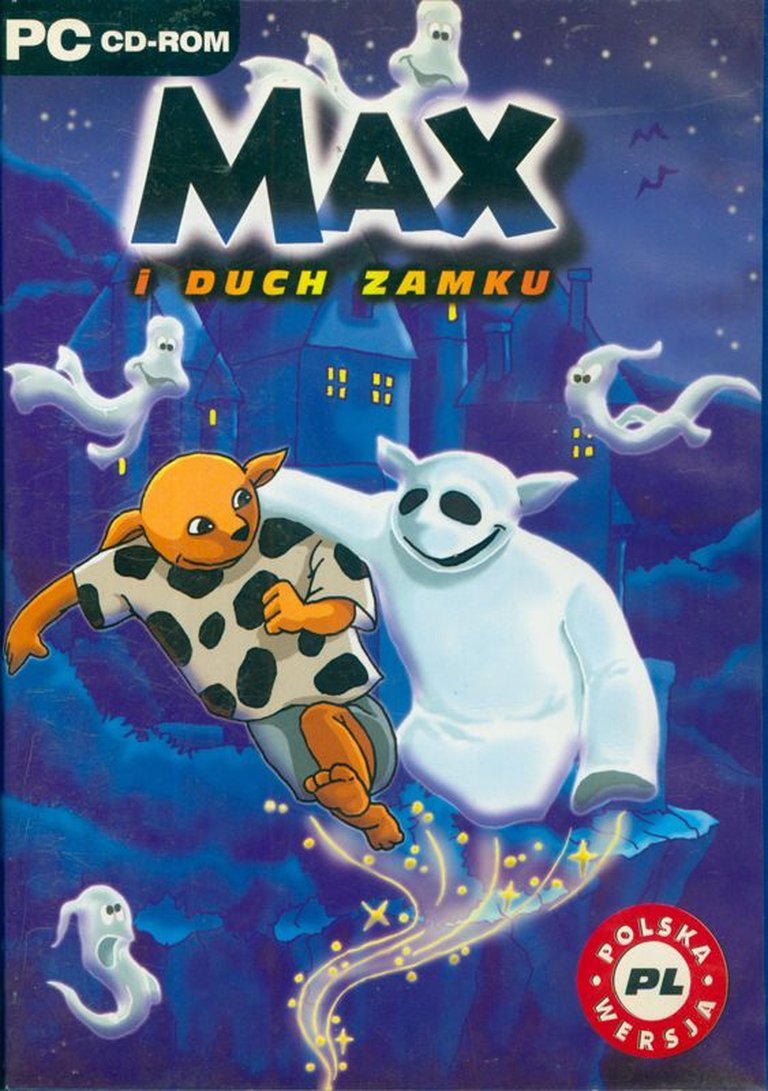

- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Publisher: Kursor Multimedia s.c., Tivola Electronic Publishing, Tivola Verlag GmbH

- Developer: Contor Interaktiv Multimedia Consulting & trading GmbH

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Fast travel, Fixed screen, Flip-screen, Point and click

- Setting: Haunted castle, Village

Description

Max and the Haunted Castle is a point-and-click adventure game for children, featuring the lovable dog Max from a quaint village who embarks on a whimsical mission to rescue Willy, a friendly ghost trapped in a haunted castle due to his hunger. Willy’s only sustenance—holey yellow socks—must be collected throughout the castle’s many rooms, each filled with interactive, comical animations and dialogue. Players guide Max through the fixed-screen environments, collecting all the hidden socks to help Willy regain his ghostly strength and escape. Offering humor, exploration, and accessible gameplay, the game is available in multiple languages and includes fast travel for seamless room-to-room navigation, making it an engaging and lighthearted introduction to adventure gaming for young players.

Gameplay Videos

Max and the Haunted Castle Free Download

Max and the Haunted Castle: Review

1. Introduction: A Forgotten Gem in the Twilight of Educational Point-and-Click Adventures

Imagine a haunted castle where the greatest threat to the friendly ghost isn’t a demonic conjurer, a failed exorcism, or even darkness—but hunger. Specifically, the hunger for holey yellow socks. This bizarre, whimsical premise lies at the heart of Max and the Haunted Castle (2000), a German-developed, Tivola-published point-and-click adventure aimed squarely at children. Yet beneath its ostensibly silly exterior lies a surprisingly rich artifact of early 2000s educational gaming, a game that exemplifies both the poetic absurdity and pedagogical sincerity of European children’s interactive storytelling at the turn of the millennium.

Max and the Haunted Castle is not a groundbreaking technical achievement by the standards of its time—nor was it designed to be. Instead, it is a meticulously crafted, artistically coherent, and narratively self-contained experience that thrives on tone, character, and environmental play. As one of the early entries in Tivola’s Max series, it bridges the gap between 90s edutainment (think Putt-Putt, Freddi Fish) and the more European-inflected, stylistically bold kids’ games of the early 2000s (such as Sam & Max Hit the Road in spirit, if not in technical ambition).

My thesis is this: Max and the Haunted Castle is a culturally significant micro-masterpiece of early children’s interactive storytelling—a game whose narrative absurdity masks a deeply humane, thematically resonant commentary on innocence, compassion, and the performative nature of fear, all wrapped in a technically competent, visually charming, and mechanically accessible package. While it received near-zero critical attention at launch, it has quietly evolved into a belated cult artifact, remembered through fragmented nostalgia and preserved through scattered fan communities and game archival efforts. This review will unpack how a game about a dog collecting smelly socks for a starving ghost became a subtle meditation on empathy, absurdity, and the enduring charm of childhood logic.

2. Development History & Context: The Birth of a Yellow-Socked Angel

2.1 The Studio: Contor Interaktiv – German Edutainment’s Quiet Innovators

Developed by Contor Interaktiv Multimedia Consulting & Trading GmbH, a German multimedia outfit based in Hamburg, Max and the Haunted Castle emerges from a distinct European tradition of child-centric, pedagogically informed game design—a tradition largely absent in the more action- or combat-oriented children’s games of the North American market at the time. Contor Interaktiv was no flash-in-the-pan studio; they specialized in interactive learning tools, children’s adventure games, and animated educational software, often publishing under the Tivola brand (Tivola Electronic Publishing, Tivola Verlag GmbH), known for its gentle tone and strong artistic direction.

Contor’s projects—such as Snow White and the Seven Hansels, Oscar the Balloonist Drops into the Countryside, and earlier entries in the Max series—reflect a European aesthetic: softer, more narrative-driven, less reliant on challenge, and more focused on environmental exploration, dialogue, and character interaction. This pedigree is critical: Max and the Haunted Castle is not a game designed to be “won” quickly or efficiently. It is designed to be experienced, with humor, curiosity, and mild wonder as its guiding principles.

2.2 The Vision: Absurdity as Pedagogy

The creative vision was led by Barbara Landbeck, whose dual role as author and illustrator underscores the game’s tightly integrated aesthetic. With 42 credited individuals—a remarkably large team for a modestly scoped children’s title—Contor assembled a multinational, multilingual team reflecting the game’s European identity: Polish voice talent (Iwona Kowalska, Katarzyna Bujakiewicz), German animation (Dirk Seefeld, Silke Weiland), Hamburg-based sound production (Hastings Music Hamburg GmbH), and Polish sound engineering (Studio Nagrań EXE – Szczecin).

This international collaboration was essential to Tivola’s mission: to create pan-European children’s media. The game launched with German, English, and French language support—a rarity for the time, especially for educational software—demonstrating Tivola’s foresight in creating culturally portable content. The use of Hans Paetsch (a beloved German narrator known for his storytelling) alongside Colin Solman (an English voice actor with prolific credits in video game narration) speaks to this dual-audience approach.

2.3 Technological Constraints & Design Choices in 2000

Released in 2000 on Windows 16-bit and Macintosh, with a later 2002 Windows release, Max and the Haunted Castle was developed during a transitional period in PC gaming. The industry was shifting from 16-bit to 32-bit systems, and adventure games were undergoing a crisis (with The Longest Journey about to revolutionize the genre in 1999, and LucasArts having ceased development on new titles). In this context, a fixed-screen, point-and-click, flip-screen adventure was already considered a retro design choice—yet it was the perfect fit for its audience.

Why? Because children aged 4–10 don’t need AI pathfinding, 3D graphics, or complex save systems. They need immediate feedback, clear affordances, and visual cues. The flip-screen perspective—where each room loads with a “snap”—ensures that the environment is always legible, reducing cognitive load. The point-and-select interface, with clickable hotspots providing animations or dialogue, aligns with mouse-based learning, a core tenet of early 2000s educational software.

The game even includes a fast travel button—a rare convenience feature. This isn’t gamer pandering; it’s pedagogical consideration. A child searching for socks might get frustrated; allowing them to teleport between rooms maintains engagement without sacrificing progression. It’s a design nod to the attention span realities of its audience.

2.4 The Gaming Landscape: A Tale of Two Markets

In 2000, the gaming world was dominated by massive AAA titles (EverQuest, The Sims, Unreal Tournament, Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2). Meanwhile, the children’s market was increasingly fragmented: the PlayStation offered Spyro, Crash Bandicoot, and Tombi!; the PC offered The ClueFinders, Reader Rabbit, and Clifford the Big Red Dog. What set Tivola’s games apart was their European humor, cartoon art style, and lack of gamification violence.

Max and the Haunted Castle exists in a niche with titles like Pajama Sam, Putt-Putt, and Carmen Sandiego: Word Detective, but it is more artistically ambitious than many of its contemporaries. The animations are hand-crafted, the voice acting is consistent and expressive (with multiple actors for a single character across languages), and the world feels lived-in, even if fictional.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absurdity of Need

3.1 A Premise So Silly It’s Genius

The plot is deceptively simple: Willy, a friendly ghost, is trapped in a room because he’s too hungry to float through walls. His hunger is for holey yellow socks. Max, a cheerful dog, must collect all the socks in the castle to free him.

On the surface, this is pure absurdism—Kafka meets Pedigree. But beneath the giggles lies a surprisingly rich thematic core. The premise mirrors the reality of invisible needs. Willy isn’t trapped by iron bars or spellwork; he’s trapped by hunger, a mundane, human condition, rendered in ghostly terms. The “trap” is not physical but physiological and emotional: a creature of the afterlife reduced to basic biological dependency.

The choice of holey yellow socks as sustenance is not arbitrary. Socks are domestic, personal, and slightly ridiculous. They are associated with comfort, homeliness, and childlike humor (think “smelly gym socks”). By making this the ghost’s lifeblood, the game demystifies the supernatural—the ghost is not terrifying, but pathetic, even relatable. He’s not a force of nature; he’s a guy who needs a snack.

3.2 Max: The Unlikely Hero of Compassion

Max is not a warrior, scholar, or detective. He’s a dog—a symbol of loyalty, innocence, and unconditional love. In children’s media, dogs often serve as moral compasses, guiding players toward empathy. Here, Max’s motivation is not glory or reward, but altruism: “Willy is stuck. I must help.”

This is crucial. The game teaches not just problem-solving, but prosocial behavior. Max doesn’t earn the socks; he finds them, often by interacting with characters who are also quirky and harmless (e.g., a vampiric bat who collects lint, a narcissist clock who loves compliments). No one is the enemy. The “adventure” is not a quest for power, but for community understanding.

Max’s journey reflects Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory: children learn through social interaction and imaginative play. Every click triggers dialogue, humor, or animation—mini-stories that model how to interact with others, not defeat them.

3.3 Willy: The Ghost as Comic Pathos

Willy is not just a plot device; he’s a character study in absurd vulnerability. He is a ghost, yet he cannot float because he is hungry. He is supernatural, yet bound by physical laws of absurdity. He is trapped, but his prison is not dark or scary—it’s a room with a chair and a window.

The game’s comedy arises from this clash: the ghost trope (haunted castle, moaning spirits, cobwebs) is subverted by domestic banality. The horror is replaced with bathos. When Max finally frees Willy, there is no dramatic release, no explosion of energy—just a sigh of relief and a thank-you. The emotional peak is quiet, not triumphant.

This aligns with Bakhtin’s concept of carnivalesque: the down-low of the supernatural through humor and irony. The castle, expected to be terrifying, becomes a playground of curiosity. The scariest thing? A sock under a pillow.

3.4 The Castle as a Rorschach for Fear (and Laughter)

The haunted castle is a meta-commentary on genre expectations. Every trope is present—moats, secret passages, night-vision goggles (as a joke), a vampiress bat, a mad scientist’s lab—but none are used to frighten. Instead, they are inviting absurdities.

- The vampire bat Clara doesn’t drink blood; she collects lint.

- The mad scientist Gustaw doesn’t create monsters; he experiments with cheese.

- The ghost butler Fabian doesn’t haunt; he obsesses over dusting.

These characters perform their stereotypes (“Ah, I am Klara the bat! I live in darkness!”) but subvert them (“But also, I love knitting!”). This self-aware humor is accessible to adults while being non-threatening to children. It teaches critical consumption of media—the idea that stories can be silly, arbitrary, or joyfully illogical.

The rescue of Willy becomes a rejection of fear. By approaching the castle with curiosity, not terror, Max models emotional resilience. The theme is clear: scary things become safe when you understand them.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Pedagogy of Play

4.1 Core Gameplay Loop: Exploration, Interaction, Collection

The core loop is simple but effective:

- Explore a room by clicking on objects.

- Interact to trigger animations, dialogue, or minigames.

- Collect yellow socks (hidden in obscure or funny places).

- Progress to new rooms until all socks are found.

- Return to Willy to complete the story.

Each room is a self-contained puzzle box, with multiple interaction points. Clicking on a portrait might cause it to sag in syrup; clicking on a fireplace might make logs hop; clicking on a cat might start a song.

This behavioral feedback is key. Every click yields a reaction—positive reinforcement for exploration. It’s not trial-and-error; it’s playful discovery.

4.2 The Sock System: Collection Without Pressure

The heart of the game is the sock count. Socks are hidden in:

- Obvious places (under rugs, in drawers)

- Absurd places (inside cheese experiments, under vampire’s knitting)

- Humorous places (on a statue’s nose, in a moat’s fish mouth)

Crucially, no sock is truly hidden. There are no “pixel hunts”; every sock is associated with an interactive object. This avoids frustration and maintains flow state. The fast travel system compounds this: if a player gets stuck, they can move forward and return later.

The game never penalizes failure. There are no lives, no timers, no consequences. It is a no-pressure environment—a stark contrast to most games, even children’s titles.

4.3 UI & Accessibility

The UI is minimal: a status bar with collected socks, a fast travel button, and a spoken narrator (optional). The point-and-select interface uses visual cues (glowing spots, tooltips) to indicate interactivity. The cursor changes when over a hotspot, a standard but essential feature.

Language support is seamless. Players can switch between German, English, and French via the menu, with voice and text synchronized. This flexibility is rare, even today, and speaks to Tivola’s commitment to accessibility and inclusion.

4.4 Systems: Innovative in Their Own Way

- Fast Travel Button: A stroke of genius. Reduces backtracking without breaking immersion.

- Girl Power Mini-Game (in polish version?): Rumored but unconfirmed—possibly a distractable cop in early builds. Not present in final versions.

- Reactive Environment: Every click yields entertainment, not just progression. This makes the castle feel alive, not just maze-like.

- No Combat or Threats: A deliberate choice. The only “danger” is a dropped sock.

Flaw: The lack of save system (or it being obscure) can frustrate modern players. However, for its intended audience—short session play (15–30 minutes)—this is less critical.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: A Cartoon Cathedral of Whimsy

5.1 Visual Direction: Hand-Drawn Whimsy

Barbara Landbeck’s hand-drawn, cartoon art style is the visual soul of the game. The art is European cartoon—think French Astérix, Polish Jacek, German Clever & Smart—with soft lines, exaggerated proportions, and warm colors. The castle is not gothic or foreboding, but invitingly cluttered: portraits with googly eyes, chandeliers that wobble, staircases that defy physics.

Each room is a vignette of absurd domestic life:

– The Lab: full of bubbling cheese and singing test tubes.

– The Library: with books that talk and a clock that demands praise.

– The Kitchen: where the butler needs a snack before being helpful.

The animation, done by Kai Pahl, Dirk Seefeld, and others, is hand-crafted and expressive. Characters don’t just move—they perform, with squash-and-stretch, timing, and personality-driven motion. When Klara the bat flutters, she flutters with a diva’s flair.

5.2 Sound Design & Music: A Symphony of Silliness

The sound design is layered and intentional:

– Ambient: faint moans, creaking doors, ticking clocks—used sparingly, for tone, not terror.

– UI Sounds: cheerful chimes, comical boings, whooshes when scrolling.

– Character Audio: distinct voices, with consistent vocal direction (Jens Busch, Harald Schnitzler).

The music, composed by Harry Gutowski (©ED. Harry Nova), is lighthearted and melodic, with a peppy tune for Max’s theme and eerie-yet-funny motifs for the castle. The score never overwhelms; it enhances but never dominates.

5.3 The Haunted Castle Reimagined

The ghost trope is reinterpreted as adolescent-scale fantasy. The “haunted” elements—moats, towers, secret doors—are features of play, not fear. The cobwebs? Laundry. The ghosts? Just dude who likes socks.

This reclamation of horror tropes for innocence echoes The Spiderwick Chronicles or Coraline—but ten years before them. It’s a proto-kids horror-comedy, with The Haunted House or Donald Duck and the Haunted House as ancestors, but with 21st-century digital warmth.

6. Reception & Legacy: Forgotten, Then Rediscovered

6.1 Launch Reception: Silence from the Critics

At launch, Max and the Haunted Castle received no major reviews. MobyGames, SockesCap64, and LaunchBox list it with zero critic scores, few user ratings, and no mainstream media coverage. This is not surprising: it was a niche educational German import, bundled with children’s magazines (e.g., bundled with CyberMycha in Poland in 2002).

In the Classroom/EdTech Sphere (if it entered schools at all), it may have been used as a introductory PC interaction tool, but it lacks the direct curriculum ties of Reader Rabbit or Scholastic’s Magic School Bus.

6.2 Commercial Performance & Distribution

Distributed in Germany, the UK, France, and Poland, it likely saw modest sales, with the 2002 Windows release in Poland being its most accessible Western version. The 2010 Russian compilation Zabavnye pohozhdenija Maksa: 3v1 (“Max’s Fun Adventures: 3 in 1”) suggests it had Eastern European appeal, possibly for its slapstick humor and retelling of European fairy tales.

6.3 Cult Revival: Nostalgia and Archival Interest

The game’s legacy has grown posthumously:

– Reddit threads (e.g., r/nostalgia, 2018) ask, “Does anyone remember Max…?”

– GOOG’s Dreamlist has 52 registered fans hoping for a re-release.

– MobyGames lists it with 5 collectors—a sign of niche reverence.

– Discussion in forums centers on “Where can I play it?” and “Was the lab cheese real?”

It has influenced no direct successors, but its tone echoes in later titles:

– The humor in Sam & Max: Season One (2007) — absurdism without malice.

– The art style of Tails of Terra or Little Wing (2023) — hand-drawn European design.

– The pedagogy of Cranky Cat (2020) — curiosity-driven interaction.

It may have inspired the use of the haunted house as a joyful space, a trend now seen in Spiritfarer, Gris, and Hollow Knight: Silksong.

Despite no direct awards, its 42-person team, international production, and commitment to joy make it a cultural artifact of European edutainment.

7. Conclusion: The Ghost of Game Design’s Soul

Max and the Haunted Castle is not a great game by technical metrics—it lacks 3D graphics, AI, or mainstream recognition. But by emotional, artistic, and pedagogical standards, it is exceptional.

It reminds us that games don’t need difficulty, challenge, or violence to be meaningful. A game can be about a dog collecting socks for a hungry ghost—and still teach empathy, exploration, and the joy of the absurd.

In an era of hyper-finished, hyper-expensive AAA titles, Max and the Haunted Castle stands as a testament to quiet innovation: a game where the achievement isn’t a trophy, but a smile.

Its legacy is not in sales or sequels, but in the ghost of its innocence—a fleeting memory for some, a rediscovered joy for others. It is, in the truest sense, a haunted castle of the soul: scary on the outside, utterly sweet on the inside.

Final Verdict:

★★★★☆ (4/5) —

Not a masterpiece of gameplay depth, but a microscopic marvel of tone, art, and heart. A must-play for gaming historians, educators, and anyone who remembers the joy of clicking on something just to see what happens.

Historic Place:

Max and the Haunted Castle deserves recognition as a crucial link in the evolution of children’s interactive storytelling—a bridge between 90s edutainment and the more emotionally intelligent, visually rich, and humorously daring games of the 2020s. It is, quietly, a ghost with a sock for a soul—and we are all the warmer for having met it.