- Release Year: 2009

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Det Danske Akademi for Digital, Interaktiv Underholdning Filmskolen

- Developer: Det Danske Akademi for Digital, Interaktiv Underholdning Filmskolen

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Exploration, Hack and Slash

- Setting: Horror, Playground, School

Description

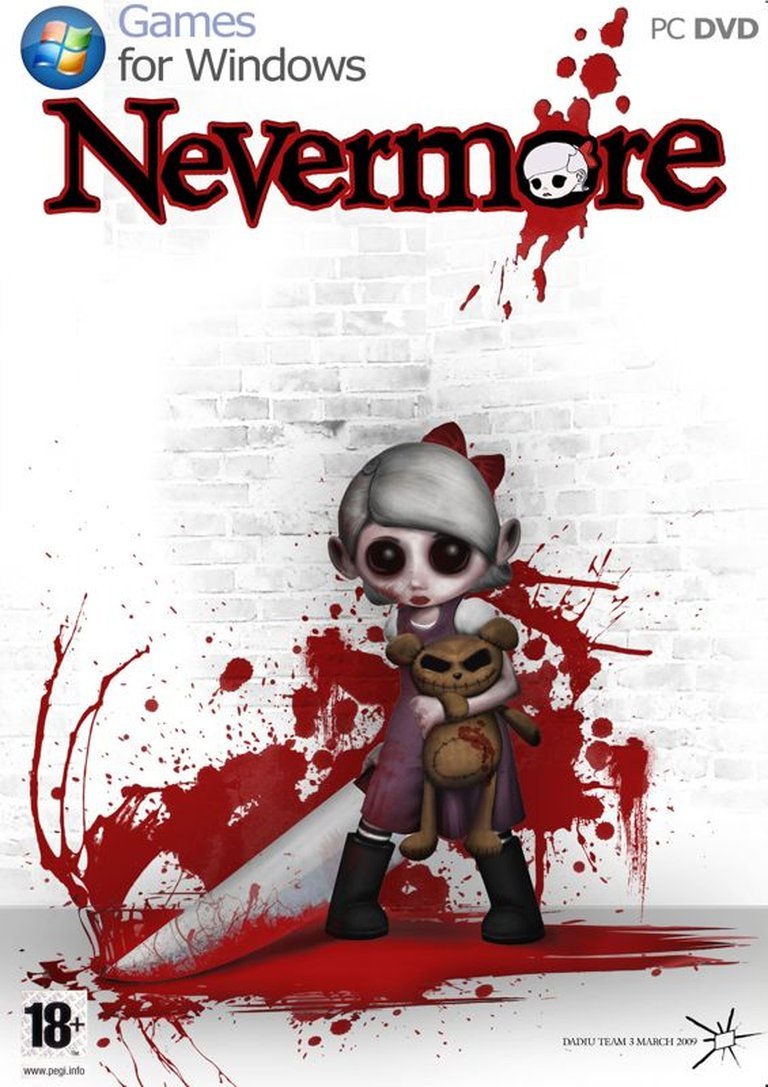

Nevermore is a short, freeware action-horror game set in a school playground where young Anna, bullied by her peers, follows her teddy bear Mr. Huggles’ twisted advice to collect ‘red paint’ (blood) from bullies by slashing them open with a sword and using Mr. Huggles to soak up the gore. With only five minutes before the school bell rings, Anna must explore the playground, dodge attacks, and fill a blood meter to draw a hopscotch diagram, all while enduring the teddy bear’s unsettling encouragement.

Where to Buy Nevermore

PC

Nevermore Patches & Updates

Nevermore: A Disturbing Dive into Childhood’s Darkest Corners

Introduction

In the pantheon of video games that dare to explore the fragility of innocence, Nevermore stands as a singular, haunting artifact. Released in 2009 by the experimental Danish collective Det Danske Akademi for Digital, Interaktiv Underholdning Filmskolen, this freeware action title recontextualizes playground cruelty through a lens of visceral body horror. Its premise—where a bullied child, Anna, slays her peers to harvest their blood for hopscotch paint—immediately positions it as a transgressive commentary on trauma and the corruption of childhood. While its runtime is brief (a mere five minutes), Nevermore achieves a profound, lasting impact through its unflinching execution. This review deconstructs Nevermore not as a conventional game, but as a provocative piece of interactive art that weaponizes gameplay mechanics to dissect psychological pain. Its legacy endures as a testament to games’ capacity to confront discomfort, making it a crucial, albeit niche, entry in the medium’s history.

Development History & Context

Nevermore emerged from Copenhagen’s nascent independent game scene, where the Det Danske Akademi—a student-led film and interactive arts collective—sought to push boundaries beyond mainstream gaming. Director Troels Cederholm and designer Michelle Maria Langkilde envisioned a project that merged Unity’s accessible 3D capabilities with raw, uncompromising themes. The team of 14, including lead programmer Dannie Korsgaard and composer Andreas Arenholt Bindslev, operated under strict constraints: a shoestring budget (resulting in freeware distribution) and a 2009 release date that predated Unity’s widespread adoption for complex narrative games.

Culturally, Nevermore arrived amid a surge of indie darlings (e.g., Braid, World of Goo), yet it deliberately eschewed the trend of “whimsical” experimentation. Instead, it reflected a Scandinavian tradition of dark, socially critical art—reminiscent of Lars von Trier’s films or the works of playwrights like Jon Fosse. Its PEGI 18 rating underscored its unapologetic content, while its Mac/Windows dual release emphasized its academic origins. This context is vital: Nevermore was never intended as entertainment, but as a provocative statement on how childhood violence festers beneath normalized cruelty.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative unfolds with brutal simplicity: Anna, a young girl tormented by bullies, seeks solace in her teddy bear, Mr. Huggles. He proposes a “solution”: she must play hopscotch, but to draw the chalk diagram, she needs red paint. Mr. Huggles insidiously suggests the bullies “stole” the paint and now store it “inside their bodies.” This euphemism for blood launches the game’s core horror: Anna must violently slit open her aggressors to collect their fluids. The dialogue—a grotesque inversion of childhood comfort—exposes the monstrous logic of trauma. Mr. Huggles’ saccharine encouragement (“Slicey-slicey, Anna! Now Mr. Huggles needs a drink!“) twists nurturing into predation, symbolizing how abuse can internalize self-destructive coping mechanisms.

The five-minute timer imposes relentless pressure, mirroring the cyclical nature of bullying. The bullies themselves are dehumanized clones, differentiated only by shirt color (indicating strength), reducing them to targets. Yet, this stripping of identity makes Anna’s actions more disturbing; she is not fighting monsters, but peers. The game’s climax—Anna drawing a hopscotch diagram with blood—turns a symbol of youthful joy into a macabre ritual of reclamation. Thematically, Nevermore critiques the normalization of violence: it suggests that when societal systems fail the vulnerable, they are forced to adopt the very brutality inflicted upon them. The absence of redemption or catharsis leaves players complicit in Anna’s descent, forcing an uncomfortable confrontation with the banality of evil.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Nevermore’s gameplay is a minimalist exercise in tension. As Anna, players navigate a school playground with three core actions: a standard sword slash, a heavy attack, and a jump to evade kicks. Combat is fluid but weightless, lacking the depth of traditional hack-and-slash games. Instead, the emphasis is resource management: after defeating a bully, players must hold Mr. Huggles aloft to “soak” blood into a meter. This mechanic transforms gore into a functional currency, with each splash of blood deducting from the pool if Anna takes damage—a direct metaphor for how trauma depletes emotional reserves.

The UI is starkly utilitarian: a timer dominates the screen, while the blood meter pulses ominously. Exploration is limited but purposeful, as players must balance hunting victims with reaching a statue to complete the hopscotch diagram. The game’s genius lies in its systemic cohesion: the timer creates urgency, combat is streamlined to discourage prolonged engagement, and the blood meter punishes failure. However, these systems also expose flaws: repetitive enemy designs and a punishing difficulty spike (due to time constraints) can feel frustrating. Yet, this frustration is intentional, mirroring the helplessness of a child trapped in a violent cycle.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Nevermore’s world is a stylized, purgatorial playground. Built in Unity, the environment is rendered in muted, desaturated tones—grays, browns, and sickly reds—that evoke a decaying institution. The schoolyard is devoid of life save Anna and her victims, its empty swings and slide amplifying isolation. Character design is deliberately grotesque: the bullies are lanky, identical figures with blank stares, while Anna, rendered with childlike proportions, wields a comically oversized sword, heightening the absurdity of her violence.

Sound design is the game’s most potent element. Andreas Arenholt Bindslev’s score is a dissonant mix of nursery rhyme melodies and industrial noise, warping childhood into dread. Mr. Huggles’ voice—voiced by Tue Toft Sørensen—alternates between sugary encouragement and guttural whispers, his voice acting blurring the line between toy and tormentor. The visceral squelches of combat and the rhythmic drip-drip of blood collection are amplified to sensory overload, making the playground feel like a slaughterhouse. This audiovisual fusion creates an atmosphere of psychological unease, where every giggle hides a scream, and every game is a survival tactic.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Nevermore polarized audiences. Mainstream outlets largely ignored it, while niche communities debated its merits. MobyGames archives reveal a modest player base (collected by 5 users), with an average score of 3.3/5 based on two ratings. Some criticized its brevity and jank, but others lauded its courage. The Lemma Soft Forums discussion thread highlighted its “unflinching” approach, though one user noted it felt “more like an art installation than a game.” Its legacy is thus confined to underground circles, cited in academic papers on game violence and trauma.

Influence is subtle but tangible. Nevermore predates games like Undertale and Fran Bow in using gameplay to subvert expectations of childlike innocence. Its focus on systemic critique (rather than shock value) echoes titles like This War of Mine and Papers, Please. However, its extreme content limits its accessibility, ensuring it remains a cult artifact—a footnote in gaming history that nonetheless forces reflection on the medium’s responsibility to challenge players.

Conclusion

Nevermore is not a game one “enjoys.” It is an experience one endures, a five-minute descent into the abyss of a child’s psyche. As a piece of interactive art, it masterfully weaponizes mechanics to dissect trauma, transforming hack-and-slash combat into a metaphor for self-destructive coping. Its flaws—repetitive gameplay, technical roughness—are overshadowed by its fearless narrative ambition. While its legacy is confined to a niche audience, its impact is undeniable: Nevermore proves that games can be vessels for uncomfortable truths, forcing players to confront the monsters hiding in plain sight. In a medium often criticized for sanitizing violence, Nevermore stands as a dark, vital reminder that some scars never heal—and that the most profound stories are often the ones we least want to tell.