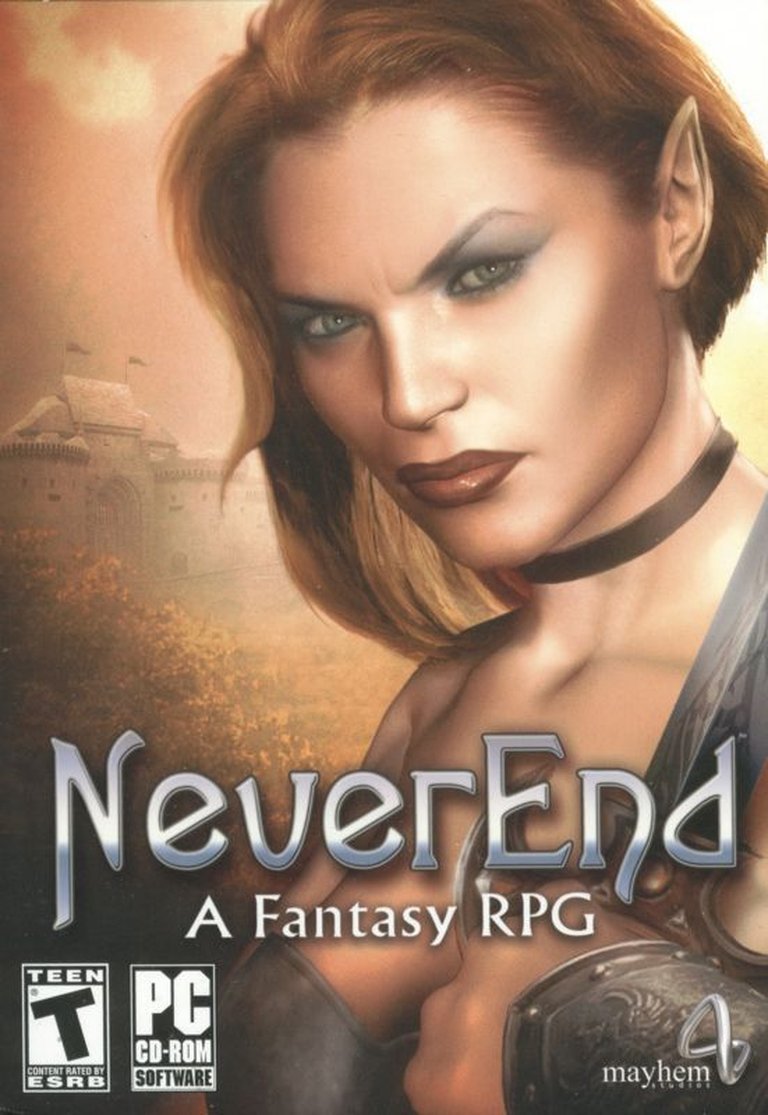

- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: DreamCatcher Interactive Inc., Dusk2Dawn Interactive Limited

- Developer: Mayhem Studios s.r.o.

- Genre: Role-playing

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Branching quests, Point-and-click, Puzzle elements, Spell creation, Sword combat, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 95/100

Description

NeverEnd is a fantasy turn-based RPG where players assume the role of Agavaen, a fallen fairy with magical powers, on a quest to uncover her true identity. The game features a branching quest system that determines her moral alignment as good or evil, a turn-based combat system with customizable spells via the RUNE mechanic, and the option to focus on sword combat, all presented through a point-and-click interface in an immersive fantasy setting.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy NeverEnd

NeverEnd Free Download

NeverEnd Patches & Updates

NeverEnd Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (91/100): The game reminded me of a graphic animated adventure, had arena-style, turn-based combat, and an interesting exploration system.

metacritic.com (100/100): Nostalgia… It was a good game for my younger self—I loved it. But now, I don’t know. It’s probably bad.

NeverEnd: A Fairy Tale Forged in Frustration — The Definitive Historical Review

In the vast, often-overlooked archives of mid-2000s PC gaming, few titles embody the era’s ambition, constraint, and ultimate compromise quite like NeverEnd. Released in 2006 by Slovakian studio Mayhem Studios and published by DreamCatcher Interactive, this turn-based fantasy RPG arrived with a quiet thud, a title seemingly plucked from a different design epoch and awkwardly transplanted into a market captivated by the open-world revolutions of Oblivion and Gothic 3. Its critical reception, a starkly divided 50% on MobyGames, mirrors a fundamental schism: was NeverEnd a creatively bold, story-driven JRPG-inspired gem buried under technical rubble, or a clumsy, dated relic that betrayed its own promising concepts? This review will argue that NeverEnd is unequivocally the former—a deeply flawed but substantively fascinating game. Its true value lies not in its polished execution, which was notoriously poor, but in its audacious attempt to graft Japanese-style RPG mechanics and narrative structures onto a Western-developed point-and-click framework, all while exploring a somber, personal fantasy of identity and exile. It is a game that is perpetually at war with itself, and in that conflict, reveals more about the transitional state of the RPG genre in 2006 than many of its acclaimed contemporaries.

Development History & Context: A Slovakian Studio’s Quixotic Quest

NeverEnd was the product of Mayhem Studios s.r.o., a Bratislava-based developer with a portfolio notably light on RPGs prior to this project. Led by Game Director Tomas Bencik and Designer/Writer Slavo Hazucha, the studio’s previous work included titles like Safecracker: The Ultimate Puzzle Adventure and Secret Files: Tunguska—point-and-click adventures and puzzle games. This pedigree is crucial to understanding NeverEnd’s DNA. The team was not venturing from a foundation of complex, systemic RPGs like Fallout or Baldur’s Gate, but from a tradition of narrative-driven, mouse-centric adventure games. Their vision, as described in promotional materials, was to create a “graphic animated adventure” with JRPG-style turn-based combat and a branching morality system.

The technological and market context of 2005-2006 is equally vital. On PC, the RPG landscape was bifurcated. One branch was dominated by Bethesda’s Morrowind (2002) and the looming Oblivion (2006), which championed real-time, first-person, open-world exploration. The other was the evergreen tradition of isometric, party-based CRPGs like Neverwinter Nights 2 (2006) and Gothic 3 (2006). The console-style, protagonist-centric, turn-based JRPG—epitomized by Final Fantasy X or Chrono Trigger—had a negligible presence on the PC outside of emulation or ports like Xenosaga. NeverEnd attempted to fill this niche, but with a Western adventure-game sensibility. Its pre-rendered, fixed-camera backgrounds and point-and-click interface immediately marked it as an anachronism in an era racing toward fully 3D, real-time worlds. This was not a limitation of budget alone, but a deliberate, if misguided, design choice to evoke a specific, story-heavy feel.

The development process appears to have been rocky. Multiple reviews, notably from German magazines PC Action and PC Games, cite an “insane initial difficulty” and a rushed beta, suggesting crunch and inadequate balancing. The notorious “swamp bug”—a crash-to-desktop error that rendered a critical area impassable in unpatched versions—is documented on TV Tropes and in user reports, pointing to serious QA shortcomings. The game was also slated for an Xbox release (Q2 2004 per Neoseeker), which was ultimately canceled. This abandoned console version hints at the team’s aspirations and the financial pressures that likely forced a compromised, PC-focused release. NeverEnd is, therefore, a snapshot of a small Eastern European studio attempting to compete on a global stage with a hybrid genre game, hampered by technical limitations and a market moving rapidly in other directions.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Burden of Being Other

The narrative of NeverEnd is its most praised and sophisticated element, a melancholic fairy tale that uses RPG mechanics to explore themes of identity, prejudice, and moral choice. The protagonist, Agavaen, is a “fallen fairy” of the Auren race, a winged, humanoid people banished from their home realm. Her defining trait is her “otherness.” Humans fear and despise her, seeing her as a witch. Even among the bandits she reluctantly joined, she is an outcast. The inciting incident—the theft of her magical amulet (the last physical link to the Auren) by her treacherous comrades—is less about material loss and more about the severing of her last vestige of identity and belonging.

The plot structure is deceptively simple: track down the thieves, retrieve the amulet, then discover her true self. However, the branching quest system and Conviction meter (Good/Evil) transform this linear quest into a character study. As detailed in the GameBoomers review and TV Tropes, the game is “dosed” with story fragments. The world-building is revealed slowly: the Auren are not mere “elves” but a specific, fallen race. The human kingdom is ruled by the Benevolent Mage Ruler, Sarthaan, a classic wizard figure who long ago defeated the evil Enakhaan. Yet, a La Résistance movement, the Dawners, believes Sarthaan is the source of the world’s monsters. This political and historical ambiguity prevents the story from becoming a simplistic good-vs-evil tale.

The thematic core is Agavaen’s search for home and self. The “Memento MacGuffin” amulet triggers her journey, but the real quest is internal. Her interactions—whether to show mercy or cruelty, help or exploit—visually alter her appearance (“White Hair, Black Heart” for the evil path). This is not a superficial change; it’s a direct manifestation of her internal corruption or purity. The Last-Second Ending Choice, which completely overrides her prior Conviction, is a masterstroke (or flaw) of design. The final decision to attack or aid Sarthaan determines the ending:

* Good Ending: She helps Sarthaan defeat her sister Denevera (a Dark Action Girl), is restored as a true fairy, and returns to the Auren realm.

* Evil Ending: She allies with Denevera to kill Sarthaan, summon a monster army, and Take Over the City.

This binary, with “No Points for Neutrality”, forces a philosophical conclusion. The narrative argues that for an outcast like Agavaen, there is no middle path; she must actively choose integration and goodness or embrace destructive nihilism and tyranny. The story’s power is in this personal, tragic scale, a stark contrast to the world-saving epicism common in the genre. It’s a story about a single fairy’s soul, not the fate of kingdoms.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Combat System in Search of a Coherent Framework

If the narrative is NeverEnd’s heart, its gameplay is its perpetually ailing liver. The systems are a pile of ambitious, often contradictory ideas, struggling under the weight of poor implementation and balancing.

1. The Turn-Based “Arena” Combat: As noted by almost every reviewer, combat is arena-style and turn-based, but with an “Active Time Battle” (ATB)-like sliding initiative scale based on Agavaen’s and the enemy’s Agility, Strength, Endurance, and Level. Each attack type (quick jab vs. heavy overhead slash) has a different “step” cost, determining who acts next. This creates tactical depth—faster, weaker attacks let you strike more often. However, as the GameBoomers review astutely observes, Agility becomes the “One Stat to Rule Them All.” Since running away, drinking potions, and even bleeding effects all consume time steps, investing in Agility to act first and most often is overwhelmingly optimal, making other stats (like the Dump Stat, Perception, which only slightly affects turn order and crit chance) largely irrelevant. This hollows out character build diversity.

2. The RUNE Spell System: This is NeverEnd’s most touted innovation and its greatest gameplay failure. Spells are not learned via mana pools but crafted from collected runes (small, color-coded icons) in a specific sequence (the “recipe”). The concept—player-created spells—is brilliant. The execution, per the GameBoomers and GameSpot reviews, is abysmal. Runes are tiny, colors are similar, and clicking the wrong runes destroys them from your inventory. Spell components are consumed on cast, forcing constant re-collection. The system is tedious, unintuitive, and brutally punishing for error. Furthermore, spells are useless outside battle, and many enemies (like ghosts) are immune to physical attacks, forcing reliance on this broken system. The reviewers’ consensus is correct: a traditional mana system would have been vastly superior.

3. Difficulty, Random Encounters, and Progression: The game’s difficulty curve is infamous. German magazines reported an “insane” starting difficulty where Agavaen is repeatedly slain by random wolves and bandits until she gains a few levels. This is exacerbated by excessive random encounters on the overworld map, a point of constant frustration in reviews from PC Powerplay and ComputerGames.ro. These encounters often pit her against wildly overpowered foes, making exploration a chore. Progression comes from experience points from battles and quest completion, with gold用于 purchasing armor and potions. The unlimited inventory is a welcome, if unusual, QoL feature. The three difficulty levels (Easy, Normal, Hard) attempt to mitigate this, but the core issue of balancing remains fatal.

4. Quest Design and the Karma Meter: Here, NeverEnd shines. Quests are varied and creative (solving an invisible demon’s theft, navigating love triangles, town politics). The branching nature is genuine; accepting or rejecting quests, and how you resolve them (diplomatically, violently, deceptively), shifts the Conviction meter. This is not a hidden meter but one signaled by on-screen visual cues. Your final alignment determines the ending, providing strong replay value, as noted by Next Level Gaming. The quests themselves feel like they belong in an adventure game, with conversation, inventory, and battle solutions, perfectly marrying the developer’s background to the RPG format.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Study in Artistic Dissonance

The world of NeverEnd is a place of starkly uneven beauty, a technical compromise that occasionally achieves a strange, nostalgic charm.

Visuals and Art Direction: The game uses pre-rendered, fixed-camera backgrounds for towns and dungeons, with 3D character models moving atop them. This was a dated technique in 2006, immediately making the game feel like a leftover from the late 90s (“graphics straight out of a decade-old golf game” as GameSpot cruelly noted). The environments range from bland and repetitive forests to strikingly colorful and detailed areas (as praised by GameBoomers for “intensely colored detailed fauna”). The creature design is a high point. Enemies are not generic orcs but imaginative variants of the Auren—”Cute Monster Girls” with wings and colored skin—alongside skeletons (“Dem Bones”) and other fantasy fare. Their animations are notably non-wooden, with stylish, varied attack motions. Agavaen’s own model changes visibly for the evil path (white hair, exotic markings), and the end cinematic is repeatedly called “gorgeous.”

However, the camera system is a mess. Angles shift arbitrarily, sometimes blocking the view with trees during combat. Entering a room can flip your orientation, causing disorientation. The “Male Gaze” is overt in several fixed angles that emphasize Agavaen’s figure. The “Stripperiffic” Body Tattoo armor (tight leather, lace) underscores this. The character portraits in the UI are also criticized, with some reviewers (ComputerGames.ro) suggesting they might be photos of the developers themselves, lending a bizarre, amateurish feel.

Sound Design: The orchestral soundtrack is widely considered a strength, with a medieval flair and pleasant, wind-carried flute melodies during exploration. Battle music is less acclaimed but functional. The voice acting, however, is a catastrophic weak point. Reviews across the spectrum (GameBoomers, 4Players.de) lambaste it as ranging from “adequate” to “totally abysmal,” with cases of “Ooh, Me Accent’s Slipping” as actors portray multiple roles. The lead voice of Agavaen is often cited as “Dull Surprise,” failing to convey the character’s emotional turmoil. This dissonance—between occasionally beautiful music and frequently terrible voice acting—undermines the serious narrative tone.

UI and Interface: The point-and-click interface is functional but clunky. The map (pressed with “M”) is essential due to the limited view and confusing layouts, but finding hidden items is “hit or miss.” The “not alt/tab friendly” issue and crashes (reported 7 times by one reviewer) are major, game-breaking flaws. The inability to depict party members on the field (relying on portrait icons) further breaks immersion.

Reception & Legacy: The Bargain Bin Sisyphus

NeverEnd’s launch was a quiet commercial failure. Its Metascore of 44 (“Generally Unfavorable”) on Metacritic, based on 13 critic reviews, tells the story. The critic breakdown is brutal: only one positive review (91% from Just Adventure), a few mixed (70-74%), and a torrent of negatives (48% and below from PC Zone, GameSpot, Game Chronicles, PC Gamer UK). The praise ($\text{Just Adventure}$’s “graphic animated adventure,” $\text{Next Level Gaming}$’s “good ideas like the battle system”) is almost always caveated with “if you can get past the graphics/technical issues.” The negativity is absolute: $\text{GameSpot}$ calls it “as modern as the telegram,” $\text{Game Chronicles}$ says playing it made them wish it would “die a quick, merciful death,” and $\text{GameShark}$ declared it “0%”—an “unmitigated mess.”

Its legacy is that of a cult curiosity and a cautionary tale. It never achieved the “discovered gem” status of something like Arcanum or Planescape: Torment because its flaws were too pervasive and its core mechanics too uneven. It has not influenced major developers. Instead, its legacy is textbook:

1. The Perils of Hybrid Design: It demonstrates the extreme difficulty of mashing together point-and-click adventure pacing, JRPG combat, and Western RPG morality systems without creating a Frankenstein’s monster of conflicting rhythms.

2. The Non-Negotiable Need for Polish: No amount of narrative ambition or interesting system design can overcome game-breaking bugs, a broken spell-crafting interface, and severe balancing issues. Players will abandon a beautiful idea if the act of engaging with it is frustrating.

3. A Snapshot of Regional Development: It stands as a artifact of the vibrant butunder-supported Eastern European indie scene of the 2000s, where talented teams with niche visions often lacked the resources for the polish expected by Western audiences.

4. The “Bargain Bin” Lifespan: Its inclusion in compilations like Hall of Game: 4Games – Volume 6 (2006) confirms its status as filler content—a title used to pad a budget collection because it had no standalone market value.

Yet, it retains a small, passionate defender base. User scores on MobyGames (3.8/5) and NeoSeeker are notably higher than critic scores, with comments citing nostalgia (“It was my first PC game I bought”), affection for the fairy aesthetic, and appreciation for its “vibe” and turn-based combat. For these players, NeverEnd is a flawed friend, not a masterpiece.

Conclusion: The Never-Ending Cycle of Ambition and Failure

NeverEnd is not a good game by any conventional metric. Its technical execution is frequently disastrous, its UI is archaic, its voice acting is laughable, and its central RUNE spell system is a design misfire. To the critic in 2006, comparing it to Oblivion or even Dungeon Siege II, it was rightly panned as a relic.

But to judge it solely on those terms is to miss its historical and design significance. As a historian, NeverEnd is a profoundly important case study. It is the clearest possible document of a team trying to make a very specific type of game—a slow, narrative-heavy, protagonist-centric fantasy with a moral core—using the tools and paradigms of adventure game development. Its story, of a persecuted being seeking identity, is treated with a sincerity rarely found in the “chosen one” epics of its day. Its quests, though buried under layers of jank, are creative and consequential.

Its place in history is not as a classic, but as a warning and a witness. It warns of the fatal consequences of releasing an unpolished product in a competitive market. It witnesses the struggle of a non-Japanese studio to internalize and replicate the JRPG format, a struggle that would later see more success with games like The Legend of Heroes: Trails series on Western PCs. NeverEnd is the awkward, bug-ridden prototype that had to exist for others to learn from.

In the final analysis, NeverEnd is a failed experiment that contains the seeds of a better, unrealized game. Its heart—a tale of fairy exile with player-driven morality—is in the right place. Its mind—the strategic combat and branching paths—has potential. But its body—the code, the interface, the audio—is wracked with dysfunction. It is the video game equivalent of a beautiful, hand-bound book whose pages are stuck together, whose ink is smudged, and whose chapters are out of order. You can see the beauty of the story meant to be told, but the act of reading it is an act of frustration. For that reason, it is best left to historians, completionists, and those with a high tolerance for jank—a fascinating “what if” tombstone in the cemetery of 2006 RPGs. Its name, NeverEnd, becomes cruelly ironic: for most players, the experience will feel endless in all the wrong ways, a loop of frustration with no satisfying conclusion. Yet, for the few who push through, it offers a haunting, personal fantasy that few games of its era dared to attempt.