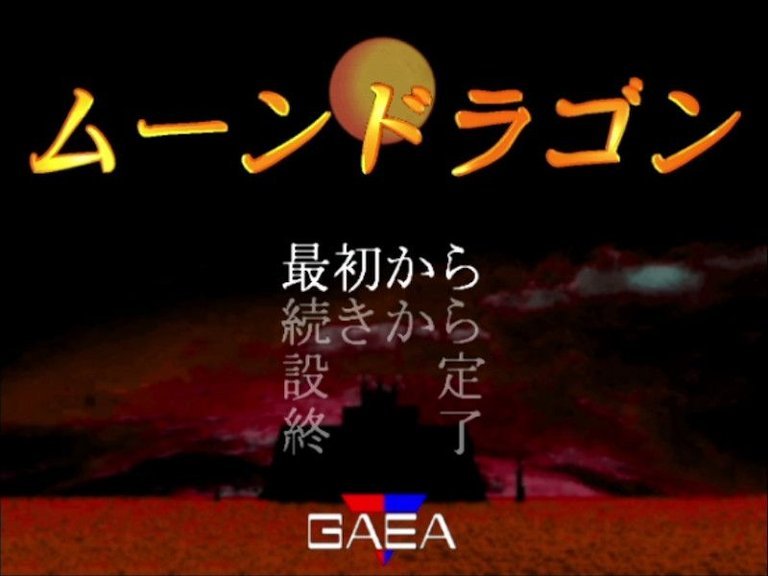

- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Gaea Entertainment

- Developer: Gaea Entertainment

- Genre: Role-playing (RPG)

- Perspective: 1st-person, 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Active Time Battle, Dungeon Crawling, Turn-based

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

Moon Dragon is a Japanese-style RPG following Rune and Blair as they search for their missing father. Upon arriving in Kukuru village, they learn about the Dragoyle, a monster that broke free from its magical seal. The game utilizes first-person dungeon crawling with pre-rendered CGI videos, Active Time Battle mechanics, and features full voice acting without subtitles. Outside of dungeon exploration, interactions are presented through static images with occasional effects.

Moon Dragon Guides & Walkthroughs

Moon Dragon Reviews & Reception

kotaku.com : Fantasy role playing game consisting of maps, enemy characters, items, and all 3D rendering.

Moon Dragon: Review

Introduction

In the twilight years of the 20th century, when console JRPGs dominated Japanese gaming and PC RPGs in the West often leaned toward Western epics, Moon Dragon (ムーンドラゴン) emerged as a curious, ambitious artifact. Released exclusively in Japan on August 30, 1997, by Gaea Entertainment, this Windows-exclusive title blended first-person dungeon crawling with traditional JRPG mechanics, wrapped in an anime aesthetic and powered by nascent FMV technology. Today, it survives as a relic—a niche, nearly forgotten entry in the genre’s history, preserved only through abandonware archives and fragmented online records. Moon Dragon is not a masterpiece by modern standards, nor was it a commercial titan upon release. Yet, its daring fusion of pre-rendered cinematics, turn-based combat, and full Japanese voice acting offers a fascinating glimpse into the experimental spirit of late-90s PC gaming, where developers pushed technological boundaries to craft immersive, albeit flawed, experiences. This review deconstructs Moon Dragon’s legacy, examining its narrative, gameplay, artistry, and historical context to argue that while it remains an obscure footnote, it stands as a testament to the era’s creative risks and the enduring appeal of anime-fantasy worlds.

Development History & Context

Moon Dragon was a product of Gaea Entertainment, a small Japanese studio operating in an era of rapid technological transition. Released for Windows 95/98, the game arrived at a pivotal moment: 1997 saw the launch of the PlayStation (which hosted epochal JRPGs like Final Fantasy VII), while PC gaming in Japan remained a niche space dominated by strategy simulations and eroge. Gaea Entertainment’s vision for Moon Dragon was explicitly cinematic, leveraging the burgeoning power of CD-ROMs to deliver pre-rendered CGI sequences—a novelty for PC RPGs, which typically relied on tile-based sprites or primitive 3D. The team’s ambition outstripped the era’s hardware constraints, however. With a minimum system requirement of a 75 MHz Intel Pentium CPU and 16 MB of RAM, the game struggled to balance its high-resolution FMV with responsive gameplay, leading to moments of sluggish performance and visual stuttering.

The gaming landscape of 1997 was saturated with JRPGs, but Moon Dragon carved a unique niche by merging two divergent trends: the first-person dungeon crawling of games like Eye of the Beholder and the anime-driven storytelling of console titles like * Tales of Phantasia. Its development was likely informed by the success of FMV experiments in Western PC games (e.g., *Phantasmagoria), but Gaea Entertainment transposed this framework onto a Japanese-fantasy template. The result was a game that felt technically audacious yet artistically conservative—a hybrid that appealed to neither console purists nor Western PC gamers. Its Japanese-only release and lack of localization further marginalized it, ensuring it would never reach the global audience it aimed for.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Moon Dragon’s narrative is a straightforward JRPG archetype, elevated only by its presentation and voice acting. The story centers on Rune (ルーン) and Blair (ブレア), a pair of siblings searching for their missing father. Their journey leads them to Kukuru village, where locals recount the legend of the Dragoyle—a terrifying monster magically sealed away centuries prior, only to have broken free. This premise, while derivative of Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy tropes, serves as a catalyst for a linear, character-driven quest. The dialogue, delivered entirely in Japanese with full voice acting (a rarity for 1997 PC RPGs), breathes life into the protagonists, though their personalities remain thinly sketched. Rune is portrayed as the determined elder sibling, while Blair acts as the cautious foil, their dynamic underscored by familial bonds.

The narrative unfolds primarily through non-interactive cutscenes and village dialogues, with branching dungeon paths offering the only player agency. Thematically, Moon Dragon explores familiar JRPG motifs: the corruption of ancient power, the burden of heroism, and the resilience of communities under siege. The Dragoyle’s escape symbolizes the fragility of order, while Rune and Blair’s search for their father mirrors the genre’s recurring theme of familial duty. However, the game never transcends its archetypal foundations. The lack of subtitles for its Japanese audio renders the plot incomprehensible to non-Japanese speakers, while the absence of side quests or complex character development leaves the narrative feeling perfunctory. It is a competent, if forgettable, fantasy yarn, buoyed solely by its vocal performances and atmospheric storytelling.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Moon Dragon’s gameplay is a dichotomy of ambition and limitation. Its core loop alternates between two distinct modes: guided first-person dungeon exploration and turn-based battles. The dungeon segments are the game’s most unconventional feature, employing pre-rendered CGI videos to create a pseudo-3D, on-rails experience. Players navigate linear corridors with branching intersections, where decisions are limited to choosing paths rather than exploring freely. This approach creates a cinematic, almost filmic progression, evoking the visual style of early FMV adventures. However, it sacrifices player agency, turning exploration into a passive experience punctuated by quick choices. Enemies and NPCs are represented as static still images, occasionally enhanced with simple effects (e.g., flickering shadows), further emphasizing the game’s reliance on pre-rendered assets over dynamic animation.

Combat follows the Active Time Battle (ATB) system, a staple of Square’s JRPGs popularized by Final Fantasy IV. Characters and enemies attack in real-time as ATB meters fill, requiring strategic timing and skill selection. The system is competently implemented but hampered by repetitive enemy designs and minimal party customization. Progression appears straightforward, with experience points gained from battles likely unlocking new abilities or equipment, though the sources provide no explicit details on levelling or stat improvements. The user interface features traditional menu structures for inventory and commands, but the lack of mouse support (per PCGamingWiki) makes navigation cumbersome. Innovative elements, like the seamless integration of FMV into gameplay, are undermined by technical hiccups—load times between dungeon segments and occasional lag during battles disrupt the flow. Ultimately, Moon Dragon’s gameplay feels like a compromise: too linear for exploration-focused players and too simplistic for combat enthusiasts.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Moon Dragon excels in atmosphere, crafting a cohesive fantasy world through its art direction and sound design. The setting is a classic J-RPG tapestry: verdant villages, shadowy dungeons, and looming monster threats. Kukuru village, the initial hub, is depicted with hand-painted backgrounds that evoke watercolor illustrations, while the Dragoyle’s lair is rendered with oppressive, CGI-driven darkness. The game’s visual style is uniformly anime-inspired, characterized by character designs reminiscent of 90s shojo series—large expressive eyes, flowing hair, and exaggerated emotive poses. This aesthetic extends to the UI, with menus adorned with decorative flourishes and kanji characters, reinforcing its Japanese cultural roots.

Sound design is the game’s crowning achievement. Full Japanese voice acting for all dialogues was a bold move for a 1997 PC RPG, adding emotional weight to even mundane exchanges. The audio quality is crisp, though the absence of subtitles alienates non-Japanese players. The soundtrack, while not detailed in the sources, likely features orchestral arrangements typical of the genre, swelling during dramatic moments and fading to ambient melodies during exploration. Sound effects—sword clashes, monster roars, and footfalls—are standard but effective. The pre-rendered CGI sequences, though technically limited by 1997 hardware, lend the game a cinematic grandeur, with sweeping camera pans and dynamic lighting that evoke the style of late-90s anime OVAs. Together, these elements create an immersive, albeit static, world that feels more like an interactive anime than a traditional game.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its release in 1997, Moon Dragon garnered little attention, either critically or commercially. Its Japanese exclusivity and PC platform limited its audience, and no major reviews or sales figures survive in the archives. MobyGames lists it with a “Moby Score” of n/a, and contemporary forums show minimal discussion. The game’s legacy is thus defined by its rarity and preservation. By the 2000s, it had faded into obscurity, cited only in obscure abandonware lists like MyAbandonware, where it holds a modest 4.5/5 rating based on two user votes. PCGamingWiki marks it as a “stub,” reflecting the lack of detailed documentation.

Influence on subsequent gaming is minimal. While its blend of FMV and JRPG mechanics prefigures modern cinematic RPGs (e.g., The Witcher 3), Moon Dragon did not directly inspire landmark titles. Its most significant contribution is as a historical artifact, preserved on platforms like the Internet Archive, where it remains playable for preservationists. The game’s failure to resonate highlights the challenges of niche, region-locked releases in an era of globalized gaming. Yet, its survival underscores a broader appreciation for experimental, mid-90s PC projects that pushed boundaries despite their flaws. Today, Moon Dragon is studied for its ambitious use of pre-rendered graphics and voice acting, serving as a case study in the risks and rewards of technological innovation in game development.

Conclusion

Moon Dragon is a product of its time—an earnest, if imperfect, attempt to merge JRPG traditions with cutting-edge PC technology. Its narrative is archetypal, its gameplay is divisive, and its accessibility is severely limited by language barriers. Yet, as a historical document, it is invaluable. The game’s bold use of pre-rendered CGI, full voice acting, and cinematic exploration demonstrates the creative risks developers took in the 1990s, when hardware constraints and niche markets fostered unique experiments. Its artistic direction, anchored by a cohesive anime-fantasy aesthetic and evocative sound design, transcends its technical limitations, creating an experience that is atmospheric, if not engaging.

In the pantheon of JRPG history, Moon Dragon will never rank alongside Chrono Trigger or Final Fantasy VII. It is a footnote—a relic of a bygone era of PC gaming. Yet, for preservationists and genre historians, it offers a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of interactive storytelling. Moon Dragon is, ultimately, a testament to the power of ambition over execution: a flawed, ambitious gem that reminds us that even forgotten games can illuminate the past. As we preserve titles like this, we ensure that the bold, if clumsy, steps taken by pioneers like Gaea Entertainment are not lost to time.