piece sets, and machine learning capabilities. Bryant’s creation was a critical and commercial success, becoming “one of the best selling chess programs of all time” and competing directly with giants like Chessmaster 2000. Its development effectively ceased in 1991, only to be resurrected decades later as the free, modern Colossus Chess UCI engine (2006 onward), which still competes in contemporary engine rankings (e.g., a 2694 Elo rating in KCEC 2013).

magnussoft’s Reinterpretation: A German Studio’s Vision

The 2007 magnussofts Colossus Chess exists in the shadow of this legacy but is a separate product. Developed and published by magnussoft Deutschland GmbH, a German studio with a portfolio encompassing casual games like Manga Solitaire and Die Pizzeria, this title is part of their own Colossus series, which previously included Colossus X Draughts (1993). The core team consisted of:

* Maik Heinzig: Idea and Project Management.

* Matthias Feind: Programming.

* Chie Kimoto: Graphics.

Released on August 20, 2007, for Windows as a commercial CD-ROM, the game arrived in a mid-2000s landscape dominated by a few key trends:

1. The Rise of 3D Interfaces: Following the visual spectacle of Battlechess and the sleek 3D boards in Chessmaster titles, there was an expectation for premium chess software to offer immersive visual options.

2. The Free Engine Revolution: Martin Bryant’s Colossus UCI was freely available, and other strong engines like Fruit, Rybka, and Crafty were open-source or free. A commercial chess game needed to justify its price with value-added features beyond a raw engine.

3. Niche Customization: The mid-2000s saw a rise in user-generated content and modding. magnussoft’s pitch—deep visual customization—tapped into this desire for personalization, offering tools to import custom graphics.

Thus, magnussofts Colossus Chess was not a continuation of Bryant’s engine work but a graphical shell and package built around an unspecified chess engine (likely a proprietary or licensed core), designed to sell on its aesthetic flexibility and user-friendly interface for the Windows casual-to-serious player.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story is the Game

As a pure abstract strategy game, magnussofts Colossus Chess possesses no traditional narrative, characters, or dialogue. Its “story” is the eternal one of chess itself: the clash of intellects, the drama of tactical fireworks, and the slow, inexorable pressure of positional advantage.

Emergent Narrative and Thematic Resonance

The game’s thematic core is explicitly player-centric emergence. There is no campaign, no historical scenarios, no AI personalities with backstories. Instead, every match generates its own micro-narrative. The opening is a prologue of familiar patterns; the midgame a tangled, chaotic middle act where plans are forged and broken; the endgame a tense, minimalist denouement where every pawn is a protagonist. The game tracks statistics and game logs, allowing players to retrospectively frame their sessions as a chronicle of improvement—from the blunder-filled tales of a beginner to the precise, layered sagas of a seasoned player.

The ability to import custom graphics for pieces and boards introduces a powerful layer of thematic identity. A player can transform the standard Staunton set into historical armies, fantasy creatures, or themed designs, thereby injecting external narrative directly into the visual representation of the conflict. Playing with “Medieval Knights” on a parchment-textured board changes the psychological and aesthetic experience, even if the underlying rules remain unchanged. This aligns with a broader gaming trend where customization is a form of self-expression and world-building, allowing the player to project their own narrative onto the abstract system.

Ultimately, the game’s theme is one of personal mastery and aesthetic ownership. It posits that the chess experience is not just about the algorithmic opponent but about the player’s relationship with the board itself—a customizable arena for their intellectual gladiatorial combat.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Depth Wrapped in Customization

The core of any chess software is its engine and interface. magnussofts Colossus Chess structures its gameplay around several key pillars.

The Engine and AI

The game offers multiple difficulty levels from “beginner” to “professional.” While the exact engine is not attributed in the sources, its calibration is noted as providing a “satisfying progression curve.” Casual players find accessible, forgiving opponents that teach fundamentals, while advanced players encounter opponents with “deeper tactical challenges” and improved endgame technique. This tiered approach is standard for commercial chess software aiming for a broad audience. Critically, the engine fully implements all standard chess rules, including complex ones like underpromotion and draw conditions (fifty-move rule, repetition, insufficient material), which was a notable feature in the original Colossus series and is maintained here.

User Interface and Customization (The Core Innovation)

This is where the game distinguishes itself. The interface is described as “intuitive” and “seamless,” allowing real-time adjustments:

* 2D/3D Board Toggle: Players can switch between a classic 2D view and a fully rendered 3D board with smooth animations, sculpted piece models, and dynamic lighting and shadows. The 3D mode aims for immersion, making pieces feel weighty and tangible.

* Three Distinct Piece Sets: Included are variations on the Staunton design, from classic to more avant-garde interpretations.

* Live Texture and Graphics Adjustment: The board’s material (wood grain, marble, metal) and piece textures can be tweaked during gameplay.

* Full Import System: The killer feature is the ability to import custom graphics for boards, textures, and entire piece sets. This turns the game into a chess board construction kit, fostering a creative community (as noted, “community… often shares downloadable packs”).

This system prioritizes aesthetic and experiential customization over deep analytical tools. There is no mention of opening books, engine analysis panels, or database management—features common in serious chess software like Chessbase or Chessmaster. The focus is on the presentation and immediacy of the match.

Gameplay Loop

The loop is straightforward: set up a game (time control, color, variant—though variants aren’t explicitly mentioned), choose your visual theme, and play. The AI adapts, and the game tracks statistics. The absence of a stated “problem-solving mode” or tutorials (despite “beginner” difficulty) suggests a lean design aimed at the player who already knows the rules and seeks a pleasant, customizable environment for play or practice.

Critical Assessment: The innovation is clear in the visual domain, but the gameplay systems are otherwise conventional. The lack of mention regarding pondering (thinking on opponent’s time) or opening book size (a key metric in the original series) suggests this is not an engine-focused product. Its “professional” difficulty, while calibrated, is unverified by modern engine rating lists (unlike Martin Bryant’s Colossus UCI which scores ~2700 Elo). For the serious student of the game, the toolset is likely insufficient. For the casual or aesthetically-driven player, it is more than adequate.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Virtual Chess Hall

Since the “world” is a chessboard, world-building equates to atmospheric and visual design.

Visual Direction

The game makes a strong case for itself here. The high-quality graphics are its headline feature. The 3D board is not a gimmick; it uses realistic rendering with attention to lighting and shadow to create depth. The three included piece sets offer stylistic range. The technical highlight is the dynamic texture system, allowing players to change board materials and piece appearances on the fly. The import functionality elevates this from a product to a platform, theoretically enabling infinite aesthetic variation. This focus on a “premium” look aligns with the mid-2000s trend of making classic board games feel luxurious and modern (Catan adaptations, Carcassonne 3D editions).

Sound Design

The source material is completely silent on sound. This is a glaring omission for a “high-quality” package. We can infer a standard implementation: perhaps subtle click sounds for moves, maybe a淡淡 background track. The lack of mention suggests sound was not a priority, a common trait in chess software where audio is often minimal or user-configurable. This is a missed opportunity to enhance immersion—imagine the satisfying clack of wood on a virtual table, or ambient sounds of a park or tournament hall.

Contribution to Experience

The art and sound (or lack thereof) directly serve the game’s thesis: the chessboard as a personal, aesthetic space. The visuals succeed in making the board feel like a tangible object, a digital heirloom you can customize. The silence, however, reinforces the game’s pure, contemplative nature. It is not trying to be a cinematic experience; it is a tool for focused thought, wrapped in a beautiful container. The atmosphere is one of quiet, intense concentration—a digital analogue to a well-appointed, tranquil study.

Reception & Legacy: A Niche Footnote

Contemporary Reception

Magnussofts Colossus Chess existed in a quiet corner of the market. There are no professional critic reviews aggregated on MobyGames, and no user reviews at all on the listed portals. The sole contemporary assessment comes from Retro Replay, which praised its “refined and customizable chess experience,” “intuitive interface,” and “graphical fidelity and flexibility,” ultimately calling it “a solid investment” for enthusiasts. This faint positive note suggests it met its modest goals for its target audience but failed to generate wider critical discourse.

Its commercial performance is obscure. MobyGames lists only 4 collectors (“Collected By”), indicating extremely low visibility. It was a CD-ROM release in an era rapidly moving to digital distribution (Steam launched in 2003), which may have hampered its reach.

Historical Context and Legacy

The game’s legacy is complicated by the naming collision with Martin Bryant’s seminal series. In the broader history of chess software, the Colossus name belongs to Bryant’s 8-bit and UCI engines. Magnussoft’s version is a derivative commercial product that leverages this heritage without contributing to its technical evolution. It did not influence engine development (its core is unheralded in engine tournaments) nor did it shape the graphical standards for chess software in a lasting way—Chessmaster and later Chess.com/Lichess clients would dominate that space.

Its primary legacy is as a curiosum of mid-2000s chess UI design: a game that bet heavily on 3D graphics and user customization as a value proposition for a commercial chess title in an era of free, superhuman engines. It represents a dead-end approach; today, the most successful chess applications (like Chess.com or Chessable) focus on cloud-based learning, massive databases, and online communities—not on local 3D board rendering. The dream of the beautiful, customizable desktop chess set was eclipsed by the utility of connected, analysis-rich platforms.

Conclusion: A Handsome, Forgotten Artifact

magnussofts Colossus Chess (2007) is a game of clear ambitions and muted impact. Developed by magnussoft Deutschland GmbH as a commercial Windows title, it successfully delivers a visually sophisticated and deeply customizable chess experience. Its strengths are undeniable: a genuinely useful import system for graphics, a smooth 2D/3D toggle, and an interface designed for aesthetic tinkering. For a player who views the chessboard as an extension of their personal style, it offers unparalleled freedom.

However, its weaknesses are equally apparent. It operates in the long shadow of the original Colossus Chess series’ technical legacy and the contemporary dominance of Chessmaster. It offers no analytical depth, no robust learning tools, and no online connectivity—features that would define the next decade of chess software. Its engine is unrated and unproven against the modern standard. Furthermore, the complete absence of sound design and any meaningful critical or community reception consigns it to a niche footnote.

In the grand tapestry of video game history, magnussofts Colossus Chess is a minor thread. It is not a lost classic, nor a flawed gem. It is a competent, aesthetically-focused product that arrived at the wrong moment, asking players to pay for visual customization in a world rapidly moving toward free, functionally superior digital chess ecosystems. Its fate is a lesson in market timing and product focus. For the historian, it is a snapshot of a specific design philosophy—that the beauty of the board is paramount—that ultimately could not compete against the rising value of data, community, and engine strength. For the enthusiast with a nostalgic eye for rendered wooden textures and 3D piece sets, it remains a pleasant, forgotten artifact. For everyone else, the game’s most enduring contribution is its name, forever linked to a more significant and influential chapter in the story of computer chess.