- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Global Star Software Ltd.

- Developer: 3Romans LLC

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: 1st-person / 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Car customization, Police Chase, Rally racing

- Setting: 1970s, America

- Average Score: 17/100

Description

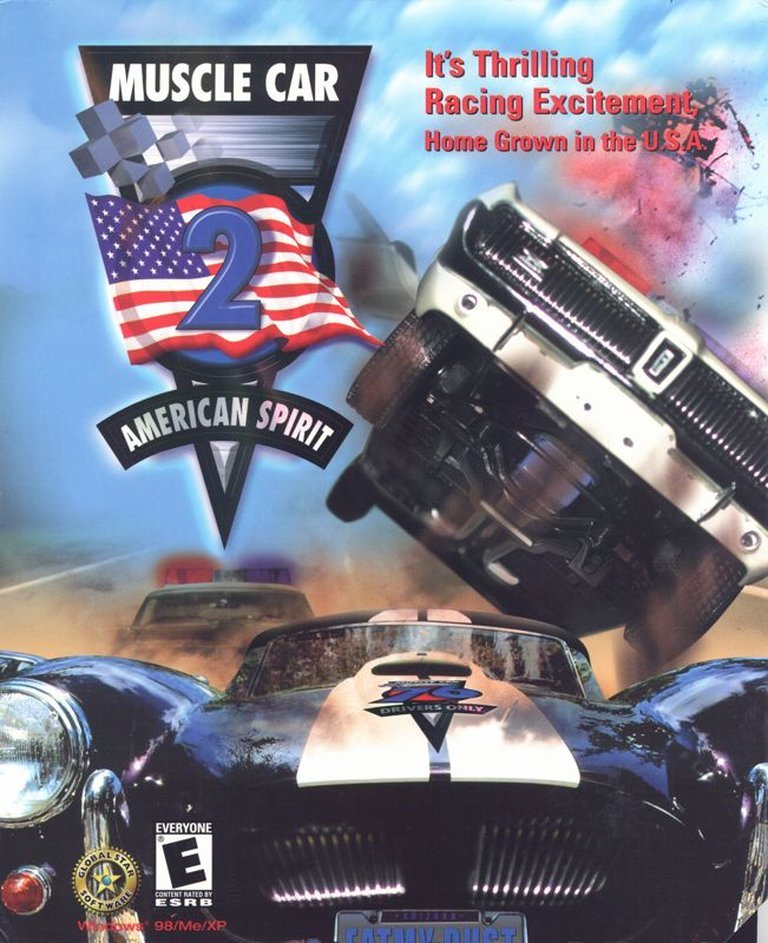

Muscle Car 2: American Spirit is a low-budget racing game featuring iconic 1970s American muscle cars, serving as a sequel to Hot Chix ‘n’ Gear Stix (also known as Muscle Car ’76). Players can enjoy rally racing, outrunning cops, and a career mode where they compete for cash to buy new cars and upgrade their vehicles with better engines, wheels, and nitrous turbo boosts, all viewed in first- or third-person perspectives.

Gameplay Videos

Muscle Car 2: American Spirit Free Download

Muscle Car 2: American Spirit Cracks & Fixes

Muscle Car 2: American Spirit Reviews & Reception

ign.com (15/100): unbearable

Muscle Car 2: American Spirit Cheats & Codes

PC

During gameplay, hold Tab and enter one of the following codes, then press Tab to activate.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| UNOCOP | Toggle Cop Car |

| UNOCASH | Get $10,000 |

| UNOSPEED | Toggle Speed Cheat |

Muscle Car 2: American Spirit: Review

Introduction

Imagine revving up a roaring ’70s muscle car, chrome gleaming under neon streetlights, ready to tear through America’s backroads in a haze of burning rubber and nitrous-fueled glory. This was the promise of Muscle Car 2: American Spirit, a 2002 PC racer that sought to capture the raw, unbridled essence of classic American iron amid the early 2000s street-racing boom sparked by titles like Need for Speed. As the sequel to the obscure Hot Chix ‘n’ Gear Stix (rebranded as Muscle Car ’76 in some releases), it arrived with patriotic flair, boasting career progression, cop chases, and rally races. Yet, beneath the stars-and-stripes veneer lies a low-budget relic plagued by unforgiving physics, dated visuals, and technical woes. My thesis: Muscle Car 2 embodies the scrappy ambition of indie-era PC gaming but crumbles under its own weight, earning a dubious place as a cautionary tale of overpromise in the muscle car genre.

Development History & Context

Developed by the tiny 3Romans LLC—a outfit led by multi-hyphenate visionary Carlo Romano, who wore hats as game designer, project director, artist, and composer—the game screamed “shoestring budget” from its CD-ROM packaging. Released in May 2002 (with some sources citing June or August variants) by publisher Global Star Software Ltd., it targeted Windows 98/ME/XP systems with modest specs: a 500 MHz CPU, 128 MB RAM, and a basic 3D-accelerated card. This was the era of PC gaming’s Wild West, where mid-tier racers like Test Drive 6 and early Need for Speed: Underground (2003) dominated, emphasizing arcade thrills, customization, and urban grit. Muscle Car 2 aped this landscape but on a fraction of the resources—no massive studio like EA Black Box, just nine credited souls including lead programmer David Rutherford and 3D artist Alan Carter.

Technological constraints were glaring: built for DirectX-era hardware, it featured rudimentary 3D models and physics engines that prioritized “feel” over realism, resulting in the “unpolished” handling noted in post-mortems like The Cutting Room Floor (TCRF). Romano’s involvement across disciplines hints at a passion project rooted in ’70s car culture, evolving from SuperChix 76 (2001), which swapped female drivers for a mixed cast in re-releases. Global Star, known for bargain-bin titles, positioned it as family-friendly (ESRB Everyone), but compatibility issues plague modern playthroughs—requiring .ini tweaks (e.g., MCE.ini “Driver=2”), dgVoodoo wrappers, or XP VMs, as lamented on abandonware forums. In a post-Midnight Club world hungry for authentic street racing, Muscle Car 2 was a plucky underdog that bit off more V8 than it could chew.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Racing games rarely boast Shakespearean plots, and Muscle Car 2: American Spirit is no exception—its “story” is a skeletal framework propping up mechanical progression rather than a cinematic epic. There’s no named protagonist or voiced dialogue; instead, the narrative unfolds through career mode as an anonymous gearhead clawing up the underground racing ladder. You start with a basic ’70s beater, grind races for cash, and ascend by purchasing flashier rides like customized Chargers or Camaros (up to 16 models, each ostensibly with unique handling traits). Progression ties into themes of American individualism and rebellion: outrunning cops symbolizes evading “the man,” while rally and bandit modes evoke bootlegger runs and speakeasy duels.

Thematically, it romanticizes ’70s muscle car lore—the oil crisis-killed era of big-block V8s, chrome bumpers, and drag-strip bravado—cloaked in “American Spirit” patriotism. Career stakes add tension: top-three finishes unlock tracks; busts incur $50 fines or “game over” after an amnesty race. Subtle motifs emerge in cop chases (law vs. freedom) and nitro-hunting shortcuts (resourceful hustling), but execution is barebones—no cutscenes, bios, or lore dumps. Dialogue? Nonexistent beyond menus. Critics like Absolute Games mocked its lack of depth, but as a historian, I see it echoing Need for Speed‘s silent protagonist archetype, distilling pure automotive machismo into a loop of earn-spend-upgrade. Flawed yet earnest, it thematizes the democratization of racing dreams for everyman players, albeit without the polish to sell the fantasy.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Muscle Car 2 loops around arcade racing with RPG-lite progression, but execution veers into frustration porn. Career mode is the “meat,” per official descriptions: 25+ street races across urban circuits demand top-three placings for cash to buy/upgrade cars (engines, wheels, nitrous). Fail too often, and bankruptcy looms—high risk amplifies tension, but punishing physics sabotage it. Cars promise differentiation (e.g., torque-heavy cruisers vs. agile ponies), yet Absolute Games nailed the truth: “all feel the same… badly.” Minor bumps trigger “unrealistic spins or flips,” sending you into ditches; AI is “incoherent,” rubber-banding erratically on unoriginal tracks.

Modes breakdown:

– Rally Racing: 8 off-road-ish city courses emphasize endurance, shortcuts, and nitro pickups.

– Bandit/Outrunning Cops: One-on-one “Underground Circuit” duels with pursuits—get tailed too long, pay fines; smash objects for bonuses.

– Time Trial: Practice with checkpoints, no progression risk.

Combat isn’t traditional but emerges in demolition-derby scraps—ramming yields crashes (unused low-quality sounds like CarCar1-3 linger in files, per TCRF). Controls toggle 1st/3rd-person views, but twitchy handling demands pixel-perfect turns. Progression shines: upgrades visibly alter stats (acceleration, top speed), fostering garage-tinkering joy. UI is clunky—basic menus, no dynamic HUD polish—but innovative for 2002 budgets: nitro management and cop heat meters add layers. Flaws abound: no multiplayer, glitchy physics (psychedelic colors on modern rigs sans fixes), and repetitive loops turn mastery into monotony. Still, masochists might grind for that one perfect run.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world is a generic American sprawl—downtown boulevards, rally trails, shadowy alleys—evoking ’70s street racing without specificity. No sprawling open-world like Midnight Club; tracks are linear circuits with hidden nitro and destructibles, fostering a gritty, lived-in atmosphere of backlot brawls. Visual direction leans low-poly 3D: blocky ’70s cars (detailed enough for era buffs), bland textures, and horizon-popping environments that scream budget constraints. Perspectives switch fluidly, but pop-in and aliasing mar immersion; modern ports reveal “psychedelic” glitches fixed via dgVoodoo.

Art contributes nostalgia—cars capture muscle car swagger (hood scoops, flares)—but landscapes are “unremarkable,” per reviews. Sound design fares worse: IGN called it “bafflingly bad,” scaring off wildlife with grating engines and crashes. Carlo Romano’s music is functional rock riffs, but unused audio (TCRF: skid-New, CarWorld1 crash booms) hints at cuts for larger collisions/UI beeps. Overall, elements coalesce into a B-movie vibe: evocative of red-white-blue rebellion, yet undermined by amateur-hour polish. Atmosphere thrives in cop chases’ tension, but repetition exposes seams.

Reception & Legacy

Launch reception was a demolition derby. Critics averaged 20%: IGN’s Ivan Sulic eviscerated it (1.5/10) as “awful… worse-sounding… waste of plastic,” likening noises to possum repellents; Absolute Games (25/100) decried “unmanageable” cars, dumb AI, and dull vistas. Players echoed at 1.5/5 (MobyGames), with zero textual reviews amplifying silence. Commercially, it flopped—bargain-bin pricing ($6-8 used today) reflects obscurity, collected by just 4-6 enthusiasts.

Legacy endures as abandonware curiosity: series spawned Muscle Car 3: Illegal Street (2003), tying to Romano’s oeuvre (Ultimate Demolition Derby). Influence? Negligible—no seismic shifts—but it prefigures budget racers like FlatOut in crash emphasis. Modern nostalgia fuels ISOs on Archive.org, XP VMs, and TCRF digs into unused assets. As historian, it’s a fossil of 2002’s indie scene: post-NFS aspirant crushed by realism’s demand, yet preserved for retro masochism. No Metacritic aggregate, but forums buzz with fixes, hinting cult potential.

Conclusion

Muscle Car 2: American Spirit roars with thematic verve—’70s muscle worship, street-hustle rebellion—but stalls on technical dead-ends: atrocious physics, ugly art, repulsive sound, and barebones execution. Its small-team grit shines in career upgrades and mode variety, but low-budget woes render it unplayable for most sans emulation hacks. In video game history, it occupies the bargain-bin underbelly: a flawed sequel bridging Hot Chix oddity to Muscle Car 3, emblematic of early-2000s PC racers that dreamed big on pocket change. Verdict: Skip unless you’re a completionist archaeologist—its spirit outpaces its machinery, a 2/10 relic best admired from afar. For true American horsepower, rev up Need for Speed: Underground instead.