- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Midian Design

- Developer: Midian Design

- Genre: Adventure, Horror

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Inventory management, Point-and-click, Puzzle-solving

- Setting: Detective, Horror, Mystery, Paranormal

- Average Score: 43/100

Description

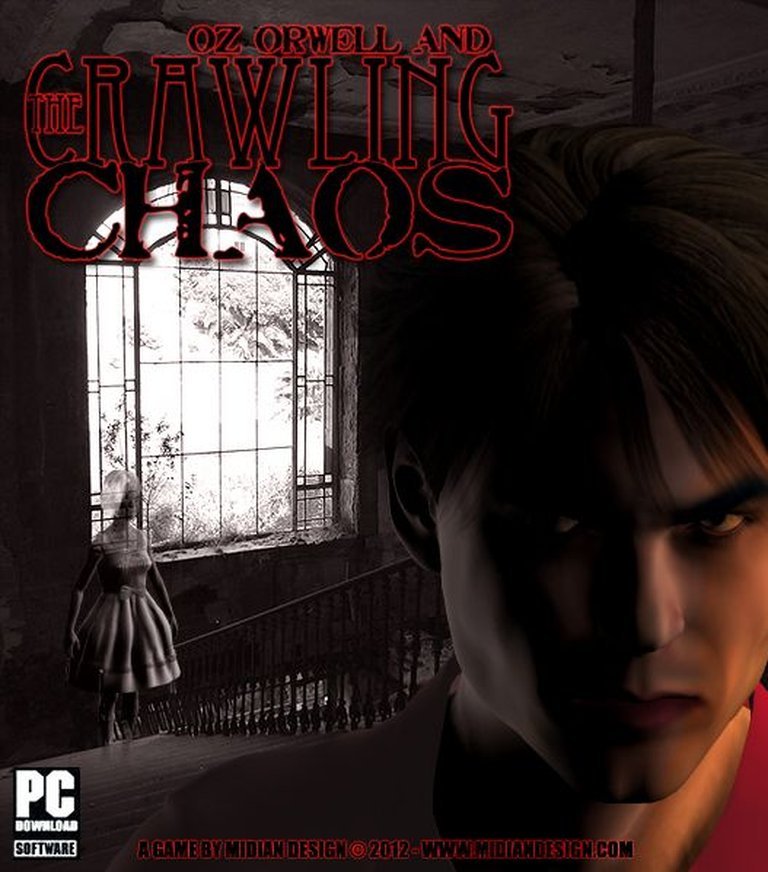

In Oz Orwell and the Crawling Chaos, you play as Oz Orwell, a ghost investigator who has yet to find real evidence of hauntings. Your latest case brings you to the Angst Mansion in Italy, where you must use point-and-click mechanics to interact with the environment, collect clues, and solve puzzles to uncover the mansion’s dark secrets.

Gameplay Videos

Oz Orwell and the Crawling Chaos Guides & Walkthroughs

Oz Orwell and the Crawling Chaos Reviews & Reception

gameboomers.com : I was drawn into the Angst Mansion’s eerie atmosphere and felt a mounting curiosity as to the dread secrets that Oz was bound to unearth.

adventuregamers.com : You will be genuinely surprised by the ending, but it will also seem like a natural conclusion once all the pieces are in place.

adventureclassicgaming.com : Oz Orwell and the Crawling Chaos is a psychological thriller from Danilo Cagliari of Midian Design.

vognetwork.com : This makes it really simple to play, but also really boring for people that are probably not into these types of games.

Oz Orwell and the Crawling Chaos: A Deep Dive into a Lovecraftian Point-and-Click Adventure

Introduction

In the shadowed corridors of indie horror gaming, few titles manage to evoke the existential dread of H.P. Lovecraft while retaining the intimate, puzzle-solving charm of classic point-and-click adventures. Released in July 2012 by Italian developer Midian Design, Oz Orwell and the Crawling Chaos stands as a fascinating, if polarizing, artifact of this niche. Players step into the worn shoes of Oz Orwell—a self-proclaimed ghost investigator and admitted fraud—whose investigation into the haunted Angst Mansion in Italy spirals into a Kafkaesque nightmare of trapped corridors, spectral whispers, and a conspiracy that challenges his sanity. More than just a haunted house simulator, this game is a psychological labyrinth where reality and nightmare blur, and the “Crawling Chaos” lies not in the ghosts themselves, but in the uncanny truths Oz uncovers. This review deconstructs Midian Design’s ambitious creation, examining its narrative depth, mechanical design, atmospheric craft, and enduring legacy within the pantheon of indie horror.

Development History & Context

The Studio and Vision

Oz Orwell and the Crawling Chaos is the brainchild of Danilo Cagliari, the sole proprietor of Midian Design—a micro-studio operating from Italy. Cagliari served as the game’s programmer, artist, animator, musician, and sound designer, with testing and localization support from a small team: Arjon van Dam (“Arj0n”), Flavio Soldani, Pan, and Paul Giaccone. This hyper-efficient solo development ethos was typical of the Adventure Game Studio (AGS) scene, where creators often wore multiple hats to realize their visions on shoestring budgets. Cagliari’s goal was clear: to craft a Lovecraftian horror adventure that blended supernatural mystery with detective intrigue, eschewing jump scares for slow-burn psychological unease. The game’s premise—a cynical skeptic confronting genuine, reality-warping evil—reflects a creative tension between genre tropes and subversive storytelling.

Technological Constraints and the AGS Engine

Built on the freeware Adventure Game Studio engine, Oz Orwell inherited both the strengths and limitations of this aging platform. AGS (version 3.3) enabled point-and-click mechanics and pre-rendered graphics but constrained the game to 2D environments with rudimentary sprite animation. Cagliari mitigated these constraints by creating detailed, “naturalistic” backgrounds inspired by Italian Renaissance architecture, though the engine’s inability to support dynamic lighting or fluid character movement resulted in stiff animations and static scenes. The game’s technical requirements were modest: a 1.0 GHz processor, 512 MB RAM, and a 128 MB DirectX 9.0 graphics card, ensuring accessibility on older hardware. However, the reliance on external file archiving (e.g., .RAR format requiring WinRAR or 7-Zip) for distribution and the lack of a built-in installer highlighted the era’s indie-distribution challenges.

The Gaming Landscape in 2012

2012 was a pivotal year for narrative-driven games. While AAA titles like Mass Effect 3 dominated headlines, the indie scene was exploding with titles like Journey and Fez. However, the point-and-click revival, spearheaded by Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead, had raised standards for voice acting, cinematic pacing, and player choice. Against this backdrop, Oz Orwell’s deliberate retro aesthetic—with no voice acting (barring a muffled opening cutscene), minimalist UI, and linear puzzles—felt intentionally anachronistic. It positioned itself not as a modern blockbuster, but as a love letter to 90s classics like The Black Mirror or Sanitarium, emphasizing atmosphere over interactivity. This niche appeal alienated some players but endeared others to its purist vision of classic adventuring.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot and Character: The Descent of a Charlatan

The narrative unfolds over four claustrophobic days as Oz Orwell, trapped in the Angst Mansion, uncovers layers of horror that transcend ghostly apparitions. The plot begins deceptively simply: Oz, desperate to debunk his critics, enters the mansion seeking proof of the supernatural. Instead, he finds himself imprisoned by a vanishing door and tormented by spectral phenomena—a floating kitchen knife impaling a cryptic note, a blood-filled bathtub with a rising hand, and a sentient carousel spinning without a child. These events, however, are mere preludes to a darker truth. As Oz delves into the mansion’s history via a haunted diary, he learns of its builder, Cornelius Angst—a man obsessed with a “Door of Dreams” that bridges worlds. The narrative then pivots from haunted-house tropes to a meta-horror revelation: the ghosts are manifestations of Oz’s own repressed guilt and drug-induced psychosis, and the “Crawling Chaos” is his unraveling sanity.

Characterization is the narrative’s core strength. Oz is a deeply flawed antihero—a cynical opportunist whose morbid humor (“Okay, he’s a fraud but, hey, it’s a living!“) masks a fragile psyche. His interactions with the mansion’s spectral inhabitants—particularly Zoe, a ghostly child offering cryptic advice—humanize him even as his actions grow increasingly disturbing. The ghosts are not mere jump-scare devices but psychological mirrors: the man in wheelchair embodies Oz’s guilt over a past accident, while the upside-down sleeper represents his nightmares. The dialogue, delivered through text boxes, balances bleak wit with existential dread, especially in Oz’s internal monologues. As Adventure Classic Gaming noted, the story “throws twist after twist” culminating in a finale that recontextualizes every prior event, forcing players to question whether Oz is a victim, a villain, or both.

Themes: Sanity, Reality, and Lovecraftian Dread

The game’s thematic core is the fragility of perception. Midian Design weaves Lovecraftian elements not through tentacled monstrosities, but through the horror of incomprehensible truths. The “Crawling Chaos”—a term borrowed from Lovecraft’s short story—epitomizes this: it is not an external entity but the slow erosion of Oz’s grip on reality. Themes of guilt and addiction permeate the narrative, with Oz’s drug use implied as a catalyst for his hallucinations. The dream sequences, rendered in stark black and white, are visceral explorations of his psyche: Giger-esque landscapes of crucifixion and organic horror symbolize his self-punishment and fear. As Adventure Gamers observed, these sequences “tap into the fears of each dreamer,” making the mansion a character in its own right—a projection of collective trauma.

The setting also serves a thematic function. The Angst Mansion, with its bricked-up windows and shifting corridors, becomes a metaphor for Oz’s mental prison. Its Italian roots add a layer of gothic grandeur, contrasting with Oz’s modern, cynical persona. The story’s most daring theme is the blurring of victim and perpetrator. By the end, players realize Oz may have orchestrated the mansion’s hauntings to exploit his audience, a twist that critiques the commodification of fear in media. This meta-commentary elevates the game beyond mere horror, positioning it as a meditation on authenticity, exploitation, and the nature of belief.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Mechanics: Point-and-Click Puzzle-Solving

Oz Orwell adheres strictly to classic point-and-click conventions. Players guide Oz through static third-person scenes using left-clicks for movement and interaction, and right-clicks for examining objects. The interface is minimalist: an inventory bar appears at the bottom of the screen when hovered over, allowing item combination or hotspot application. Puzzles fall into three categories: environmental interaction (e.g., finding keys in drawers), dialogue-based choices (e.g., interrogating ghosts to elicit clues), and abstract challenges like the “tuning fork puzzle” where players must sequence musical notes. While the absence of combat or death aligns with the game’s psychological focus, it also removes tension, making frustration the primary risk—especially when players hit dead-ends.

Design Flaws: Pixel Hunting and Ambiguity

The gameplay’s Achilles’ heel is its punitive design. Pixel hunting—searching for nearly invisible hotspots—is rampant, particularly in the black-and-white dream sequences. As GameBoomers’ reviewer Becky noted, players must “paint the screen” for objects “snuggling atop the laps of other hotspots.” The lack of a hotspot indicator or journal exacerbates this, leading to aimless wandering. Inventory management is another pain point: the game holds up to 40 items, but many are red herrings, forcing players to resort to trial-and-error combinations. Puzzles often lack sufficient clues, such as a riddle requiring keyboard input with no contextual hints. For example, one early puzzle demands players decipher a fridge note, but without clear direction, players may spend hours clicking incoherently. The “interrogation scene” is similarly obtuse, relying on guesswork rather than deduction.

Strengths: Atmosphere and Pacing

Despite these flaws, certain mechanics shine. The dream sequences, accessed via the “Door of Dreams,” break up the mansion’s monotony with surreal, self-contained puzzles. These sections prioritize symbolism over logic, requiring players to interpret imagery (e.g., a Giger-inspired “birth canal” scene) to advance—a bold departure from traditional adventuring. The pacing, initially slow, builds effectively as Oz’s investigation intensifies. The brisk walking speed (noted by Adventure Classic Gaming) prevents tedious backtracking, and the linear structure, while restrictive, maintains narrative momentum. The absence of time limits or fail states creates a contemplative experience, letting players soak in the atmosphere—a choice that aligns with the game’s psychological themes.

UI and Technical Execution

The UI is functional but dated. Text-based dialogue dominates, with speech bubbles appearing on the left side of the screen. While the Italian-to-English localization is polished (Adventure Classic Gaming noted “no spelling mistakes”), the lack of voice acting (outside the garbled opening) distances players from characters. Save slots are abundant, mimicking Sierra-style nostalgia, but the reliance on the Escape key for access feels archaic. Technically, the game is stable but unsophisticated: pre-rendered backgrounds offer rich detail (e.g., decaying mosaics, antique furniture), but character sprites are stiff, with repetitive walking animations. Cutscenes, though artistically ambitious, suffer from low resolution due to AGS limitations.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Atmosphere and Setting: The Angst Mansion as Character

The Angst Mansion is the game’s crowning achievement, a masterclass in environmental storytelling. Its Italian Renaissance architecture—marble floors, grand staircases, frescoed ceilings—collides with decay: peeling wallpaper, cobwebs, and ominous shadows. The “Hill of Shadows” setting amplifies the gothic dread, with fog-draped exteriors and moonlit courtyards evoking classic horror films. The mansion’s design is a metaphor for Oz’s psyche: lavish but crumbling, beautiful but haunted. The dream portals are equally striking, transforming into grotesque tableaux: a chapel dripping with viscera, a forest of teeth, and a crucifixion scene where Oz becomes the victim. These sequences, inspired by H.R. Giger and Zdzisław Beksiński, abandon realism for surrealism, using black-and-white photography to enhance unease. As Adventure Gamers described, they border on “the horrific and the bizarre,” ensuring no two environments feel alike.

Art Direction: Naturalism with a Surreal Edge

Visually, Oz Orwell walks a line between naturalism and surrealism. Cagliari’s backgrounds are meticulously detailed, with photorealistic textures on wood and stone. This “naturalistic” approach, as GameBoomers noted, contrasts with pixelated retro adventures, creating a sense of tangible space. Yet, the art falters in execution: static backgrounds lack ambient animation (e.g., swaying curtains or drifting fog), making scenes feel like dioramas. Character design is inconsistent; Oz’s sprite (jeans, red shirt) is expressive but lacks the fluidity of hand-drawn animations, while ghosts appear as ethereal overlays, their movement limited to floating or blinking. The dream sequences redeem this, using monochrome palettes and distorted perspectives to evoke psychological horror. A standout moment involves a bath of blood, rendered in grimy detail with a hand emerging from the depths—a visceral image that lingers long after gameplay ends.

Sound Design: Ambience Over Fidelity

The soundtrack is the game’s most polished element, blending orchestral and MIDI compositions to heighten dread. Ludwig van Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata recurs, its C# minor notes amplifying the mansion’s gloom. Original tracks, moody and minimalist, underscore key moments without overwhelming subtlety. Sound effects, however, are sparse but effective: dripping water, distant footsteps, and the buzz of flies near a corpse create auditory texture. The absence of voice acting (barring the muffled opening) is a missed opportunity; while text-based dialogue preserves the game’s retro charm, it prevents emotional connection with characters. Voice of Geeks criticized the music as “repetitive and generic,” yet Adventure Gamers praised it as “excellent,” highlighting the subjective nature of its impact. Ultimately, the sound design prioritizes atmosphere over fidelity, using silence as a tool to unsettle players before a sudden jolt of audio.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Reception: A Tale of Two Reviews

Upon release, Oz Orwell garnered a schismatic reception. Critics either lauded its ambition or lamented its execution. Adventure Gamers awarded it 70%, calling it “arguably Midian Design’s best game to date” that “overcomes its lack of production polish with a fascinating horror / paranormal detective story.” The review highlighted the “enticing atmospheric soundtrack” and “spine-tingling apparitions” as strengths, while criticizing “limited animation” and “insufficient clues for certain puzzles.” Conversely, Voice of Geeks lambasted it with a 16% score, deeming it a “really big disappointment” due to “boring gameplay, mediocre graphics, and terrible music.” Players were similarly divided, with a MobyGames average of 3.6/5 reflecting moderate appreciation. These polarized responses underscored the game’s identity: a cult title for horror adventure enthusiasts but a hard sell for mainstream audiences.

Commercial Performance and Evolution

Commercially, Oz Orwell was a niche success. Priced at $3.99, it attracted budget-conscious fans of point-and-clicks, with its low entry point mitigating criticism. Midian Design sold it via direct download (BMT Micro), a common strategy for indie developers at the time. The game’s legacy persists through its sequel, Oz Orwell and the Exorcist (2016), which refined mechanics but retained the Lovecraftian tone. Within the AGS community, Oz Orwell is remembered for pushing engine boundaries—particularly in dream sequence design. It also influenced subsequent indie horrors, like Saint Kotar: The Crawling Man (2022), which embraced surreal psychological themes. However, its reputation remains that of a “flawed gem”: admired for its narrative bravery but criticized for technical datedness.

Long-Term Influence

In retrospect, Oz Orwell represents a transitional moment in indie horror. It bridged the gap between the Sierra-style adventures of the 90s and the narrative-driven games of the 2010s, proving that low-budget titles could tackle mature themes. The game’s exploration of unreliable narrators and psychological dread anticipated trends in titles like Layers of Fear (2016). Its emphasis on atmosphere over action also resonated with the “walking simulator” subgenre. Yet, its technical constraints—pixel hunting, lack of voice acting—date it, making it more a historical curiosity than a timeless classic. As Adventure Classic Gaming concluded, it is “a surprisingly competent indie adventure” whose flaws are “outweighed by its strengths” for patient players.

Conclusion

Oz Orwell and the Crawling Chaos is an enigma—a game of striking contrasts that oscillates between brilliance and frustration. Its narrative ambition, Lovecraftian themes, and atmospheric artistry elevate it above typical indie fare, crafting a psychological horror experience that lingers in the mind. Yet, these strengths are hampered by mechanical roughness: punitive pixel hunting, obtuse puzzles, and technical limitations rooted in its AGS foundation. The game succeeds not as a flawless masterpiece, but as a testament to the power of restraint—proving that dread can be more potent than gore, and that a compelling story can transcend graphical imperfection. For fans of classic adventures and Lovecraftian tales, Oz Orwell is a worthwhile journey, offering four hours of creeping unease and a finale that redefines “haunted.” Its legacy, though modest, endures as a bold, if flawed, entry in the canon of indie horror—a reminder that sometimes, the most unsettling monsters are the ones we carry within. Final Verdict: A B-, a game that may not satisfy all, but will haunt the right player.