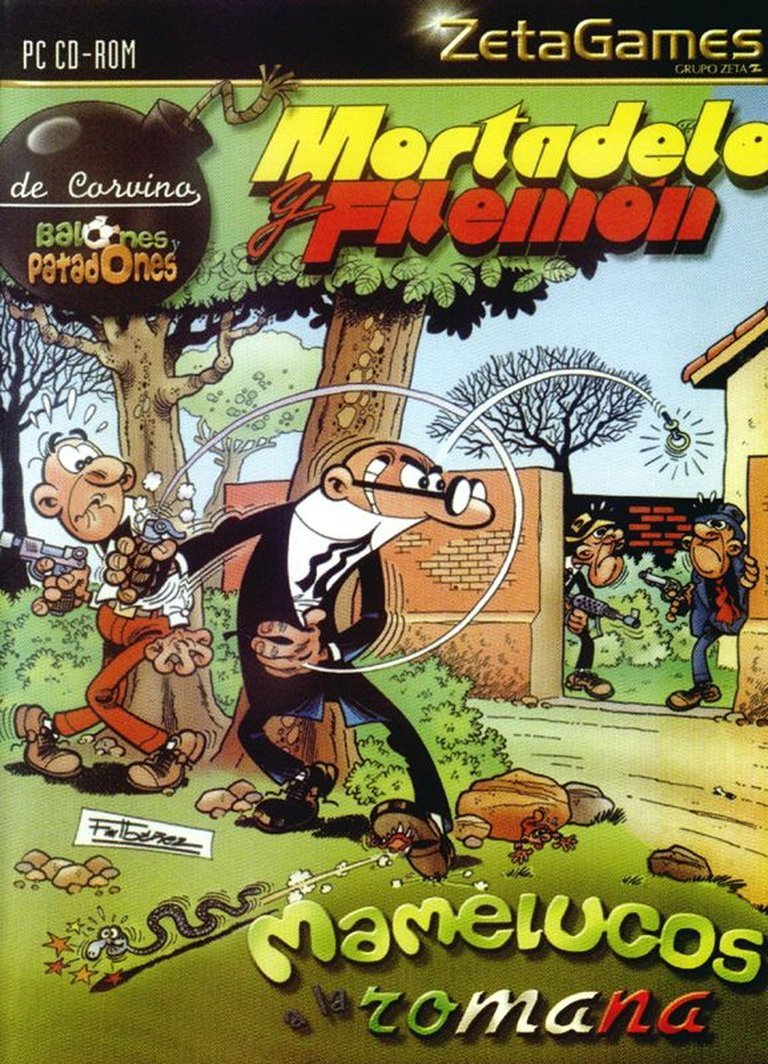

- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Zeta Multimedia S.A.

- Developer: Alcachofa Soft S.L.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Co-op, LAN, Online Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Point-and-click

- Setting: Italy, Modern

- Average Score: 79/100

Description

In ‘Mortadelo y Filemón: Mamelucos a la Romana’, the bumbling secret agents Mortadelo and Filemón pursue the mafia boss Vito Corvino, who has fled to Rome after his failed plot to sabotage the football World Cup in the previous game ‘Balones y Patadones’. As they navigate the ancient city, the duo must navigate espionage intrigue by allying with a rival gangster, staging an opera performance, eliminating a ruthless thug, and infiltrating Corvino’s secret lair, all while dealing with rival pursuers in this classic point-and-click adventure inspired by the iconic Spanish comic series, featuring hand-drawn 2D graphics and a unique multiplayer mode.

Where to Buy Mortadelo y Filemón: Mamelucos a la Romana

PC

Guides & Walkthroughs

Mortadelo y Filemón: Mamelucos a la Romana: Review

Introduction

Imagine chasing a flamboyant mafia don through the sun-drenched streets of Rome, dodging opera divas and shady gangsters while your bumbling secret agent partner turns every gadget into a slapstick disaster—this is the chaotic charm of Mortadelo y Filemón: Mamelucos a la Romana. Rooted in the iconic Spanish comic series by Francisco Ibáñez, which has tickled the funny bones of generations since 1958, this 2003 point-and-click adventure captures the essence of the hapless spies Mortadelo and Filemón in their eternal quest to save the world through absurdity rather than competence. As part of a beloved franchise that blends espionage parody with cartoonish humor, the game stands as a testament to how comics can leap from page to pixel, preserving a cultural touchstone for Spanish-speaking audiences. My thesis: While its dated mechanics and niche appeal may frustrate modern players, Mamelucos a la Romana excels as a faithful, laugh-out-loud tribute to its source material, offering a multiplayer twist that elevates it beyond typical adventure fare, securing its spot as a quirky gem in the history of licensed adaptations.

Development History & Context

Alcachofa Soft S.L., a modest Spanish studio founded in the late 1990s, spearheaded the development of Mortadelo y Filemón: Mamelucos a la Romana, building on their prior work in the franchise like Operación Moscú (2001) and the prequel Balones y Patadones (2003). The studio’s vision was clear: translate the manic energy of Ibáñez’s comics—known for over-the-top disguises, pun-filled dialogue, and visual gags—into interactive form without diluting the humor. Directed by Emilio de Paz, who also handled music and animation oversight, the team aimed to create a “living comic” that honored the series’ roots while experimenting with cooperative play. Cover artwork by Ibáñez himself ensured authenticity, bridging the gap between print and digital.

Released in 2003 amid a transitional era for PC gaming, the title grappled with technological constraints typical of early-2000s Spanish development. Running on Windows XP-era hardware with just 128 MB RAM recommended, it stuck to 2D hand-drawn sprites and pre-rendered backgrounds, evoking the golden age of adventures like LucasArts’ Sam & Max Hit the Road (1993) rather than embracing the 3D revolution seen in contemporaries like Beyond Good & Evil (2003). This choice was pragmatic—Spain’s gaming industry was still emerging, dwarfed by U.S. and Japanese giants, and budgets for licensed titles were tight. Zeta Multimedia S.A., the publisher, targeted a domestic audience hungry for localized content, as global hits like The Sims dominated but rarely catered to Spanish humor.

The broader landscape was one of genre fatigue for point-and-clicks; by 2003, the adventure market had shifted toward action hybrids (Tomb Raider sequels) or narrative-driven epics (Myst III). Yet, in Europe, especially Spain, comic adaptations thrived—think Asterix games or Tintin ports—filling a void for culturally resonant entertainment. Mamelucos arrived as a sequel in spirit, combinable with Balones y Patadones to unlock La Banda de Corvino, a move that encouraged replayability and series loyalty. Its multiplayer mode, allowing LAN or internet co-op where one player controls Mortadelo and the other Filemón, was visionary for the time, predating widespread online adventures and reflecting the era’s budding interest in social gaming, though limited by dial-up speeds and no voice chat beyond the in-game “Zapatófono.”

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Mamelucos a la Romana weaves a detective-mystery tale laced with spy-espionage tropes, picking up directly from Balones y Patadones. The plot kicks off with the T.I.A. (Técnicos de Investigación Aeroterráquea, a parody of bumbling intelligence agencies) tasking Mortadelo and Filemón to capture Vito Corvino, the mafia overlord whose World Cup sabotage plot was foiled. Fleeing to his Roman roots, Corvino—now hunted by the FBI for “misappropriating White House furniture” and Spain’s CESID—hides in a labyrinth of opera houses, back alleys, and secret lairs. The duo must navigate this underworld: striking a deal with a rival gangster (the enigmatic “Padrino”), enduring a full opera performance to gather intel, assassinating a thug named “El Napolitano,” and infiltrating Corvino’s hideout. What starts as a straightforward pursuit spirals into farce, with subplots involving absurd disguises (Mortadelo as a tenor or sculptor) and chases through Vatican-adjacent streets.

Characters are the beating heart, drawn straight from Ibáñez’s pages with exaggerated flair. Mortadelo, the master of disguise and perpetual screw-up, voiced by Miguel Ángel Manrique, embodies chaotic optimism—his antics, like using an aspiradora (vacuum) as a weapon, drive the comedy. Filemón Pi, the straight man (Roberto Cuenca Martínez), fumes through the mayhem, highlighting the duo’s yin-yang dynamic. Supporting cast shines: the hot-tempered “Súper” (Antonio Villar), the mad-scientist Professor Bacterio (Carlos del Pino), and villains like Vito Corvino (David García Vázquez) and Luca Ilionki (Miguel Ángel Montero), all dubbed by a 18-actor ensemble at Creativos Multimedia under de Paz’s direction. Dialogue crackles with Spanish wordplay—puns on “mamelucos” (fools in Roman attire) and football nods—often stretching conversations to 10 minutes, as noted in Russian localization reviews, blending exposition with rapid-fire banter that elicits “unforced smiles.”

Thematically, the game parodies mafia tropes (The Godfather via “Padrino” deals) and espionage clichés (James Bond gadgets gone wrong), underscoring themes of incompetence amid high stakes. Rome’s setting amplifies cultural satire: art (sculpting heads from trash), opera (a full session as puzzle), and soccer (Corvino’s lingering threat to “leave the world without football”). Underlying it all is Ibáñez’s anti-authoritarian humor—bureaucrats and criminals alike are fools—promoting resilience through laughter. When combined with the prequel, an alternate ending in La Banda de Corvino ties themes of persistence, but standalone, it resolves neatly, emphasizing friendship’s triumph over villainy. Flaws emerge in pacing; extended dialogues, while funny, can feel bloated, and the narrative’s linearity limits replay value beyond co-op.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

As a classic point-and-click adventure, Mamelucos a la Romana revolves around exploration, inventory puzzles, and dialogue trees, with players switching between Mortadelo and Filemón via a top-right UI toggle—a mechanic that adds strategic depth, as each character’s “personality” affects interactions (e.g., Mortadelo’s charm unlocks disguises, Filemón’s caution spots clues). Core loops involve scouring hand-drawn scenes for hotspots: in Rome’s streets, click alleys for a palanca (crowbar) or pera (pear) from trash; combine items like a tubo (tube) from a licorería with a ventilador (fan) to craft gadgets. Puzzles escalate cleverly—sculpting El Napolitano’s head requires gathering references (talking to a matón, photographing the target), blending observation with absurdity, like using a cuchillo (knife) from a thug to “kill” a prop.

Combat is minimal, more comedic set-pieces than mechanics; “battles” involve timed chases or QTE-style failures, like evading guards with pratfalls. Character progression is light—no levels, but inventory grows (up to dozens of items), and disguises evolve narratively. The UI is straightforward: inventory drag-and-drop, context-sensitive cursors, and a Zapatófono chat for multiplayer, where co-op players coordinate in real-time (e.g., one distracts while the other sneaks). Innovations shine here—LAN/internet co-op was rare for adventures, fostering emergent humor as friends botch puzzles together. Flaws abound: pixel-hunting frustrates (clues like the pera hide in cluttered backgrounds), and some puzzles feel obtuse without hints, echoing 90s LucasArts but without SCUMM’s polish. No save-anywhere system risks progress loss, and controls (mouse-only) feel clunky on modern setups. Still, the 3-5 hour runtime suits quick sessions, with co-op extending play to collaborative chaos.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Rome pulses as a vibrant, caricatured playground, blending historical nods (Vatican alleys, opera houses) with Ibáñez’s whimsical flair—think Colosseum shadows hiding mafia dens, or street vendors peddling plot-critical absurdities. Atmosphere drips with satirical tension: sunlit piazzas turn treacherous with lurking goons, and interiors like the Ristoranti evoke Goodfellas parody via flickering candles and whispered threats. World-building is intimate, not expansive; scenes loop via quick-travel (double-click hotspots), building immersion through detail—graffiti puns, soccer chants from hinchas (fans), and cultural Easter eggs like El Padrino’s operatic rants.

Visuals, in 2D hand-drawn style circa 1996-97, prioritize comic fidelity over innovation: cel-shaded characters bounce with exaggerated animations (Mortadelo’s rubbery disguises), backed by static but richly textured backgrounds. It’s “sympathetic but no more,” as one review quips—charming for fans, dated for others, with no 3D polish. Sound design elevates it: full Spanish voice acting by a stellar cast delivers punchy, ad-libbed humor (Bacterio’s 10-minute intros are gold), synced to lip movements for liveliness. Emilio de Paz’s score mixes jaunty orchestral swells for chases with tense strings for stealth, punctuated by cartoon SFX—boings for falls, splats for gags. Opera sequences shine, with José Perea’s tenor arias adding theatrical flair. Overall, these elements forge a cozy, immersive bubble: visuals and audio reinforce the comic’s levity, making Rome feel like a playable panel from Ibáñez’s strip, though low-res textures show age on HD displays.

Reception & Legacy

Upon 2003 launch, Mamelucos a la Romana garnered middling critical reception, averaging 58% from sparse reviews—60% from Aventura y Cía, praising its humor but decrying unfair comparisons to giants like Day of the Tentacle; 56% from Absolute Games (AG.ru), lauding witty Russian localization and voice work but critiquing “1990s-level” graphics. Players were harsher, with a lone MobyGames rating of 1.3/5, likely due to puzzle frustration. Commercially, it succeeded modestly in Spain, bundled with Balones y Patadones for 17.95€, appealing to comic fans amid a market favoring AAA titles. No U.S. release limited global reach, but it sold steadily via CD-ROM.

Reputation evolved positively with re-releases: a 2019 Windows update as part of La Banda de Corvino, and 2024 Steam port by Erbe Software (66% off at €1.69), earning three “Very Positive” user reviews for nostalgia and co-op charm. Legacy lies in preserving Spanish gaming heritage—part of a 10+ game series spanning 1989’s Safari Callejero to mobile spin-offs like Armafollón (2008). It influenced local devs, inspiring comic adaptations (Una Aventura de Cine, 2004) and co-op experiments in adventures. Globally, it underscores licensed games’ niche power, akin to Asterix titles, and highlights multiplayer’s untapped potential in narratives. While not revolutionary, its endurance on platforms like GOG Dreamlist cements it as a cult favorite, influencing modern remasters of classics like Broken Sword.

Conclusion

Mortadelo y Filemón: Mamelucos a la Romana distills the franchise’s slapstick soul into a compact, co-op-enabled adventure, blending sharp satire, memorable characters, and puzzle-driven hijinks against Rome’s chaotic canvas. Its 2D charm and voice acting shine, though dated mechanics and obtuse challenges temper the fun for newcomers. In video game history, it occupies a endearing corner: a love letter to Ibáñez’s comics that, despite modest impact, endures as a beacon for cultural adaptations and early online play. Verdict: Essential for Spanish humor enthusiasts or co-op seekers—7/10. Fire up the Steam port with a friend, and let the mameluco madness ensue.