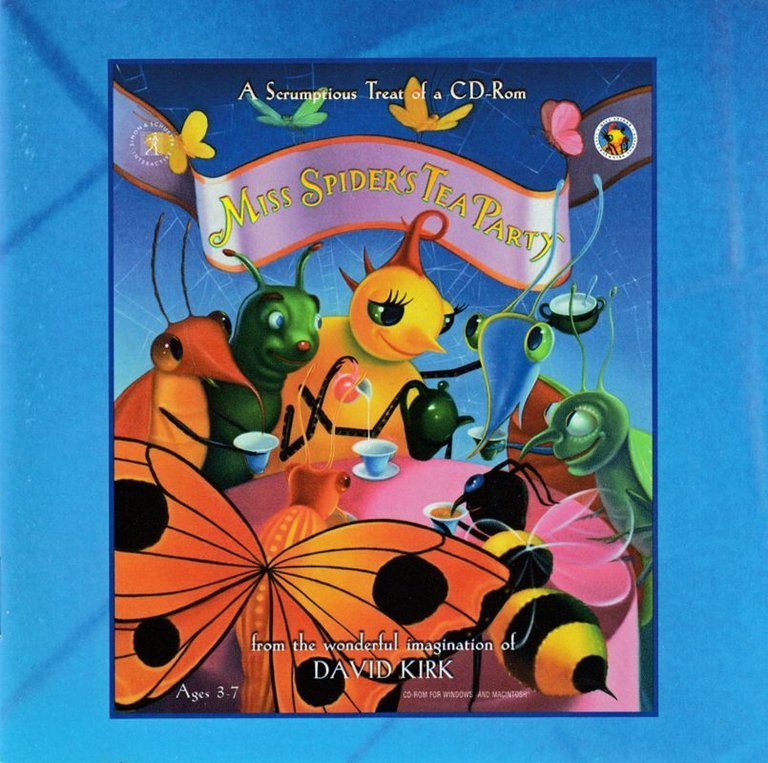

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Macintosh, PlayStation, Windows

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Interactive

- Developer: Hypnotix, Inc.

- Genre: Adventure, Educational, Mini-game, Party

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: logic, Math, Mini-games, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Children’s book, Insect world

- Average Score: 47/100

Description

Miss Spider’s Tea Party is an educational adventure game designed for children aged 3 to 7, set in the vibrant, whimsical world created by author David Kirk. Players assist Miss Spider’s insect friends—such as beetles, crickets, bees, and butterflies—in overcoming a series of playful challenges, including river crossings, musical matching, flower pollination, and butterfly hide-and-seek, through a collection of eight mini-games. Each puzzle helps the characters reach Miss Spider’s tea party, with success unlocking a personalized printable invitation. The game features charming 3D visuals and animations inspired by the original children’s book, offering adjustable difficulty levels and age-appropriate skill-building in logic, memory, and basic math.

Gameplay Videos

Miss Spider’s Tea Party Free Download

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

gamefaqs.gamespot.com : Miss Spider’s Tea Party is a very short game that can be cleared in just a few minutes, but its a surprisingly decent game for a 90s edutainment title.

mobygames.com (54/100): Miss Spider’s Tea Party invites children 3 to 7 years old to enter children’s book author David Kirk’s world of color and wonder.

honestgamers.com : Educational games that teach youngsters a few bits of basic education, yet providing some wholesome fun while doing it.

backloggd.com (40/100): When Miss Spider states at the end that everyone is invited it sent a chill down my spine, as now there was a chance higher than 0 that if I attended to such events, I could potentially bump into stuttering game critic Joseph Anderson.

Miss Spider’s Tea Party: Review

Introduction

In the golden age of edutainment, when publishers sought to blend nascent 3D technology with the timeless appeal of children’s literature, one often-overlooked title crawled quietly onto the digital landscape: Miss Spider’s Tea Party. Developed by Hypnotix, Inc. and published by Simon & Schuster Interactive in 1999, this seemingly innocuous educational adventure game carved a modest but curious niche in the pantheon of children’s video games. Based on David Kirk’s beloved children’s book series—the foundation of the Sunny Patch franchise—the game attempts to translate Kirk’s bulbous, technicolor insect world into an interactive experience for children aged 3 to 7. Its premise is simple: Miss Spider is hosting a tea party, but her insect friends are beset by logistical, physical, or emotional obstacles. The player, child or adult, must help them overcome these hurdles through eight mini-games ranging from river crossings to memory matching.

But beneath its candy-coated exterior lies a tangled web of design inconsistencies, technological limitations, thematic dissonance, and a fascinating case study in the late-1990s edutainment boom. While contemporaneous titles like Reader Rabbit or Dora the Explorer evolved into pedagogical institutions, Miss Spider’s Tea Party became a relic of a transitional era: too ambitious for its intended audience, too simplistic for older children, and too technically uneven to leave a lasting legacy. Yet, as a game historian, to dismiss it as merely another casualty of the edutainment jukebox would be to overlook the multilayered contradictions that make Tea Party a compelling artifact of its time.

This review aims to disentangle those layers. Drawing from primary sources across MobyGames, GameFAQs, retro archives, user testimonials, and studio credits, we will explore not only what the game is, but why it exists, how it was received, and why its legacy remains paradoxically both negligible and noteworthy. My thesis is this: Miss Spider’s Tea Party is an ambitious, occasionally brilliant, but fundamentally compromised educational game that reflects the cultural and technological tensions of 1999—its flaws are not just design failures, but symptoms of a genre struggling to define itself in the face of rising commercial expectations, maturing interactive storytelling, and the increasing sophistication of childhood development discourse. It is, in short, a failed masterpiece—or, more accurately, a masterpiece of failure.

Development History & Context

The Studio: Hypnotix, Inc. – From Adult Humor to Insect Underwear

Founded in the early 1990s, Hypnotix, Inc. was an American developer with a remarkably eclectic and tonally inconsistent portfolio. While Miss Spider’s Tea Party featured pastel insects and kindergarten-level logic puzzles, the same development team contributed to projects like Panty Raider: From Here to Immaturity (1999), a risqué first-person romp involving scantily clad women, panty collection, and absurd dialogue—a game that makes Miss Spider’s city limits feel like another planet. Between these two extremes sat Daria’s Inferno (1999), a cynical, satirical adventure game, and Sabrina, the Teenage Witch: Brat Attack, a licensed teen-comedy cash-in.

This duality underscores the operator model common to mid-tier developers of the era: studios often swapped personnel and codebases across vastly different genres, leading to a kind of creative dissonance. In Hypnotix’s case, key figures like Jeffrey M. Siegel (credited on 72 other games), Michael Taramykin (executive producer), and Jason M. Shenkman (art director) moved fluidly between adult-oriented comedy, licensed children’s games, and educational software. The same animators (John Amos) who designed Miss Spider’s gentle, 3D-animated crawl were likely at work on the risque gags of Panty Raider.

This context is vital: Miss Spider’s Tea Party was not the product of a dedicated children’s game studio, but rather one arm of a corporate machine designed to exploit multiple audience niches. The game’s tone, art, and mechanics were likely sculpted not by child development specialists, but by a team balancing commercial mandates, licensor demands, and internal resource constraints.

Publisher Legacy: Simon & Schuster Interactive – The Bookshelf Goes Digital

Simon & Schuster Interactive (SSI) was the digital offshoot of the venerable publishing house, established in the late 1980s to adapt its intellectual property for CD-ROMs and early digital distribution. SSI published a mix of literacy games, phonics toolkits, and full-fledged edutainment titles under a “money-back learning guarantee.” Their catalog included classics like Where in Time is Carmen Sandiego?, Escape from Brisfer, ReBoot: The Guardian Code, and licensed fare like Richard Scarry’s Busytown.

SSI’s strategy was clear: leverage trusted literary brands into interactive formats for the burgeoning home computer market. In 1994, author David Kirk published Miss Spider’s Tea Party with Scholastic Press, establishing the character and her Sunny Patch insect friends as a commercial success. By 1999, SSI saw potential in adapting Kirk’s visual world—“a world of color and wonder,” as the official description puts it—into a game that would appeal to parents seeking safe, educational alternatives to violent or commercialized games.

Thus, Miss Spider’s Tea Party was not an original creation, but a licensed adaptation, a crucial distinction. Unlike games developed in-house with true creative freedom, licensed titles must adhere to brand guidelines and marketing strategies. The game’s structure—eight mini-games solving insect problems—was likely mandated to emulate the episodic, problem-solving format of the books, ensuring brand fidelity. The decision to include a printed invitation as a reward was a clear nod to the sentimental value of physical objects, a relic of pre-internet material culture.

Technological Constraints & the 1999 PC Landscape

Released on Windows and Macintosh in 1999, then on PlayStation in 2000, the game straddled the transition from CD-ROM-based edutainment to console hybrid experiences. On PC, it ran from a CD-ROM and supported mouse input—a critical limitation, as noted in user reviews: young children, especially ages 3–5, struggle with fine motor control and mouse precision.

Hypnotix employed 3D pre-rendered environments and character models, a hallmark of late-90s edutainment (e.g., The Learning Company’s titles). The game featured 3D animation, cinematic cutscenes with full voiceacting, and dynamic lighting. However, these elements were rushed, muddy, and inconsistently rendered. As one user lamented, “The graphics were muddy, on my PC at least, making some of the puzzles very unclear (e.g. black ant tunnels through brown dirt were hard to see).”

This was symptomatic of broader technological issues:

– Budget limitations: 41 credited people (39 developers, 2 thanks) for a 1999 multiplatform release was small, even for edutainment. Compare this to Adventures in Wonderland (1996), which had over 100.

– Engine reuse: Hypnotix likely used a generic in-house engine later repurposed for games like Daria’s Inferno, adapting lighting and camera logic poorly for a children’s game.

– Audio fidelity: The GameFAQs review observes, “All of the music sounds like you gain staged and recorded a live band far too low… incredibly poor fidelity.” This suggests budget studio recordings or degraded MIDI files, possibly compressed for CD space.

– Console adaptation: The PlayStation version, released in late 2000, used dual analog sticks—a transformative input method for young players. As Jane VR noted, “PlayStation controls might be more manageable.” Yet SSI may have underutilized this advantage, not redesigning controls for analog precision.

The 1999 Edutainment Boom: A Bubble About to Pop

1999 was a peak year for edutainment before the dot-com crash and the rise of the internet disrupted the CD-ROM business model. Publishers scrambled to digitize everything: from phonics drills to full narrative adventures. The NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children) was just beginning to publish early guidelines on screen time and learning design, emphasizing engagement, feedback, and developmental appropriateness—concepts often ignored in practice.

Tea Party entered this environment as a retrograde “game-based” edutainment title, as classified by the Game Classification Project. Unlike the “embedded learning” of Sesame Street games, which wove education into narrative, Tea Party used explicit mini-games separated by cutscenes—a design philosophy that presaged the “experience as progress” model later popularized by mobile games.

Yet it also arrived at the tipping point of pedagogical skepticism: critics like Jane S. Richardson and Steven J. CZAJA questioned whether digital play actually enhanced early learning, a debate intensified by the empirical vagueness of developer claims. Hypnotix’s own battle with control design and difficulty scaling—criticized as “not tested on kids”—was part of a systemic failure across the genre.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot: The Meta-Narrative of Inclusion and Exclusion

The game’s plot, as described in the introduction, is deceptively simple: “Miss Spider’s friends want to attend her party, but they each have a problem that needs to be resolved.” This anthropomorphic problem-of-the-day structure directly mirrors the format of children’s picture books and animated shows, where episodic challenges reinforce social and emotional skills.

But beneath the surface, the narrative reveals a curious anxiety about belonging and exclusion:

– The Beetles cannot cross the river (a Frogger-style game).

– The Crickets lack a band (a sound-matching puzzle).

– The Bees must pollinate flowers (a memory game).

– The Butterflies are in hiding (a Where’s Waldo? search).

– The Fireflies need to find their match (a memory match).

– Grampy Spider must organize his albums (a caption-matching task).

– The Caterpillar and Moth must race down a hill (a fast-paced dodge game).

– Mr. Ant must find his way through a maze (a first-person navigation challenge).

Each mini-game, therefore, becomes a metaphor for a social or psychological barrier:

– The “river” as a metaphor for fear, isolation, or insecurity.

– The “polishing” of flowers by bees as a metaphor for adult responsibilities (“I have to pollinate!”).

– The “search for the match” as a metaphor for identity and belonging.

The narrative climax—the tea party—is not a grand celebration, but a quiet, non-interactive cutscene. All insects are shown sitting, eating, smiling. There is no performance, no entry, no fanfare. Miss Spider thanks the player with a printed invitation, a tangible token of inclusion. This is deeply symbolic: the game, like the party, is about being seen, being allowed in.

Yet, the game mechanics often work against this emotional core. Insect problems are often trivialized:

– “The Crickets want to form a band” — a potentially rich exploration of music, collaboration, and artistic expression — becomes a rote memory game.

– “The Bees have to pollinate” — a profound ecological task — is reduced to “here’s a picture, match the flower.”

– “The Butterflies are hiding” — a poetic metaphor for anxiety — becomes a eye-straining, DRM-tier search puzzle.

This disconnect between narrative weight and mechanical triviality is the game’s central thematic flaw. It wants to say, “Everyone belongs,” but the gameplay says, “Only if you can match colors fast.”

Characters: Anthropomorphic Flatness

The characters are stock types, drawn directly from children’s media tropes:

– Miss Spider: The nurturing matriarch (voiced in the style of a kindergarten teacher—per GameFAQs), whose voice carries vocal fry and warmth.

– The Beetles: A rock band, but unnamed, faceless, and inconsistent (“Why can’t beetles fly?” asks cdbavg400).

– The Crickets: The musically challenged, represented by mismatched instruments.

– The Fireflies: The identity-seekers, “looking for their match.”

– Grampy Spider: The forgetful elder, struggling with organization.

– The Caterpillar and Moth: Ambiguously in a relationship, racing separately—yet their paths are identical.

– Mr. Ant: The neurotic drudge, afraid of being late.

No dialogue is attributed to any of them beyond the opening cutscene. They are silent spectators with light-up subtitles. This deprives the game of character development or interaction, reducing them to puzzle triggers.

Miss Spider’s voice-acting is notably full voiced throughout the PC and PlayStation versions, a rare feature in children’s games of the era. She offers praise (“You’re doing purrr-factly!” — despite not being a cat), comfort (“Don’t worry, little bug!”), and urgency (“We’re running out of tea!”). Her performance, as noted by Rin-Coconut, “sounds like a kindergarten teacher super nice to everyone,” creating emotional anchoring. Yet the other insects lack this consistency—some voices are clear, others drowned in noise.

Thematic Undercurrents: Anxiety, Speed, and Literalism

Three themes emerge from the narrative and gameplay:

1. Anxiety of Delay: Many insects fear being “late” or “too busy” (Mr. Ant: “Miss Spider will be so disappointed if I am late!”). This reflects the industrialization of childhood, where even play is presented as a checklist to be completed.

2. Speed as Reward: The hardest mini-game—Caterpillar/Moth racetrack—favors speed over learning. As Rin-Coconut notes, it was “a bit of a challenge to clear, and that’s coming from someone who plays Touhou.” For a 3-year-old, this is developmentally inappropriate.

3. Literalism in Literacy: The game reduces abstract concepts (band membership, pollination, friendship) to mechanical micro-tasks, flattening them into puzzles. This is anti-educational pedagogy, prioritizing completion over comprehension.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Mini-Game Collectathon

The game follows a nonlinear collectathon structure:

– Eight mini-games, no required order.

– Each playable on Easy, Medium, Hard (hummingbird, dragonfly, firefly).

– Parental meta-reward: a printable invitation upon completion.

– Short runtime: 20–45 minutes, “absurdly short” (GameFAQs).

This design embodies the CD-ROM “activity center” model—a format that offered variety but little depth. Unlike The Learning Company’s titles, which built skill scaffolding over 20+ levels, Tea Party treats each mini-game as modular and disposable.

Mini-Game Breakdown

1. Beetles River Cross Game (Action)

- Mechanic: Flicker-based hopping on platforms (leaves, tadpoles, rocks).

- Innovation: Simplified Frogger without enemies.

- Flaw: Precise timing ignored by mouse control. As Jane VR noted, “Way too difficult for a small child on PC.”

- Psychology: Tests hand-eye coordination and peripheral awareness.

2. Moth/Caterpillar Obstacle Course (Action)

- Mechanic: High-speed downhill dodge game with narrow lanes.

- Innovation: Fastest, most intense action—described as “racing down at the speed of light.”

- Flaw: Impossible for young children; relies on course memorization.

- Psychology: Tests reaction time and visual prediction—skills that develop around age 7.

3. Cricket Band Game (Matching)

- Mechanic: Match instrument type (trombone, clarinet) to cricketer’s sound.

- Innovation: Early musical education tool.

- Flaw: Instruments are abstract and unknown to young kids (GameFAQs).

- Psychology: Tests auditory memory and categorization—but with poor scaffolding.

4. Bee Flower Matching Game (Memory)

- Mechanic: Remember a flower, then select from 3 slower presentations.

- Innovation: Focus on visual detail (“number of leaves, thorns, stem shape”).

- Flaw: One-time exposure, no repetition—memory burden too high.

- Psychology: Tests short-term visual memory.

5. Hiding Butterfly Game (Search & Seek)

- Mechanic: Find color-coded butterflies camouflaged in flora.

- Innovation: None. Standard “I-Spy” template.

- Flaw: Pixel-level precision required, causing eye strain.

- Psychology: Tests visual discrimination.

6. Firefly Concentration Game (Memory)

- Mechanic: Classic 4×4 card flip with fly colors.

- Innovation: Thematically appropriate.

- Flaw: All fireflies look identical (Rin-Coconut: “I swear they’re identical!”).

- Psychology: Tests working memory—but with false negatives.

7. Grampy Spider’s Picture Perfect (Drag & Match)

- Mechanic: Drag caption (“Two Butterflies”) to correct image.

- Innovation: Word-to-image linkage.

- Flaw: Overly ambitious vocabulary for age 3–7 (e.g., “crimson,” “fuchsia”).

- Psychology: Tests comprehension and visual matching.

8. Mr. Ant’s Maze (Navigation)

- Mechanic: First-person pathfinding through “underground” tunnels.

- Innovation: Rare 3D navigation in a children’s game.

- Flaw: Z-fighting, poor camera, voice clip of anxiety.

- Psychology: Tests spatial reasoning.

Progression, Difficulty, and Player Freedom

The difficulty inconsistency is the game’s cardinal sin:

– “Easy” puzzles are too simple (“click the red butterfly”).

– “Hard” puzzles are incredibly difficult (course memorization, near-invisible matches).

– No dynamic scaling—hard mode on Butterfly game is nearly unplayable due to low-contrast art.

Player freedom is high (choose any order), but motivation is low. No narrative consequence for skipping a game; no meta-progression. The only reward is the ephemeral cutscene.

UI & Accessibility:

– No save system—you must complete all eight in one session.

– No toolipps or advice—children are left to guess controls.

– Static difficulty—no adaptive learning.

– No feedback beyond “Good job!”—minimal positive reinforcement.

The decision to use mouse instead of keyboard or simple directionals on PC is a critical design failure. As cdbavg400 notes, it “doesn’t seem like they actually tested this game on any kids.”

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Direction: The Conflict of Kitsch

The game attempts to emulate David Kirk’s childlike, blobby art style: rounded insects, studio-lit environments, 3D-rendered with soft shadows. The result is a charming but technically flawed aesthetic:

– 3D models of insects are cute and expressive, with big eyes and cartoon proportions.

– Environments are colorful, with muddy, compressed textures (brown dirt, black tunnels).

– Cutscenes: Short, pre-rendered CGI, often blurry—likely due to time constraints.

Artistically, it sits between Pixar’s A Bug’s Life (1998) and cement-style CD-ROM production. The firefly designs are indistinguishable, a major flaw for a memory game.

Sound Design: Licensed Pastels, Degraded Fidelity

The music is a mix of:

– Lo-fi MIDI jazz (as Rin-Coconut observes), with poor jitter control.

– Cheerful, repetitive jingles for mini-games.

– No dynamic scoring—music plays linearly.

The voice acting is full-cast and unexpected, a rarity. Miss Spider is warm and encouraging. The Crickets have “cool jazz cat” energy. Mr. Ant is nasally and anxious. Yet background noise, pops, and silence gaps mar the experience (“I don’t think that was intentional,” Rin-Coconut).

The sound effects are praised: “clicks and beeps are outstanding” (HonestGamers). This suggests audio was a minor priority, a cost-cutting area.

The rating of “not as bad as some” in cutesy audio is telling: it clears the low bar for the genre.

Reception & Legacy

Initial Reception: The Harsh Reality of Playtesting

Upon release, Miss Spider’s Tea Party received scant critical attention. No reviews on Metacritic. No major awards. On MobyGames, it has a 2.7/5 average from 2 ratings, one review:

Jane VR (2004): “Not a good game… difficulty level all over the place… arcade sections way too difficult… puzzle sections were very easy on easy and quite hard on hard… doesn’t seem like they actually tested this game on any kids.”

The HonestGamers review (3/5) praises audio and graphics but calls the game “short as an M&M.” cdbavg400 notes the irony of an anti-recycled concept: “Imagine, a game that’s different from Frogger… but it’s not.”

Fan sentiment is divided:

– Nostalgic adults: “This was the first game I ever played” (Elephant_Parade).

– Modern historians: “A chill down my spine” over Joseph Anderson references (maradona).

– Critics: “Only two games are fun,” one user said—both action-oriented.

Commercial Fate: A Ghost Game

No sales figures exist. The game was not a commercial hit, priced at retail for ~$50 (inflation-adjusted). It was not heavily marketed, no TV ads. The PlayStation version sold for $0.99 used—indicating low demand.

By 2006, a sequel—Miss Spider’s Scavenger Hunt—was released, suggesting ongoing IP interest. Yet the franchise failed to scale.

Legacy: A Mirror to a Dying Genre

Tea Party stands as a microcosm of the edutainment bubble:

– It shows the limits of mini-game collectathons as educational vehicles.

– Its control issues highlight the lack of accessibility standards in children’s games.

– Its narrative/mechanic dissonance anticipates modern debates about “educational ghosts” (Squire, 1996).

– Its abandoned console port—PlayStation with analog sticks—was potentially revolutionary, but underdeveloped.

It influenced no major franchises. It inspired few sequels. But it resonates in the history of play-based learning, a cautionary tale.

Modern games that inherit its spirit—but improve upon it—include:

– Sesame Street: Alphabet Kitchen (2015) – contextual learning.

– Pocoyo: Colors and Shapes – adaptive difficulty.

– Pre-K Phonics – voice feedback and progress tracking.

Tea Party, by contrast, offers neither.

Conclusion

Miss Spider’s Tea Party is not a good game by modern standards. It is too short, too easy in parts, too hard in others, too inconsistent, too poorly tested. Its graphics are muddy, its mechanics shallow, its educational value debatable. Its mouse controls are unforgivable in the context of its audience.

And yet.

Within its eight mini-games, a spark of innovation flickers. The Moth/Caterpillar dodge game is genuinely thrilling—a hidden hardcore gem. The Cricket Band game is ambitious in its musical pedagogy. The world design is charming, the voice acting is conspicuous, the narrative premise is emotionally potent. It features 3D animation, full voiceacting, a nonlinear structure, and difficulty options—features absent from 90% of its contemporaries.

It is a game caught between worlds: not just child and adult, but between the dying CD-ROM era and the rising console market, between licensed loyalty and creative freedom, between educational theater and genuine learning.

Like a fragile, translucent butterfly, Miss Spider’s Tea Party flutters briefly on the edge of history, its wings slightly too weak to fly, too beautiful to dismiss. It is not remembered, but it is preserved—in MobyGames archives, in a grandmother’s attic PC, in the GameFAQs review that calls it “the downhill dodge ’em game and Frogger clone pretending to be an edutainment game.”

That sentence, more than any other, captures its essence. And for the historian, the analyst, the lover of forgotten games, that is enough.

Final Verdict:

Miss Spider’s Tea Party is a failed genius. It is not a classic. It is not even a “so bad it’s good” curiosity. But it is a symptom, a symbol, and a silent witness to a time when the interactive form was still learning how to teach without condescending, to play without selling, to include without excluding.

In the future, when scholars examine the rise and fall of edutainment, they may not call Tea Party a masterpiece.

But they will call it necessary.

Rating (Historical Significance):

⭐⭐⭐½

(3.5/5 – Flawed, but foundational in its missteps)

Rating (Play Value):

⭐⭐

(2/5 – Only for nostalgia or study; avoid for children)

Place in History:

A necessary anomaly in the evolution of children’s interactive media.