- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

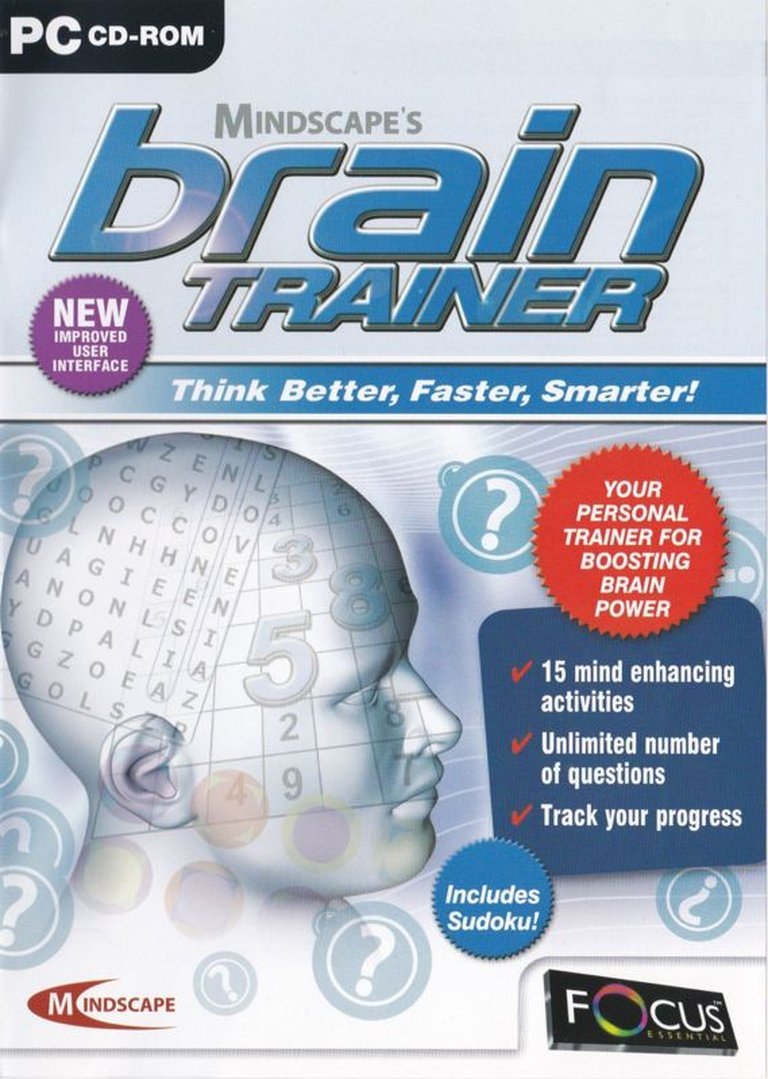

- Publisher: Focus Multimedia Ltd., Mindscape SA

- Developer: Mindscape (UK) Limited, Oak Systems Leisure Software Ltd

- Genre: Puzzle

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Drag-and-drop, Math puzzle, Spatial puzzle, Timed, Word puzzle

- Setting: Educational

- Average Score: 0/100

Description

Mindscape’s Brain Trainer is a puzzle game designed to enhance cognitive skills through daily 10-15 minute workouts featuring timed challenges in five categories: Verbal, Numerical, Spatial, Memory, and Logic. Players solve tasks like anagrams, mental arithmetic, spatial reasoning, memory games, and logic puzzles via mouse interactions, with scores tracked and difficulty increasing as players progress. The game aims to improve academic and everyday life skills through progressively challenging brain exercises.

Mindscape’s Brain Trainer Cracks & Fixes

Mindscape’s Brain Trainer Guides & Walkthroughs

Mindscape’s Brain Trainer: Review

Introduction

In the mid-2000s, the gaming landscape was revolutionized by Nintendo’s Dr. Kawashima’s Brain Training and Big Brain Academy, which popularized the idea of interactive cognitive workouts. Released in 2006, Mindscape’s Brain Trainer emerged as one of the first PC-exclusive entries in this burgeoning genre. Developed by Oak Systems Leisure Software for the publisher Mindscape SA, this title promised to sharpen users’ mental faculties through a regimented daily regimen of 15 timed puzzles. As a self-proclaimed “10-minute mental workout,” it positioned itself as a digital gym for the mind, claiming scientific backing for its ability to enhance academic and real-world performance. Yet, while it rode the wave of the brain-training craze, its legacy is one of a functional but ultimately fleeting experiment—a curious artifact of an era when edutainment briefly dominated mainstream gaming. This review deconstructs Mindscape’s Brain Trainer as both a product of its time and a benchmark for the genre’s PC adaptation, examining its design philosophy, mechanical execution, and cultural impact.

Development History & Context

Mindscape’s Brain Trainer was a strategic product from a studio with a storied but tumultuous history. Founded in 1983 by Roger Buoy, Mindscape had evolved through multiple corporate iterations—from its origins as a U.S.-based publisher of titles like Déjà Vu and Balance of Power to its acquisition by Pearson plc in 1994 and eventual refocusing in France under Jean-Pierre Nordman in 2001. By 2006, the French entity was leveraging its educational publishing lineage to capitalize on the brain-training boom ignited by Nintendo’s DS titles. The game’s development, handled by Oak Systems Leisure Software with oversight from Mindscape (UK) Limited, reflected a pragmatic approach: it targeted a growing demographic of PC users seeking accessible mental exercises, leveraging the platform’s mouse-based input for intuitive puzzle interaction.

Technologically, the game was modestly ambitious. Its requirements—PIII 1GHz CPU, 128MB RAM, and DirectX compatibility—were attainable for mid-2000s PCs, though its reliance on mouse controls (no typing) simplified its design. The gaming context was pivotal: after Nintendo’s success, publishers like Mindscape scrambled to replicate the formula for non-console audiences. Mindscape’s Brain Trainer entered a saturated market of edutainment titles, including 2005’s Brain Boost: Gamma Wave for DS and 2007’s Brain Booster for PC. The developers emphasized “unlimited questions” to ensure longevity, a direct counter to the perceived limitations of console-based puzzles. Yet, despite its focus on scientific credibility (citing “experts” in its promotional materials), the game’s development lacked the neuroscientific rigor of Nintendo’s collaborations, opting instead for broad accessibility over specialized depth.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

As a puzzle collection, Mindscape’s Brain Trainer eschews traditional narrative elements. Instead, its “plot” unfolds through the player’s daily commitment to cognitive improvement. The game frames itself as a personal journey of self-enhancement, where each puzzle is a step toward mental acuity. The recurring theme is transformation: the player begins as a “couch potato” and evolves into a “sharp problem-solver” through disciplined practice. This is reinforced by the practice/daily test dichotomy, with the latter serving as a ritualized checkpoint for progress.

The dialogue is minimal, limited to instructional prompts and score feedback, but the subtext is clear: the player is in a constant battle with their own limitations. The PASS button, which penalizes scores by deducting points, embodies this struggle—it’s a concession to frustration but a reminder that true growth requires perseverance. Thematically, the game champions quantifiable self-improvement, mirroring 2000s-era productivity culture. However, its lack of narrative cohesion or characters renders it impersonal. Unlike Dr. Kawashima’s Brain Training, which integrated a framing device with the titular neuroscientist, Mindscape’s Brain Trainer feels sterile. Its “expert” endorsements feel like afterthoughts, and the absence of a narrative arc reduces the experience to a series of disconnected drills. This thematic flattening underscores the game’s primary weakness: while it claims to enhance “everyday life,” it never contextualizes how these abstract puzzles translate to real-world skills.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The core gameplay loop revolves around daily 10-minute sessions, comprising one randomly selected puzzle from each of five categories: Verbal, Numerical, Spatial, Memory, and Logic. This structure ensures variety while enforcing consistency. Puzzles escalate in difficulty based on performance, creating a subtle progression system. Each category offers three distinct activities, totaling 15 exercises:

- Verbal: Anagrams (decoding US States or similar words), Spelling Tests (identifying correctly spelled words from trios), and Word Searches (locating 10 words in a 10×10 grid).

- Numerical: Mental Arithmetic (multiple-choice sums), Number Crunch (placing operators like +/− to balance equations), and Number Sequence (identifying the missing number in a pattern).

- Spatial: Four Color (filling a pattern with four colors without adjacent clashes), Colour Matching (finding identical geometric designs), and Fold the Cube (visualizing 3D cubes from 2D nets).

- Memory: Follow the Leader (Simon Says with symbols), Matching Pairs (memorizing symbols and reconstructing pairs post-hiding), and Memory Grid (rebuilding a tile grid after a brief preview).

- Logic: Color Tiles (arranging tiles to match border colors), Connexagon (rotating hexagonal wheels to unify colors), and Sudoku (a simplified 1-4 grid version).

The mouse-driven interface is intuitive—dragging and clicking dominate interactions—but this simplicity reveals flaws. Timed challenges create artificial pressure, and the PASS button, while merciful, undermines the difficulty curve. Scoring is punitive: errors and skipped questions lower rankings, and progress tracking relies on rudimentary line graphs comparing daily performance. The daily test structure prevents player agency, forcing acceptance of random puzzles. Additionally, some activities suffer from poor design—like the Sudoku variant’s arbitrary difficulty scaling or the Four Color puzzle’s fiddly controls. The game’s claim of “infinite questions” is technically true but misleading; puzzles repeat with slight variations, limiting replayability.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Mindscape’s Brain Trainer exists in a self-contained, sterile world—a digital “gym” devoid of narrative settings. Its art direction is functional, prioritizing clarity over flair. Puzzles use minimalist geometric shapes, clean fonts, and high-contrast colors (e.g., primary hues for the Four Color challenge). This visual simplicity aids readability but induces monotony. Screenshots reveal a drab, gray interface with static backgrounds, lacking the whimsical charm of contemporaries like Big Brain Academy. The only “atmosphere” is one of clinical detachment, reinforcing the game’s utilitarian ethos.

Sound design is equally austere. A single, repetitive piano theme plays in loops, punctuated by sharp clicks for mouse inputs and flat voice-overs for instructions. The absence of dynamic audio or adaptive feedback makes sessions feel impersonal. While this minimalist approach aligns with the game’s no-frills premise, it fails to engage players emotionally. The visual and audio presentation, efficient as it is, underscores the game’s core limitation: it reduces cognition to a mechanical exercise, stripping away the joy of discovery that defines great puzzle games.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Mindscape’s Brain Trainer garnered lukewarm reception. Critics noted its similarity to Nintendo’s DS titles but criticized its lack of personality and depth. itreviews.com (2006) remarked that it was “like the Nintendo game, but not,” implying imitation without innovation. Commercial data is sparse, but the game’s budget price point (£9.99 CD/download) suggests a niche audience. No critic reviews appear on Metacritic or IGN, reflecting its obscurity beyond puzzle enthusiasts.

Over time, its reputation has soured. Modern retrospectives dismiss it as a derivative cash-in, overshadowed by more polished brain-training games like Smarter Brain Trainer (2009). Its legacy lies in its timing: as one of the first PC adaptations of the genre, it highlighted the limitations of porting touch-screen experiences to mouse-driven interfaces. The game’s emphasis on “unlimited questions” and daily routines influenced later titles, but its mechanical flaws—especially the punitive scoring and random puzzle selection—set precedents for poor design in edutainment. The defunct Mindscape (liquidated in 2011) further cemented its status as a historical footnote, a relic of an era when brain-training was a fad rather than a lasting genre.

Conclusion

Mindscape’s Brain Trainer is a fascinating if flawed artifact of 2006’s edutainment boom. It delivers on its promise of accessible cognitive exercises with a robust suite of 15 puzzles, but its sterile presentation, punitive mechanics, and lack of narrative cohesion prevent it from transcending its genre’s limitations. As a PC pioneer in brain training, it demonstrated the challenges of adapting console concepts to different inputs—mouse controls simplified interactions but stripped away the tactile satisfaction of the DS. Its legacy is one of missed potential: a competent but uninspired product that capitalized on a trend without innovating. For historians, it serves as a case study in the commodification of “brain fitness,” while for players, it remains a curiosity—a time capsule of a moment when games were marketed as digital medicine. Ultimately, Mindscape’s Brain Trainer earns a middling verdict: it succeeded as a functional tool for casual mental workouts but failed to leave a lasting mark on gaming history. In the crowded field of puzzle games, it’s a forgotten experiment—one that reminds us that not every mental workout needs to be fun to be remembered.