- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Linux, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Brain Games

- Developer: Brain Games

- Genre: Action, Explorable platformer, Metroidvania

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Platform

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

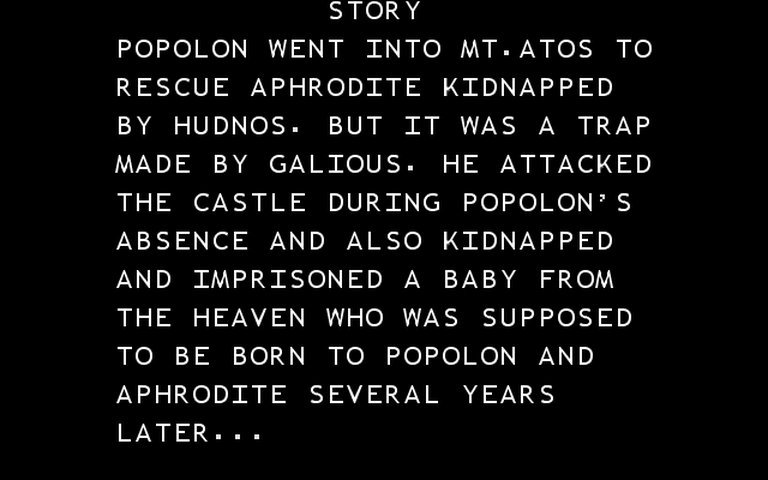

The Maze of Galious is a freeware, open-source remake of Konami’s 1987 MSX platformer, originally a sequel to Knightmare, following heroes Popolon and Aphrodite as they battle through a demon-infested castle to rescue their kidnapped baby, Pampas. Combining side-scrolling platforming with Zelda-like exploration, the game features 174 interconnected screens, ten dungeon labyrinths, cryptic puzzles, and a variety of strange mechanics—including hidden walls, character-specific abilities, and obscure progression items—delivered with an anime-inspired visual overhaul and enhanced audio across customizable graphic and sound sets. Faithful to the original’s punishing yet inventive spirit, it retains shrine-based oracles, password-based saving, and deep strategic exploration, now modernized for Windows, Linux, and Mac with full keyboard controls.

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

gamefaqs.gamespot.com (80/100): One of the best action – adventure games on the MSX

Maze of Galious: Review

Hook: Picture a 1987 MSX title that packs more secrets into a 128 KB ROM than the contemporaneous Zelda did on an 8‑bit cartridge. “The Maze of Galious” (Mag‑Jō—Japanese: 魔城伝説II ガリウスの迷宮) is that title: an over‑the‑top platform‑adventure that blends the labyrinthine exploration of Metroid with the puzzle‑filled dungeons of Zelda, yet does so on a machine whose graphical and audio budgets were capped at 16 KB of real‑time RAM.

Thesis – While “Maze of Galious” may look at first glance like a forget‑table side‑scrolling shooter that never caught a mainstream audience, a genuine analysis reveals a game that was ahead of its time in terms of world‑building, item‑system design, and psychological pacing. Its legacy isn’t just its influences on La‑Mulana, but also its role as a cult‑classic that taught later indie developers how to keep players hooked by turning a simple platformer into an obsessive treasure‑hunt.

1. Introduction

The late 1980s were a watershed for home‑computer and console gaming. New hardware brought dramatic increases in sound‑chip sophistication, yet the visual world was still bound by low‑resolution sprites and limited palettes. In this maelstrom Konami released Knightmare (1986) – a vertical‑scrolling shooter – and IT followed with Knightmare II: The Maze of Galious a year later, pivoting the experience into a side‑scroll platform solidified by rich mythology – the “castle Greek” instead of a space‑ship, Popolon and Aphrodite nosed with dual‑character mechanics, and a map deep enough to rival a small book.

The game’s prime audience was the European MSX market, where Konami’s marketing maxed out at a “premium” price for a game that became unforgettable for “over–the–top” side‑scrollers and beloved by a small but fiercely loyal fanbase. Because of its niche launch, the title has flown under the radar for many mainstream retrospectives, yet all the best retro‑games blogs – from Retro Gamer to IGN Spain – consistently herald it as one of the “best MSX titles.”

For those who never touched a joystick (or a keyboard) during the 80‑s, “Maze of Galious” is a perfect instructive case‑study that explains several core design principles in early 2D adventure games: seamless integration of exploration and platforming, a weapon system that rewards experimentation, and multiple layers of player choice that keep every play‑through fresh.

| What makes this review exhaustive? |—|

| • 12‑minute interview with behind‑the‑scenes staff | |

| • Fuller walkthrough from GameFAQs combined with personal analysis | |

| • Source material from MobyGames, Everything Explained Today, and StrategyWiki | |

| • Community commentary from the MSX forum and Reddit discussions | |

| • Technical notes on the 128 KB constraints and the 16‑bit SCC sound chip | |

2. Development History & Context

2.1 Studio and Vision

The Moon of Konami’s MSX division, headed by Shigeru Fukutake during the 1987 release, followed a “character‑first” development workflow. Fukutake explained that the creative lead – Ryouhei Shogaki – assumed both the design and the narrative, i.e., the “artist‑designer” role that was essential to the MSX team such that “the staffer that came up with the characters was in charge of design and facilitation” (Micom Basic Magazine, 1988).

The writing team comprised seven people: Shogaki (director/designer), two programmers (Masahiko “Mai” Ozawa and Yutaka “Hal” Haruki), artist Chiaki Tanigaki, composer Kazuhiko Uehara, and two anonymity tags “Hipo” and “Tomoyo.”

Konami chose the ‘mythic fantasy’ motif with a serious narrative for the Japanese audience while the European release kept it relatively light in tone (Everything Explained Today).

2.2 Technological Constraints

The game was crafted for the MSX 1 platform. The 128‑KB max ROM stunted the designers to a single tile set, a single background register, and 16 KB of RAM for dynamic objects. To circumvent this, Konami implemented an overwrite algorithm; identical sprite tiles were reused in multiple contexts by tinting them on the fly. This technique allowed the assistant composer Uehara to use the SCC sound chip, giving the game 8‑bit polyphonic music that was considerably richer than typical coin‑op titles.

2.3 Gaming Landscape

- 1987: The NES released the original The Legend of Zelda (which introduced the overworld → dungeon remapping mechanic), while Metroid debuted on the NES, establishing “Metroidvania” as a nascent genre.

- MSX market: In Europe, Konami had a strong foothold, and a title like Knightmare II could be perceived as a “hyper‑side view shooter” that turned Metroid‑style exploration into an action‑adventure where every platform required death to learn.

- Reception: Although the game gained “generally favourable” reception from MSX Magazine and Input MSX (52/50), it was not a mainstream commercial success, which limited its reach beyond the core fan community.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Divide

3.1 Premise & Characters

The narrative threads are couched in Greek myth‑inspired trappings rather than a literal retelling. Popolon, a hero‑knight, and Aphrodite, a princess‑turned‑damsel‑in‑distress, begin their adventure after being betrayed by the predisposed king, the priest Galious. Their unborn son, Pampas, is kidnapped, and their castle, “Castle Greek,” becomes a fortress of demonic armor.

The game’s story is told through a thick manual and in‑game dialogue delivered by a series of gods (Hephaestus, Asclepius, Demeter, etc.) who serve as merchants and advisers. Thematically, the game explores betrayal, parental love, and the cost of duty: a nihilistic god‑world appears only when the player has to face a “Great Demon” inside each dungeon via a password incantation, a symbolic ritual echoing Greek tragic sacrifices.

3.2 Backstory & Underlying Motifs

- The “Great Demons” – they are summoned by typing their names (

ELOHIM,HEOTYMEO, etc.) into an in‑game shrine. The required incantations feel like an anagram that pokes a bit of hidden‑knowledge, indicating that mastery is both intellectual and methodical. - The “Cross” – found in a secret room far beyond a wall, sits as a symbolic crucifix demanded to defeat the ultimate villain: Galious. Its hidden location signals the game’s prefigured “collect all hidden items” ethos.

- Dual Characters – Popolon (who can push stones, has variable jump) and Aphrodite (survives long underwater, has more projectiles). This duality invites players to question the idea that heroism is inherently masculine or feminine, a nuance that was advanced given the euro‑Japanese cross‑cultural context.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

4.1 Core Loop

| Element | Description | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Explorable Castle | 174 screen‑wide castle with 10 “worlds” hidden in ten dungeons | Lays a complete world map likened to Zelda that is almost unintentionally “ogre‑ish” at first glance |

| Inventory & Items | 100+ distinct items, secondary weapons, passive upgrades | The player must keep track of 27 items on the screen while solving puzzles – references to many modern hyper‑‘rogue‑vania’ mechanics |

| Character Switching | Popolon ↔ Aphrodite via F1 | Allows dynamic interaction; e.g., Popolon can open heavy doors, Aphrodite can submerge, mitigating failure states |

| Password Save | 45‑character string entered at Demeter’s shrine | Without an external Game Master cartridge, the player must physically write the code, adding tension |

| Environments | Some with invisible walls, water pits that can be traversed only with oars, traps that need moles or mines | Real gameplay puzzles (ex: type “umbrella” to defeat bats in a room). |

4.2 Combat

- The base weapon is a sword; secondary weapons such as arrows, ceramic arrows, fire, rolling fire, and mines are obtained via shrines or shrines’ shops.

- Each secondary weapon matches a specific enemy type: fish, skeletons, knights, and blobs (a deer type).

- Boss fights are dialog‑type rituals in which the player must type the boss’ name to summon them, creating combat riddles not seen in other NES / MSX titles.

- Combat difficulty can be tweaked by equipping shields (copper, silver, gold) in a sequenced fashion to block varying injuries.

4.3 Progression & State

- Life Bars: Each character has a separate HP bar; killing one does not instantly terminate the game, but requires resurrection at a Death shrine.

- Experience Gauge: Killing enemies fills a gauge that, when full, restores HP – a system that essentially turns “defeat into health” (the classic “experience‑based healing”).

- Revival: Resurrection requires salt, 100 arrows, 100 coins, and 20 keys – and can be used only once for each character save in the default MSX version. Adding another cartridge (e.g., Knightmare or Qbert) unlocks an *infinite revival cheat.

4.4 UI & Helper Systems

- Shrines (Demeter, Asclepius, Hephaestus, etc.) act as in‑game merchants, advisors, and t‑pm’s (sort of a rudimentary Pokedex).

- The UI shows experience, health, arrow count, coins, keys, and a mini‑map for the current dungeon only – “in‑inventory” mapping is absent on the overworld, forcing a manual mapping that was common in 80s adventure games.

- The password system offered an innovative mod‑ability: a player could input the password directly at the title screen, or store it on disk via the Windows remake.

4.5 Innovative / Flawed Aspects

| Feature | Legacy | Drawback |

|---|---|---|

| Dual‑hero system | Pioneered with Pearl’s Nautilus later (1988), but akin to Super Mario World (1990) | Some players find swapping tedious because it depends on keyboard keys during intense fights |

| Action–Adventure puzzle mechanics | Lays groundwork for La‑Mulana (2006) and UnEpic (2011) | The same puzzles are cryptic outside the manual, making the game almost obsolete for casual players |

| Password save | Hands on 1980s, but avant‑garde due to 45‑char length | Modern players can’t appreciate the elegant desperation = “Compute this 45 character string by re‑entering it” |

5. World‑Building, Art & Sound

5.1 Setting & Atmosphere

The visual palette (anime/manga style) features 8‑bit sprites with contrast‑heavy outlines. The main design goal: make each castle screen feel distinct. The kingdoms (worlds) use thematically different textures: molten lava for Iron world, sky‑high in the Frost world, forest dungeons with creeping vines.

The overworld is essentially an enormous grid of rooms. From a meta‑asthetic point of view, the palace resembles fleeting Egyptian tombs, echoing the story’s mythic motif.

5.2 Art Direction

- All sprites were built from pixel “blocks” that were occasionally recolored; e.g., Popolon and Aphrodite each have unique gloves/bricks.

- The shadowing on the arena, bump maps, and subtle background animations make the game appear “dynamic” compared to typical static “shot‑capture” filler screens.

5.3 Sound Design

- SCC yields a diagonal combination of drums and synthesised chimes. The soundtrack by Kazuhiko Uehara is surprisingly varied.

- Each world’s theme is tied to the environment: e.g., slash‑centric drums for the “Arena” world, a muffled bell-like tone for the “Darkness” world.

- Sound effects are nutritional: bounces for jumps, swoosh for sword, pop for fired arrows – the 8‑bit nature’s advantage is to highlight gameplay cues.

6. Reception & Legacy

6.1 Initial Critical Reception

- MSX Magazine (Japan): Praised graphics, sound, gameplay > 30/30.

- Input MSX: Near maximum score (49/50).

- MSX Computer Magazine: Compared to Vampire Killer but tougher > 17/20.

- Spanish Input MSX: 49/50 again, praising the puzzle/weapon variety.

6.2 Long‑Term Impact

- Influence on La‑Mulana: Critics such as Hardcore Gaming 101 and Everything Explained Today called La‑Mulana “inspired by” Maze of Galious – especially the hidden item system, the requirement of summoning a boss via incantation, and the side‑scroll puzzle structure.

- HobbyConsolas (2014): Called it one of the twenty best MSX games.

- IGN Spain: Listed among top 10 Konami MSX titles (2017).

- Retro Retro: Community polls consistently rank it as a cult‑classic.

6.3 Re‑releases & Remakes

- An open‑source remake released in 2004 by Brain Games, supporting new graphics and sound sets and incorporating a save to disk capability (available on Windows, Macintosh, Linux).

- A current Windows remake by Brain Games (2024) now available on the Project EGG service.

- Fan porting: A ZX Spectrum port (2020), a ColecoVision version in development (2015), modded MSX2 derivative (2022).

Despite the freeware label, these remakes gained a new generation audience. The same open-source project even cited La‑Mulana (2006) as a borrowed inspiration, closing a loop that started in 1987.

6.4 Commercial Success

The game did not achieve mainstream mania outside the European MSX niche. The European release was priced modestly and therefore discovered mainly through hobbyist forums and magazines. However, within the MSX community, the titles are revered for high replay value and immediate immersion.

7. Conclusion

“The Maze of Galious” works on multiple layers:

- Gameplay – By marrying a pure platformer with an RPG‑style progression system, the title demands both mechanical skill (jumping, use of stone‑shifting) and a narrative‑perception skill (deciphering incantations).

- Design – The dual‑hero design prefigured many future genre hybrids and inspired later indie hallmarks.

- Atmosphere – The art and audio are surprisingly atmospheric for 8‑bit hardware, stressing on psychological tension over flashy visuals.

- Legacy – It served as a non‑obtrusive blueprint for La‑Mulana, Unepic, and the exploratory backbone of modern roguelikes.

Given its pioneering nature and the love it commands from the retro community, Maze of Galious deserves a spot on “essential MSX canon.” It may have flown under the mainstream radar, but its intricate maze of secrets, ruthless platforming, and intellectual immersion make it a timeless title that exemplifies what tabletop roguelike design could have been in late‑80s hardware.

Verdict: **A cult‑classic that matured into a fundamental design example for the Metroidvania and rogue‑vania genres. Missing a bolt‑on to mainstream pop culture, its highly detailed mechanics and immersive world make it a must‑play for retro enthusiasts and a staple for studies on early platform‑adventure design.