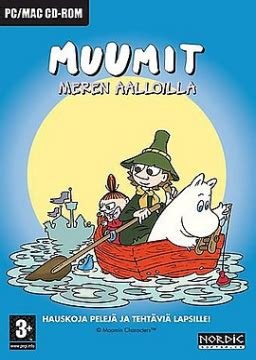

- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Nordic Softsales AB

- Developer: Bullhead AB, Norsk Strek AS

- Genre: Adventure, Puzzle

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Catching, Matching, Mini-games

- Setting: Boat, Wilderness

Description

Muumit meren aalloilla is the second installment in the Moomin video game series, where players join Moominpappa and friends on a sunny summer day aboard the Merenhuiske boat for an outback adventure. The game challenges players with various mini-games, such as catching flying fish and matching animal voices, in an adventure-puzzle format with a side-view perspective and point-and-select interface.

Gameplay Videos

Muumit meren aalloilla: A Voyage into Obscurity—A Critical Review of a Nordic Edutainment Relic

Introduction: A Calm Sea in a Vast Ocean

To speak of Muumit meren aalloilla (translated from Finnish as “Moomins on the Waves of the Sea”) is to speak of a game that exists almost entirely in the quiet, sun-dappled backwaters of video game history. Released at the dawn of the new millennium, this title represents neither a critical darling nor a commercial juggernaut. Instead, it is a deliberate, gentle, and exceptionally niche artifact—a children’s game forged from the beloved Nordic clay of Tove Jansson’s Moomins franchise. Its legacy is not one of industry-shaking innovation, but of faithful preservation, regional specificity, and the quiet, enduring power of licensed properties that prioritize atmosphere and simple joy over complexity. This review argues that Muumit meren aalloilla is a significant, if minor, cultural artifact: it serves as a perfect case study in late-1990s/early-2000s Nordic edutainment, a testament to the localized adaptations of pan-European children’s literature, and a preserved snapshot of a bygone era where a simple point-and-click interface and a collection of mini-games could suffice as a complete, marketable product. Its value lies not in revolutionary design but in its authentic, unassuming embodiment of the Moomin ethos.

Development History & Context: Sailing in Licensed Waters

The game’s development history is a microcosm of the European licensed-game ecosystem of the 1990s. Developed by Norsk Strek AS and Bullhead AB, two Scandinavian studios with a focus on children’s and educational software, and published by Nordic Softsales AB, the title was part of a prolific series of Moomin games. According to comprehensive franchise documentation on TV Tropes, this series began with Muumit piilosilla (“Moomins Playing Hide-and-Seek,” 1995) and included several sequels throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, such as Muumit ja Taikurin hattu (“Moomins and the Hobgoblin’s Hat,” 1997) and Muumit ja Taikatalvi (“Moomins and the Magical Winter,” 2000).

Muumit meren aalloilla itself presents a chronological puzzle. While the primary MobyGames listing cites a 2006 Windows release, conflicting evidence from multiple sources—including the Internet Archive’s CD-ROM image (dated 1996), Steam Games, and GOG’s Dreamlist (both citing 1996)—strongly suggests a 1996 initial release. This discrepancy is common in the archival record of small-scale, regionally distributed CD-ROM titles and highlights the challenges of preserving Nordic game history. The “2006” date may represent a re-release, a digital re-packaging, or a simple cataloging error.

Technologically, the game is a product of the CD-ROM boom. Its medium is explicitly “CD-ROM,” a format that promised rich multimedia experiences—full voice, lush graphics, and elaborate animations—that floppy disks could not. For a children’s game based on a illustrated book series, this was a perfect match. The constraints were those of the era: 256-color or limited 16-bit color palettes, pre-rendered or simple矢量 (vector) backgrounds, and basic audio sampled to fit on a single disc. The “point and select” interface and “side view” perspective were standard, low-barrier design choices for its target audience of young children and families.

The gaming landscape of 1996 was one of transition. 3D acceleration was on the horizon (Quake had just launched), but 2D point-and-click adventures and mini-game collections still dominated the children’s and “casual” markets. Titles like Pajama Sam or the Carmen Sandiego series were benchmarks. Muumit meren aalloilla entered this space not as a competitor, but as a regionally-locked alternative, leveraging the immense popularity of the Moomins—a franchise that had already seen multiple TV adaptations (from the 1969 Mūmin anime to the beloved 1990-92 Tanoshii Mūmin Ikka) and a thriving comic legacy—to carve out a dedicated Scandinavian and Northern European market.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Serenity of the Voyage

Unlike narrative-driven adventures, Muumit meren aalloilla presents a thin, anecdotal plot that serves purely as a wrapper for its activities. As described by MobyGames and Kotaku, “The Moomins and their friends have decided to set off on a hot summer’s day on Moominpappa’s Merenhuiske boat for the outback.” This premise is lifted directly from the cozy, adventurous spirit of Tove Jansson’s original books, particularly Moominpappa at Sea (1965), where the family’s nautical wanderings are central.

The narrative is not told through dialogue trees or cutscenes but is environmentally implied. The player is a participant in this summer day out, not a protagonist with a name or agency. The goal is simply to “accept challenges in various mini-games.” This approach is deeply faithful to the source material’s themes. The Moomins are not heroes on a quest; they are a found family experiencing the small wonders and minor inconveniences of existence. The game’s thematic core is therefore one of contemplative play, gentle problem-solving, and communal harmony.

The characters—Moomintroll, Snufkin, Little My, Moominmamma, Moominpappa, Snork Maiden—are not developed but are presented as familiar icons. Their presence is enough. The game’s “story” is the journey itself: the rocking of the boat, the endless sea, the discovery of a flying fish or a strange sound. This reinforces the Moomin philosophy that adventure is not about conflict but perception, and that companionship turns mundane moments into memories. The lack of a villain, a clear objective, or a climax is not a design flaw but an aesthetic and philosophical choice, aligning with the books’ rejection of traditional dramatic tension in favor of melancholic, whimsical digressions.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Mini-Game archipelago

The core gameplay loop is a hub-and-spoke mini-game collection. The player, from the deck of the Merenhuiske, selects different “challenges” or activities, each representing a small vignette of Moomin life at sea. The two explicitly named mechanics from the source material are telling:

- “Catching flying fishes”: This implies a timing-based action game, likely using the mouse to click or drag as fish leap from the water. It tests reflexes but in a forgiving, rhythmic way.

- “Matching the correct voices to animals”: This is an auditory memory and association puzzle. Players likely hear various animal sounds (a grunt, a chirp, a splash) and must match them to illustrated characters (perhaps Snufkin, a hedgehog, a Fillyjonk). It’s a simple but effective exercise in sensory recognition, fitting for young children.

These examples reveal the game’s entire design philosophy: accessible, skill-based mini-games with a strong thematic skin. The interface is “point and select,” requiring only a mouse click to navigate from the boat hub to a mini-game and back. There is no inventory, no character progression stats, no failure state with consequences (likely a “try again” or a gentle reset). The “gameplay” is the act of engagement itself.

The systems are intentionally non-invasive. There is no score attack, no timer creating stress (beyond the inherent timing of a “catching” game), and no narrative branching. The player’s “progress” is simply the completion of a set of activities. This design was common in Nordic edutainment of the period, where the goal was engagement and gentle cognitive stimulation, not mastery or competition. The “inventive or flawed systems” are the entire package: its flaw is a lack of depth for older players; its innovation is in its pure, unadulterated focus on a specific age group and tone. It is a game that does not pretend to be anything other than a series of playful tasks set in a beloved world.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of Moominvalley at Sea

Without access to the game’s assets (no screenshots are available in the provided sources, and the item on the Internet Archive has no previewable files), we must reconstruct its aesthetic from the franchise’s established visual and auditory language and the technological norms of 1996 CD-ROM children’s games.

Visual Direction: The 1990 anime Tanoshii Mūmin Ikka had set a modern, clean, and vibrant standard for Moomin animation. The game almost certainly would have used digitized stills or simple sprite-based animations derived from this anime style or the original book illustrations (which are more sketch-like and watercolor). The color palette would be soft, pastel, and warm—lots of blues for the sea and sky, greens for the boat, the distinctive off-white/pink of the Moomins themselves. The “side view” perspective suggests a cross-section of the boat and sea, with characters as static or lightly animated sprites against a scrolling or static background. The art would be literal and illustrative, prioritizing clarity and recognition over artistic flair, ensuring a child could instantly identify Snufkin’s green hat or Little My’s red dress.

Sound Design: For a CD-ROM title, full voice acting would have been a stretch for a small Nordic studio, but ambient sea sounds (waves, seagulls), simple cheerful music (likely MIDI-based, with a folk-inspired, open-air melody), and character-specific sound effects (Moomintroll’s soft grunt, Little My’s sharp giggle) would be present. The “voice matching” mini-game confirms that recorded animal and character sounds are a key feature. The soundscape would be designed to be calming and immersive, reinforcing the lazy summer day premise rather than exciting the player.

Atmosphere & Contribution: The world-building is diegetic and seamless. There is no separation between “menu” and “game”; selecting a mini-game is framed as deciding what to do next on the boat. This creates a cohesive, toy-box-like atmosphere. The art and sound work together to sell the fantasy of being on that boat with the Moomins. It’s not a vast, explorable Moominvalley but a microcosm—a single vessel on a vast, peaceful sea. This focus on a constrained, intimate space is perfectly in line with the cozy (or mysig) aesthetic central to Nordic children’s culture and the Moomin books’ focus on the home as a sanctuary.

Reception & Legacy: The Quietly Preserved

Given its completely absent critical and player review record on MobyGames—”Be the first to add a critic review” and “Be the first to review this game!”—Muumit meren aalloilla was, upon its release, a commercially modest and critically ignored title outside its core Scandinavian/Nordic market. Its audience was families with young children familiar with the local-language TV broadcasts and book editions. It succeeded within that narrow lane as a competent, charming piece of merchandise.

Its reputation has evolved into one of preservation and niche reverence. Its inclusion on the Internet Archive (as a 277.5MB CD-ROM image) and its listing on the fan-run MuumiPeli site—dedicated to archiving “legendary games you can’t really get anymore”—are its primary contemporary hallmarks. It is not a “lost” game in the dramatic sense (like Muumipappa kalassa), but a forgotten one, relegated to digital attics by the expiration of its license and the march of gaming technology. The GOG Dreamlist receiving 42 votes indicates a persistent, if tiny, community interest, likely driven by nostalgia and a desire for official preservation.

Its influence on the industry is negligible. It did not pioneer a mechanic or inspire a genre. However, within the micro-history of the Moomin game franchise, it is a pivotal middle entry. It follows the hide-and-seek formula of the first game and precedes more narrative-driven titles like Muumit ja Taikaturmio (The Moomins and the Hobgoblin’s Hat) and Muumit ja salaperäiset huudot (The Moomins and the Mysterious Screams). It represents the series’ commitment to a consistent, low-stakes gameplay model for children, a model that would eventually give way to more adventure-oriented designs, as seen in the 2024 stealth game Snufkin: Melody of Moominvalley.

Conclusion: A Gentle Anchor in a Turbulent Sea

Muumit meren aalloilla is not a game to be judged by conventional metrics of innovation, narrative complexity, or graphical prowess. To do so would be to fundamentally misunderstand its purpose. It is a cultural vessel, carrying the comforting, sunlit atmosphere of the Moomin books into the interactive realm of the 1990s family PC. Its development by small Nordic studios under a tight license, its use of the CD-ROM format to deliver simple sensory experiences, and its complete embrace of a non-competitive, exploratory mini-game structure mark it as a perfectly preserved artifact of its time and place.

Its historical significance lies in its representative sameness. It is one of many such licensed children’s games—the European counterpart to American titles like The Bernstein Bears or Arthur’s computer games. Yet, in its specific cultural context, it is a primary source document for understanding how a quintessentially Nordic, philosophically gentle property was adapted for early interactive media. It prioritizes mood over mechanics, familiarity over challenge, and comfort over conflict.

For the game historian, it is a valuable data point. For the Moomin fan, it is a charming, ephemeral bridge to the world of the books. And for the preservationist, it is a title that must be safeguarded—not because it is great, but because it is authentic. In the end, Muumit meren aalloilla succeeds on its own humble terms: it lets you spend a quiet, sunny afternoon on a boat with old friends, sailing nowhere in particular, and that is a voyage worth preserving.