- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Anglia Multimedia Ltd.

- Developer: Black Sheep Design

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Platform

- Setting: Fantasy

- VR Support: Yes

Description

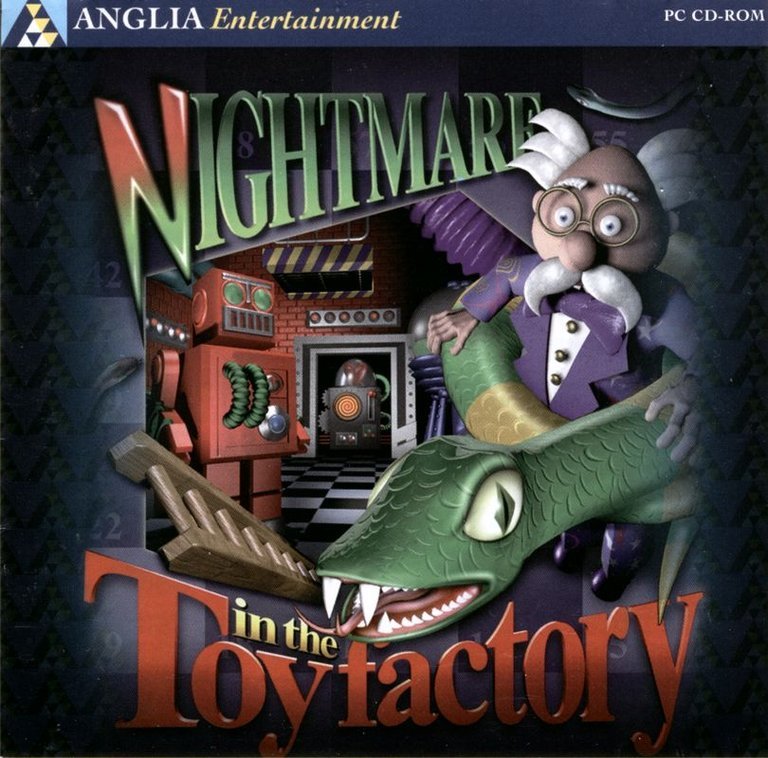

Nightmare in the Toyfactory is a 3D platform game for kids where players must build a toy hero to rescue Professor Wizz-Bang, who disappeared the night before Christmas, threatening the delivery of presents. The game features six story-based areas filled with traps, platform challenges, and 25 mini-games like Arkanoid and Tetris, all rendered in 3D graphics with a fully rotatable camera.

Gameplay Videos

Nightmare in the Toyfactory Reviews & Reception

collectionchamber.blogspot.com : Ultimately, the controls are too fiddly, the platforming too imprecise and the game just a little too weird. A curiosity, not a classic.

Nightmare in the Toyfactory: Review

Introduction

Released in 1997, Nightmare in the Toyfactory stands as a perplexing artifact of the early 3D gaming era—a Christmas-themed platformer for children that veers unexpectedly into surreal, even unsettling territory. Developed by Black Sheep Design and published by Anglia Multimedia, this Windows-exclusive title promises whimsy but delivers an experience defined by technical ambition colliding with jarring execution. Its legacy is one of cult curiosity rather than mainstream acclaim, remembered for its bizarre premise (a giant snake kidnaps a toy professor) and idiosyncratic blend of platforming and mini-games. This review deconstructs Nightmare in the Toyfactory as a product of its time, examining its design choices, thematic dissonance, and enduring enigma within video game history. Ultimately, the game reveals itself as a flawed, fascinating experiment—a digital nightmare wrapped in festive paper.

Development History & Context

Emerging from the United Kingdom’s burgeoning edutainment scene of the mid-90s, Nightmare in the Toyfactory was a product of Anglia Multimedia, a publisher known for educational titles like The Pink Panther: Passport to Peril. Developer Black Sheep Design, though obscure even in contemporary archives, aimed to leverage emerging 3D technologies on a budget. Released for Windows 95, the game arrived amid a pivotal moment: the industry’s transition from 2D sprites to polygonal 3D, epitomized by titles like Super Mario 64 and Tomb Raider. Yet Nightmare eschewed true 3D for a hybrid approach, using pre-rendered 360° backgrounds with scalable sprites and voxels—a clever workaround for the era’s hardware constraints (16MB RAM, SVGA graphics). Its ELSPA 3+ rating signaled a target audience of children, but its tone—juxtaposing holiday cheer with industrial dread and a serpentine villain—suggested a fractured creative vision. The game’s limited physical release (primarily in the UK) and CD-ROM medium underscored its niche status, positioning it as a budget title rather than AAA contender.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The premise is deceptively simple: On Christmas Eve, Professor Wizz-Bang, a toy inventor, is kidnapped by the Crawling King Snake, who threatens to devour him and cancel Christmas. The player “builds” a toy hero to traverse six factory-themed areas and rescue him. Yet the narrative’s execution unravels into tonal chaos. The villain’s motivations are unexplained beyond generic villainy, while the game’s Christmas motifs feel superficial—reduced to scattered collectibles (presents) and the snake’s absurd “bah, humbug!” taunt. The dialogue is sparse and devoid of charm, failing to engage its young audience. Thematically, the game juxtaposes innocence and terror uneasily: Toy-like protagonists battle industrial robots and antibodies in a labyrinthine factory, evoking Toy Story-esque wonder but undercut by mechanical dread. Professor Wizz-Bang’s role as a damsel-in-distress reinforces outdated tropes, while the snake’s design—a hulking, scaly monstrosity—clashes with the supposed fantasy setting. The result is a narrative that feels less like a cohesive story and more like a fever dream: whimsical yet alienating, festive yet ominous.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Nightmare in the Toyfactory’s core loop is a platformer burdened by clumsy execution. Players navigate 50 levels across six areas (e.g., “Basement,” “Snake’s Belly”), jumping between ill-defined platforms while avoiding traps like robots and antibodies. The control scheme is infamously unwieldy: A combination of keyboard and mouse inputs results in delayed jumps and imprecise movement, exacerbated by the engine’s reliance on sprites over polygons. Character creation is a shallow gimmick—players assemble a hero from pre-made “gizmos” (e.g., springs, wheels) but cannot customize behavior. This leads to homogenous playthroughs, undermining replayability. The game’s saving grace is its 25 mini-games, including Arkanoid, Tetris, and tank battles. These diversions, often triggered by collecting presents, reuse the pre-rendered 3D engine with greater success. One mini-game even functions as a sandbox art tool, showcasing latent creativity. However, the main game’s difficulty spikes disproportionately for children, with pixel-perfect jumps and obtuse level design. UI navigation is clunky, and the “3D camera” rotation—while technically innovative—serves little practical purpose, often obscuring platforms. Ultimately, the gameplay feels like a series of disconnected ideas bound by technical compromise.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The factory setting is the game’s most compelling element, rendered with surprising detail despite its limitations. Levels progress from the grimy basement to the snake’s organic interior, using pre-rendered backgrounds to create convincing depth. Voxels and sprites mimic industrial machinery (conveyor belts, presses) and organic textures (scales, mucus), resulting in a world that is both fantastical and grotesque. The Crawling King Snake’s domain is a standout, with pulsating walls and fleshy corridors that subvert holiday cheer into body horror. Yet art direction is inconsistent: Toy characters look generic, while environments oscillate between charming (holiday-themed rooms) and unnerving (antibody-filled corridors). Sound design similarly splits moods: Upbeat CD audio tracks clash with dissonant sound effects (grinding gears, hissing snakes). The snake’s vocalization—a guttural roar—feels misplaced in a “kid’s” game. The 3D camera, while technically allowing 360° rotation, is impractical for gameplay, forcing players to squint into a small screen corner. This visual tunneling undermines world immersion, turning exploration into a chore. Despite these flaws, the art’s ambition—blurring line between toybox and dystopian factory—leaves an indelible, if disquieting, impression.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Nightmare in the Toyfactory met with near-universal indifference. CD-Action awarded a brutal 40%, criticizing its “drobiazgów” (roughly, “minutiae”) that “poil efekt,” rendering gameplay unenjoyable. Players echoed this frustration, with a MobyGames user rating averaging 1.0/5. Commercially, it faded into obscurity, its limited release preventing widespread notoriety. Yet, time has cultivated a cult following. Retrospectives highlight its technical ingenuity—pre-rendered backgrounds paving the way for future pseudo-3D experiments—and its surreal tonal dissonance, which predates the “toy horror” subgenre (e.g., Five Nights at Freddy’s). Reddit threads recall childhood terror at the snake’s design, while preservationists like The Collection Chamber emphasize its historical curiosity. The game’s 25 mini-games, particularly the art sandbox, are noted as ahead-of-their-time diversions. Despite this, Nightmare left no direct industry impact; it remains a footnote, cited more for its weirdness than its innovations. Its legacy is one of cautionary tale—a reminder that technical ambition without cohesive vision creates nightmares, not magic.

Conclusion

Nightmare in the Toyfactory is a fascinating failure, a relic of 1997’s 3D frontier where ambition outpaced execution. Its narrative tonal whiplash—from festive to horrifying—and jarring gameplay reflect a studio grappling with new technology and an uncertain audience. Yet, it cannot be dismissed as mere shovelware. Black Sheep Design’s inventive use of pre-rendered environments and the sheer novelty of 25 mini-games reveal flashes of brilliance. The game’s enduring appeal lies in its unsettling charm: a Christmas story wrapped in industrial dread, where a giant snake’s roar echoes louder than jingle bells. For historians, it’s a case study in the era’s experimental design; for players, it’s an artifact of digital surrealism. While its 40% critical score is deserved, Nightmare in the Toyfactory transcends its flaws as a curio—a nightmare worth revisiting, if only to understand the strange alchemy of gaming’s awkward adolescence. It is, in the end, less a toy and more a time capsule, capturing a moment when pixels collided with peril, and Christmas almost didn’t come.