- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Micronet S.A.

- Developer: Freedom Factory Studios

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Puzzle elements

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

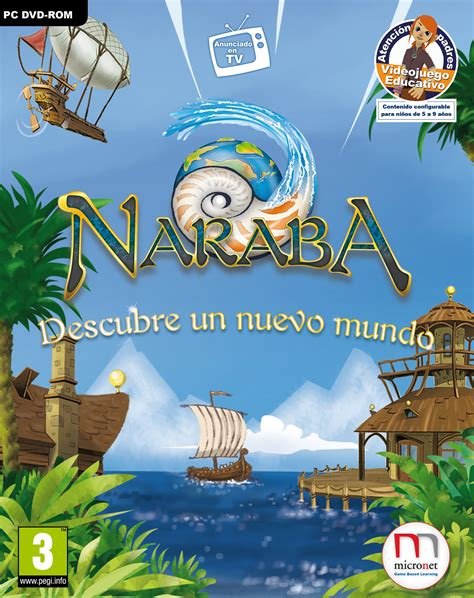

Naraba: Discover a New World is an educational PC game for children aged 5-9, set in a vibrant fantasy universe. As the core title of the ‘World of Naraba’ series, it combines exploration and playful learning with over 60 mini-games and 100 missions tied to school subjects like math, logic, and foreign languages. The game features a multilingual interface (Spanish, English, German, French) to help kids acquire vocabulary while solving puzzles, and aligns with EU educational standards for early childhood development.

Naraba: Discover a New World: Review

Introduction

In the crowded landscape of edutainment titles, Naraba: Discover a New World (2010) dared to reimagine how young learners interact with academic concepts. Developed by Barcelona-based Freedom Factory Studios and published by Micronet S.A., this PC-exclusive title aimed to fuse fantasy-adventure aesthetics with rigorously structured educational content. But did it transcend the genre’s limitations, or vanish into obscurity? This review unpacks the ambitious design, technical triumphs, and sobering limitations of an underdocumented artifact in children’s gaming history.

Development History & Context

Studio Vision & Educational Mandate

Freedom Factory Studios—a then-nascent Spanish developer—partnered with educational consultants and teachers to align Naraba with the EU’s Competencies for Lifelong Learning framework. Targeting 5–9-year-olds, the project sought to “imperceptibly” integrate curriculum fundamentals (math, logic, foreign languages, art, and music) into a cohesive fantasy world. This was no mere minigame compilation; Naraba intended to be the narrative hub for a broader franchise, evidenced by companion titles like Naraba World: El Palacio Misterioso (2010).

Technological Constraints & Ambitions

Built on the CyberBase Engine, the game featured 3rd-person exploration across pre-rendered 2D environments with Flash-animated elements (per AbandonWiki). System requirements—Windows XP, DirectX 9.0c, and a Core 2 Duo CPU—were modest even for 2010, prioritizing accessibility over graphical fidelity. However, the engine’s limitations later haunted preservation efforts: modern GPUs (especially Nvidia) triggered crashes, necessitating fan-made fixes like dgVoodoo 2 wrappers to bypass defunct DRM activation servers (MyAbandonware).

Industry Landscape

Released in Spain in December 2010 (with a 2012 French rollout, per Metacritic), Naraba entered a market dominated by Nintendo’s Big Brain Academy (2005) and Art Academy (2009). Unlike competitors, it emphasized language acquisition via a built-in multilingual toggle (Spanish, English, German, French)—a progressive feature for its demographic.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The World of Light and Shadow

Naraba framed its educational tasks within a high-stakes fantasy allegory: players guided two protagonists—Tempo, a light-attuned scholar, and Serra, a shadow-aligned warrior—through a realm fractured by imbalance. Through 100+ quests, they restored harmony by solving puzzles tied to real-world subjects. Dialogue and environmental storytelling (e.g., math-based bridge repairs, music-activated portals) reinforced themes of collaboration, cultural curiosity, and intellectual courage.

Secret Education: Mechanics as Metaphor

Each activity doubled as thematic reinforcement:

– Language Puzzles: Acquiring vocabulary unlocked lore tablets, mirroring real-world literacy empowerment.

– Math Challenges: Calculating resource allocations for in-world townspeople framed arithmetic as communal caretaking.

The narrative avoided didacticism by embedding pedagogy into world-building—a subtlety atypical for the genre.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop & Progression

Players explored interconnected zones (e.g., crystalline forests, luminescent caves), triggering context-sensitive minigames (60+ total). Success granted “Wisdom Fragments”, gatekeeping later areas—a Metroidvania-lite structure rare in edutainment. Progression felt tangible: learning to count in French might unveil a treasure vault, validating skills narratively.

Educational Mechanics Breakdown

| Discipline | Example Activity | Innovation Flaws |

|---|---|---|

| Math/Logic | Pattern-recognition tile puzzles | Over-reliance on abstract symbols |

| Language | Vocabulary matching via creature dialogues | No phonetics training |

| Art/Music | Rhythm minigames, color-mixing challenges | Limited creative agency |

While diverse, activities lacked adaptive difficulty—a missed opportunity to personalize learning.

UI/UX & Accessibility

The radial menu and icon-driven HUD optimized for young players. However, keyboard/mouse controls felt clunky compared to console-centric contemporaries. Worse, technical instability (texture glitches, save corruption) undermined its child-friendly ethos.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Aesthetic Philosophy

Naraba blended whimsical Euro-fantasy (reminiscent of The Legend of Spyro) with pedagogical clarity. Pre-rendered backdrops—lush canals, aurora-lit ruins—evoked storybook illustrations, while character designs leaned into archetypes (e.g., owl sages, crystalline golems) for instant readability.

Ambience as Teacher

Sound design catalyzed immersion:

– Diegetic music: Notes from environmental instruments (e.g., glowing harp flowers) taught pitch recognition.

– Multilingual VO: Characters seamlessly switched languages during replayable dialogues, incentivizing experimentation.

Yet, limited animation variety (especially NPCs) betrayed budget constraints.

Reception & Legacy

Commercial Obscurity & Critical Silence

No critic reviews survive on Metacritic or MobyGames, signaling minimal press outreach. Player reviews are equally absent—evidence of distribution failures, possibly tied to Micronet’s regional focus. The franchise’s sole lasting imprint came via abandonware portals, where preservationists archived its DRM-locked files.

Industry Ripples

Indirectly, Naraba presaged later successes:

– Immortals Fenyx Rising (2020): Adopted similar mythoscience puzzles but for mainstream audiences.

– Languages/Travel Tutors (e.g.,* Duolingo): Echoed its contextual vocabulary drills.

Sadly, its **integration-first pedagogy remains underutilized in AAA family titles.

Conclusion

Naraba: Discover a New World was honorable ambition hampered by execution. Its fusion of narrative depth and curricular rigor surpassed genre peers, while instability and poor marketing doomed its reach. Today, it stands not as a masterpiece, but as a proof-of-concept—one that dared to treat children as explorers, not just students. For historians, it’s a flawed yet fascinating relic of Euro-educational idealism; for players, a charming time capsule best enjoyed via community-patched abandonware. 6/10—A shadowed titan awaiting rediscovery.