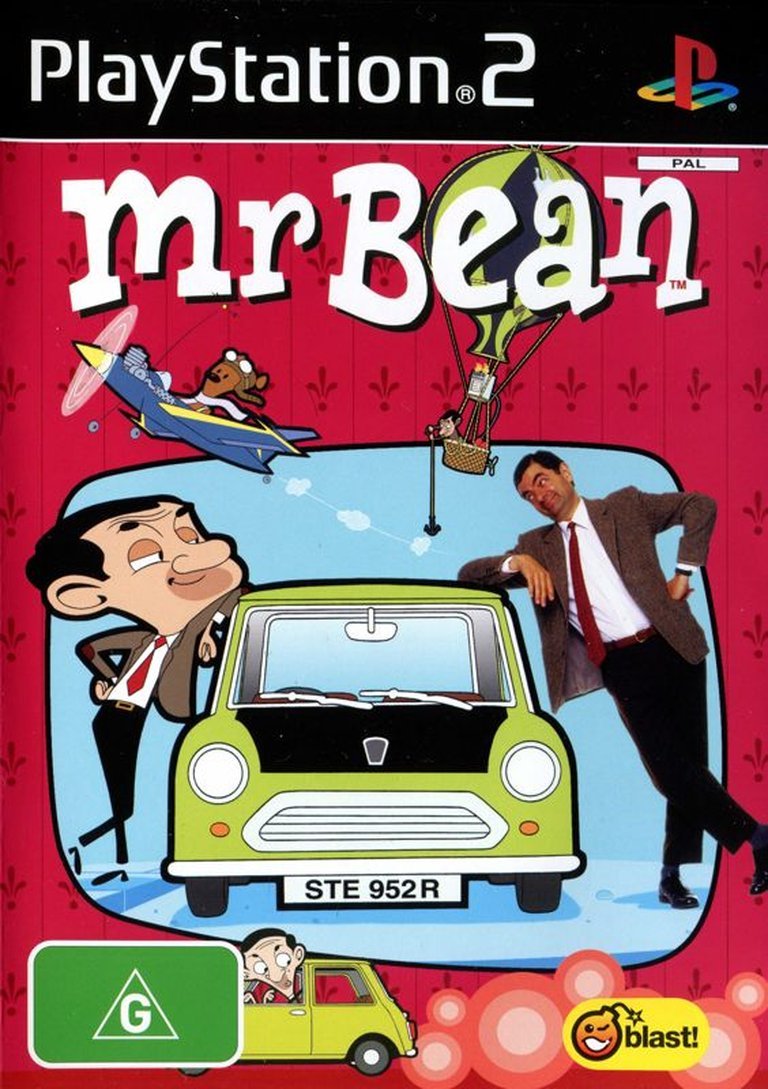

- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: PlayStation 2, Wii, Windows

- Publisher: Mastertronic Group Ltd., Red Wagon Games

- Developer: Beyond Reality Games Ltd.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Item collection, Jigsaw puzzles, Mini-games, Platforming, Puzzle-solving

- Setting: Factory, Garden, Sewers, Wilds

- Average Score: 54/100

Description

Mr Bean’s Wacky World is a third-person action-platformer game based on the animated series featuring Rowan Atkinson’s clumsy character, where players guide Mr. Bean through whimsical environments to rescue his beloved teddy bear, kidnapped by a mysterious villain demanding a ransom of 1,000 cat biscuits. The adventure spans four distinct locations—Mrs. Wicket’s back garden, murky sewers, untamed wilds, and the villain’s factory hideout—each comprising three interconnected levels accessed via a central hub, with short cartoon intros setting the scene; players battle pests and foes using tools like repellent, a frying pan, slingshot, and a temporary pirate costume for invincibility, while collecting health items, keys for treasure chests containing jigsaw pieces, and solving puzzles involving crates, bombs, and springboards to unlock exit gates through timed jigsaw challenges, supplemented by fun mini-games like whack-a-mole and tennis.

Gameplay Videos

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (50/100): Attractive graphics and faithful to the series, but monotonous gameplay that gets tiring quickly.

metacritic.com (0/100): One of the worst Wii games with bad graphics, unresponsive controls, and horrible sound design.

metacritic.com (100/100): Redefines the psychological horror genre with a thought-provoking storyline and gruesome graphics.

metacritic.com (100/100): Unique combination of art and sound, funny and bizarre, with strong replayability and recommended for everyone.

metacritic.com (100/100): Redefines the stealth-action genre with deep gameplay and polish, an important chapter in the franchise.

metacritic.com (30/100): Bad and not fun at all, with low graphics and low entertainment value.

Mr Bean’s Wacky World: Review

Introduction

Imagine a world where slapstick chaos reigns supreme, and the simple act of rescuing a beloved teddy bear spirals into an absurd quest involving cat biscuits, sewer-dwelling pests, and industrial sabotage. Welcome to Mr Bean’s Wacky World, a 2007 video game adaptation of Rowan Atkinson’s iconic animated series from 2002, where the bumbling everyman navigates peril with his trademark mix of ingenuity and incompetence. Released initially on PlayStation 2 and later ported to Wii and Windows in 2009, this third-person action-platformer promised to bottle the essence of Mr. Bean’s silent, visual comedy for a new generation of gamers. As a game historian, I’ve pored over countless licensed titles from the mid-2000s, a era when cartoon adaptations flooded the market to capitalize on family-friendly IPs. Mr Bean’s Wacky World stands as a curious artifact: a heartfelt tribute to the character’s whimsical misfortunes that, while endearing in spirit, is hampered by clunky execution and the technological limitations of its time. My thesis is clear: this game earns a niche place in gaming history as a low-budget love letter to British humor, but its repetitive mechanics and lack of polish prevent it from transcending its origins as a forgettable cash-in.

Development History & Context

The mid-2000s were a golden age for licensed video games, particularly those tied to animated TV properties, as studios sought to extend the life of popular children’s shows amid a console war between the aging PlayStation 2 and the innovative Nintendo Wii. Mr Bean’s Wacky World emerged from this landscape, developed by the UK-based Beyond Reality Games Ltd., a small studio known for budget-friendly family titles like Casper’s Scare School: Classroom Capers (2006) and Johnny Bravo in The Hukka-Mega-Mighty-Ultra-Extreme Date-O-Rama! (2005). Led by executive producer Graeme Boxall—who helmed over 70 other games, often in the casual and licensed space—the team of 47 developers (plus 8 additional credits for thanks and beta testing) aimed to capture the animated series’ cel-shaded aesthetic and physical comedy. Assistant producers Chris Gardiner and Aaron Ludlow, alongside testers like Michael Darbo and a cadre of beta volunteers (including families like the Brahmacharis and Grices, suggesting a kid-focused playtesting emphasis), worked under tight constraints typical of Mastertronic Group Ltd.’s publishing model. Mastertronic, a veteran British firm specializing in affordable, mass-market games, handled the PS2 release, while Red Wagon Games and Blast! Entertainment Ltd. oversaw later ports, reflecting the era’s trend of recycling assets across platforms to maximize ROI.

Technological limitations played a pivotal role. The PS2 version, launched on November 23, 2007, utilized CD-ROM media with a PEGI 3 rating, emphasizing single-player offline experiences on aging hardware that struggled with complex animations or expansive worlds. By 2009, the Wii port (Mr Bean’s Wacky World of Wii) leveraged motion controls via the Wii Remote for intuitive actions like shaking to escape traps or pointing to shoot, aligning with Nintendo’s family-oriented push. The Windows version, also 2009, added keyboard/mouse support and two-player minigames, but all iterations were built on modest engines—likely a variant of the Unreal Engine precursors common in low-budget titles—resulting in cel-shaded visuals that mimicked the show’s 2D animation without pushing graphical boundaries. The gaming landscape at release was saturated: competitors like Ratatouille (2007) and Shrek the Third (2007) boasted AAA production values from big publishers like THQ, overshadowing smaller efforts like this. Beyond Reality’s vision, per credits and group affiliations on MobyGames, was to create a “wacky” puzzle-platformer inspired by TV cartoons, prioritizing accessibility for young players over innovation. Yet, the era’s rush to market for holiday sales meant compromises: no voice acting beyond show clips, minimal marketing (evident in sparse promo images), and a development cycle that prioritized fidelity to the source over gameplay depth, ultimately dooming it to obscurity.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Mr Bean’s Wacky World distills the animated series’ premise into a straightforward rescue mission, but its narrative shines through subtle nods to Atkinson’s character archetype: the well-intentioned fool whose mishaps highlight everyday absurdity. The plot kicks off with Teddy—Mr. Bean’s inseparable stuffed companion—kidnapped by a shadowy villain demanding 1,000 cat biscuits as ransom. This feline-themed extortion sets a tone of whimsical menace, tying into the show’s recurring motifs of animal antics (think Scrapper the cat) and Mr. Bean’s petulant attachment to his toys. The story unfolds across four hub-connected worlds: Mrs. Wicket’s back garden (a chaotic suburban maze evoking neighborly feuds), the sewers (a grimy underbelly symbolizing hidden troubles), the wilds (untamed nature as a metaphor for Mr. Bean’s uncontrollable impulses), and the kidnappers’ factory hideout (industrial absurdity representing modern overcomplication). Each hub links three levels, prefaced by short cartoon sequences ripped or recreated from the 2002 series, providing silent, gag-filled intros that immerse players in Mr. Bean’s mute world—no dialogue, just expressive animations and sound effects.

Thematically, the game explores isolation and ingenuity, core to Mr. Bean. Without words, the player’s agency embodies Bean’s problem-solving: rummaging for keys, dodging pests, and assembling jigsaws to progress, mirroring episodes where he MacGyvers solutions from junk. Characters are sparse but iconic: Mr. Bean as the hapless protagonist, Teddy as the emotional anchor (his “health” items like medi-teddies underscore dependency), and foes like pests and baddies representing life’s petty irritants. Irma Gobb and Scrapper appear in cameos or minigames, adding relational layers—romantic tension with Irma, rivalry with the cat—without deepening the plot. The ransom quest critiques consumerism absurdly: hoarding biscuits becomes a Sisyphean task, with 1,000 needed to “win back” friendship, poking fun at transactional bonds in a kid-friendly way. Underlying themes of perseverance amid failure resonate; levels reset progress on death, forcing retries that echo Bean’s eternal optimism. Yet, the narrative falters in cohesion—no overarching villain reveal or character arcs—opting for episodic vignettes over a tight story, a flaw inherited from the show’s format but amplified by the game’s linear structure. In extreme detail, consider the factory finale: assembling a jigsaw under timed pressure while evading robotic guards symbolizes Bean’s battle against mechanized fate, but without narrative payoff, it feels rote. Overall, the story succeeds as thematic homage but lacks the emotional depth to elevate it beyond kiddie fare.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Mr Bean’s Wacky World blends third-person platforming with puzzle elements in a core loop of exploration, combat-lite encounters, and objective fulfillment, designed for bite-sized sessions suitable for young audiences. The behind-view perspective follows Mr. Bean as he traverses levels, jumping on springboards to reach high ledges, pushing crates to activate switches, or detonating bombs to clear blockades—mechanics reminiscent of early 3D platformers like Crash Bandicoot (1996) but simplified for accessibility. Combat is non-lethal and cartoonish: the repellent spray disperses swarms of pests (insects or rodents in sewers), the frying pan delivers blunt whacks to larger baddies (like aggressive wildlife in the wilds), and the slingshot snipes distant targets, such as locks or hovering enemies. The pirate costume power-up grants temporary invincibility, allowing reckless charges through hazards, which ties into Bean’s impulsive personality but is limited by short duration and rarity.

Progression hinges on a unique jigsaw system: to unlock exit gates, players collect all pieces scattered in key-locked treasure chests, then solve a timed puzzle minigame. This adds cerebral variety to the platforming, but flaws emerge—jigsaws can be fiddly on PS2 controls, and the timer induces frustration without checkpoints. Health management involves scavenging medi-teddies (Teddy-themed hearts), first-aid kits, and fruits, restoring vitality depleted by enemy contact or falls; cat biscuits serve dual purposes as currency for the ransom and collectibles for 100% completion. Character progression is minimal—no leveling or upgrades—keeping focus on skill mastery, though hubs allow backtracking for missed items, encouraging thoroughness.

The UI is straightforward but dated: a heads-up display shows health, biscuit count, and collected jigsaws, with simple menus for hub navigation. Wii controls innovate slightly, using motion gestures (e.g., swing for frying pan swings, point for slingshot), enhancing immersion but exposing input lag issues in ports. Innovative elements include environmental interactivity—sewers flood with water puzzles, wilds feature vine-swinging—but flaws abound: repetitive enemy patterns lead to boredom, platforming feels floaty due to loose collision detection, and puzzle logic occasionally stumps (why push a crate into a bomb?). Minigames provide relief: solo jigsaws, whack-a-mole (smacking pests), tennis (racket-wielding Bean), racing (cart chases), and shooting ranges (slingshot practice), with two-player modes on Wii/Windows fostering family play. Yet, these feel tacked-on, varying wildly in quality—racing is jittery, while whack-a-mole shines in chaotic fun. Overall, the systems cohere for casual play but crumble under scrutiny, revealing a game more ambitious in concept than execution.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world-building crafts a pint-sized, exaggerated London suburbia infused with Mr. Bean’s surrealism, transforming mundane settings into playgrounds of peril and puzzle. Mrs. Wicket’s garden bursts with oversized vegetables and garden gnomes as foes, evoking domestic chaos; sewers twist into labyrinthine pipes teeming with vermin, amplifying claustrophobia; the wilds sprawl with cartoonish jungles and precarious bridges, contrasting Bean’s urban awkwardness; and the factory pulses with conveyor belts and steam vents, a mechanical dystopia underscoring industrial alienation. Hubs serve as breathing rooms, with branching paths to levels and collectible teases, fostering a semi-open feel despite linearity. Atmosphere thrives on whimsy—rainbows after bomb blasts, bouncy mushrooms in wilds—contributing to an experience that’s lighthearted and exploratory, though scale feels constrained by PS2-era polygons.

Art direction embraces cel-shading, a visual technique that faithfully replicates the 2002 series’ bold outlines and vibrant flats, rendering Bean with his signature tie-flip and wide-eyed panic. Textures are basic—blocky foliage, repeated enemy sprites—but colors pop in happy primaries, appealing to kids (PEGI 3/ESRB E). Wii ports add slight polish via motion-enhanced animations, like Bean’s exaggerated waddles. Sound design leans on the show’s legacy: no dialogue, just orchestral stings, boings, and whacks from composer Neil McKenna (credited on 62 games), evoking silent comedy. Ambient noises—dripping sewers, chirping birds—build immersion, while level intros use show clips for nostalgic audio cues. Minigames amplify this with upbeat chiptunes, but flaws like repetitive loops and muffled effects (especially on Windows) detract. Collectively, these elements create a cozy, Bean-esque bubble: visually charming and sonically playful, enhancing the comedy but unable to mask technical roughness.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its 2007 PS2 launch, Mr Bean’s Wacky World flew under the radar, with no major critic reviews on Metacritic or aggregators, a hallmark of budget licensed games from Mastertronic. Player feedback trickled in slowly, averaging a dismal 1.8/5 on MobyGames (from two ratings) and a mixed 6.3/10 on Metacritic (seven Wii user reviews, blending sarcastic praise like “redefines psychological horror” with genuine gripes on monotonous gameplay). Common complaints highlighted unresponsive controls, low graphical fidelity, and uninspired levels, while positives noted its fidelity to the series and kid-friendly charm—one reviewer called it “happy colors and audible music” despite fatigue. Commercially, it underperformed: eBay listings show used Wii copies at $23–$150, signaling rarity over demand, and only 10 collectors on MobyGames. Ports in 2009 (EU/AU/US for Wii, Windows) aimed to revive interest via motion controls and multiplayer, but even these garnered sparse mentions, like VideoGameGeek’s zero ratings and four owners.

Legacy-wise, the game has faded into obscurity, emblematic of the mid-2000s licensed title glut where quantity trumped quality. It influenced few successors—developer credits link to similar flops like The Water Horse (2007)—but subtly shaped family platformers by emphasizing puzzle-platform hybrids for non-gamers. In broader industry terms, it underscores the pitfalls of IP adaptations: capturing Bean’s essence without innovation led to its niche status among retro collectors. Retrospectively, it’s a curiosity for Mr. Bean fans, preserved on sites like MobyGames (added 2013, updated 2024), but lacks the cult following of contemporaries like SpongeBob SquarePants games. Its evolution from ignored relic to ironic meme (e.g., Metacritic’s satirical reviews) highlights gaming’s oral history, influencing discussions on budget dev’s role in preservation.

Conclusion

In synthesizing Mr Bean’s Wacky World, we uncover a game that’s equal parts endearing homage and frustrating relic—a snapshot of 2000s licensed gaming where charm collides with competence. From its modest development roots and faithful narrative whimsy to creaky mechanics and cel-shaded allure, it delivers bursts of Bean-esque joy amid repetition and polish deficits. Reception confirms its marginal impact, yet as a historian, I verdict it a historical footnote: essential for understanding cartoon adaptations’ highs and lows, warranting a 4/10 for nostalgia seekers but skippable otherwise. In video game history, it reminds us that even wacky worlds need solid foundations to endure.