- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: WildTangent, Inc.

- Developer: Conductor, LLC

- Genre: Simulation

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Dating simulation

- Setting: Contemporary, North America

- Average Score: 60/100

Description

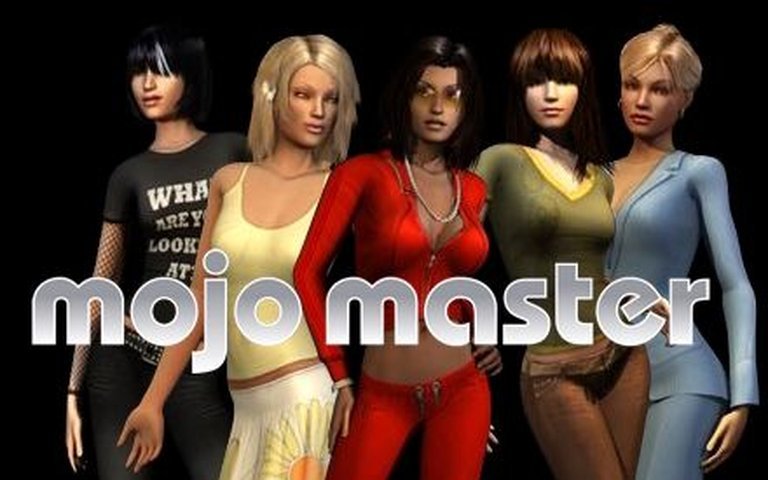

Mojo Master is a 2005 dating simulation game developed by Stuart Moulder in collaboration with Unilever to promote AXE Unlimited body spray. Players embark on a mission to seduce and collect phone numbers from 100 virtual women across seven American cities, each categorized by elemental traits like Light, Fire, Earth, Ice, and Shadow. The game features unique moves and accessories tailored to each character’s element, with Tiffany Fallon, the 2005 Playboy Playmate of the Year, as one of the featured characters.

Mojo Master Reviews & Reception

gamefaqs.gamespot.com (60/100): A nice way to kill time when you have nothing to do. It’s worth a play once, but since the Girls seem to be the same every time, there isn’t much replay value.

Mojo Master Cheats & Codes

Mojo (NTSC-U)

Enter the following hex code pairs via the CodeBreaker (or GameShark) system while playing Mojo on a PS2 console or an emulator supporting NTSC-U firmware.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| B4336FA9 4DFEFB79 | Enable Code (Must Be On) |

| 918F6152 28E02786 | Enable Code (Must Be On) |

| B659C6AB 8263A974 | Enable Code (Must Be On) |

| 2F36CCC8 FB18C0BE | Enable Code (Must Be On) |

| DE5165AC 32B36DEA | Always Low Time |

| 4B02AC29 6A835469 | Quickly Get All Red Blocks |

| 6D760026 D0A26FFF | Quickly Get All Green Blocks |

| 697AD5A1 519938B5 | Quickly Get All Blue Blocks |

| D473166B 80B34323 | Quickly Get All Yellow Blocks |

| 530BF95E 3E3A5BA4 | Quickly Get All Mojo Blocks |

| BF7318A9 9496759D | Infinite Health |

| FEE1850B 97E45CAC | Infinite Health |

| 00A31484 1F1C6C43 | Infinite Turbo |

| 0044A433 0F741D93 | Infinite Turbo |

Mojo Master: A Deep Dive into the Controversial Advergame of 2005

Introduction

In the mid-2000s, as the digital landscape exploded with experimental advergames and casual simulations, Mojo Master emerged as a brazen, unapologetic product of its time—a dating simulator co-developed by Stuart Moulder and Unilever to promote AXE Unlimited body spray. Released on June 20, 2005, this first-person title tasked players with seducing 100 virtual women across seven American cities, each categorized into elemental archetypes (Light, Fire, Earth, Ice, Shadow). While dismissed by critics as a shallow marketing ploy, Mojo Master occupies a fascinating niche in gaming history—a relic of a pre-social media era where brands dared to gamify male fantasies. This review deconstructs its origins, mechanics, and legacy to argue that beneath its commercial veneer lies a provocative, if flawed, artifact of early 2000s digital culture.

Development History & Context

Mojo Master was conceived by Stuart Moulder, a veteran game producer known for his work at LucasArts, in partnership with Unilever’s AXE brand. As the 2000s dawned, body-spray marketing leaned heavily into exaggerated “pheromone-driven” narratives, positioning AXE as the ultimate tool for attracting women. Moulder’s studio, Conductor, LLC, was tasked with translating this concept into an interactive experience. Technologically, the game leveraged basic 3D environments typical of early 2000s casual titles, with minimal hardware demands to ensure broad accessibility on Windows XP systems. The gaming landscape of 2005 was dominated by the rise of downloadable casual games and MMOs, while advergames like Mojo Master exploited the burgeoning market for browser-based and free-to-play content. Unilever’s investment reflected a broader trend where corporations treated games not just as ads, but as narrative extensions of their brands—a strategy that felt both innovative and audaciously reductive.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The plot is a thinly veiled power fantasy: players assume the role of a “Mojo Hunter” seeking to conquer 100 women and earn the title of “Mojo Master.” Each woman belongs to one of five elemental categories, dictating compatibility with the player’s “moves.” The narrative is delivered through minimal dialogue and text prompts, reinforcing the game’s transactional nature. Characters lack depth beyond archetypes—Tiffany Fallon, the 2005 Playboy Playmate, appears as a celebrity cameo but contributes little to the story. Thematically, Mojo Master reduces human connection to a mechanical system of “elemental matchups” and “accessory-based seduction.” Its themes are overtly misogynistic, framing attraction as a puzzle to be solved with the right spray or outfit. This reductionism is both the game’s greatest flaw and its most telling artifact—a product of Axe’s hyper-masculine marketing ethos, where women are targets, not characters.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core gameplay revolves around three loops:

1. Exploration: Players navigate seven stylized cities (e.g., Las Vegas, New York), each featuring unique venues (clubs, beaches, gyms).

2. Seduction: Interaction involves selecting “moves” (compliments, dance moves, gifts) tailored to a woman’s elemental type. Success hinges on elemental matchups—e.g., “Fire” moves fail against “Ice” women but succeed against “Earth.”

3. Progression: Players earn “Mojo Points” to unlock new cities, apparel (e.g., AXE-branded outfits), and moves.

The UI is utilitarian, with inventory screens and city hubs resembling a budget RPG. Combat is absent; instead, “conflict” manifests as failed seduction attempts. The elemental system adds strategic depth but feels arbitrary, and the grind of approaching 100 identical NPCs grows tedious. Flaws include repetitive dialogue, a lack of meaningful player choices, and an absence of consequences—each interaction resets to zero, reinforcing the game’s disposable nature. Yet in its simplicity, Mojo Master mirrored the casual gaming boom’s emphasis on quick, bite-sized engagement.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Mojo Master’s world is a hyper-stylized, exaggerated vision of American urbanity. Cities are caricatures: Miami’s neon-lit beaches pulse with tropical energy, while New York’s subway stations hum with gritty authenticity. The art direction leans into cartoonish realism, with brightly colored environments and character models that prioritize accessibility over detail. Women are rendered in a uniform, polished style, their elemental distinctions signaled only by palette swaps (e.g., “Ice” characters wear silver/blue, “Fire” in red/orange). Sound design is sparse, relying on generic club beats and canned voice lines for reactions. The atmosphere is intentionally vapid—a kaleidoscope of hedonism where every location feels like a stage for the player’s conquest. This aesthetic, while technically unremarkable, perfectly captures the product’s aspirational, superficial appeal.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Mojo Master received no critical reviews, a void underscored by MobyGames’ empty reviews section. Commercially, it faded into obscurity, remembered only as a niche curiosity in advergame history. Yet its legacy is more nuanced. It predates the “dating sim” boom of the 2010s (e.g., Hatoful Boyfriend) and highlights brands’ early experimentation with interactive media. Influenced by titles like Mojo! (2003), Mojo Master expanded the “pick-up artist” trope into a game format, albeit with less finesse. Its elemental system, while rudimentary, prefigured the “type-matching” mechanics seen in modern mobile RPGs. Today, it’s studied as a case study in problematic game design—a cautionary tale about reducing human connection to a spreadsheet. Conversely, its unapologetic commercialism has earned it a place in discussions of gaming’s relationship with advertising, alongside titles like Pepsi Invaders.

Conclusion

Mojo Master is less a game and more a time capsule—a product of 2005’s casual gaming boom and Axe’s unapologetically regressive marketing. Its elemental seduction system and city-hopping grind offer fleeting amusement, but its lack of narrative depth and mechanical repetition render it a historical footnote rather than a classic. Yet in its audacity, Mojo Master reveals the tensions of an era where brands and creators collided in the digital space. It is, ultimately, a flawed artifact: technologically primitive, themically questionable, but undeniably emblematic of a moment when games dared to be billboards. For historians and genre enthusiasts, it serves as a stark reminder that not all digital preservation is about preserving greatness—sometimes, it’s about preserving the uncomfortable, the commercial, and the profoundly weird. Final Verdict: A historically significant but artistically hollow entry in the annals of advergames.