- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

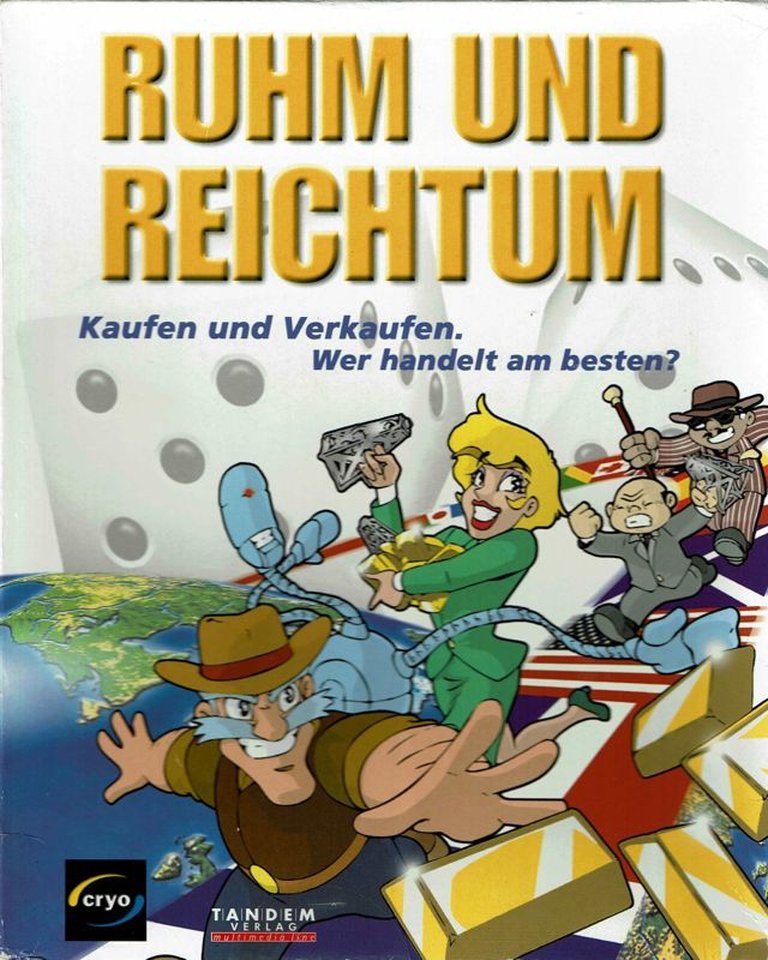

- Publisher: 1C Company, Cryo Interactive Entertainment, Tandem Verlag GmbH

- Developer: Ravensburger Interactive Media GmbH

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Board game, Business simulation, Game show, Managerial, quiz, trivia

- Average Score: 54/100

Description

Money Mad is a 2000 strategy board game adaptation for Windows where players compete to become international moguls. Unlike traditional property games, its scope is global; players roll dice to travel the world, purchase industrial resources like factories and distribution centers, and make corporate decisions to build a financial empire. The ultimate goal is to force all opponents into bankruptcy, and it supports both single-player against AI opponents and competitive hot-seat multiplayer for up to six people.

Money Mad Free Download

PC

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (54/100): Mad Money is a computer adaption of the board game of the same name.

spong.com : Money Mad is an awfully challenging title, and should be taken into purchasing consideration for the financially competitive population.

Money Mad: Review

Introduction

In the annals of video game history, nestled between the blockbuster 3D adventures and the burgeoning online multiplayer revolution of the early 2000s, lies a curious artifact: Money Mad. Developed by Ravensburger Interactive Media and published by a consortium including Cryo Interactive and 1C Company, this digital adaptation of a board game sought to capitalize on a timeless formula while ambitiously attempting to scale its premise to a global stage. As a piece of its time, Money Mad represents a fascinating, if flawed, intersection of traditional board game design, early 3D rendering, and the perennial human fascination with capitalist accumulation. This review will argue that while Money Mad is a technically competent and occasionally charming digital board game, it is ultimately a prisoner of its own repetitive design and a stark reminder that not all analog experiences benefit from a digital translation.

Development History & Context

The turn of the millennium was a period of transition and experimentation in the gaming industry. Ravensburger Interactive Media, a branch of the renowned German board game and puzzle company, was actively exploring the digital frontier, translating its analog IP into PC experiences. Money Mad, known under a plethora of localized titles like Ruhm und Reichtum (Germany), Richesses Du Monde (France), and Oligopoly (elsewhere), was part of this push.

The vision was clear: to take the foundational mechanics of a proven winner—specifically, the property-trading formula popularized by Monopoly—and elevate it to a grander, global scale. The technological constraints of the era are evident. This was a time when 3D acceleration was becoming standard, but developers were still mastering its implementation for non-action genres. The game was built for Windows, requiring only a mouse for input, positioning it as an accessible, family-friendly title. The gaming landscape was dominated by ambitious sims and RTS games; Money Mad was a deliberate counterpoint, a digital hearth around which families could gather, albeit on a single computer screen. Its development was a bet on the enduring appeal of board games, even as the industry charged toward more complex digital-native experiences.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Money Mad dispenses with any pretense of a traditional narrative. There is no story-driven campaign, no characters with backstories, and no plot twists. Instead, its “narrative” is emergent, generated by the players’ actions on the global board. The premise is a pure, unadulterated power fantasy of capitalism: players are aspiring moguls, and their only goal is to amass a colossal industrial empire, drive all competitors into bankruptcy, and stand alone as the world’s wealthiest individual.

The characters are merely avatars, defined by simple cartoonish models and light animation. As noted by critics like GameStar, the “gelungene Comic-Look” (successful comic look) gave these avatars a pleasant, approachable charm. However, they are vessels, not personas. The dialogue is functional, limited to game events, transactions, and the taunts or deals between players.

Thematically, the game is a blunt instrument. It is a celebration, and perhaps a mild satire, of ruthless acquisition. The global setting—with players purchasing commodities like coffee, coal, and steel across continents—attempts to add a layer of geopolitical strategy, suggesting a tycoon-like depth. However, this thematic ambition is largely skin-deep. The game doesn’t critique the systems it portrays; it simply revels in them. The core theme is the thrill of the deal, the agony of a missed opportunity, and the Schadenfreude of bankrupting a friend. It is a digital manifestation of the same fantasies that have driven board games for over a century.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its heart, Money Mad is a dice-rolling, turn-based board game. The core loop is immediately familiar to anyone who has played Monopoly:

1. Roll the dice.

2. Move your token around the global board.

3. Land on a space and execute its action: buy a new resource, pay rent to an opponent, draw a chance card, or manage your industrial properties.

4. Pass the turn and repeat until one player achieves total financial domination.

The primary innovation is the shift from city streets to global resources. Instead of buying Park Place, you’re buying coffee plantations in South America or steel mills in Europe. This was the game’s key differentiator, aiming to evoke the feel of a managerial business sim layered atop a classic board game framework.

However, contemporary reviews were quick to identify the flaws in this system. German magazine PC Player pointed out that the “arg vielen Zufallsereignisse” (sheer number of random events) often felt more punishing than the actions of opponents, reducing strategic feeling. The AI, as noted by Gamekult, was a significant weakness; its “ratés de l’intelligence artificielle” (failures of artificial intelligence) made solo play a tedious affair of waiting through long computer turns for underwhelming decisions.

The UI is functional and mouse-driven, making it accessible. The “hot-seat” multiplayer support for up to six players was a standout feature, a relic of an era before ubiquitous online play. As the Russian outlet Absolute Games praised, this feature allowed for “massovyh igr za odnim kompyuterom” (mass games at one computer), positioning it as a party game for the pre-LAN era.

Ultimately, the mechanics are a double-edged sword. They successfully capture the simple, addictive rhythm of a board game but fail to evolve it meaningfully. The promised “corporate decisions” are shallow, and the gameplay quickly becomes repetitive. As PC Action (Germany) bluntly stated, for “hartgesottenen Spielerseelen” (hardcore player souls), it was “eher ein Graus” (more of a horror).

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Money Mad is a brightly colored, simplified depiction of Earth. The board is the centerpiece, rendered in an isometric 3D perspective that was standard for the time. The visual direction leans heavily into a cartoonish, approachable aesthetic. The various resource tiles and ports are distinct and easily readable, a crucial element for a game of this type.

The character models, while simple, are animated with a certain charm—their celebrations and disappointments add a touch of personality to the financial carnage. The sound design follows suit, featuring a “lockerer Big-Band-Sound” (loose big-band sound), as PC Player noted, which provides a lighthearted, jazzy backdrop to the cutthroat dealings. The Russian review also highlighted “zabavnaya ozvuchka” (amusing voice acting) as a plus, though it’s likely these elements were limited to event notifications and player reactions.

The atmosphere is not one of gritty realism but of a playful, almost satirical take on big business. The art and sound work in concert to soften the game’s ruthless core, making it palatable for a broader audience. It builds a world that is cheerful and competitive, though it lacks the depth and immersion of more ambitious titles from the same period.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its release in 2000, Money Mad received a lukewarm critical reception. With an average critics’ score of 54% on MobyGames, it was seen as a competent but unexceptional entry. Reviews were mixed: Absolute Games (70%) called it a “very high-quality version of the ancient Monopoly,” praising its hot-seat mode and balanced gameplay. On the other end, PC Games (Germany) scored it a mere 37%, declaring that board game conversions on PC “usually go down the drain.”

The consensus was that it was a faithful, sometimes enjoyable digital translation that was ultimately hamstrung by the limitations of its genre—namely, repetitive gameplay, weak AI, and a lack of meaningful innovation beyond its global reskin. It was a game best enjoyed with friends, as the solitary experience was a tedious slog.

Commercially, it faded into obscurity, overshadowed by more groundbreaking strategy games and the rising tide of digital distribution. Its legacy is minimal. It did not spawn a franchise nor is it cited as a direct influence on later titles. Its true legacy is as a museum piece, a perfectly preserved example of a specific moment in time when publishers were aggressively mining board game IP for PC sales. It exists today primarily on abandonware sites, remembered fondly by a small niche of players for its local multiplayer moments, but otherwise serving as a footnote in the history of both Cryo Interactive and digital board games.

Conclusion

Money Mad is a game of clear intentions and execution, yet ultimately unambitious results. It successfully translated a Monopoly-like experience to the digital realm with a charming presentation and solid support for local multiplayer. However, its failure to meaningfully deepen the gameplay mechanics, its reliance on overwhelming randomness, and its poor AI left it as a novelty rather than a necessity.

For historians and enthusiasts, it is a fascinating time capsule—a well-produced artifact from an era of transition. For the average player, it is a lesson that a bigger board does not necessarily mean a better game. Its place in video game history is secure not as a landmark title, but as a representative of a crowded and often forgotten genre of early digital adaptations, a competent but ultimately forgettable roll of the dice.