- Release Year: 1982

- Platforms: Antstream, Arcade, Atari 2600, Atari 8-bit, Atari ST, Browser, NES, Plex Arcade, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Atari Corporation, Atari, Inc., Atari Interactive, Inc., HAL America Inc., HAL Laboratory, Inc., Microsoft Corporation, TOPICS Entertainment, Inc.

- Developer: Atari, Inc.

- Genre: Action, Fixed-screen shoot ’em up

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Action, Arcade, Shooter

- Setting: Garden, Mushroom forest

- Average Score: 67/100

Description

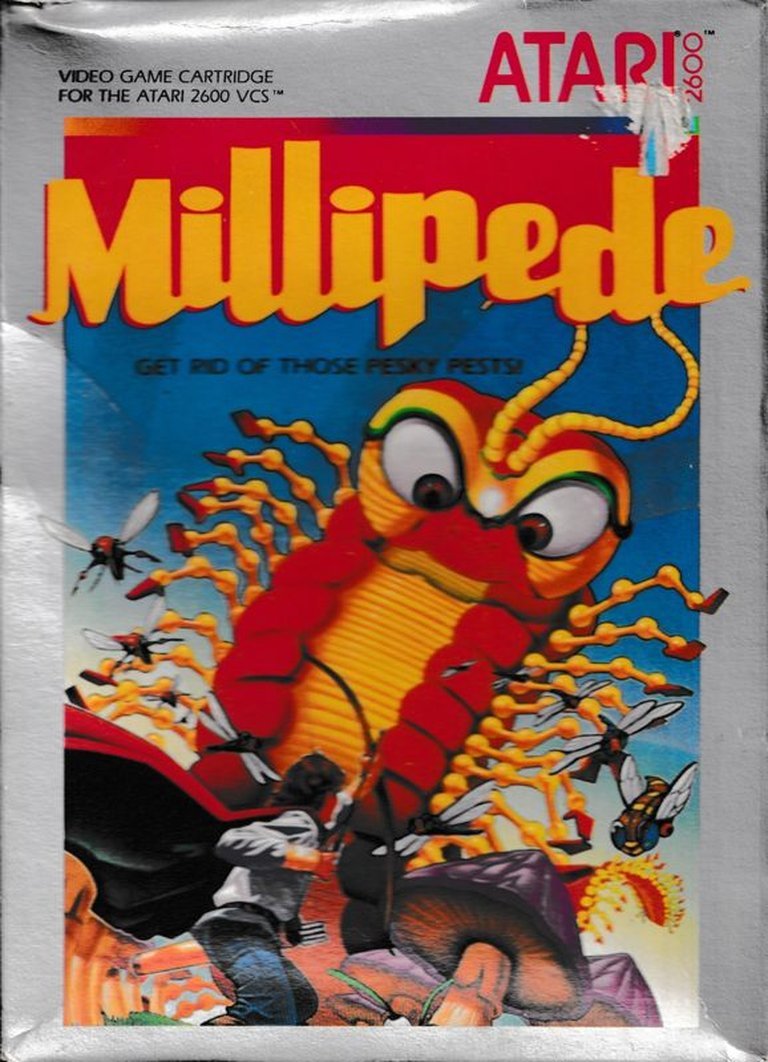

Millipede is a sequel to the classic arcade game Centipede, set in a garden overrun by a swarm of insects including millipedes, spiders, bees, dragonflies, and earwigs. Players control a bug zapper to shoot arrows at these creatures, aiming to destroy the multi-segmented millipede as it traverses through mushroom forests toward the bottom of the screen. Progressively difficult levels challenge players to eliminate all millipede segments while dealing with additional enemies and strategically timed DDT bombs that can destroy multiple insects at once.

Gameplay Videos

Millipede Free Download

Millipede Guides & Walkthroughs

Millipede Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (67/100): I’m seeing jerkiness and slower speed.

Millipede Cheats & Codes

NES

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| SUKGETVI | Both players have infinite lives |

| PAVKSPGA | Player 1 starts with 1 life |

| ZAVKSPGE | Player 1 starts with 10 lives |

| ASESIIEZ | Increase territory to half screen |

| AXESIIEZ | Increase territory to full screen |

| NKESIIEZ | Shrink territory |

| ZEUSXYTE | Player’s bullets move faster |

| LEUSXYTA | Player’s bullets move slower |

| NAVKSPGA | Player 1 starts with 255 lives |

| AEUSNPPA | Invincible |

| AENIPYPA | Invincible |

| AASIEPPA | Invincible |

| 0066:05 | Infinite Lives P1 |

| 0071:00 | Invincible |

| 0025:99 0026:99 0027:99 | Max Score P1 |

| 0021:99 0022:99 0023:99 | Max Top Score |

| 002F:?? | Round Modifier |

Millipede: Review

Introduction

In the glittering, high-score-driven era of the early 1980s, when arcades pulsed with the digital heartbeats of Pac-Man and Donkey Kong, Atari unleashed a sequel that dared to escalate chaos into art: Millipede. Released in November 1982 as the follow-up to the genre-defining Centipede, this fixed-shooter transformed a simple garden defense into a symphony of insectoid mayhem. While it never quite reached the cultural zenith of its predecessor, Millipede carved its own legacy through ruthless mechanical precision, diabolical enemy design, and an almost balletic level of screen-filling dread. This review dissects not just a game, but a microcosm of Atari’s ambition—a title where every millipede segment, every DDT explosion, and every mushroom’s death throes represents a masterclass in distilled arcade fury. Our thesis: Millipede is a sophisticated refinement of the shoot-’em-up blueprint, a title whose brilliance lies in its escalating complexity and unapologetic difficulty, yet one whose legacy remains perpetually eclipsed by the shadow of its iconic forerunner.

Development History & Context

Millipede emerged from the fertile soil of Atari’s golden age, designed by industry luminary Ed Logg (uncredited in the final release) and programmed with contributions from Mark Cerny, who devised the game’s innovative mushroom-growth algorithm—a system mimicking Conway’s Game of Life. The project was a calculated response to arcade operators’ concerns about Centipede’s diminishing profitability due to expert players mastering its strategies. Atari’s vision was clear: create a sequel that retained the original’s accessibility but layered on punishing complexity to extend playtimes and coin drops. Technologically, the arcade unit ran on MOS Technology’s M6502 processor clocked at 1.512 MHz, supporting 32 colors and a distinctive trackball controller—a tactile upgrade from Centipede’s joystick, enabling fluid, rapid-fire maneuvering. This choice underscored Atari’s commitment to precision, though it constrained home ports. Released during the industry’s 1982 peak—when titles like Dig Dug and Pole Position dominated—Millipede faced the unique challenge of balancing arcade expectations with the looming console revolution. As Atari phased out the Atari 2600 (the game’s eventual 1984 home port) in favor of the 5200 (whose Millipede port was famously cancelled), the title became a relic of a transitional era, its development a testament to Atari’s relentless, yet sometimes shortsighted, innovation.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative, drawn from the game’s arcade flyer, is a Shakespearean tragedy in miniature. Players assume the role of Archer, a royal elf who rejects his dying father’s crown, choosing instead to defend a lush mushroom forest against a curse unleashed by his father’s vengeful spirit. This backstory transforms the game into an allegory of responsibility versus idealism: Archer’s love for nature (represented by the mushrooms) clashes with the wrathful chaos of oversized insects. The millipede itself is a symbol of unstoppable entropy, its segmented body a metaphor for fragmentation and decay. Dialogue is sparse, limited to on-screen text (“GAME OVER,” “CONTINUE?”) and sound cues, but the narrative thrives through environmental storytelling: poisoned mushrooms (tinted purple) represent corruption; indestructible flowers (created by ladybugs) symbolize irreversible change; and the DDT bombs—a nod to the real-world pesticide—serve as tools of ecological destruction. Thematically, Millipede explores the futility of control: Archer’s arrows can never fully reclaim his garden, as mushrooms regrow, enemies multiply, and the screen perpetually scrolls. It’s a darkly whimsical meditation on humanity’s struggle against nature’s chaos, where every victory is temporary and every loss resets the battlefield.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Millipede’s core loop is a masterclass in escalating tension: the Archer, confined to the bottom fifth of the screen, fires arrows upward to destroy a millipede snaking through a mushroom forest, while evading or neutralizing a menagerie of insects. Unlike Centipede, the millipede moves faster, splits into smaller segments when shot (each spawning a new head), and accelerates as it descends. The game introduces seven new enemies, each with unique behaviors:

– Earwigs poison mushrooms, forcing the millipede to plummet vertically.

– Bees drop mushrooms vertically and require two hits to destroy.

– Spiders (now appearing in multiples) bounce erratically, devouring mushrooms.

– Inchworms slow all enemies when shot—a crucial respite.

– Ladybugs transform mushrooms into indestructible flowers.

– Dragonflies zigzag, leaving mushroom trails.

– Mosquitoes bounce diagonally, scrolling the screen upward when hit.

DDT bombs add strategic depth: triggered by a single shot, they obliterate enemies and mushrooms within a radius, with destroyed enemies worth triple points. The mushroom field undergoes periodic “growth” phases governed by cellular automata rules, creating unpredictable terrain. Players can start at advanced levels (e.g., beginning with 30,000 points), but difficulty scales mercilessly: by level 20, three spiders can overwhelm the screen. The scoring system rewards precision—spiders yield more points when shot near the Archer—and grants extra lives at milestones (e.g., 15,000 points). Yet, these mechanics expose the game’s brutality: a single misstep can erase progress, and bonus rounds (swarms of bees/dragonflies) offer fleeting high scores but demand near-perfect execution. The result is a gameplay loop of meticulous strategy and reflexive panic, where every shot is a calculated risk.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Millipede’s world is a Boschian nightmare rendered in vibrant 32-color arcade graphics. The mushroom forest serves as both battlefield and ecosystem, with mushrooms acting as terrain, obstacles, and targets. Visual design is functional yet evocative: the millipede’s segmented body undulates with eerie smoothness, while spiders skitter with jagged, unpredictable paths. The Atari 2600 port, praised for its technical wizardry, simplifies sprites into distinct shapes (e.g., rectangles for mushrooms), but the arcade version’s enemies are instantly recognizable—earwigs scuttle with segmented legs, dragonflies dart like blue needles. The Archer, a bow-wielding figure at the screen’s base, anchors the player’s perspective, while the DDT bombs pulse like toxic hearts. Sound design is equally critical: each enemy emits a unique auditory cue—bees buzz, spiders skitter, explosions roar—allowing players to identify threats by ear alone. The trackball’s tactile feedback enhances immersion, translating digital chaos into physical sensation. Yet, the atmosphere is one of impending doom: the screen’s downward scrolling, the constant hum of enemies, and the mushroom’s regrowth create a sense of inevitable overrun. It’s a world where beauty (the forest) and horror (the insects) are inseparable, reflecting the game’s core theme of nature’s duality.

Reception & Legacy

Millipede was a commercial triumph in arcades, ranking as Cash Box’s fourth-highest-grossing game of 1983, trailing only Ms. Pac-Man, Pole Position, and Dragon’s Lair. Critics lauded its intensity and variety, with Atari Times awarding the arcade and Atari 2600 ports a 95% score, praising its “frantic gaming action” and faithfulness to the original. Woodgrain Wonderland noted the inchworm’s slow-time mechanic as a “huge difference” in the chaotic gameplay. However, home ports faced mixed receptions. The Atari 8-bit version was criticized for choppy animation (Video Game Critic: “awfully choppy!”), while the NES port drew ire for its reduced screen size (All Game Guide: “inexcusably small playfield”) and lack of trackball precision (Ultimate Nintendo: “cheap deaths”). Players celebrated its replayability—scoring systems and bonus levels encouraged repeated plays—but lamented difficulty spikes (NES Archives: “spiders make this game near impossible”). Culturally, Millipede appeared in films like Joysticks (1983) and Arthur 2: On the Rocks (1988), cementing its arcade-icon status. Its legacy endures through compilations like Atari Anthology (2005) and Atari Vault (2016), and it remains a staple of retro tournaments. Yet, it never surpassed Centipede in cultural impact—a victim of its own refinement, where innovation bred complexity rather than mass appeal. As historian James Hague notes, it exemplified Atari’s early-80s ethos: “technical brilliance with a hint of desperation.”

Conclusion

Millipede is more than a sequel; it is a symphony of controlled chaos, a game where every millipede segment, every DDT blast, and every mushroom’s regeneration embodies Atari’s unyielding pursuit of arcade perfection. Its genius lies in its layered mechanics—enemies as distinct characters, mushrooms as dynamic terrain, and a scoring system that rewards both skill and risk-taking. Yet, this brilliance is tempered by unforgiving difficulty and the shadow of Centipede, whose simplicity defined a generation. As a historical artifact, Millipede epitomizes the early 1980s arcade ethos: unapologetically hard, visually vibrant, and mechanically dense. Its legacy is one of influence and endurance—a blueprint for future shooters like Smash TV, and a testament to the enduring appeal of precision under pressure. While its home ports faltered, the arcade original remains a masterwork of design, where the garden’s beauty and the insects’ horror collide in a pixelated ballet. For historians and gamers alike, Millipede is not just a relic—it is a reminder that true greatness lies in the tension between refinement and chaos. Final verdict: A flawed masterpiece, but essential for understanding the evolution of the shoot-’em-up genre.