- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Cenega Publishing, s.r.o., Hip Interactive Corp., Redback Sales Ltd., Russobit-M, Vivendi Universal Games, Inc.

- Developer: Mirage Interactive LLC

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Direct control, Shooter

- Setting: Europe, World War II

Description

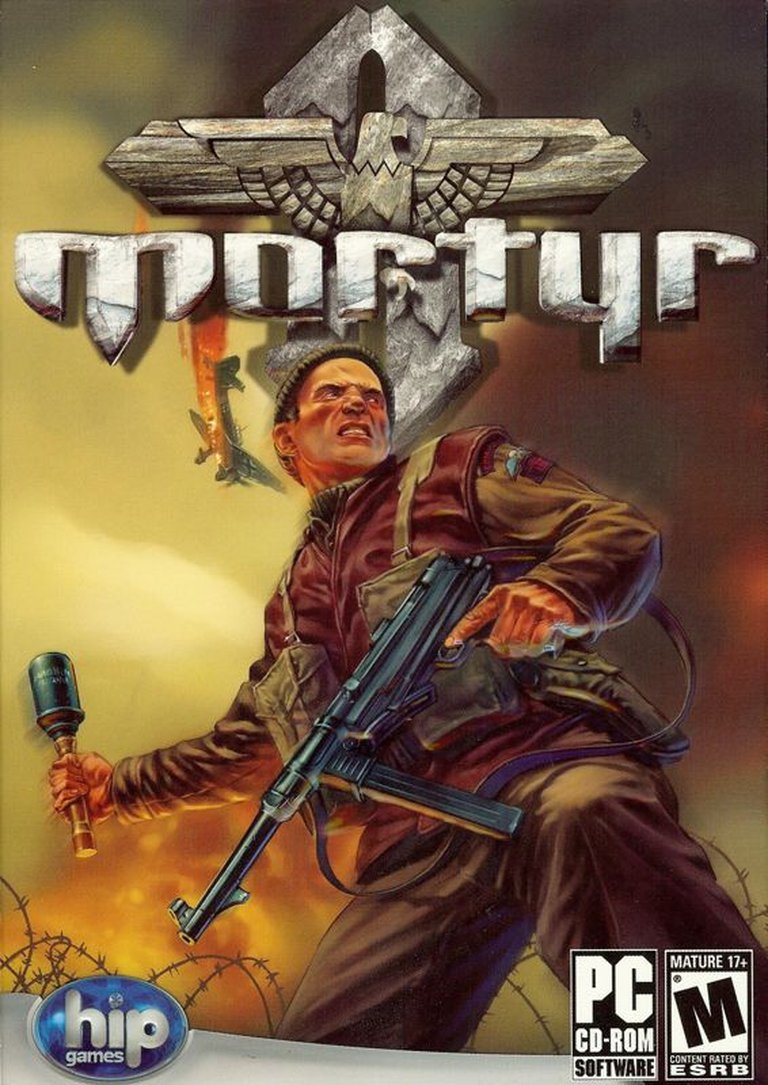

Mortyr II is a World War II first-person shooter where players take the role of Sven Mortyr, a British intelligence officer returning to his Norwegian homeland to investigate enemy operations. The plot discovers that the Nazis are developing a super-weapon using the player’s own physicist father. The game spans 11 single-player levels with a mix of historical and experimental sci-fi weapons. Additionally, 4 multiplayer levels are available. It’s known for its combination of genres and budget-friendly pricing.

Gameplay Videos

Mortyr II Cracks & Fixes

Mortyr II Patches & Updates

Mortyr II Mods

Mortyr II Guides & Walkthroughs

Mortyr II Cheats & Codes

PC

Press (‘) or (~) during the game play and enter one of the following Cheats at the console window.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| gimme mauser | Spawn Mauser |

| gimme mp40 | Spawn MP40 |

| gimme ep26 | Spawn EP26 |

| gimme mp18 | Spawn MP18 |

| gimme torba | Spawn Torba |

| gimme pzb39 | Spawn PZB39 |

| gimme panzerfaust | Spawn Panzerfaust |

| gimme fg42 | Spawn FG4 |

| invisible 0 | Turn invisibility off |

| invisible 1 | Turn invisibility on |

Mortyr II: A Case Study in Mediocrity

In the pantheon of first-person shooters, some titles are remembered for their groundbreaking innovation, others for their compelling narratives, and a select few for their catastrophic failures. Then there are games like Mortyr II, which occupy a far more obscure and fascinating space: that of the profoundly mediocre. Released in 2004 by Mirage Interactive, this sequel to the already-forgotten 1999 title arrived not with a bang, but with a whimper, landing in an industry dominated by the titanic rise of Call of Duty and the established excellence of Medal of Honor. Mortyr II is not a historically significant game, nor is it a beloved cult classic. Instead, it is a perfect, if unintentional, time capsule of the mid-2000s budget shooter—a product defined by its technical shortcomings, its derivative design, and its ultimate, almost total, irrelevance. This review will dissect Mortyr II in exhaustive detail, examining its development, narrative, gameplay, and legacy to understand precisely where and why it failed and what faint, flickering embers of potential lie buried within its flawed code.

Development History & Context

To understand Mortyr II, one must first understand the environment in which it was forged and the studio that created it. The game was developed by Mirage Interactive LLC, a Polish development house that, at the time, was something of a local industry veteran. Founded in 1997, the studio had already produced several titles, including the first Mortyr and the ill-fated Sniper: Path of Vengeance. Their ambition was clear: to create a commercially viable first-person shooter that could compete on the international stage. However, their technical and design capabilities were seemingly always a step behind the industry leaders.

The development of Mortyr II occurred during a pivotal moment for the FPS genre. 2004 was the year of Doom 3, its revolutionary use of atmospheric lighting and shadow defining a new visual standard. It was also the year Call of Duty: United Offensive and Medal of Honor: Pacific Assault refined the cinematic, scripted experience of World War II shooters to an art form. In this landscape, a small studio like Mirage was faced with an impossible technological and creative hurdle. They were attempting to build a game that looked and felt like AAA productions with a fraction of the budget, time, and talent.

The credits list a team of 34 individuals, a modest size for a project of this scope. Key personnel included Andrzej Wilewski as Team Manager and Lead Programmer, and Bartłomiej Biesiekirski as Art Director. This structure suggests a focus on internal development, but the results betray a fundamental lack of polish and optimization. The game’s description betrays its core ambition: to offer “historically accurate weapons with some experimental (or sci-fi) new ones.” This fusion was likely intended to be a unique selling point, a way to differentiate Mortyr II from the sea of authentic WWII shooters. However, without the technical prowess to realize either the historical grit or the sci-fi spectacle effectively, this hybrid concept became just another collection of assets in a bland game.

Published by a host of companies—including Vivendi Universal Games, Redback Sales Ltd., and Cenega Publishing—the game had a wide but seemingly low-budget release. It was positioned as a budget title, a fact that became both its excuse and its condemnation. Critics would later judge it against full-priced juggernauts, a mismatch that exposed its every weakness. Mirage Interactive’s vision was to create an “improbable Colossus of Rhodes-style feat of engineering,” as one reviewer put it, but the reality was a cobbled-together structure, a monument to ambition far exceeding execution.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

On paper, the narrative of Mortyr II possesses a kernel of intrigue that, with a more skilled hand, could have formed the basis for a compelling story. The player assumes the role of Sven Mortyr, a British intelligence officer of Norwegian descent. The premise is a classic spy-thriller setup: Sven is sent to his homeland, Norway, to investigate Nazi operations. The twist, however, is deeply personal: the Nazis have captured his father, a famed physicist, and are forcing him to work on a top-secret super-weapon. The plot is a direct sequel to the first Mortyr, attempting to build on the franchise’s established, albeit niche, lore.

The narrative unfolds across 11 single-player levels, taking the player from arctic fjords to heavily fortified Nazi strongholds. The mission structure is straightforward and linear, typical of the era. You are sent in to infiltrate, discover the details of the project, and ultimately rescue your father. The dialogue, as one might expect from a game of this caliber, is functional at best and cringeworthy at worst. There are no memorable characters beyond the protagonist, and the Nazis exist purely as faceless targets, devoid of any personality or motivation beyond serving as cannon fodder.

The central theme of a personal vendetta against a faceless evil is a potent one, but it is never explored with any depth. Sven’s emotional journey is told, not shown. The player is informed that this is his father, his homeland, his fight, but the game mechanics and writing fail to convey any real sense of stakes or urgency. The “super-weapon” plot device is a tired trope, used here as a simple justification for the player to shoot their way through increasingly implausible levels. The game’s title, Mortyr II: For Ever (as it was sometimes subtitled), hints at an attempt at gravitas, but the storytelling is so perfunctory that it feels like an afterthought.

Ultimately, the narrative fails because it is subservient to the gameplay. The story exists solely to string together a series of shooting galleries. There are no meaningful choices, no moral dilemmas, and no character development. It is a WWII-flavored wrapper around what is, at its core, a very basic shooter experience. The potential for a tense, personal story of espionage and familial duty is squandered in favor of a simplistic plot that serves only to push the player forward to the next firefight.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

If the narrative of Mortyr II is forgettable, its gameplay is where the game’s deep-seated flaws are most brutally exposed. At its core, Mortyr II is a straightforward first-person shooter. The player moves, jumps, and shoots, utilizing a mix of “historically accurate” and “experimental” weapons across 11 levels. The core loop is simple: enter an area, shoot all enemies, proceed to the next area. This linearity, while common in the era, is executed with such a lack of finesse that it becomes a major point of contention.

Combat and AI: The combat is the game’s most significant failing. The artificial intelligence of the enemy soldiers is, to put it mildly, abysmal. As 4Players.de noted, “what here for hirnlose KI-Feinde vom Stapel lassen werden, ist mehr als lachhaft” (what is released here as brainless AI enemies is more than laughable). Enemies exhibit little to no tactical sense, often standing idly, running into walls, or charging directly at the player’s gunfire. They fail to take cover, coordinate attacks, or present any meaningful challenge beyond requiring the player to land enough shots to terminate their lifeless forms. This makes firefights feel repetitive and unsatisfying, reducing every encounter to a mundane exercise in target practice.

Weaponry: The weapon roster is one of the few areas where the game shows a hint of ambition. Players have access to standard WWII fare like the Karabiner 98k rifle and the MP 40 submachine gun, but also “experimental” weapons. These sci-fi additions, such as an unspecified “energy weapon,” are intended to provide a unique twist. However, they are poorly integrated into the game’s balance and feel. They lack the punch and satisfying feedback of the real-world guns, and their inclusion feels more like a gimmick than a meaningful design choice. The weapon balancing is also criticized as “unfair,” with certain firearms feeling either overpowered or completely useless.

Mission Design and Level Structure: The level design is a masterclass in blandness. While some critics noted that “some Levels are really hübsch” (nice) and “the railway trips make fun,” the overall impression is one of generic, boxy environments. The levels are small and heavily segmented, requiring frequent loading screens. As Gry OnLine lamented, “fast loading is fast only in name – one should prepare for good several (dozen) seconds with the screen I am reading…” This constant pausing for loading completely destroys any sense of flow and immersion. The missions themselves are a series of tired objectives: destroy this, retrieve that, assassinate that officer. There is little variety in gameplay, and the player’s role is always the same: a one-man army.

Character Progression and UI: There is no character progression to speak of. The player does not gain experience, unlock new abilities, or improve their skills. The game is a pure test of the player’s reflexes and ability to aim, with no RPG elements to provide a sense of growth. The user interface is similarly basic and functional, showing the player’s health, ammo, and objective markers. It does its job without flair, but it is never confusing or overly complex.

The result is a gameplay experience that is technically sound in its most basic functions but creatively and mechanically bankrupt. It is a shooter that fails to provide satisfying combat, intelligent enemies, or engaging level design, leaving the player with a hollow and frustrating journey from one checkpoint to the next.

World-Building, Art & Sound

A game’s ability to transport its player to another time and place is crucial, especially for a historical fiction title like Mortyr II. In this regard, the game is a significant missed opportunity. It strives to build a world of occupied Norway and secret Nazi laboratories, but its execution is hampered by dated visuals and a poor artistic direction.

Visuals and Art Direction: Graphically, Mortyr II was dated upon release and looks even more so today. Powered by a custom engine that clearly struggled to keep up with the competition, the game’s environments are a mixed bag. Some outdoor levels, particularly those featuring snow-covered landscapes and fjords, are cited as “ansehnlich inszeniert” (well-staged) and “hübsch” (nice). The developers clearly put some effort into creating a believable Norwegian backdrop. However, these moments of beauty are few and far between. The indoor environments, such as the Nazi fortress and laboratories, are bland, repetitive, and technically lacking. Textures are low-resolution, pop-in is rampant, and the level of detail is minimal. The character and enemy models are stiff and poorly animated, further contributing to the sense of a world that is not quite real.

The German version of the game, as noted in the trivia, saw several censorship measures: all blood was removed, ragdoll effects were disabled, and all Nazi symbols were scrubbed from the game. While this was standard practice for German releases, it further sanitizes the already weak atmosphere. The absence of these iconic, if horrifying, visual elements robs the game of any sense of historical context or menace.

Sound Design: The audio is perhaps the most universally panned aspect of the Mortyr II experience. The soundtrack is described by GameSpot as a “clangorous orchestral soundtrack that won’t shut up,” implying that it is loud, intrusive, and repetitive. Sound effects are equally poor, with gunfire and explosions lacking any weight or impact. The ambient sounds that should build tension are either missing or so poorly implemented that they go unnoticed. This lack of a competent audio layer means the game fails to create any atmosphere. The arctic winds don’t howl, the echoes in the forts are nonexistent, and the tension of a stealth mission is completely absent because the player can’t hear the enemy’s approach or their own heart pounding. The audio is not just bad; it’s actively detrimental to the experience, making the world feel even more hollow and artificial.

In summary, the world-building of Mortyr II is a failure. While it has the faintest glimmers of a decent visual concept in its outdoor environments, it is utterly undone by poor execution, technical limitations, and abysmal sound design. It never succeeds in creating a believable or immersive world, leaving the player feeling as if they are merely walking through a series of uninspired, empty sets.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its release in October 2004, Mortyr II was met with a resounding thud of indifference, followed by a chorus of critical derision. The MobyGames score of 5.5 places it firmly in the bottom half of all games on the platform, and the critical average of 50% tells a story of universal mediocrity. The reviews from across Europe paint a consistent picture of a game that was, at best, an inoffensive budget distraction and, at worst, a technical mess.

The reception was defined by a constant comparison to its far superior contemporaries. Reviewers uniformly pointed to Call of Duty and Medal of Honor as the benchmarks and found Mortyr II wanting. Shooterplanet’s review is a prime example, stating, “For the full purchase price of 30,- Euro, however, one should prefer Call of Duty or Medal of Honor 2: Pacific Assault.” This sentiment echoed through nearly every major publication. The few positive notes were almost backhanded. Mygamer.com gave it a 68%, calling it “a solid budget title” that is “a good romp of a FPS, quick and dirty,” concluding that for $20, it could be “an excellent diversion.” This, however, was the absolute ceiling of praise, with most scores hovering in the 40-60% range, riddled with criticisms of poor AI, bad level design, and an overall feeling of being dated and unfinished.

The multiplayer mode, which boasted 4 levels, was almost universally dismissed as an afterthought. “Is it really necessary to talk about the multiplayer mode?” asked Jeuxvideo.com, before calling it “so poor that it is not worth wasting time on it.” The deathmatch-only offering and the complete lack of an online community cemented its status as a useless appendage.

In terms of legacy, Mortyr II is a black hole. It has had no discernible influence on subsequent games or the industry at all. It did not spawn a successful franchise, nor did it introduce any mechanics that were ever revisited or refined. It is not remembered for any particular reason, good or bad. It is simply forgotten. Its only legacy is as a case study in how not to make a shooter in the mid-2000s. For fans of Polish game development, it serves as a cautionary tale, representing the limitations of a passionate but under-resourced studio attempting to compete on a global stage. The series would limp on one more time with 2008’s Operation Thunderstorm, but by then, Mortyr II had already been consigned to the dustbin of history.

Conclusion

After a comprehensive examination of its every facet, the verdict on Mortyr II is unequivocal: it is a profoundly mediocre, deeply flawed, and ultimately forgettable video game. It is not a masterpiece of failure, nor is it a so-bad-it’s-good classic. It is simply a product that failed to meet the basic standards of its genre at the time of its release. Mirage Interactive’s ambition to create a competitive WWII shooter was noble, but their execution was crippled by technological limitations, uninspired design, and a fundamental misunderstanding of what makes a first-person shooter engaging.

The narrative, with its personal stakes and sci-fi elements, was a seed of potential that never sprouted. The gameplay, the heart of any shooter, was rendered lifeless by abysmal AI, repetitive level design, and intrusive technical issues like constant loading screens. The world-building and art direction showed fleeting moments of competence but were ultimately undone by poor optimization and sound design. Its reception was a lukewarm dismissal, and its legacy is one of complete and utter obscurity.

Mortyr II stands as a testament to the fact that passion alone is not enough to create a great game. It is a fascinating historical artifact, a snapshot of a time when the barriers to entry for AAA-quality development were insurmountable for smaller studios. For historians and journalists, it serves as a textbook example of a project that missed the mark in almost every conceivable way. For players, it is a cautionary tale to be avoided. Mortyr II is not just a bad game; it is a perfectly adequate example of a game that tried to be everything and succeeded at being nothing, securing its place not in history, but in the footnotes.