- Release Year: 1984

- Platforms: Antstream, Arcade, MSX, NES, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, SG-1000, Sharp X68000, Wii, Windows

- Publisher: Hamster Corporation, Hudson Soft Company, Ltd., Koei Tecmo Games Co., Ltd., Micomsoft, SEGA Enterprises Ltd., Tecmo, Inc., Tehkan Ltd., Video Ware, Inc.

- Developer: Tehkan Ltd.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 58/100

Description

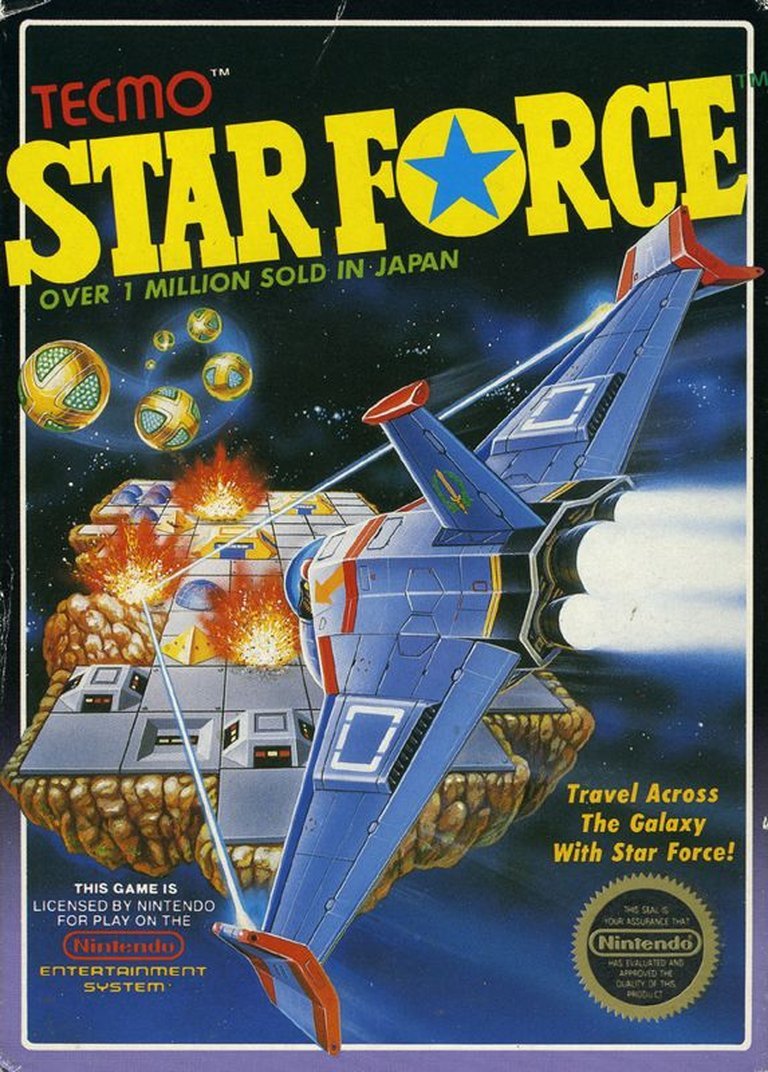

Megaforce (also known as Star Force) is a top-down, 2D scrolling sci-fi shooter where players pilot a spaceship to destroy enemy aircraft and ground targets across levels named after the Greek alphabet. Collect special letter symbols for bonuses and power-ups, then defeat challenging bosses at the end of each area to advance.

Megaforce Mods

Megaforce: Review

Introduction

In the pantheon of 1980s arcade and console shooters, few titles embody the raw, unfiltered essence of the genre like Megaforce (released internationally as Star Force). Born from the fertile grounds of Japan’s arcade boom and later ported across multiple platforms, this vertically scrolling shooter from Tehkan (precursor to Tecmo) represents a pivotal—if often overlooked—moment in shoot ’em up history. Its stripped-down mechanics, relentless difficulty, and minimalist design stand in stark contrast to the genre’s later evolution into sprawling epics. Yet, Megaforce remains a fascinating artifact, a testament to the era’s experimental spirit and a foundational piece for developers like Hudson Soft. This review argues that while Megaforce may lack the depth or polish of its successors, its influence on the genre’s design principles and its role in popularizing high-score competition cement its significance as a historical touchstone—a game whose flaws are inseparable from its charm.

Development History & Context

Megaforce emerged in 1984 from Tehkan, a studio carving its niche in the competitive arcade landscape. The development team, led by Shinichi Sakamoto (“Cheabow”) and Seiji Matsunaga (“Matsu”), operated under the technological constraints of early 1980s arcade hardware. Vertical scrolling shooters were still in their infancy; games like Xevious (1983) had defined the template, but Megaforce pushed it toward pure, unadorned action. The game’s core vision was simplicity: a lone starship battling waves of alien craft across stages named after Greek letters, emphasizing reflexes over narrative.

The arcade release in September 1984 was modestly successful, ranking as the 14th highest-earning table arcade unit in Japan that November. This traction prompted rapid ports. Hudson Soft handled the 1985 Famicom version in Japan, leveraging its newly launched “Caravan Festival”—a nationwide high-score competition—to drive sales. Hudson’s strategy proved prescient; events like these became synonymous with the company’s identity. Conversely, the North American NES port (published by Tecmo in 1987) deviated significantly. As composer Keiji Yamagishi noted, the NES version was a “separate” creation, altering controls, music, and gameplay difficulty. The SG-1000 port by Sega highlighted the platform’s limitations, with choppy scrolling and inferior audio compared to the Famicom. This fragmentation—across arcades, consoles, and computers—reflects the era’s chaotic porting practices, where regional adaptations often overshadowed the original design.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Megaforce’s narrative is a cipher, a byproduct of its arcade origins. Players pilot the “Final Star,” a sleek spacecraft, through an unnamed war against faceless alien forces. There are no cutscenes, dialogue, or character arcs—only the cyclical progression from Alpha to Omega, followed by an “Infinity” stage. This abstraction is intentional: the game’s narrative is one of pure survival. Bosses are designated by Greek letters (Alpha, Beta, etc.), transforming stage-clearance into a ritualistic sequence. The lack of lore forces players to project their own stories onto the pixelated clashes, framing each stage as a chapter in an eternal cosmic struggle.

Themes of escalation and repetition dominate. The Greek alphabet stages imply a structured, almost mythic progression, mirroring classical epics. Yet, the “Infinity” loop after Omega exposes the futility—yet addictive lure—of endless battle. This duality captures the genre’s ethos: the pursuit of mastery over insurmountable odds. Critics like The Video Game Den argue that Megaforce’s “raw and brutal” design aligns with its true purpose: not storytelling, but the pursuit of high scores. In this, it prefigures modern “bullet hell” shooters, where narrative serves as a backdrop for mechanical rigor.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Megaforce is a study in refined minimalism. Players control the Final Star with an 8-way joystick and a single fire button, navigating vertically scrolling fields filled with enemy spacecraft, ground turrets, and colossal bosses. The combat system is deceptively simple: a primary laser that upgrades in power when players collect letter symbols (F-I-N-A-L). Each collected letter enhances the shot’s spread and damage, incentivizing risk-taking to secure power-ups. However, the system has only two power levels, a stark contrast to later shooters offering missile barrages or screen-clearing bombs. This limitation forces players to master evasion over firepower, heightening tension.

Progression relies on pattern recognition and split-second reflexes. Stages are unforgiving, with enemies spawning in relentless waves. Notably, a bug in the Japanese Famicom version allowed players to halt enemy spawning by ceasing fire—a “feature” Tecmo’s NES port “fixed,” increasing difficulty. This exemplifies how regional adaptations could fundamentally alter gameplay. The NES version also slowed ship response time and accelerated enemy bullets, a change Questicle.net derides as “turning one of my favorite 8-bit shooters into a solid, but deeply flawed title.” Despite these quirks, the core loop—shoot, dodge, collect, survive—remains compelling. The high-score focus, where initials are appended to Greek-letter bosses, transforms each play into a personal duel.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Megaforce’s world is rendered in bold, functional abstraction. The arcade version features floating islands dotted with enemy structures, suggesting a battle across a shattered alien landscape. Environments shift subtly between stages, using color palettes to denote mood—Alpha’s blues imply cold, distant space, while Omega’s fiery reds signal apocalyptic conflict. The NES port, however, simplifies backgrounds into monochrome voids, focusing resources on sprite designs. Enemy craft are geometric and menacing, from darting fighters to colossal, multi-segmented bosses. The Final Star itself is a sleek, arrow-like vessel, its pixel-art detail limited by hardware but iconic in silhouette.

Sound design underscores the game’s austerity. Arcade blips and blops convey gunfire and explosions, while the Famicom’s chiptune soundtrack offers jaunty, militaristic melodies. The NES version’s audio, however, drew criticism from Nintendo Life as a “further irritant,” with harsh percussion that grated during extended play. This audio-visual dichotomy highlights how Megaforce’s presentation evolved: arcade cabinets embraced its aesthetic clarity, while home ports sacrificed charm for technical constraints. Together, these elements create a distinct atmosphere—one of isolated heroism in a vast, hostile cosmos, amplified by the game’s unyielding pace.

Reception & Legacy

Megaforce’s reception at launch was commercially buoyant in Japan but critically muted. The arcade version’s success belied a lukewarm critical response, with later retrospectives like All Game Guide dismissing it as “exhausting” and “overwhelming.” Home ports fared better in niche circles. The SG-1000 version earned a 91% from The Video Game Critic, praising its “simplicity and challenge,” while the Famicom’s high-score focus garnered cult respect. However, the NES version’s aggressive difficulty drew ire: Eurogamer noted it was “smooth and fast and enjoyable enough” but felt “out of place” on the Wii Virtual Console amid superior shooters. Nintendo Life awarded it a 4/10, calling it a “reference piece” but lacking “long-term appeal.”

Over time, Megaforce’s legacy shifted from competitor to historical artifact. Its influence is subtle but profound: Hudson Soft’s Star Soldier (1986) directly evolved its mechanics, while the Caravan Festival popularized high-score culture. Ports on platforms like the X68000 (1993) and Wii Virtual Console (2009) introduced it to new generations, often framed as a “classic” rather than a contemporary masterpiece. Modern releases via Hamster’s Arcade Archives series (2015–2018) recontextualize it, with Nintendo Life’s Dave Frear calling it “mediocre and unoriginal” yet undeniably foundational. Today, it stands as a cautionary tale of ambition vs. execution—a game whose difficulty and repetition alienated players but whose purity inspired genre titans like Gradius.

Conclusion

Megaforce is a game of paradoxes: a foundational shooter yet a flawed relic, a commercial success yet a critical footnote. Its minimalist design, born from arcade-era constraints, stripped the genre to its essence—pure, unadulterated challenge—while its Greek-letter stages and “Infinity” loop presaged the bullet hell obsession with pattern mastery. Ports like the NES version highlight how regional adaptations could warp a game’s soul, yet the core vision of high-score combat endures. While later shooters would expand its vocabulary with secondary weapons and elaborate narratives, Megaforce remains a vital link in the genre’s evolution. Its legacy is not in perfection, but in proof: that a game’s place in history is secured not by bells and whistles, but by the purity of its ambition. For historians and shmup enthusiasts alike, Megaforce is less a destination than a milestone—a testament to the era’s bold, brutal, and unforgettable experiments in electronic combat.