- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Moraffware

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Breakout, Paddle, Pong

Description

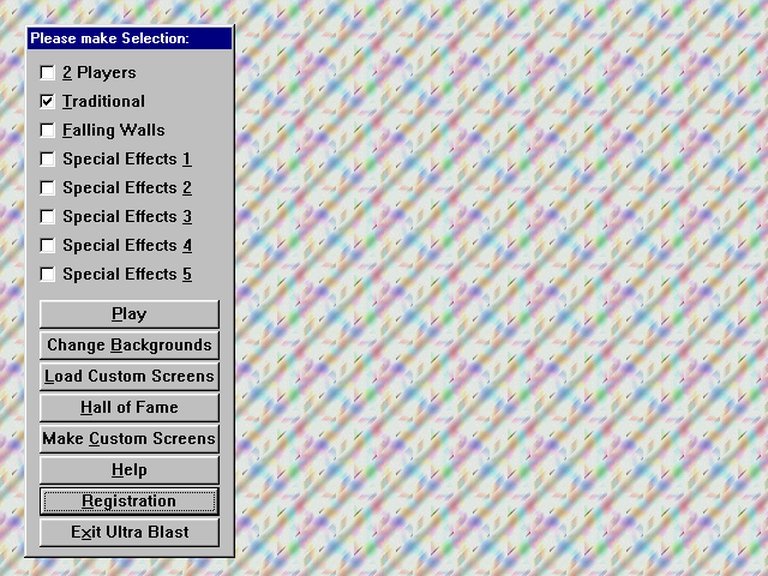

Moraff’s Ultra Blast is a 1995 Windows shareware game that serves as an updated and extended version of the earlier Moraff’s Blast I. It features three distinct Breakout-style modes—Traditional, Falling Walls, and Special Effects—where players use a mouse-controlled paddle to bounce a ball and destroy bricks with novel behaviors such as one-directional passage, spawning, movement, and ball-eating. With support for multiple color depths, sound effects, and top-ten score tracking, the shareware version includes 25 levels, while the full Ultra Blast II expands to over 100 levels and a screen creation tool, offering a versatile arcade experience for one or two players.

Gameplay Videos

Moraff’s Ultra Blast Free Download

Moraff’s Ultra Blast Reviews & Reception

themodernretrocorner.com : I welcome the changes that the developer made but what I am not thrilled with is the audio cues.

Moraff’s Ultra Blast: A Calculated Deflection in the Breakout Wars

Introduction: The Mouse That Roared

In the vast and varied ecosystem of 1990s PC gaming, few franchises embody the spirit of the prolific shareware developer quite like Steve Moraff’s catalog. While he is perhaps best remembered for the first-person RPG Moraff’s Dungeons of the Unforgiven or his suite of tile-based mahjong solitaires, his Moraff’s Blast series represents a dedicated, decades-long engagement with a single, foundational game concept: the ball-and-paddle “Breakout” or “Brickles” mechanic. Moraff’s Ultra Blast (1995), the Windows-focused iteration of this lineage, arrives not as a revolutionary leap but as a masterclass in iterative refinement and clever, almost subversive, design augmentation. It is a game that takes the rigid, left-to-right paddle constraint of its arcade ancestors and utterly dismantles it, transforming a predictable reflex tester into a spatial puzzle game. This review argues that Ultra Blast is a significant, if niche, artifact of the Windows 95 transition era—a title that leveraged new input paradigms and a shareware “try-before-you-buy” ethos to push subtle but meaningful innovations within one of gaming’s most ancient templates. Its legacy is not one of mass cultural impact, but of demonstrating how deep, systemic tweaks to a classic formula can create a fresh, intellectually demanding experience from familiar components.

Development History & Context: From DOS Card-Catalogues to Windows 95

To understand Ultra Blast, one must first understand its creator, Steve Moraff, and the ecosystem he operated within. As documented on the selectbutton wiki, Moraff was a pioneering shareware developer whose career began in the late 1980s. His company, initially Moraffware and later Software Diversions, Inc., was responsible for several “firsts”: Moraff’s Pinball (1989) is cited as the first VGA game, and he was an early adopter of distributing political texts with his games and running in high resolutions like 800×600. This context is crucial. Moraff was not a hobbyist tinkering in a garage; he was a keen observer of the IBM PC’s evolving capabilities, constantly pushing the boundaries of what was expected from a shareware title in terms of presentation and options.

Moraff’s Blast I debuted on DOS in 1991. The series, including Super Blast (1992), established a reliable, if conventional, Breakout foundation with several game modes. By 1995, the PC landscape was shifting dramatically. Windows 95 was the new dominant platform, offering a standardized GUI, mouse-centric interaction, and a color-rich, multimedia-friendly environment. Ultra Blast is explicitly a “updated and extended version… for Windows.” Its development was constrained and enabled by this transition. The jump from DOS to Windows meant moving from keyboard-driven, mode-13h graphics to a mouse-navigated, GDI-based environment that could natively support a stunning array of color depths—from 16 to “16 million colours”—as proudly listed on its MobyGames entry. This wasn’t just a port; it was a re-imagining built around the Windows 95 mouse and the new creative freedom of higher-resolution, textured displays.

The business model was quintessential shareware: a free, limited “taster game” with 25 levels, prompting registration to unlock the expanded Moraff’s Ultra Blast II with “at least one hundred levels and one hundred backgrounds” plus a “screen creation tool.” This model incentivized a strong core experience in the free version to drive sales, and Ultra Blast’s design is clearly structured with this in mind—its 25 levels are a curated showcase of its most novel mechanics, designed to tantalize the player with the promise of infinite user-generated content.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Aesthetics of Agency

Moraff’s Ultra Blast possesses no traditional narrative. There is no story, no characters, no dialogue. Its “thematic” content is entirely abstract, emerging from its systems and its presentation. The core theme is player agency and customization—both within the game’s rules and over its very appearance.

The most profound thematic statement is the radical expansion of paddle control. The classic Breakout formula shackles the player to a horizontal rail, reducing agency to a single axis of timing. Ultra Blast’s decision to allow the mouse-controlled paddle to move anywhere on the screen is a philosophical shift. It transforms the paddle from a passive reflector into an active, spatial tool. The player’s agency is no longer just about timing, but about positioning—a full 2D plane of potential intervention. This ignores the historical “gravity” of the genre and asks, “What if the player could solve this problem from any angle?”

This theme of customization extends to the game’s visual identity. The source material repeatedly highlights the ability to customize “bricks, backgrounds and wallpaper.” The default brick set, according to RGB Classic Games, “remind[s] of Spherejongg” (another 1995 Moraff title), linking its aesthetic to the developer’s broader work in tile-matching games. The backgrounds can be changed to “whatever you want.” This positions the game not as a fixed, authored artifact, but as a canvas. The “thematic” experience becomes one of personalization—your game, your bricks, your background. The registered version’s screen creation tool is the ultimate expression of this, moving from player customization to player authorship. The game’s underlying message is one of empowerment: here are powerful, novel mechanics; now make them your own.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Deconstructing the Arcade

The gameplay of Ultra Blast is a trio of distinct but interconnected modes, each exploring a different victory condition from the Breakout lineage, all filtered through its revolutionary control scheme and a suite of “novel features.”

1. Traditional Mode: The purest expression of the core loop. The goal is to destroy all bricks in the shortest time. Here, the free-roaming paddle is a subtle but powerful advantage, allowing for impossible bank shots and recovery from wild ball angles that would be unrecoverable in a linear-paddle game. It turns a race against time into a spatial efficiency puzzle.

2. Falling Walls Mode: A survival twist. Instead of a static field, rows of “walls” (brick layers) descend periodically, crushing the paddle if touched. The objective is longevity. The free paddle movement here becomes a vital escape mechanism, allowing the player to temporarily flee to the upper reaches of the screen to avoid an encroaching wall, creating tense vertical space management not seen in standard Breakout.

3. Special Effects Mode (The Crown Jewel): This is where Ultra Blast transcends being a mere variant and becomes a unique puzzle game in its own right. As noted by RGB Classic Games, the goal is not to score points but to “complete each level by destroying all of the non-permanent bricks.” This fundamental change forces precision and planning over chaos. The mode introduces a taxonomy of special bricks that dramatically alter the game’s logic:

* One-Way Bricks: The ball travels through them in only one direction (e.g., up but not down). This introduces directional puzzles where the ball’s path must be engineered to hit critical bricks from the correct angle.

* Spawner Bricks: Upon impact, these create new bricks, potentially filling the screen with obstacles—a risk/reward dynamic that can turn a clear path into a labyrinth.

* Moving Bricks: Shift position when hit, requiring players to anticipate their new locations and adapt shot plans on the fly.

* Ball-Eating Bricks: Destroy the ball on contact, acting as hazards to be avoided or used strategically to remove excess balls.

* Multi-Ball Bricks: Split the ball into four, increasing chaos but also offensive potential.

According to RGB Classic Games, there are “five versions of Special Effects which seem to have some relationship to their difficulty.” This implies curated sets of these mechanical bricks, creating a progressive difficulty curve based on puzzle complexity rather than just speed or brick count.

Core Systems Across All Modes:

* Paddle Physics: The mouse-controlled, omnidirectional paddle is the game’s foundational innovation. It removes the “lane” constraint, making every bounce angle theoretically possible via player positioning.

* Progression: Levels are discrete. In Traditional and Special Effects, completion of a level’s objective (clear bricks) advances the player. In Falling Walls, progression is measured in score/time survived.

* UI & Feedback: The game keeps top ten scores for each mode. Its most distinctive UI element is the audio announcer, a feature highlighted with bemusement by The Modern Retro Corner. It only chimes in upon ball loss, announcing the score or balls remaining. It’s a quirky, somewhat intrusive layer of feedback that feels of its time—a synthesized voice as a punitive punctuation mark.

* The Registered Promise: The mention of Ultra Blast II‘s screen creation tool is the carrot at the end of the shareware stick. It acknowledges that the game’s true longevity depends on community-created content, a forward-thinking model for the era.

Flaws & Limitations: The core loop, however innovative, remains a niche skill set. The “free paddle” can also be a crutch, potentially reducing the tension of “last-second saves” that define classic Breakout. The Special Effects mode, while brilliant, can become visually and spatially cluttered with too many active brick behaviors, leading to confusion. The audio design, save for the announcer, is described only as having “sound effects,” suggesting a functional but unremarkable aural landscape.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Customizable Cosmos

Ultra Blast does not build a world in a narrative sense; it builds an aesthetic sandbox. Its world is the playfield itself, defined by two primary customizable elements: bricks and backgrounds.

Visual Direction: The game leverages the Windows 95 era’s leap in color depth. Support for 16, 256, 65,536, and 16 million colors means the game runs on everything from a 16-color CGA display to a true-color SVGA monitor, ensuring accessibility but also showcasing the vibrancy of higher settings. The default brick set, as noted, has a distinctive look tied to Moraff’s other tile games (Spherejongg), suggesting a cohesive visual library across his products. The ability to replace these with user-designed graphics (and the promise of 100 backgrounds in the full version) turns the game’s look into a variable. The “textured backgrounds” and “spinning swirls and blinking eyes for balls” mentioned in the Internet Archive description hint at a playful, almost psychedelic abstract aesthetic more in line with a screensaver than a traditional arcade game. This is not the gritty, pixel-art future of Doom; it’s the customizable, user-friendly desktop aesthetic of the early web.

Sound Design: The soundscape is sparse. There are “sound effects” for ball collisions and brick destruction—functional, likely digitized bleeps and bloops. The defining audio feature is the announcer voice. The Modern Retro Corner candidly states: “the only time you will hear it is when you lose your ball and then the voice will tell you your score or how many balls are left. I applaud the effort put into the announcer voice but we could do without it.” This sums it up perfectly: it’s a charming, era-specific novelty that quickly becomes an annoying, un-skippable interruption. It adds zero gameplay value and actively disrupts the flow, a rare misstep in an otherwise focused design.

The atmosphere is thus one of customizable abstraction. It feels less like entering a designed world and more like loading a configurable widget. This aligns perfectly with the shareware ethos and the game’s emphasis on player-driven creation via the level editor.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Configured

Contemporary reception for Moraff’s Ultra Blast is effectively non-existent in the archival record. MobyGames lists no critic reviews and only three collectors. It was not a title that graced magazine cover discs or received mainstream press. Its audience was the shareware downloader, the BBS habitué, the player who browsed catalogs like those on Tucows. It was a deep cut within a deep cut—a Breakout game from a developer not known primarily for arcade action, on the nascent Windows platform.

Its legacy is twofold and modest:

-

A Showcase of the Windows 95 Shareware Aesthetic: Ultra Blast is a perfect time capsule of the mid-90s Windows shareware scene. It features: exhaustive configuration (colors, controls, graphics), a clear trial/registration split, reliance on the mouse as a primary input, and a graphical style that prioritizes clarity and customization over cinematic flair. It represents the “utility” side of gaming—software as a tool for personalized entertainment.

-

An Underground Influence on Puzzle-Breakout Design: While it left no direct, traceable footprint on major studio titles, its design DNA can be seen in the niche and independent scenes. The concept of a free-roaming paddle has appeared in various indie Breakout hybrids. The idea of bricks with directional properties and spawners prefigures the complex block behavior in modern puzzle games like Puzzle Quest or Meteos (albeit in a different genre). Most directly, its cousin Marble Blast Ultra (2006) shares the Moraff name and a marble-rolling mechanic but carries forward the spirit of a clean, customizable, physics-based puzzle game for a broad audience. Ultra Blast argued that the Breakout formula had untapped depth in spatial freedom and rule-bending bricks; a few developers later would listen.

Its current status is that of an abandonware curiosity. Preserved on sites like My Abandonware and the Internet Archive, it is accessible to retro enthusiasts willing to tinker with Windows 3.x/95 compatibility layers. Its lack of a strong online community or modern re-release keeps it firmly in the realm of historical footnotes and personal nostalgia. Yet, for those who discover it, it often comes as a revelation—a game that feels both archaic and strangely modern in its systemic cleverness.

Conclusion: The Perfect Paddle, The Perfect Pixel

Moraff’s Ultra Blast is not a lost masterpiece. It does not redefine its genre for the masses or tell a poignant story. Instead, it is a masterful piece of design craft. It takes a formula centuries old—hit a ball with a paddle—and asks, “What if the paddle wasn’t on a track?” The answer is a game that is simultaneously familiar and disorientingly new, where muscle memory must be discarded for spatial reasoning.

Its strengths are its brilliant, singular innovativeness (the free paddle) and its commitment to player expression (the graphics editor). Its weaknesses—a thin audio implementation, a lack of broad appeal, and a presentation that screams “1995 shareware”—are products of its time and purpose. It is a game made for a specific audience: the tinkerer, the puzzle-solver, the player who enjoys mucking about with options screens as much as playing.

In the grand tapestry of video game history, Moraff’s Ultra Blast is a single, vibrant thread in the “Breakout variants” section. It is a testament to the idea that even the most-played-out concepts can be reinvigorated not with 3D graphics or orchestral scores, but with a single, elegant question about player control. For that, it earns its place not on a podium, but in the respected, well-thumbed playbook of clever game design—a quiet,鼠标-controlled revolution in a box of shareware floppy disks. Its verdict is one of profound, niche significance: an essential study for students of iterative design and a delightful, hidden gem for those who believe that the deepest mechanics are often found in the oldest forms.