- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

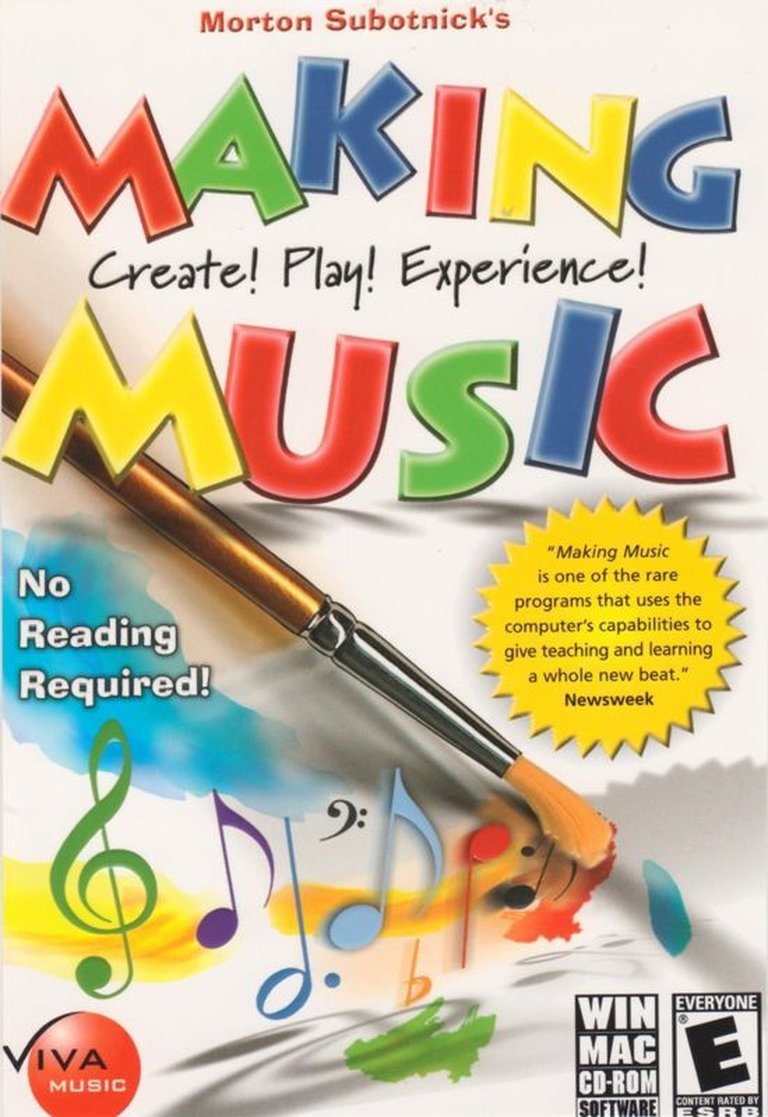

- Publisher: The Voyager Company, Viva Media, LLC

- Developer: Morton Subotnick

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Music, rhythm

- Average Score: 86/100

Description

Morton Subotnick’s Making Music is an educational edutainment game designed for children aged 8 and up, transforming music creation into an intuitive visual experience akin to finger-painting or drawing with crayons. Set in a digital workshop environment, players explore interactive tools such as dragging melody blocks, painting notes on a canvas, selecting from a palette of classic and exotic instruments, and composing songs with birds and eggs representing notes and rhythms, while also engaging in listening challenges to identify similarities, differences, and patterns in music.

Morton Subotnick’s Making Music Free Download

Guides & Walkthroughs

Morton Subotnick’s Making Music: Review

Introduction

Imagine a world where composing music feels as intuitive and joyful as smearing finger-paints across a canvas—where children, armed only with a mouse and boundless curiosity, can orchestrate symphonies without ever touching a piano key. Released in 1995, Morton Subotnick’s Making Music was a groundbreaking edutainment title that democratized music creation for young minds, transforming the abstract art of composition into a tactile, visual playground. As the inaugural entry in Subotnick’s influential music education series—which would later expand to include Making More Music, Hearing Music, and Playing Music—this CD-ROM gem arrived during the explosive rise of multimedia computing, positioning itself as a bridge between classical music theory and the digital age. Its legacy endures not just as a relic of 1990s educational software but as a visionary tool that empowered kids to “paint” sounds, fostering creativity in an era when computers were just beginning to hum with possibility. In this review, I argue that Making Music remains a seminal work in game-based learning, flawlessly blending pedagogy with play to make music education accessible, fun, and profoundly innovative.

Development History & Context

The development of Morton Subotnick’s Making Music was deeply rooted in the creative ethos of its titular composer, Morton Subotnick, a trailblazing figure in electronic and interactive music since the 1960s. Subotnick, known for pioneering synthesizer works like Silver Apples of the Moon (1967), envisioned this software as an extension of his lifelong mission to make music composition as approachable as visual arts for children. As he himself stated, “In Making Music, I set out to offer the young child the same experience in creating music that they already had in visual arts, using finger-paints or crayons.” This philosophy drove the project’s core design, emphasizing intuitive interfaces over rote instruction.

Published initially by The Voyager Company—a boutique firm renowned for high-brow interactive CD-ROMs like Laurie Anderson’s Puppet Motel—the game was crafted in a collaborative effort involving 41 credited individuals. Subotnick handled the composition, recording, and editing of all program sounds and music, infusing the title with his avant-garde sensibilities. Programmer Mark Coniglio, a frequent collaborator in interactive media, built the underlying engine, while producer Jane Wheeler oversaw the integration of educational elements. Illustration and art direction fell to William Nelson, whose whimsical visuals brought Subotnick’s abstract concepts to life. Additional contributors included audio engineers like Chris Burke and Rex C. Arthur, and even children’s voices from Pierce and Mary Ellen Cravens for on-screen help narration. Photographers Bruce Hamilton and James McGoon captured real-world images of instruments, grounding the digital experience in tangible reality.

The technological constraints of the mid-1990s profoundly shaped the game’s form. Released on CD-ROM for Macintosh (requiring System 7 or later, a 68030 processor, 5MB RAM, and a color display) and Windows 3.1/95 (16-bit version), Making Music leveraged the era’s burgeoning multimedia capabilities—MIDI sound support, basic drag-and-drop interfaces, and 640×480 resolutions—but was limited by hardware. No 3D graphics or real-time audio synthesis were feasible; instead, the game relied on pre-recorded samples and simple animations, with mouse input as the sole control method. Storage was a premium, with the hybrid disc format allowing cross-platform compatibility, though it meant compromises like compressed audio to fit exotic instrument sounds (e.g., dombak percussion or marimba).

The gaming landscape of 1995 was a fertile ground for edutainment. This was the heyday of CD-ROM “infotainment,” with titles like The Oregon Trail and Myst proving interactive media could educate and entertain. Educational software boomed as home computers proliferated—Apple’s Macintosh was a staple in schools, and Windows 95 promised mainstream accessibility. Publishers like Voyager targeted affluent, tech-savvy parents seeking “whiz-kid” tools, amid a post-Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? surge in learning games. Subotnick’s project fit perfectly into this niche, differentiating itself from drill-based math apps by focusing on the arts. An unreleased port to Bandai’s Pippin Atmark console (announced in 1996 catalogs) hinted at ambitions for console expansion, but platform limitations stalled it. Later re-releases by Viva Media in 2003 and updated editions by Alfred Music in 2008 (for Mac OS X and Windows XP/Vista/7) extended its life, adapting to classroom and home use with minor enhancements like improved compatibility.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Morton Subotnick’s Making Music eschews traditional narrative structures—no protagonists, no overarching plot, no branching storylines—in favor of an open-ended, exploratory framework that prioritizes experiential learning. At its heart, the “narrative” is one of discovery: players, positioned in a first-person interface as young composers, navigate a vibrant digital studio where music emerges as a living, malleable entity. There’s no scripted dialogue beyond helpful voiceovers from children (voiced by talents like Joaquin Dudelczyk and Jacob Subotnick) that guide users through modules with encouraging phrases like explanations of tools or celebratory affirmations upon successful creations. These audio cues, recorded by real kids, add a layer of relatability, making the experience feel like a collaborative jam session with peers rather than a solitary lecture.

Thematically, the game delves deeply into the democratization of creativity, portraying music not as an elite skill requiring years of practice but as an innate, playful extension of childhood imagination. Subotnick’s vision shines through in motifs of visual-auditory synergy: notes become colorful blocks to stack, rhythms manifest as eggs laid by birds, and melodies “paint” across canvases like abstract art. This mirrors broader themes in Subotnick’s oeuvre, where electronic music breaks free from notation’s rigidity—here, it’s a rebellion against the gatekeeping of sheet music, empowering users (targeted at ages 8 and up, but accessible to toddlers with supervision) to experiment without fear of “wrong” notes.

Underlying these is a profound emphasis on sensory integration and cognitive development. Modules like “Same or Different” encourage auditory discrimination, teaching subtle concepts like pitch variation (higher/lower) or sequence reversal through trial-and-error listening games. Themes of iteration and remix culture emerge in “Mix and Match,” where players swap melodies and rhythms, foreshadowing modern music production software like GarageBand. There’s no villain or conflict; instead, the “antagonist” is the blank canvas of silence, overcome through joyful persistence. Children’s images—photographed from diverse models like Amos Douglas and Maria Gjerdrum—pepper the interface, reinforcing inclusivity and the idea that music-making is a universal language. In an era when gender and racial barriers persisted in classical music, this subtle representation plants seeds of equity. Overall, the game’s themes coalesce into a manifesto for artistic liberation: music as finger-paint, not fortress.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Making Music revolves around modular gameplay loops that blend creation, experimentation, and ear-training into seamless, rewarding cycles. The single-player experience unfolds in a central hub—a colorful, intuitive desktop-like interface accessible via mouse clicks—where users can dive into eight primary activities or summon contextual help via a question-mark icon for narrated explanations. No timers or scores enforce progression; instead, the loop is one of build-listen-refine-share, with save functions allowing compositions to be stored and revisited, encouraging iterative play sessions that last from minutes to hours.

The creative backbone is the Building Blocks module, a drag-and-drop system where players construct melodies by stacking visualized note blocks (colored shapes representing pitches and durations). It’s akin to digital Legos: snap blocks together to form sequences, then hit play to hear the result. This introduces basic harmony without overwhelming theory, with loops forming as users test, tweak, and expand their “towers” of sound. Complementing this is Making Music, the game’s metaphorical heart—a canvas where notes are “painted” freestyle with a brush tool, turning composition into abstract art. Players smear pitches across a timeline, layer rhythms, and playback instantly, saving works as digital masterpieces. The loop here is purely expressive: create wildly, listen critically, edit intuitively.

Instrument selection via the Sound Palette adds depth to these systems, offering a library of 20+ samples from classical (piano, violin) to exotic (dombak, tom-tom) instruments, photographed realistically for immersion. Assign sounds to melodies, and the loop evolves into sonic experimentation—swap a flute for a trumpet mid-composition to hear timbral shifts. Melody & Rhythm Maker innovates with a whimsical metaphor: birds perch on wires as notes (position dictating pitch), dropping eggs as rhythmic hits. Players arrange avian ensembles to craft songs, blending strategy (avian positioning) with whimsy, and save outputs for later use. The remix-focused Mix and Match lets users dissect pre-made or custom pieces, swapping elements like mad scientists, fostering a loop of deconstruction and recombination.

On the educational side, listening games provide structured loops: Same or Different plays two snippets for sameness judgment; Find the Same challenges identification among three; Name That Difference quizzes on variations like inversion. These are quick, feedback-rich cycles—correct answers elicit cheerful voice responses, incorrect ones gently replay for learning. UI is a standout: clean, icon-driven menus with hover-audio help minimize frustration, though 1990s resolutions occasionally clutter screens. Flaws include limited undo functions (a single step in some modules) and no multiplayer sharing beyond saving files, but innovations like visual-auditory syncing prefigure tools in modern apps like Soundtrap. Character progression is absent, replaced by skill-building through repetition—players “level up” intuitively as their ear and creativity sharpen. Overall, the systems cohere into a flawless edutainment loop: accessible entry, deep mastery, zero barriers.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The “world” of Making Music is a cozy, fantastical atelier—a boundless digital studio unbound by physical laws, where soundscapes bloom from imagination. There’s no expansive lore or lore-heavy setting; instead, the environment is a metaphorical music lab, with modules as interconnected rooms in a child’s dreamlike workshop. Atmosphere is playful and inviting, evoking a sunlit classroom crossed with an avant-garde gallery—soft gradients and open spaces encourage lingering exploration without claustrophobia.

Visually, art direction by William Nelson crafts a vibrant, hand-illustrated aesthetic tailored to young eyes: bold primaries dominate, with whimsical icons like perching birds or paint-splattered canvases animating subtly under mouse interaction. Real photographs of instruments (e.g., gleaming trumpets, textured banjos) ground the abstraction, while diverse children’s portraits add warmth and representation. The 640×480 canvas feels era-appropriate—charming in its simplicity, though modern eyes might note pixelated edges or static elements. These visuals contribute immensely to immersion, making abstract concepts (pitch as height, rhythm as pattern) immediately graspable, turning potential confusion into delight.

Sound design, overseen by Subotnick, is the game’s true virtuoso. All audio—program music, effects, and help narration—is composed, recorded, and edited by the maestro himself, using high-fidelity samples that punch above the MIDI-era weight. Classic instruments resonate with authenticity (violin’s warm sustain, marimba’s crystalline ping), while exotic ones like the dombak introduce global flavors, broadening cultural horizons. Playback is responsive, with layered mixes creating rich polyphony from simple inputs. Voice acting from child performers adds an endearing, motivational layer—explanations are clear and enthusiastic, reinforcing the theme of peer-guided learning. Ambient cues, like subtle chimes on tool selection, enhance flow, while the absence of intrusive music ensures player creations shine. Together, art and sound forge a multisensory haven: visuals guide the hand, audio rewards the ear, culminating in an experience where the “world” feels alive with potential, profoundly elevating the educational core.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its 1995 launch, Morton Subotnick’s Making Music garnered modest but positive attention in niche edutainment circles, though comprehensive critic reviews are scarce—a testament to the era’s fragmented coverage of non-blockbuster software. Metacritic lists no aggregated scores, and sites like IGN note its independent roots without formal ratings. Player feedback, however, glows: MobyGames reports an average 4.3/5 from two ratings, praising its intuitive fun and educational value. Parents and teachers lauded its accessibility in early adopter communities, with abandonware archives like Internet Archive preserving it as a beloved relic. Commercially, it succeeded modestly via Voyager’s direct sales and school bundles, spawning the series (e.g., Hearing Music in 2004) and re-releases up to 2008’s classroom editions. The aborted Pippin port underscores untapped console potential, but CD-ROM sales aligned with the edutainment boom—millions of units industry-wide, though exact figures remain elusive.

Over time, its reputation has evolved from “innovative kids’ tool” to historical pioneer. In the 2000s, it influenced software like Apple’s Kid Pix extensions and early GarageBand prototypes, emphasizing visual composition interfaces. By the 2010s, as music education digitized, echoes appeared in apps like Incredibox (block-based beats) and Figure by Propellerhead (gesture-driven synths), proving Subotnick’s visual metaphor prescient. Its legacy in the industry is subtle yet seismic: it helped legitimize edutainment as “gaming,” paving the way for titles like Rock Band (rhythm education via play) and broader STEM/STEAM initiatives. In video game history, it occupies a vital niche—overlooked by AAA retrospectives but essential for understanding how interactive media humanized the arts, influencing modern tools from MuseScore to AI composers. Collected by just four MobyGames users today, its scarcity belies enduring impact: a quiet revolution in creative software.

Conclusion

Morton Subotnick’s Making Music is a masterclass in purposeful simplicity, weaving Subotnick’s electronic music expertise into an educational tapestry that captivates without condescension. From its visionary development amid 1990s tech constraints to its modular gameplay loops that demystify composition, the game’s strengths—intuitive visuals, authentic sounds, and thematic depth—far outweigh era-bound limitations like basic UI. It lacks narrative flash or competitive edge, yet its true genius lies in fostering unbridled creativity, turning passive listeners into active creators.

In the annals of video game history, Making Music earns its place as a foundational edutainment artifact: not a blockbuster, but a blueprint for inclusive, sensory learning that resonates in today’s app ecosystem. For parents, educators, or historians revisiting 90s software, it’s an unequivocal recommendation—timeless, transformative, and a 9/10 triumph of play-as-pedagogy. Fire up an emulator, grab a mouse, and let the painting begin.