- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Idigicon Limited

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

More Arcade/Strategy Games is a 2003 Windows compilation from Idigicon Limited, part of its Family Fun range, that collects shareware and freeware titles into an interactive menu system. The menu features separate icons for ‘More Arcade Games’ and ‘Strategy Games’, each divided into multiple sections with dozens of games—such as Dragon Glide and Chess—some appearing in both groups, alongside trial software and DirectX 8.0 installation options, all presented with distinctive audio feedback.

More Arcade/Strategy Games Free Download

More Arcade/Strategy Games Reviews & Reception

comicbook.com : 2003 was a great year for video games.

More Arcade/Strategy Games: Review

Introduction: A Time Capsule of the Shareware Era

In the grand narrative of video game history, certain titles stand not for their innovation or critical acclaim, but as perfect, tangible artifacts of a specific moment in the industry’s evolution. More Arcade/Strategy Games, a 2003 compilation published by Idigicon Limited, is precisely such an artifact. It is not a game in the traditional sense; it is a museum, a flea market, and a digital time capsule rolled into a single CD-ROM. Released at the precise historical inflection point where broadband internet was beginning to displace shrink-wrapped shareware collections, this compilation represents the final, commodified gasp of a bygone era. One does not play More Arcade/Strategy Games to experience a unified creative vision. Instead, one examines it to understand the vast, sprawling, and often charmingly crude ecosystem of amateur and semi-professional PC development that thrived in the shadow of the industry’s blockbuster giants during the early 2000s. Its thesis is implicit: the golden age of the curated, physical collection of digital curiosities was ending, and this disc is one of its last, most comprehensive epitaphs.

Development History & Context: The Last Gasp of the Boxed Collection

The studio behind this endeavor, Idigicon Limited, was a UK-based publisher specializing in these “Family Fun” range compilations. Their business model was a direct descendant of the 1990s shareware boom popularized by companies like Apogee (3D Realms) and Epic MegaGames. The core concept was simple: acquire the rights to dozens, even hundreds, of inexpensive or freeware games—often developed by small teams or single individuals in their spare time—bundle them onto a CD, add a generic menu system, and sell the package at a low price point in software stores or via mail-order catalogs.

The technological context of 2003 is crucial. The dominant platforms were the Sony PlayStation 2, Nintendo GameCube, and Microsoft Xbox, with the Game Boy Advance leading the handheld market. High-speed internet was spreading but not ubiquitous; for many, a CD-ROM full of games was a treasure trove of instant entertainment. DirectX 8.0, included as a separate “Trial Software” icon on the menu, was a critical system component, and its bundling highlights the target audience: the less tech-savvy PC user who might need a driver update to run the included games. The compilation’s very existence speaks to a market segment still reliant on physical media and seeking a curated, low-cost entry into the vast world of PC gaming beyond the headline acts.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Anthology of Anticlimax

To speak of “narrative” or “thematic depth” in More Arcade/Strategy Games is to engage in a categorical exercise, as the product possesses none of these things as a whole. Its story is the story of its constituent parts, each a tiny, isolated narrative fragment.

- The Arcade Sections: Here, themes are primal and immediate. Brave Dwarves 2 offers a simple fantasy of subterranean treasure hunting. Charlie the Duck presents a whimsical, almost surreal platforming adventure. Dragon Glide (which appears in both sections) evokes the classic fantasy trope of the dragon rider. The majority, however, are abstract. Titles like AirXonix (a Qix clone), Bugatron (a Arkanoid-like), Lines, or Slider are pure, gameplay-centric exercises in pattern recognition and spatial reasoning. Their “narrative” is the cold logic of the game board and the escalating score.

- The Strategy Sections: The narratives here are slightly more formalized, often borrowing the lexicon of war, economics, or conquest. Battles in a Distant Desert or Battles On Distant Planets invoke sci-fi military fiction. Hollywood Mogul and Gazillionaire simulate the cutthroat world of business. Chess, Go (Gomoku), and classic board game adaptations like Risk (Turbo Risk, World Empire V) carry the implicit theme of abstract strategic conflict. Even the most complex, like Space Empires III, offer a grand narrative of interstellar empire-building, but it is a sandbox for the player’s own story, not a linear plot.

- The Shared Themes: Unifying both categories is a theme of democratization. These are games made not by large teams in glossy offices, but by passionate individuals or small groups working with limited tools (many are clearly built on simple 2D engines). Crazy Eggs, Cyber Mice Party Pack, and Shepherd Dogs Team suggest a desire to create family-friendly, accessible experiences. Others, like HaCKeR or Fiznik, hint at the hacker/cracker subculture of the era. The compilation is a testament to the “anyone can make a game” ethos that preceded the modern indie boom’s professionalization.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Museum of Mechanical Ideas

The gameplay landscape of More Arcade/Strategy Games is breathtakingly diverse, a veritable bestiary of interactive concepts, most drawn from well-established arcade and board game archetypes.

Core Arcade Gameplay Loops:

* Action/Shooters: 3D Shooter1/2, Astroship Evader, Saucer Attack, and Strayfire represent simple 2D/3D shooters with basic movement and firing mechanics. Hover Wars II adds a layer of vehicle control.

* Arcade Action/Puzzle: D-XBall and Bugatron are Breakout clones. Bubble Trouble and Smiling Bubbles are Puzzle Bobble derivatives. Air Hockey and Air Hockey replicate simple sports.

* Platformers/Adventures: Brave Dwarves 2, Dragon Fire, Dragon Jumper, and Rocknor’s Bad Day offer side-scrolling exploration with basic jumping and combat.

* Maze/Chase: AirXonix is a direct Qix variant. Pac-Man itself is not here, but its DNA is in AttackAttack and Al’s Home Antack.

* Abstract/Reaction: Ice Mania, Flaps, Silly Balls, and Snowball Fight test simple reflexes and pattern recognition.

Core Strategy Gameplay Loops:

* Turn-Based Tactics: Xenocide-style combat in ATTACK (not listed but implied by genre), Battle Fleet 1939, Depth Charge, and Warheads SE. These often involve grid-based movement and firing.

* Resource Management/Economic: Build City, Castle, Castles, Empire XP, and Simu-Trans focus on gathering resources (wood, stone, gold), constructing buildings, and managing a population or economy.

* Board Game Adaptations: Direct digital translations of Chess, Battleship (both Battle Ships and Battleship), Risk variants, Go (Gomoku), and Hex.

* 4X/Grand Strategy Lite: Space Empires III, Starships Unlimited, and World Empire V attempt the “explore, expand, exploit, exterminate” model on a galactic scale, albeit with primitive interfaces and AI compared to contemporary commercial titles.

* Unit Tactics: Pocket Tanks, Slay, and Soldiers Of Empires focus on balanced unit production and tactical positioning within a simple campaign or skirmish.

* Puzzle-Strategy Hybrids: Liquid War is a unique title where you control a “blob” of units trying to absorb the opponent’s blob, blending real-time strategy with a physical puzzle.

The Menu & Interface: A Study in Functional Rusticity

The entire experience is mediated by the “GT Menu” written by Gary Thomlinson. This is a simple, static menu with four large, non-movable icons. Its defining feature is an insistent, buzzing sound effect on cursor movement—a relic of an era when audio feedback was a primary means of confirming input in minimalist interfaces. The sub-menus for “More Arcade Games” and “Strategy Games” are divided into four “sections,” each a simple list of titles. The “Trial Software” section is just another list. There is no customization, no settings hub (settings are per-game), no unified save system. The interface is deliberately opaque, forcing the user to launch a game, exit it to return to the menu, and manually navigate back. This is not a flaw in design per se, but a perfectly honest representation of the technical capability and design philosophy of the time: functional, cheap, and attention firmly on the game list, not the shell.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Collage of Aesthetic Eras

More Arcade/Strategy Games is a deliberate pastiche of visual styles, reflecting the disparate eras and skill levels of its included software.

-

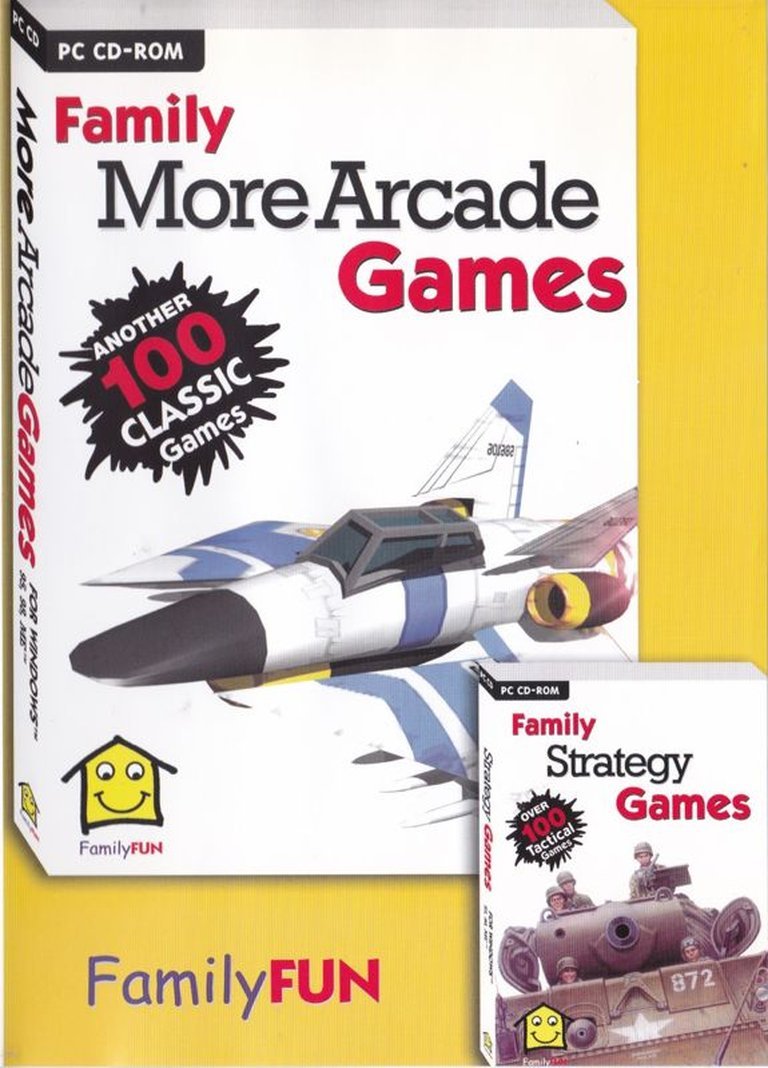

Visual Direction: The cover art, lifted from Idigicon’s More Arcade Games, features generic, cheerful, 3D-rendered characters—a stark, commercial contrast to the pixelated, 16-bit-inspired, or primitive 3D graphics within. The games themselves span a visual timeline:

- Retro 2D: Many arcade games use 256-color VGA or early SVGA graphics with chunky pixels (AirXonix, Lines, D-XBall), evoking the early 1990s.

- “Enhanced” 2D: Titles like Brave Dwarves 2 or Cyber Mice Party Pack use smoother, higher-resolution sprites and parallax scrolling, representing the late 1990s/early 2000s shareware “premium” aesthetic.

- Primitive 3D: 3D Dragon Castle, Teddy Adventures 3D, UFO Sokoban 3D employ simple textured polygons, flat shading, and low-poly models—the look of a hobbyist working with a nascent 3D API like DirectX 7 or 8. Space Empires III is a notable outlier, offering a somewhat more ambitious, if dated, sci-fi interface.

- Board Game Simplicity: The strategy section’s adaptations of chess and board games often use static 2D bitmaps or very basic isometric views.

The collective effect is one of profound temporal dislocation. You might play a game that looks like it’s from 1992, followed by one from 2001, then back to 1995. There is no coherent world, only a series of isolated visual dialects.

-

Sound Design: The soundscape is equally varied. The piercing, synthesized buzzer of the main menu is unforgettable. In-game audio ranges from:

- Beep-Boop Chiptunes: The classic PC speaker or AdLib/early Sound Blaster soundfonts of the simplest action games.

- MOD/S3M Tracker Music: More melodic, multi-channel tunes common in the European demo scene and shareware scene (Crazy Computers often has this feel).

- Recorded Samples: Low-bitrate, crunchy digitized sound effects for explosions, voice clips (“Game Over”), and occasional music loops, indicative of games leveraging the increasingly common Sound Blaster/AWE32.

- Silence: Many minimalist puzzle games have no music, only simple UI sounds.

The atmosphere is not immersive in a cinematic sense but is deeply nostalgic for those who remember the DIY sound of the pre-YouTube, demo scene era. It’s the sound of a teenager in a bedroom with FastTracker 2 and a copy of Blazing Pockets.

Reception & Legacy: A Collector’s Item, Not a Critical Darling

More Arcade/Strategy Games existed almost entirely outside the mainstream critical apparatus of 2003. Publications like PC Gamer or IGN were reviewing Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, Call of Duty, and Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. This compilation was not reviewed. Its “reception” is measured in unit sales in bargain bins and its subsequent status among retro computing collectors and archivists.

Its legacy is twofold:

-

As a Historical Artefact: For historians and preservationists, it is a invaluable snapshot. It contains dozens of titles that are otherwise lost to time, available only through abandonware sites or this very physical disc. It documents the sheer volume and variety of games being produced at the grassroots level—from competent (Crazy Eggs, Pocket Tanks) to baffling (Fiznik, Noname). It shows the persistent life of genres (Sokoban clones like Docker Sokoban and UFO Sokoban 3D) and mechanics (the Liero/Worms-inspired Worms-like play in Soldiers Of Empires or Slay) long before they were codified by major studios.

-

As the End of an Era: Its release in 2003 coincides with the peak and rapid decline of the boxed shareware compilation. The rise of high-speed internet, digital storefronts like Steam (which launched publicly in September 2003), and later, indie-focused platforms like itch.io and the modern proliferation of open-source and freeware, made the physical compilation obsolete. Why buy a CD with 100 games you don’t know when you could download demos instantly or, soon, buy single indie titles for a few dollars? More Arcade/Strategy Games is the dinosaur in the meteor’s path. The included “Trial Software” (3D Mini Golf, Mah Jong) is a last-ditch effort to add perceived value with commercial software trials, a practice that would also fade.

Its influence is diffuse. It did not spawn clones. Instead, its legacy lives on in the preservationist impulse. The very existence of databases like MobyGames, where this entry resides, is a response to the ephemerality these compilations both created and helped to mitigate. Modern retro compilation services like the Evercade or digital archives on platforms like GOG.com are the spiritual heirs to Idigicon’s mission, but with a curatorial, preservationist, and rights-cleared approach that these old compilations lacked.

Conclusion: A Definitive Verdict

More Arcade/Strategy Games is not a “good” game. It is not “bad” either. It is * objectively irrelevant* as a designed experience. Yet, as a historical document, it is * utterly fascinating and profoundly important*.

Its value lies entirely in its status as a primary source. It is a compressed snapshot of the vast, untamed PC gaming ecosystem of the late 1990s and early 2000s—the world that existed alongside The Sims and Half-Life. It preserves the work of Gary Thomlinson (menu designer) and over a hundred anonymous or semi-anonymous creators whose games would have vanished otherwise. It is a testament to the raw, unpolished, and fiercely creative energy that flowed through the shareware and freeware channels.

In the history of video games, it represents the commercial terminus of the shareware compilation model. It was released just as the industry was pivoting decisively toward digital distribution and the professionalization of independent development. To play through it is to walk through a ghost town of game development, where the buildings (the games) are in various states of repair, and the only constant is the buzzing, static menu that calls you to the next, completely unpredictable experience.

Final Verdict: 6/10 as a “product,” 10/10 as a historical archive. It belongs in the collection of every serious student of game history, not for its quality, but for its shocking, comprehensive, and honest representation of an entire stratum of our medium’s past. It is the gaming equivalent of a well-preserved time capsule from a bustling, chaotic, and hopeful era that was ending the very year this CD hit the shelves.