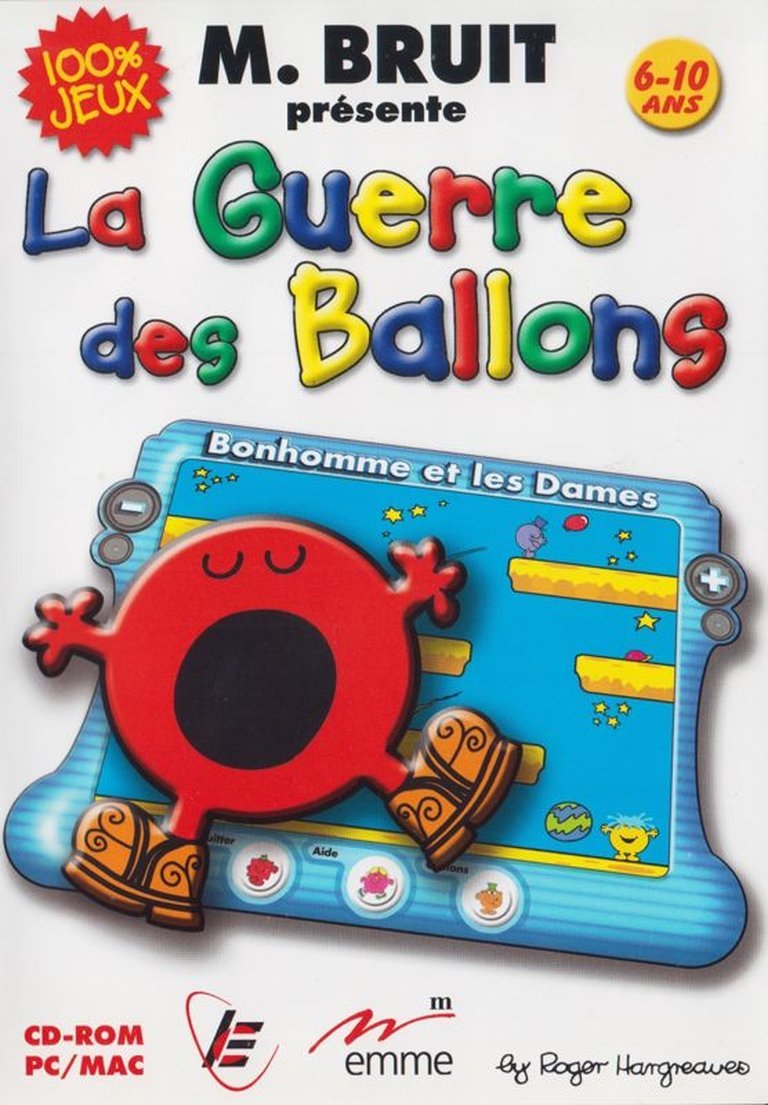

- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: EMME Interactive SA, Global Software Publishing Ltd.

- Developer: Hyptique

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Hotseat

- Gameplay: Ability usage, Arcade, Balloon capture, Obstacle avoidance

- Setting: Deep Space, Flowerpots, The Garden, The Refridgerator, The Train

Description

Based on the Mr. Men and Little Miss series, Mr. Noisy Presents Balloon War is an action arcade game where players compete across five themed stages—The Garden, Flowerpots, The Refrigerator, The Train, and Deep Space—to be the first to reach and hold balloons. Using character-specific abilities to navigate obstacles and disrupt opponents, the game features three difficulty levels and adaptive gameplay for educational purposes.

Gameplay Videos

Mr. Noisy Presents Balloon War: A Sonic Boom in Obscurity

Introduction: The Quiet After the Boom

In the sprawling, often-overlooked archives of early-2000s children’s software lies a game that embodies a very specific moment of convergence: the collision of a beloved British children’s book franchise with the ascendant, yet still nascent, world of CD-ROM casual gaming. Mr. Noisy Presents Balloon War (2001) is not a title that echoes through gaming history; it is a whisper, a forgotten piece of software that nonetheless serves as a perfect case study in the challenges of translating simple narrative concepts into interactive form for a juvenile audience. This review posits that the game is a fascinating artifact of its time—technologically constrained, philosophically aligned with “edutainment” ideals, and ultimately hamstrung by a lack of deeper mechanical ambition. It is a game that shouts its presence with its titular character’s namesake but leaves a legacy of profound silence.

Development History & Context: The Humble Workshop and the CD-ROM Boom

Studio & Vision: The game was developed by Hyptique, a studio whose history is as obscure as the game itself, and published by EMME Interactive SA (a French company) and Global Software Publishing Ltd., a publisher known for budget and compilation titles. The project was clearly a licensed product, created under the auspices of the Mr. Men and Little Miss intellectual property, created by Roger Hargreaves. The vision was almost certainly pragmatic: to create a simple, bright, character-driven arcade experience that could sit on shelves alongside other children’s software, leveraging the immediate name recognition of Mr. Men for parents making purchases.

Technological Constraints: Built for the Macintosh in 2001 and ported to Windows in 2002, the game was created using Macromedia Director 8.5. This was the standard for many CD-ROM titles of the era, especially for 2D, sprite-based games with limited animation. The technical specs reveal a project built for accessibility: compatible with Windows 95/98/ME/XP and classic Mac OS, supporting keyboard and mouse input. The “Fixed / flip-screen” perspective and “Arcade” gameplay tag suggest a static, single-screen arena per level—a design that minimized memory usage and development complexity. The CD-ROM media type was typical, allowing for basic audio and graphics but no streaming or complex assets.

The Gaming Landscape of 2001-2002: The early 2000s were a period of transition. 3D graphics were dominating the hardcore market with titles like Max Payne (2001) and Warcraft III (2002). However, the “casual” and “children’s” market remained stubbornly 2D and CD-ROM-centric. This was the era of The Learning Company’s Reader Rabbit, Humongous Entertainment’s Pajama Sam, and countless other licensed titles from Disney, Nickelodeon, and book publishers. The philosophy was often “interactive cartoon” over “game.” Balloon War entered this crowded field, not as an innovator, but as a follower, using a familiar arcade template (territory control) wrapped in a recognizable skin.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Whimsy Without Words

Unlike many licensed games that attempt to craft an original plot, Mr. Noisy Presents Balloon War operates on a level of pure, abstract premise, directly mirroring the often-simplified moral and situational structures of the original Mr. Men picture books. There is no narrative exposition, no cutscenes, no dialogue. The “story” is conveyed entirely through its title, its character selection, and its visual presentation.

The Core Premise as Narrative: The game’s description—”you must be the first to reach various balloons… once you reach the balloon, you must stay there without it being stolen”—functions as its entire plot. It is a universal, conflict-driven scenario: competition for a valuable resource. This directly channels the Mr. Men series’ tendency to use simple, high-concept social situations (Mr. Tickle’s long arms causing trouble, Mr. Messy’s chaotic nature) and boil them down to their essence. Here, “Mr. Noisy,” a character defined by his overwhelming, boisterous volume, presides over a “war.” The thematic link is tenuous but present: the loudest, most assertive presence (Mr. Noisy) might be expected to dominate this chaotic balloon battlefield, though the game’s mechanics (character-specific abilities) subvert this simple expectation.

Character as Theme: The source material states: “each character has special abilities to help them or mess up the other player.” While the specific abilities for Balloon War aren’t detailed in the provided sources, the inference from the franchise is clear. A player choosing Mr. Noisy might expect an ability related to sound—perhaps a temporary screen-shake or disruption of the opponent’s controls. Other characters from the series (Mr. Bounce, Mr. Bump, Mr. Funny, as seen in the Mr. Men Arcade Games Pack) would have abilities reflecting their core traits: bounciness, clumsiness, humor. This transforms the game from a generic balloon contest into a whimsical battle of personalities, where victory depends on understanding and exploiting a specific, child-friendly flaw or talent. This is the game’s strongest narrative thread: it’s not about soldiers or aliens, but about the chaotic interaction of distinct, archetypal personalities from Hargreaves’ world.

Thematic Underpinnings: The game subtly reinforces themes of persistence (you must “stay there” on the balloon), spatial awareness (navigating obstacles), and strategic adaptation (using your character’s unique ability at the right moment). Its most directly stated purpose is educational adaptation: “the game can also adapt to a difficult level as the player is playing, which is mainly meant for educational purposes.” This positions it not as a test of pure skill, but as a tool for developing reaction time, problem-solving, and resilience in children aged 6-10, aligning with the self-improvement ethos of the original books.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Simple Loop, A Complex Question

Core Gameplay Loop: The loop is elegantly simple and centers on territory control.

1. Reach the Goal: Navigate your character from a starting position to a designated balloon floating within the stage.

2. Claim & Hold: Upon contact, you “own” the balloon. The goal shifts from acquisition to defense.

3. Defend & Dislodge: Opponents (AI or player) will attempt to reach and touch the balloon to steal it. You must remain in contact or quickly reclaim it.

4. Score & Win: Holding the balloon for a set time or achieving a point threshold wins the round. Obstacles impede movement for all players.

The Five Thematic Arenas: The game’s world is built through its five distinct, static screen themes:

1. The Garden: Likely features flower-based obstacles, perhaps bees or sprinklers.

2. Flowerpots: Suggests a vertical or cluttered arrangement of pots to navigate around or through.

3. The Refrigerator: A classic Mr. Men setting (seen in Mr. Small and others). This implies slippery surfaces, hanging food items, and cold-themed hazards.

4. The Train: Presents moving platforms, couplings, or tunnels, introducing kinetic elements.

5. Deep Space: A thematic stretch for the series, implying zero-gravity sections, asteroids, or alien obstacles.

Each theme not only changes the visuals but, one assumes, the obstacle patterns, creating distinct “puzzle-arenas” within the simple ruleset.

Character Progression & Abilities: There is no RPG-style progression. “Progression” is purely selection-based. The player’s strategic choice lies in selecting a character whose special ability complements their playstyle or counteracts the opponent’s. The source is vague on specifics, but the design implies a rock-paper-scissors balance. For example:

* An ability that creates a temporary speed burst.

* An ability that pushes opponents back.

* An ability that creates a temporary obstacle.

This is the game’s deepest mechanical layer: a metagame of character selection and ability timing.

UI & Adaptive Difficulty: The user interface is described as minimalist and suited for children. The three difficulty levels (“Easy,” “Medium,” “Hard”) are standard. The adaptive difficulty system is its most intriguing and cited feature. “The game can also adapt to a difficult level as the player is playing.” This likely means the AI opponent’s aggression, the speed of obstacles, or the time required to hold a balloon adjusts in real-time based on the player’s success rate. This is a sophisticated feature for a children’s arcade game, explicitly designed for educational purposes—to maintain a state of “flow” for the child player, neither frustrating nor boring them. It’s a quiet acknowledgment that the game’s primary function is developmental engagement, not just entertainment.

Innovations & Flaws: The adaptive difficulty for a young audience is a genuine, if understated, innovation for its niche. However, the flaws are inherent to its design brief:

* Shallow Core Loop: The “reach and hold” mechanic, while clear, offers limited strategic depth beyond initial positioning and ability use.

* Presumed Lack of Multiplayer Depth: The description (“Play on your own or against an opponent”) suggests a two-player mode. However, given the fixed-screen, single-balloon format, it is almost certainly a simple, direct competitive mode without team play or complex rulesets.

* Repetition: With only five stages, three of which are identical in layout at each difficulty level (presumably just faster/more aggressive obstacles), longevity is minimal. It is designed for short, 10-15 minute sessions.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Static, Charming Canvas

Visual Direction: The game is a faithful, if technically unimpressive, translation of Roger Hargreaves’ iconic bold, flat, primary-color illustrations into digital form. Using Macromedia Director, the art style would have been built from digitized, simple sprites—blocky, clean, and instantly recognizable to fans. The “Fixed / flip-screen” perspective means each stage is a single, beautifully illustrated diorama, frozen in time until the characters and balloons animate across it. This creates a toy-box aesthetic, where the player is moving pieces on a living board game. The five themes provide the only real visual variety, shifting from organic garden greens to the cold blues of the refrigerator and the dark void of Deep Space.

Atmosphere & Sound Design: The atmosphere is one of calm, whimsical chaos. The sound design, almost certainly composed of low-bit MIDI tunes and standard “boing,” “pop,” and “crash” sound effects, aims for cheerful rather than immersive. There is no voice acting (a significant cost-saving measure), so characters communicate through their animations and the sound of their abilities. The absence of a complex score keeps the mood light and frantic without being stressful—perfect for its target age group. The sound of a balloon being claimed or stolen would be the central auditory feedback, a loud “POP” or triumphant fanfare, driving the core loop.

Contribution to Experience: Together, the art and sound create a cohesive, if simplistic, world. It feels less like a “game world” and more like a digital playset based on a book. This is both its strength and limitation: it captures the look and feel of Mr. Men perfectly but lacks the environmental storytelling or dynamism of more ambitious titles. It is an interactive illustration, not an interactive universe.

Reception & Legacy: The Sound of One Hand Clapping

Critical & Commercial Reception at Launch: There is a deafening silence. On MobyGames, there are zero critic reviews recorded for either the Macintosh or Windows versions. The same is true on other aggregated sites like VideoGameGeek. This is not an anomaly for obscure children’s software, but it speaks volumes. The game was not reviewed by mainstream or even niche gaming press. It was a shelf product, aimed at parents and grandparents in the toy aisle or computer store, not at gamers or reviewers. Its commercial life was almost certainly as a budget title or part of a compilation (Mr. Men Arcade Games Pack in 2002). The fact that only one player on MobyGames has it in their collection as of this writing is a stark statistic.

Evolution of Reputation: Its reputation has not evolved; it has fossilized. It is occasionally mentioned in lists of obscure Mr. Men games or as a curiosity in discussions of early-2000s edutainment. For the vast majority, it remains entirely unknown. Within the tiny community of Mr. Men fans and retro software collectors, it is remembered as a functional but forgettable mini-game collection entry.

Industry Influence: Mr. Noisy Presents Balloon War had no discernible influence on the industry. It did not pioneer a mechanic, a business model, or an aesthetic. Instead, it perfectly exemplifies a now-declining model: the licensed, CD-ROM-based, single-player or simple two-player “activity” game for young children. Its existence within the Mr. Men Arcade Games Pack places it in the lineage of compilation packs like Hasbro Family Game Night or Nickelodeon Party Blast, which repackaged simple mini-games under a single license. It represents the end of an era where a franchise could support a series of disjointed, low-budget mini-games rather than a single, cohesive “AAA” licensed experience.

Conclusion: A Curious, Quiet Footnote

Mr. Noisy Presents Balloon War is not a lost masterpiece. It is not a cult classic. It is a competent, charming, and profoundly minor artifact. Its analysis reveals the DNA of a bygone software development paradigm: a project born from a licensing deal, built with accessible tools for low-spec hardware, designed with genuine (if rudimentary) educational intent, and marketed to a non-gaming audience.

Its thesis is simple execution: take a clear, child-friendly conflict (balloon war), ground it in the recognizable traits of beloved characters, and wrap it in adaptive difficulty to ensure a positive experience. It succeeds at this modest goal. The gameplay is understandable, the visuals are faithful, and the adaptive system shows a glimmer of thoughtful design.

However, its failures are equally telling. It offers no narrative, no lasting challenge, no innovation beyond its adaptive layer, and no reason to return once the five themes are beaten. It is a snapshot of a time when “video game” and “interactive book software” were still often synonymous in the children’s aisle.

Final Verdict: In the pantheon of video game history, Mr. Noisy Presents Balloon War occupies a space smaller than a single pixel. It is a historical curiosity, a perfect specimen of early-2000s licensed edutainment. Its value lies not in what it achieved, but in what it represents: the quiet, unassuming, and ultimately ephemeral intersection of childhood literary nostalgia and the click-and-play CD-ROM economy. It is a game that makes a noise—the noise of a balloon squeaking, a character yelping, a MIDI fanfare—and then is immediately forgotten. For historians, it is a telling silence in the record. For anyone else, it is a perfectly ignorable piece of software that, in its own tiny way, did its job.