Description

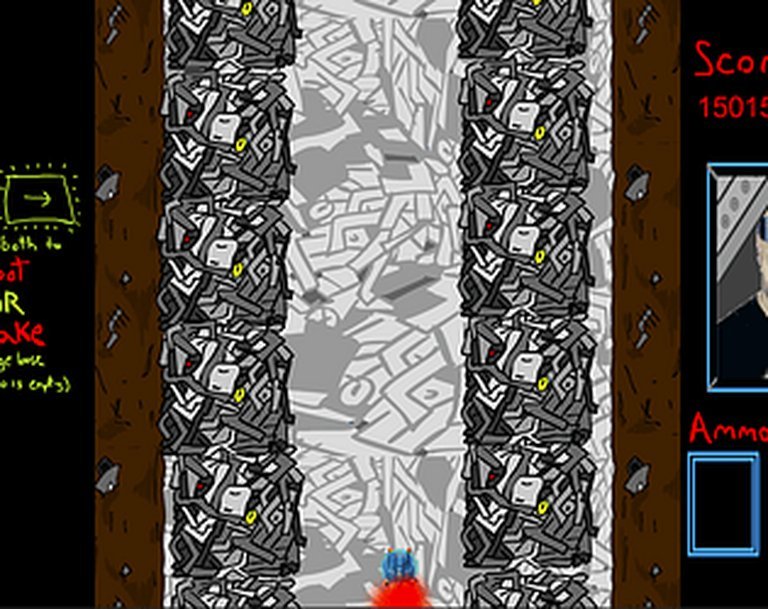

Nuclear Arms 2: Garbage Day is a top-down, 2D scrolling arcade shooter set in a sci-fi universe, created as part of the Ludum Dare 34 game jam. Players control Craig Killbane’s spaceship using a unique two-button control scheme (left and right arrow keys) to navigate through infinite procedurally generated levels filled with space garbage. The core gameplay involves avoiding trash that causes your ship to grow larger, shooting lasers to clear paths, collecting shields for protection, and managing powerups while receiving radio call-ins from friends and enemies throughout the comedic space adventure.

Crack, Patches & Mods

Nuclear Arms 2: Garbage Day: A Ludum Dare Relic’s Journey Through Infinite Space Junk

Introduction

In the vast cosmos of video game history, most titles are destined to be forgotten asteroids, burning up in the atmosphere of public consciousness. Yet, some, like the bizarrely compelling Nuclear Arms 2: Garbage Day, are worth retrieving from the junk pile for a closer examination. Developed in a frantic 48-hour burst for the Ludum Dare 34 game jam, this top-down, infinite space shooter is a fascinating artifact of indie development constraints meeting creative ambition. It is a game built on a paradox: a narrative about the epic adventures of a space pilot named Craig Killbane, yet mechanically centered on the Sisyphean task of avoiding cosmic trash. This review will argue that Garbage Day, while mechanically simplistic and visually unrefined, is a perfect case study of the game jam ethos—a raw, unfiltered burst of creativity where innovative design constraints and a bizarre comedic-thriller premise collide to create something uniquely memorable.

Development History & Context

To understand Nuclear Arms 2: Garbage Day, one must first understand the crucible in which it was forged: the Ludum Dare game jam. The theme for the 34th iteration in December 2016 was “Two Button Controls” and “Growing.” This restrictive theme was not a suggestion but a challenge, a creative straitjacket designed to force innovation through limitation.

The development team, a consistent quartet of Logan Marks, Mitchell Maclean, Chad Gerein, and Brodie Beaman, operated under the studio name Logicon211. This was not their first rodeo; they were veterans of the jam scene, having released the first Nuclear Arms for Ludum Dare 32 and would go on to create an astonishingly prolific, if obscure, series of sequels including Nuclear Arms 3 (2016), Nuclear Arms 5: Orphan Overdrive (2018), and Nuclear Arms 6: Waste Wizard’s Tricks (2018). Their continued collaboration suggests a well-oiled, if small, machine capable of dividing labor efficiently under extreme time pressure.

Technologically, the game was built using the Unity engine, the workhorse of indie game jams due to its accessibility and rapid prototyping capabilities. The decision to release simultaneously on Windows, Macintosh, Linux, and Browser (HTML5) platforms speaks to Unity’s cross-platform strengths and the developers’ desire for maximum accessibility. The game was distributed exclusively through itch.io, the digital storefront that has become the de facto home for such jam creations, priced at a consumer-friendly $0.00.

The gaming landscape of late 2016 was dominated by AAA blockbusters like Battlefield 1 and Final Fantasy XV. Yet, beneath the surface, the indie scene was thriving, with titles like Stardew Valley proving that small teams could achieve massive success. Garbage Day exists in a different stratum altogether—the pure, uncommercialized realm of game jams, where the goal isn’t sales but the successful execution of a creative idea against a brutal deadline. It is a digital sketch, a proof-of-concept born from a weekend of caffeine-fueled coding and asset creation.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of Nuclear Arms 2: Garbage Day is a masterclass in audacious juxtaposition. The game’s official MobyGames descriptors list its narrative genres as “Comedy” and “Thriller,” a combination that perfectly encapsulates its tonal chaos.

The protagonist is one Craig Killbane, a name that evokes the gravitas of a 1980s action hero. Players of the first game (a prerequisite the developers gently encourage) would presumably be familiar with his ongoing saga. The premise is brilliantly absurd: a spacefaring hero, presumably engaged in intergalactic conflict as suggested by the series title “Nuclear Arms,” is suddenly and utterly consumed by the mundane problem of waste management. The primary antagonist is not an alien armada but floating garbage, and the core mechanic—”growing” upon collision with trash—transforms the hero’s journey into a tragicomic tale of bloat and encumbrance.

The narrative is delivered through what the credits call “Conversation panel logic and UI,” handled by Mitchell Maclean, and “Recorded and edited VO lines,” courtesy of Brodie Beaman. This implies a layer of storytelling beyond the core gameplay, with radio call-ins from “friends and enemies” that presumably comment on Craig’s increasingly dire, garbage-clogged situation. The inclusion of a “HYPERDRIVE” activation—shouted in all-caps in the official description—hints at a moment of triumphant escape, a narrative payoff to the endless cycle of avoidance.

Thematically, the game is a bizarre allegory. It explores growth not as a positive form of progression (like leveling up) but as a punitive, physically limiting state. In this universe, you literally are what you eat—or in this case, what you collide with. The accumulation of “garbage” slows you down, makes you a larger target, and ultimately leads to your demise. One can read into this a sharp critique of consumerism, environmental collapse, or simply the exhausting accumulation of life’s mundane burdens. It’s a thriller not because of espionage or danger, but because the slow, inevitable approach of clutter is, to many, a very real and palpable anxiety.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The genius of Garbage Day is in its elegant, theme-driven adherence to the Ludum Dare constraints. The entire experience is governed by a control scheme using only the left and right arrow keys, a purist’s interpretation of “Two Button Controls.”

- Core Loop: The player pilots a spaceship from a top-down perspective in an endlessly scrolling field of space junk. The objective is survival. The core loop is a tense ballet of avoidance and management.

- The “Growing” Mechanic: This is the heart of the game. Colliding with floating trash doesn’t cause immediate damage; instead, it causes your ship to “grow.” This is a clever and punishing twist. A larger ship is harder to maneuver, has a larger hitbox, and becomes progressively more susceptible to further collisions, creating a vicious cycle of decline.

- Resource Management & Tools: The player has two key tools to break this cycle:

- Lazers: By pressing both arrow keys simultaneously (if they have ammo), the ship fires a laser to blast a path through the garbage. This is the primary offensive and defensive tool.

- Shaking Loose: If the ship has become too encumbered, holding both arrow keys together allows the pilot to “shake garbage loose,” presumably reducing size and regaining maneuverability.

- Shields: Pickups allow the ship to endure collision obstacles, providing a temporary respite from the growth mechanic.

- Progression & The Hyperdrive: The promised “HYPERDRIVE” activation suggests a high-risk, high-reward mechanic, perhaps a speed boost or screen-clearing ability that serves as a ultimate goal or a last-ditch escape plan.

The UI, as credited to Mitchell Maclean, must therefore display crucial information: laser ammo, shield status, ship size, and the conversation panels from the supporting cast. This creates a layered experience where the player is simultaneously navigating a physical threat and a narrative one, listening to the taunts and advice of off-screen characters.

The “infinite” or “endless runner” design means there is no final level, only a high score. The game is a test of endurance and skill within its perfectly defined, minimalist ruleset. Its flaw, inherent to its jam nature, is likely a lack of depth; the mechanics, while brilliant, may not evolve significantly over time, risking repetition. But as a focused experiment, it is a resounding success.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Given its 48-hour development cycle, Nuclear Arms 2: Garbage Day’s aesthetic is necessarily minimalist and functional. The credits list multiple contributors to “some art,” indicating a shared, rushed effort to visualize this bizarre universe.

The game employs a 2D scrolling visual style from a top-down perspective. The setting is the void of space, but it is a space cluttered with the detritus of civilization, transforming the final frontier into a cosmic landfill. The art direction had to clearly communicate several key elements: the player’s ship (which changes size), the dangerous garbage, beneficial power-ups like shields, and the laser beams.

The sound design, handled by Mitchell Maclean, is crucial. In a game with such simple visuals, audio cues are paramount. The player must hear the collision with trash, the firing of the laser, the activation of the shield, and the shaking loose of garbage. Furthermore, the recorded voice-over lines by Brodie Beaman are not just narrative flair; they are a key part of the world-building. The “call ins of your friends and enemies” provide auditory texture and personality, pulling the player into Craig Killbane’s world and adding a layer of comedy to the thrilling escape.

The atmosphere is therefore one of frantic, claustrophobic comedy. It’s not the terrifying claustrophobia of a horror game, but the exasperating claustrophobia of a space that is filling up with junk faster than you can clear it. The juxtaposition of epic space opera sounds (lasers, hyperdrives, radio chatter) with the mundane subject matter (garbage day) is the primary source of its unique charm and humor.

Reception & Legacy

As of its entry into the MobyGames database in 2025, Nuclear Arms 2: Garbage Day has a Moby Score of “n/a” and is “Collected By” only one player. There are no critic or user reviews on the platform. This obscurity is its defining characteristic.

Its reception is not measured in sales figures or Metacritic scores, but in its existence as a completed jam submission. Its success is defined by its completion and its adherence to the theme. In this, it is a triumph.

Its true legacy is twofold. First, it serves as a historical marker in the prolific, if niche, Nuclear Arms series, a testament to the enduring creative partnership of its developers. Second, and more importantly, it stands as a perfect exhibit in the museum of game jam design. It is a textbook example of how to:

1. Interpret a theme literally and mechanically (“Growing” means your ship gets bigger).

2. Build a complete, functional game loop under extreme constraints.

3. Inject narrative and humor into a simple concept to enhance its appeal.

While it did not influence the industry at large, it embodies the spirit of a thousand such jam games that collectively form the fertile training ground where developers hone their skills and experiment with ideas too weird for the mainstream market.

Conclusion

Nuclear Arms 2: Garbage Day is not a “good game” in the traditional, polished sense of the word. It is a rough-edged, mechanically simplistic, and visually rudimentary artifact. To judge it by those standards, however, is to miss the point entirely.

It is a brilliant game jam artifact. It is a captivating case study in innovation under constraint, a wonderfully absurd narrative concept, and a perfectly executed proof-of-concept for its two-theme premise. It represents the unadorned, passionate core of game development: a small team, a crazy idea, a deadline, and the drive to see it through. For historians and enthusiasts of game jams and indie development, Garbage Day is a priceless relic. It is a reminder that before the sprawling open worlds and cinematic narratives, a game can be something as simple, stupid, and sublime as a spaceship trying to avoid trash, growing fatter and more frustrated with every collision. Its place in history is secure not on a pedestal, but in the archive—a glorious piece of cosmic junk waiting to be rediscovered.