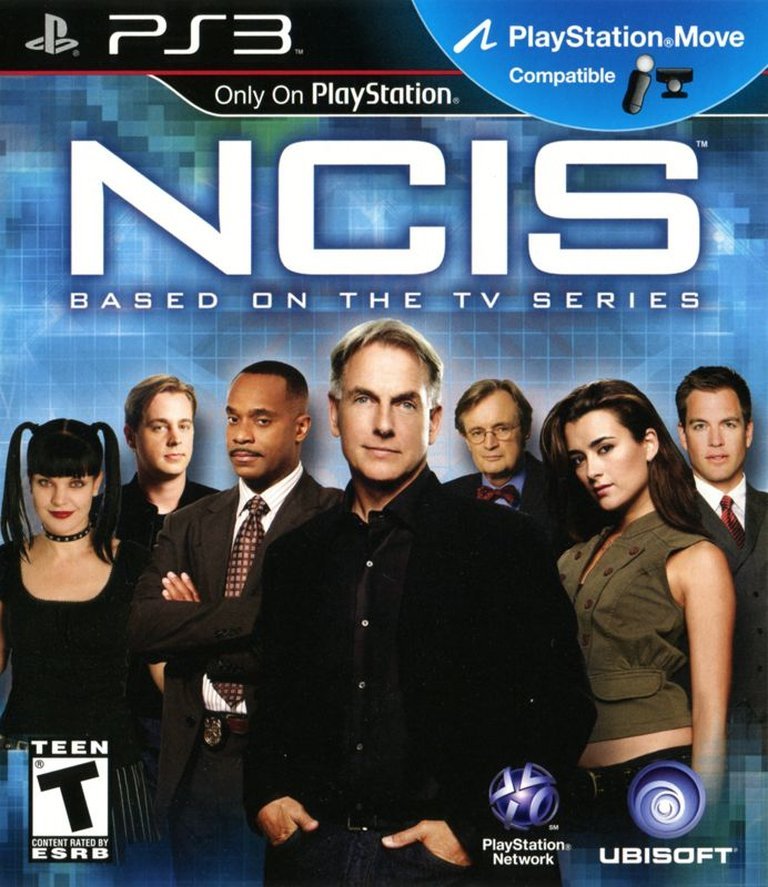

- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: PlayStation 3, Wii, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Ubisoft Entertainment SA

- Developer: Shanghai UBIsoft Computer Software Co., Ltd.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Detective, Mystery

- Average Score: 35/100

Description

NCIS is a third-person adventure game based on the popular TV series, where players control key members of the NCIS team—such as Gibbs, DiNozzo, Abby, and McGee—to investigate crime scenes, perform forensic analyses, and solve puzzles across four episodic storylines. The narrative begins with a seemingly straightforward bank robbery that unravels into a complex terrorist conspiracy with a nuclear threat, faithfully capturing the show’s humor, detective mystery, and collaborative investigative style.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy NCIS

PC

NCIS Cracks & Fixes

NCIS Guides & Walkthroughs

NCIS Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (35/100): I can only recommend this game to anyone who bleeds NCIS love from their veins or lives on trophies; for everyone else it’s just not worth the time.

metacritic.com (35/100): This is the kind of game you can easily give to an elder family member if they are a fan of the show, without ever having to explain how it works.

NCIS (2011): A Case File in Licensed Game Mediocrity

Introduction: The Franchise, The Fallacy, The Forensic Failure

In the early 2010s, the video game industry entered a period of frenetic, often cynical, franchise exploitation. Every successful television show—from procedural dramas to sci-fi epics—seemed destined for a cheap, low-effort interactive adaptation. These games were frequently developed on tight budgets and tighter deadlines, targeting a captive audience of fans rather than the broader gaming public. Few titles exemplify this trend with such stark, unflinching clarity as Ubisoft Shanghai’s NCIS, released in 2011. Ostensibly an adventure game letting players step into the shoes of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service’s elite team, the final product is a masterclass in missed opportunity, a game that understands the surface of its source material but fundamentally misunderstands what makes it—or any game—engaging. This review will dissect NCIS not merely as a bad game, but as a critical artifact of a specific, disreputable era in licensed gaming, arguing that its legacy is defined by its profound failure to translate compelling television narrative into compelling interactive experience, resulting in a shallow, repetitive, and ultimately insulting cash grab that tarnished the brand it sought to celebrate.

Development History & Context: Ubisoft’s Assembly Line

NCIS was developed by Ubisoft Shanghai, a studio with a history of producing licensed titles and sports games rather than original, acclaimed work. This was not a team of auteurs given creative freedom; it was an assembly line tasked with efficiently transforming a hot television property into a marketable product. The development timeline appears short—announced in September 2011 and released globally by November—suggesting a production cycle measured in months, not years. This places the game in the direct shadow of Ubisoft’s own CSI series of forensic adventure games, which used a similar template of mini-game-driven investigations.

The technological constraints of the era were not an excuse. The game released on PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, and PC—systems capable of far more sophisticated storytelling and gameplay, as demonstrated by narrative-heavy titles like Heavy Rain (2010) and L.A. Noire (2011). Instead, NCIS uses a dated, simplistic third-person “point-and-click” framework with low-polygon character models and bland, repetitive environments. The 2011 gaming landscape was one where players increasingly expected licensed games to offer authentic experiences, not just skin-deep familiarity. NCIS arrived at the tail end of this trend’s most egregious phase, just as the industry was beginning to pivot toward higher-quality adaptations (e.g., The Walking Dead by Telltale later that year). Its context is one of calculated minimalism, designed for the lowest common denominator and the quickest profit.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Plot Without Pulse

The game’s narrative structure attempts to mirror the television series’ “case-of-the-week” format while building a season-long arc. It presents four self-contained episodes that, per the official description, start with “a murder in a casino” and escalate into “a dangerous terrorist conspiracy and a nuclear threat,” spanning locations like Atlantic City, Iraq, and Dubai.

The Illusion of Scope: In practice, the “episodes” are glorified case files. The terrorist conspiracy is paper-thin, a MacGuffin to connect four otherwise unrelated crime scenes. There is no real serialized storytelling; the finale merely ties the four villains together under a single, nebulous organization. Compare this to the show’s own escalating, character-driven arcs (like Ziva’s captivity storyline) or even the dense, intersecting plots of contemporary games like Heavy Rain. NCIS offers plot as a skeleton, lacking the dramatic weight, moral ambiguity, or genuine stakes that define the series at its best.

Character: Impersonation Over Embodiment: This is the game’s most tragic failure. The script, credited to Jess Lebow, aims for the show’s signature blend of procedural jargon, gallows humor, and team camaraderie. It sounds like NCIS, but it never feels like it. The primary reason is a devastating voice-acting crisis. Only two actors from the series reprise their roles: the legendary David McCallum as Dr. Donald “Ducky” Mallard and Robert Wagner as Anthony DiNozzo Sr. The rest are sound-alikes, with varying degrees of success. Josh Robert Thompson as Gibbs captures the gravelly tone but none of the gravitas or subtlety; the performance is a caricature of a “gruff leader.” The disconnect between these voices and the often-stiff, unconvincing 3D character models (DiNozzo is frequently cited as looking “zombiesque”) creates an uncanny valley of narrative failure. The players are not interacting with the NCIS team; they are puppeteering inferior impersonators in a play with a sub-par script.

Thematic Emptiness: The show is, at its core, about found family, the weight of duty, and finding humor in darkness. The game nods to this with cutscenes attempting banter, but the interactions are rote and lack the chemistry that took the series years to build. The “humor” often falls flat, feeling like a checklist ofTony-isms and Abby-isms. The thematic exploration of military culture, sacrifice, or justice is completely absent. The game is a procedural without the procedure’s soul.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Repetition Loop

The gameplay is a cycle so rigid it could be programmed by flowchart: Crime Scene → Evidence Collection → Lab Mini-Games → Deduction Board → Interrogation. This structure is not inherently flawed, but NCIS executes each step with such breathtaking simplicity that it negates any sense of investigation or discovery.

-

Character-Specific Actions (The Gimmick): The core conceit is controlling different team members. Field agents (DiNozzo, Ziva) handle scene investigation: taking photos, moving objects, finding hidden items. Abby handles forensics: matching bullets, analyzing chemicals, comparing fingerprints. McGee “hacks” (a mini-game of clicking symbols). Ducky performs autopsies on 3D holograms, clicking on points of interest. Gibbs interrogates once enough evidence is gathered. The problem is that these are not unique gameplay experiences; they are reskinned versions of the same basic mechanic: “find the interactive热点 and click/press a button.” Switching characters is less about strategic problem-solving and more about fulfilling a quota of tasks for each persona.

-

The Mini-Game Menagerie (The Monotony): The forensic mini-games are lifted directly from the CSI formula and are insultingly easy. They involve:

- Match the Pattern: Matching fingerprints, bullet striations, or chemical compositions. These are simple “spot the difference” or drag-and-drop exercises with zero failure state.

- Sequence/Password Guessing: McGee’s hacking is a timed sequence of clicking icons or entering simple passwords (often found on documents nearby).

- Satellite Tracking: A mini-game where you guide a circle over a map to follow a car, with no real challenge.

These “puzzles” offer no intellectual resistance. They are interactive loading screens. The difficulty never scales, making the entire 4-5 hour experience a passive, momentum-sapping trudge.

-

The Deduction Board (The Farce): Gibbs’s “deduction board” is presented as the game’s climactic moment of insight. In reality, it’s a literal drag-and-drop exercise where the game highlights the exact two pieces of evidence to connect, with no possibility for incorrect association. It is the antithesis of detective work, which is about forming theories from disparate clues. Here, the game forms the theory for you.

-

UI & Controls: The third-person camera is often unhelpful, and the pointer-based control scheme is clunky, especially on consoles. The “objectives” menu removes all exploration and discovery, telling you exactly what to do next. There is no inventory management, no dialogue choices, no consequence, and no branching paths. The game is on rails, and the rails are made of soggy cardboard.

Innovation? None. The only “innovation” is the cynical packaging of these tired mini-games within a popular franchise, attempting to disguise their simplicity with familiar character skins.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Facade Cracking at the Seams

The game’s presentation is a study in inconsistent quality that mirrors its design philosophy: some elements receive just enough attention to be recognizable, while others are visibly neglected.

-

Visual Direction & Character Models: The environments (casino, military base, hotel suites) are drab, low-texture, and spatially cramped. They serve as functional backdrops for pixel-hunting but lack any atmosphere or detail. The character models are the most glaring issue. As noted, Ziva and Abby are perhaps passable, but Gibbs and DiNozzo are poorly proportioned and animated. The “zombiesque” description is apt—mouth movements are robotic or absent during speech, and movements are stiff. The cutscenes use a mix of static character portraits with a moving camera (a cheap technique) and fully animated sequences, creating a jarring, disjointed visual narrative. This inconsistency screams of budget re-allocation: certain scenes or characters got a few extra polygons, while others were left to languish.

-

Sound Design & Music: The game’s one unqualified success is its audio. It features the iconic NCIS theme music and several sound effects from the show (the “thump” of a crime scene photo, the computer chirps). This immediately establishes a sense of familiarity. However, this is undercut by the aforementioned voice-acting disparities. McCallum’s and Wagner’s performances are professional and authentic, creating a bizarre cognitive dissonance when contrasted with their sound-alike colleagues. The soundtrack is recycled but effective.

-

Atmosphere: The game fails utterly to build the tense, atmospheric mood of the show. The procedurally generated “crime scene” music is generic and moody, but the repetitive gameplay and ugly environments drain any potential suspense. The serious themes of murder and terrorism are rendered cartoonish by the simplistic interaction.

Reception & Legacy: A Critical Panning and a Cautionary Tale

NCIS was not just poorly received; it was derided. Its Metacritic scores are damning: 35/100 on Xbox 360 (Generally Unfavorable) and 50/100 on PlayStation 3 (Mixed). The critical consensus was brutally unified.

- The Critic Onslaught: Reviews are a litany of contempt. GameSpot’s “Childish minigames and saw-it-coming plots make NCIS a mockery of its TV inspiration” (2/10) is a typical summary. Official Xbox Magazine called it “rote button-pushing that feel less like a game experience and more like channel-surfing on your couch” (3/10). IGN offered the most prescient verdict: “I can only recommend this game to anyone who bleeds NCIS love from their veins or lives on trophies; for everyone else it’s just not worth the time.” This perfectly encapsulates the game’s inevitable audience: completionist fans or the curious, all of whom would be disappointed.

- The Fan Backlash: User reviews, while slightly more forgiving on aggregate (owing to fan bias), are rife with disappointment. Common complaints: missing original voice actors (only 2 of 6+ main characters), graphics that don’t capture the actors’ likenesses, and an insultingly short playtime (4-5 hours for $40). One user review on MobyGames perfectly summarizes the feeling: “I love NCIS. I am a huge fan of the show, but I was disapointed [sic] with the game.”

- Legacy as a Warning: NCIS has no positive legacy in terms of influence. Its legacy is purely cautionary. It stands as a peak example of the “fast-food” licensed game: mass-produced, nutritionally void, and quickly forgotten. It demonstrated that even with a #1 rated television show as a license, a developer could produce a game so devoid of passion or quality that it would be remembered only for its failures. It poisoned the well for future TV adaptations, making publishers and fans more wary. Its existence likely contributed to the industry’s gradual shift away from this model toward either smaller, narrative-focused digital adaptations (like Telltale’s model) or avoiding licensed games altogether unless a major studio with a proven track record (like Rockstar with The Warriors) was involved. It is a footnote in gaming history, but an essential one: the textbook case of how to fail a franchise translation.

Conclusion: The Final Verdict on a Failed Investigation

NCIS (2011) is not merely a bad game; it is a profound betrayal of potential. It had a beloved, character-rich franchise with a built-in audience. It had a studio with the resources to create a compelling detective-adventure. It had a market hungry for interactive narratives. What it lacked was any respect for the medium of games or the intelligence of its audience.

The game is a hollow ritual. It simulates the actions of an NCIS agent—taking photos, running scans, interrogating—but none of the craft. There is no deduction, no intuition, no consequence. It is a toy detective kit for toddlers, priced for adults. Its technical shortcomings are forgivable; its foundational laziness is not. The mini-games are trivial, the story is a B-plot stretched thin, the character impersonation is embarrassing, and the entire experience is a repetitive, soulless grind masquerading as interactivity.

Historically, NCIS belongs in the museum of licensed game horrors. It represents the nadir of the “TV show to video game” pipeline, a product so calculated and cash-focused that it actively harms the brand it licenses. It is a testament to the idea that a strong intellectual property cannot save a poorly conceived game. For scholars, it is a perfect case study in development commodification. For players, it is a five-hour warning: not all franchises deserve the interactive treatment, and when they receive it without care, the result is not just bad gaming—it’s an insult to the source material and a waste of everyone’s time. The verdict is final: case closed, with prejudice.