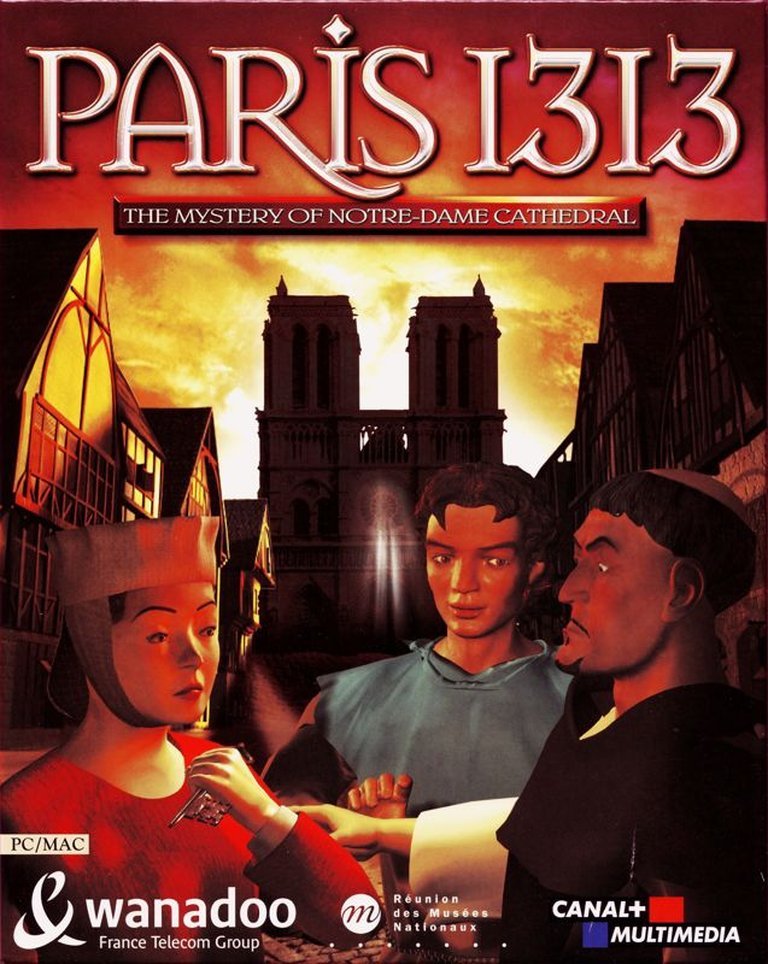

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Canal+Multimédia, France Télécom Multimédia, index, MC2-Microïds, Réunion des Musées Nationaux

- Developer: Dramæra

- Genre: Adventure, Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Point-and-click, Puzzle

- Setting: City – Paris, Country – France, Fantasy, Medieval Europe

Description

Paris 1313: The Mystery of Notre-Dame Cathedral is an educational adventure game set in medieval Paris, where players investigate a mysterious accident at the iconic Notre-Dame cathedral by controlling three characters—Jacques a goldsmith, Pierre a horseman, and Rosemonde a dancer—through point-and-click gameplay, puzzle-solving, and arcade-like sequences, all woven into a detective narrative with historical insights.

Gameplay Videos

Paris 1313: The Mystery of Notre-Dame Cathedral Cracks & Fixes

Paris 1313: The Mystery of Notre-Dame Cathedral Guides & Walkthroughs

Paris 1313: The Mystery of Notre-Dame Cathedral – A Timely Relic of Edutainment’s Ambition

1. Introduction: A Cathedral of Contradictions

In the late 1990s, the video game landscape was bifurcating. On one side, the 3D revolution promised immersive worlds; on the other, a venerable tradition of narrative-driven, 2D point-and-click adventures persisted, often infused with educational intent. It is from this latter lineage—and a uniquely Franco-European collaboration—that Paris 1313: The Mystery of Notre-Dame Cathedral emerges. Released in 1999 by the consortium of index+, Canal+Multimédia, France Télécom Multimédia, and MC2-Microïds, with critical scientific supervision from the Musée National du Moyen Age, the game is a fascinating artifact. It is a title deeply committed to historical verisimilitude and immersive atmosphere yet shackled by the repetitive puzzle design and technical constraints of its era. My thesis is this: Paris 1313 is not a forgotten classic by any measure, but it is a crucial, earnest, and ultimately revealing case study in the ambitions and pitfalls of the “edutainment” adventure genre at the close of the 20th century. Its legacy is not one of direct influence, but of a specific, museum-bound vision of interactive history that has no true modern equivalent.

2. Development History & Context: A Nation-Backed Project

The game’s development under the banner of Dramæra was less a venture of a single studio and more a state- and institution-supported cultural project. The involvement of the Réunion des Musées Nationaux and the Musée National du Moyen Age (Cluny) as scientific directors and supervisors was not merely advisory; it was foundational. Pierre-Yves Le Pogam from the Cluny museum is credited as Scientific Director, and a team provided documentation and editing of a “documentary space” within the game. This formal partnership ensured that the setting—Paris in 1313—was rendered with a fidelity that went beyond aesthetic pastiche. It was an attempt at virtual heritage, allowing players to navigate a historically-grounded medieval city during the reign of Philip IV.

Technologically, the game sits at an awkward crossroads. It utilized pre-rendered backgrounds with 2D sprites and animated cutscenes, a standard for adventure games of the period but one that was already being eclipsed by true 3D exploration elsewhere. The decision to fit the entire experience on a single CD-ROM is cited by a critic from Tap-Repeatedly/Four Fat Chicks as a probable cause for “cut corners,” leading to repetitive scenes—a significant constraint for a game aiming for breadth. The development landscape of 1999 was dominated by titles like Grim Fandango (1998) and Syberia (2002), which pushed narrative and visual style, and Myst-clone puzzle adventures. Paris 1313 did not compete with these on gameplay innovation; its primary competition was the realm of educational software and historical simulations, where it sought to blend entertainment with a guided tour of the past.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Clockmaker’s Disappearance

The plot, while straightforward, is intricately woven into the historical context. The inciting incident is the mysterious disappearance of Adam, a goldsmith working for the king, during celebrations before Notre-Dame Cathedral. This is not a generic whodunit; the narrative’s core MacGuffin is explicitly identified as “the making of the first mechanical clock.” This clue ties the mystery directly to a landmark technological innovation of the medieval period, elevating the stakes from a simple missing person case to one involving royal secrets, guild politics, and nascent technology.

Players assume the roles of three distinct protagonists, each with a personal stake and unique access to different parts of Parisian society:

1. Jacques: Adam’s brother, a young goldsmith. His perspective grounds the story in the artisan guilds and the immediate family shock.

2. Pierre de Cinnq-Ormes: A horseman aspiring to join the King’s Army. His storyline provides access to military circles, the nobility, and the urban outskirts, including an arcade-like archery contest.

3. Rosemonde: A dancer (or actress, per some sources). Her role is crucial for navigating the taverns and more disreputable quarters of Paris, gathering gossip and information from a cross-section of urban life unavailable to the other two.

The narrative structure is chapter-based and interdependent. Advancement requires performing specific tasks with at least two characters, forcing the player to switch perspectives and combine clues gathered from disparate social spheres. This design reinforces the theme of a multifaceted, interconnected medieval society. The dialogue, scripted by François Nédélec, likely aimed for a balance of period flavor and clarity, though the English translation is widely noted as haphazard and incomplete, a critical flaw that undoubtedly undermined the narrative immersion for non-French speakers. The underlying theme is one of investigative reconstruction—piecing together a lost truth from fragments found in diverse environments, mirroring the historian’s craft.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Click-and-Wait Syndrome

At its core, Paris 1313 is a classic point-and-click adventure. The gameplay loop is familiar: navigate 2D screens, converse with NPCs to gain information or new dialogue options, collect inventory items, and use them to solve environmental puzzles. The three-character switch is its central systemic innovation, but its implementation is telling. You don’t freely switch; you progress through a linear chapter structure, completing required tasks for each character in a prescribed order to unlock the next chapter. This creates a rigid, puzzle-box feel, where progress is gated not by skill but by the completion of specific, often repetitive, actions.

The puzzle design is the game’s most criticized element. Reviews from Adventure Classic Gaming (“overly simple or arbitrary”) and Jeuxvideo.com (“jouabilité est affreuse” – the playability is awful) highlight a fundamental disconnect. Puzzles often devolve into trial-and-error and excessive backtracking across identical-looking locations. The “arcade-like elements”—the chimney climb and archery practice—are noted as diversions but are reportedly clunky and feel tacked-on, breaking the adventure game rhythm rather than enhancing it. There is no combat system to speak of; conflict is resolved through dialogue, stealth, or puzzle-solving.

The User Interface is standard for the genre: a verb coin or menu for interactions (Look, Take, Talk, Use), and an inventory screen. No significant innovation is reported. The “documentary space,” a potential unique feature promised by the museum partnership, seems to have been an underdeveloped or culminating in-game resource rather than a dynamic system, failing to meaningfully alter the core gameplay loop. The game’s systems, therefore, represent a conservative, even dated, approach to adventure design, relying on player endurance rather than elegant design or logical puzzle coherence.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Unequivocal Strength

This is where Paris 1313 unequivocally succeeds and where its educational mission is most realized. The art direction, leveraging the pre-rendered technique, aims for a painterly, atmospheric representation of 1313 Paris. The screenshots and reviews consistently praise the “well-done graphics” and the sense of place. Key landmarks like Notre-Dame Cathedral (incomplete, as it was in 1313) are rendered with a weight and texture that conveys historical imagination. The color palette is muted, earthy, avoiding the bright, cartoonish look of some contemporaries, instead evoking a grimy, lived-in medieval city.

The sound design and music contribute heavily to this atmosphere. The game features voice-over work for all dialogue (in French, with the aforementioned problematic English dub) and a soundtrack that involves “music research and selection” by Denis Escudier, suggesting a attempt at period authenticity or mood-appropriate scoring. The voice acting, while not acclaimed as Oscar-worthy, is noted as part of the game’s solid production values in reviews like Tap-Repeatedly’s.

Together, the visuals and audio create a cohesive, immersive atmosphere that is the game’s saving grace. You are not playing a generic fantasy city; you are in a version of Paris that feels researched, dense with detail, and historically grounded. This world-building successfully transports the player, making the repetitive gameplay and weak puzzles easier to bear for those captivated by the setting. It is the primary argument for its value as a “brief medieval Paris vacation,” as Ray Ivey of Just Adventure charmingly put it.

6. Reception & Legacy: A Niche Curiosity

Paris 1313 received a lukewarm to poor critical reception upon release, holding a MobyGames average of 60% based on six critic reviews. The spectrum is wide:

* Positive (80%, 75%): Reviews like Tap-Repeatedly/Four Fat Chicks and Just Adventure acknowledge the strengths: the interesting三方叙事, the historical authenticity, the engaging story about clockmaking, and the excellent atmosphere. They recommend it to a niche audience: “those who love the Middle Ages” and have a “high threshold for frustration.”

* Negative (42%, 40%): PC Player (Germany) dismisses it as a “national[istic] history lesson” with the “charming appeal of an Arte theme night,” implying didactic dryness. Adventure Classic Gaming finds the puzzles uneven and arbitrary, undermining the experience.

* Middle (60%): Jeuxvideo.com and Quandary land in the middle, praising the graphics and documentary content but lambasting the poor playability and nonsensical challenge progression.

Commercially, it was a niche title, published in multiple languages but clearly aimed at the French and European markets. Its legacy is profoundly niche. It did not spawn sequels or inspire a wave of similar historically-accurate adventure games. Instead, it exists as a cul-de-sac in the edutainment genre. Unlike the more playful Carmen Sandiego or the puzzle-focused Myst, Paris 1313 attempted a serious, museum-grade immersion. It represents a moment when public cultural institutions (the French national museums, state-backed telecom and media companies) invested in interactive media as a vector for historical dissemination, a model less common today. Its modern presence is as abandonware, preserved by sites like My Abandonware and GOG (where it has appeared on user dreamlists), appreciated only by retro adventure connoisseurs and historians of the medium.

7. Conclusion: A Flawed Relic Worthy of Preservation

Paris 1313: The Mystery of Notre-Dame Cathedral is a game of stark contrasts. It is meticulously researched yet poorly translated. It presents a beautifully realized, atmospheric world yet traps the player in frustrating, repetitive puzzle loops. It ambitiously intertwines a detective mystery with a real historical technological milestone (the mechanical clock) yet structures its gameplay with frustrating linearity.

Its place in video game history is not that of a masterpiece, but of a significant document. It testifies to a specific late-90s European vision of what games could be: not just entertainment, but interactive museum exhibits and national heritage projects. Its failures are as instructive as its successes. The disconnect between its scholarly ambitions and its conventional, sometimes clumsy, adventure game execution highlights a persistent challenge in “serious games”: how to make learning an organic, enjoyable part of play rather than a competing layer.

For the modern player, approaching it requires managing expectations. Do not seek a streamlined adventure or a gripping thriller. Seek instead a slow, atmospheric trompe-l’œil of medieval Paris. Go for the joy of wandering a digitally reconstructed 1313, for the intrigue of a mystery tied to the very foundations of clockwork, and for the insight into an era when major media companies and national museums saw video games as a legitimate cultural frontier. By those metrics, Paris 1313 remains, flaws and all, a fascinating and worthwhile excavation.

Final Verdict: 6.5/10 – A historically precious but mechanically tedious artifact, essential for understanding the scope and limitations of late-period edutainment adventures. Play it for the world, endure it for the story.