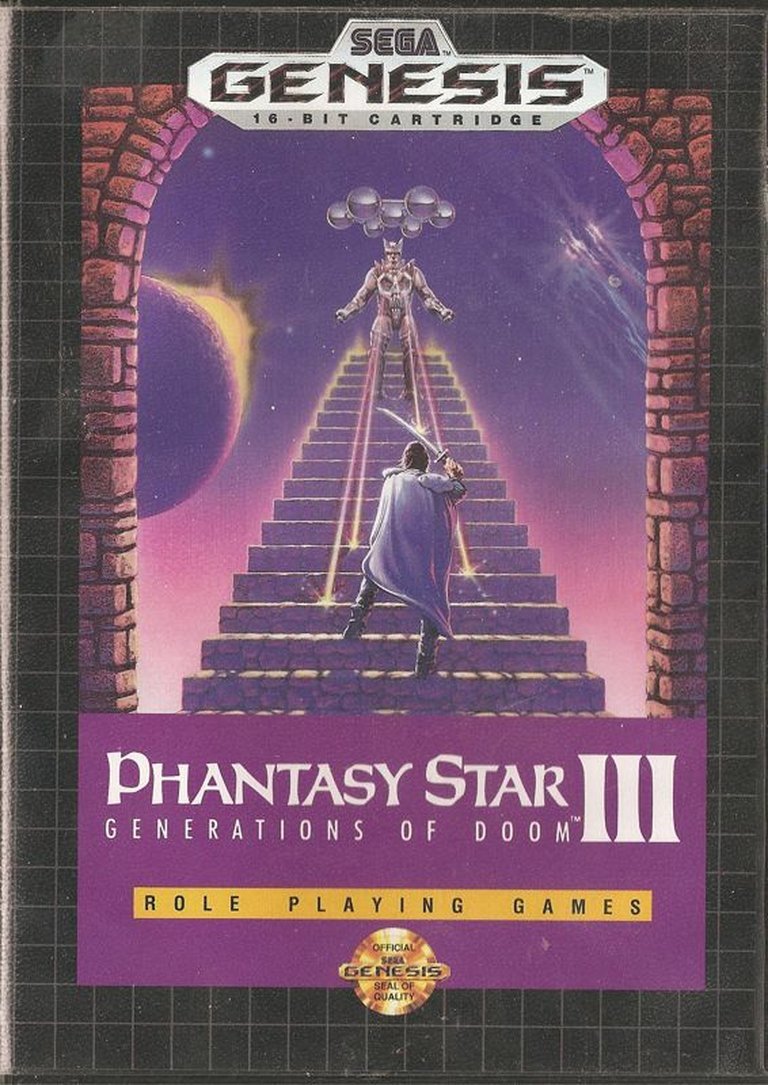

- Release Year: 1990

- Platforms: Genesis, Linux, Macintosh, Wii, Windows

- Publisher: SEGA Enterprises Ltd., SEGA Europe Ltd., SEGA of America, Inc., Tec Toy Indústria de Brinquedos S.A.

- Developer: SEGA Enterprises Ltd.

- Genre: Role-playing, RPG

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: 2D dungeons, Branching paths, Generation system, Party programming, Random encounters, Technique distribution, Top-down exploration, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 65/100

Description

Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom is a role-playing game set in a medieval fantasy world recovering from a thousand-year-old war between the Orakian and Layan factions. The story begins with Prince Rhys’s attempt to rescue his kidnapped bride, Maya, and evolves across three generations of his family, with player choices determining branching narratives and gradually introducing sci-fi elements to the setting.

Gameplay Videos

Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom Free Download

Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom Patches & Updates

Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom Mods

Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom Guides & Walkthroughs

Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom Reviews & Reception

ign.com (65/100): The least compelling entry in an otherwise stellar RPG series.

mobygames.com : Unanimity sucks, Phantasy Star III doesn’t.

rpgranked.com : Mediocrity manifested

Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom Cheats & Codes

Sega Genesis / Mega Drive

Enter codes using Game Genie or Action Replay devices before starting the game.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| ETBA-AA88 | Master code, must be entered |

| AWAA-CA7A | 1st treasure chest contains specified amount plus 32,768 meseta |

| 9MTA-CCGN | Start with 250 HP |

| A4ZT-AA22 | Buy anything at armor, weapon, and equipment shops no matter how much meseta you have |

| ALZT-AA7W | Items that you can afford are free |

| BXDA-AA5L | Fortune telling is free |

| BXAT-AA64 | Poison recovery at healer’s is free |

| BW9T-AA5E | Resurrection at the healer’s is free |

| A49A-AA28 | Technique distribution is free |

| REHT-C6VL | Using monomate, dimate, or trimate restores all lost HP |

| BTHA-CA9J | No TP lost for using Res technique |

| BTHA-CA38 | No TP lost for using Rever tech. |

| BTHA-CA6W | No TP lost for using Gires tech. |

| GCJT-B62W | No TP lost for using Anti tech. |

| CKBA-AA3G | One strike kills small front row enemies |

| B3FA-AA80 | One strike kills all large back row enemies |

| GTBT-CA3T | No HP lost in battle from enemy strikes |

| GTCT-CA5C | No HP lost in battle from enemy techniques |

| ATJT-CA50 | Characters cannot be poisoned |

| A2NT-AA8R | No enemies ever attack (This code must be turned off to complete the game) |

| CH1A-G0RG | Adds Orakio’s Sword to the items for sale in the Weapon Shop in Landen. |

| G11A-G0RG | Adds the Nei Claw to the items for sale in the Weapon Shop in Landen. |

| J91A-G0RG | Adds the Nei Shot to the items for sale in the Weapon Shop in Landen. |

| CS1A-G28C | Adds the Planar Armor to the items for sale in the Armor Shop in Landen. |

| JS1A-G0RG | Adds the Royal Helmet to the items for sale in the Armor Shop in Landen. |

| CS1A-G40C | Adds the Royal Knife to the items for sale in the Weapon Shop in Landen. |

| DM1A-G0RG | Adds the Royal Shield to the items for sale in the Armor Shop in Landen. |

| CS1A-HFGC | Adds the Pulse Cannon to the items for sale in the Weapon Shop in Landen. |

| GTFT-CA3T | Character In 1st Position Loses His Picture In The Status Screen |

| 9MTA-CCAN | Character In 4th Position Disappears From The World Map (He Or She Is Still There!) |

| GTFT-CALT | Character In 5th Position Loses His/Her Picture In The Status Screen |

| CCNA-GAZ2 | Foi technique works on all enemies (instead of just one). |

| NCAA-CCF4 | Get the Ceramic Knife (instead of the Knife) in the left chest in the Landen dungeon. |

| ECAA-CCF4 | Get the Nei Sword (instead of the Knife) in the left chest in the Landen dungeon. |

| YCAA-CAF4 | Get the Steel Sword (instead of the Knife) in the left chest in the Landen dungeon. |

| GTJT-CA3T | Gra And Maybe Zan Kill You Instantly |

| EJDT-CA8A | Makes any weapon attack all enemies on the screen |

| 98DT-GG58 | Makes the Nei Bow a one handed weapon |

| ACFT-GTCT | Makes the Nei Shot a one handed weapon |

| CCFT-GTHT | Makes the Nei Sword a one handed weapon |

| ACEA-GTFA | Max out all your stats after one battle. |

| ACBA-CBG6 | First chest has 0 meseta |

| NWBA-CBG6 | First chest has 100 meseta |

| 8WBA-CDG6 | First chest has 500 meseta |

| 7CBA-CHG6 | First chest has 1000 meseta |

| YCBA-C9G6 | First chest has 4000 meseta |

| BMTA-CCGN | Start with 10 hit points |

| CXTA-CCGN | Start with 20 hit points |

| GMTA-CCGN | Start with 50 hit points |

| NXTA-CCGN | Start with 100 hit points |

| 3DTA-CCGN | Start with 200 hit points |

| DDBT-AA5L | Inns are free |

| BTHA-CA91 | No technique points deducted using the Res tech |

| FFC03F:20 | No Random Attacks |

| FFC041:00FF | Mucho & Infinite Meseta |

| FFC0AE:03E7 | HP for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC0B2:03E7 | HP for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC0B0:03E7 | TP for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC0B4:03E7 | TP for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC0A4:FF | Speed for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC0B6:03E7 | Damage for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC0B8:03E7 | Defense for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC0D2:FF | Luck for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC0D3:FF | Skill for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC0AD:32 | Level 50 for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFDE82:0XXX | 1st Item Slot Modifier for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFDE84:0XXX | 2nd Item Modifier Slot for Rhys (centre position) |

| FFC1AE:03E7 | HP for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC1B2:03E7 | HP for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC1B0:03E7 | TP for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC1B4:03E7 | TP for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC1A4:FF | Speed for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC1B6:03E7 | Damage for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC1B8:03E7 | Defense for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC1D2:FF | Luck for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC1D3:FF | Skill for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC1AD:32 | Level 50 for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFDEC2:0XXX | 1st Item Modifier Slot for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFDEC4:0XXX | 2nd Item Modifier Slot for Wren (lower left position) |

| FFC12E:03E7 | HP for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC132:03E7 | HP for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC134:03E7 | TP for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC130:03E7 | TP for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC124:FF | Speed for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC136:03E7 | Damage for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC138:03E7 | Defense for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC152:FF | Luck for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC153:FF | Skill for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC12D:32 | Level 50 for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFDEA2:0XXX | 1st Item Modifier for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFDEA4:0XXX | 2nd Item Modifier Slot for Mieu (lower right position) |

| FFC2B2:03E7 | HP for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC2AE:03E7 | HP for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC2B4:03E7 | TP for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC2B0:03E7 | TP for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC2A4:FF | Speed for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC2B6:03E7 | Damage for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC2B8:03E7 | Defense for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC2D2:FF | Luck for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC2D3:FF | Skill for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC2AD:32 | Level 50 for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFDEE2:0XXX | 1st Item Modifier Slot for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFDEE4:0XXX | 2nd Item Modifier Slot for Sari (upper right position) |

| FFC22E:03E7 | HP for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFC232:03E7 | HP for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFC234:03E7 | TP for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFC230:03E7 | TP for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFC224:FF | Speed for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFC2B6:03E7 | Damage for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFC2B8:03E7 | Defense for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFC2D2:FF | Luck for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFC2D3:FF | Skill for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFC2AD:32 | Level 50 for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFDF02:0XXX | 1st Item Modifier Slot for Thea (upper left position) |

| FFDF04:0XXX | 2nd Item Modifier Slot for Thea (upper left position) |

Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom: A Divisive Dynasty

Introduction: The Black Sheep’s Ambition

Launched in 1990 for the Sega Genesis, Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom occupies a uniquely contentious space within one of gaming’s most revered RPG franchises. It is the black sheep, the aberrant entry, the game that dared to strip away the sci-fi chrome of its predecessors for a seemingly medieval fantasy veneer—only to reveal its true, galactic nature layers later. Its very subtitle, Generations of Doom, promises an epic, multi-generational saga, and on that count, it delivers a narrative ambition rarely seen in 16-bit RPGs. However, this ambition arrived shackled to a rushed development cycle, a team largely new to the RPG genre, and the immense pressure of following two landmark titles. This review will argue that Phantasy Star III is a profound study in squandered potential and revolutionary ideas. It is not a bad game, but it is a profoundly flawed one, where every brilliant, genre-expanding mechanic is counterbalanced by a significant, often glaring, presentation or design failing. Its legacy is not one of seamless continuity, but of fractured ambition—a fascinating “what if” that ultimately reshaped the series’ future by demonstrating both the power and peril of radical divergence.

Development History & Context: A New Team, A Rushed Vision

The development of Phantasy Star III is the first and most critical key to understanding its disparate nature. Following the completion of Phantasy Star II (1989), the core creative team—including series co-creator Yuji Naka and artist Rieko Kodama—immediately shifted to the monumental task of developing Sonic the Hedgehog (1991). This exodus left Sega with a vacancy for its flagship RPG series. A new team, composed largely of developers with little prior RPG experience, was assembled under director/writer Hiroto Saeki and co-director/writer Yasushi Watanabe (credited as S2 and Yang Watt, respectively). Veteran Rieko Kodama did contribute during the initial planning stages, offering guidance, but she was not part of the core development.

This team, driven by a desire to differentiate their product in a crowded market, made two seismic decisions. First, they would tell a story not directly tied to the Algo solar system’s planets (Palm, Motavia, Dezolis) but set on a seemingly isolated medieval world. Second, they would center the entire narrative on a “generation system,” where player choices in marriage would dictate the protagonist for the next chapter, leading to multiple endings. Producer Kazunari Tsukamoto later described the game as feeling like “a collection of side stories” compared to the connected narrative of PSII.

The technological constraints of the Sega Genesis cartridge format were severe. The team’s ambition to create a sprawling world with branching paths ran headfirst into storage limits. According to developer accounts, significant portions of the narrative and world-building had to be cut to realize the generation system’s scale. The game’s art director, Saru Miya, recalled the project as a difficult “home-spun” effort. Composer Izuho Takeuchi (credited as Ippo), barely two years into her tenure at Sega, found the project challenging due to her inexperience with RPG scoring and the tight schedule. The result was a game that feels both ambitiously scaled and visibly truncated, a draft of a grander vision that was perpetually on the verge of collapse.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Thousand Years of Misunderstanding

Phantasy Star III’s plot is a masterclass in delayed revelation, for better and worse. It begins not with a space cadet, but with a fairy-tale premise: Prince Rhys of Landen is to marry Maia, a mysterious amnesiac found on the shore. The ceremony is violently interrupted by a dragon, which kidnaps Maia, shouting, “Filthy Orakians, Maia will not be yours!” Thus begins a quest rooted in classic fantasy rescue tropes.

The genius of the narrative lies in its slow, painful unraveling of context. The “Orakians” and “Layans” have been in a cold war for 1,000 years, stemming from the disappearance of their founders, Orakio the swordsman and Laya the sorceress. The player, like Rhys, initially accepts this as a simple fantasy schism. The first twist is that Maia is a Layan princess, and her “kidnapping” was a rescue from the Orakians who had found her. The second, monumental twist—delivered roughly two-thirds through—reveals that this entire world is not a planet at all, but one of several biospheres within a colossal generation ship, a desperate ark fleeing the destruction of Palm from Phantasy Star II. The “medieval” societies are descendants of the Algo survivors who have forgotten their technological heritage, their history warped into myth. The final antagonist, Dark Force—the series’ recurring embodiment of chaos—is revealed to have been festering aboard the ship, subtly manipulating the Orakian/Layan conflict for millennia to feed on human strife.

Thematic Core: The game explores themes of cyclical conflict, the corruption of history into myth, and the nature of identity. The generation system itself is a thematic mechanic: the player’s choices literally shape the genetic and cultural inheritance of the next protagonist. Marrying a pure Orakian (Lena) produces a son (Nial) skilled only in swordsmanship. Marrying a pure Layan (Maia) produces a son (Ayn) proficient in “Techniques” (magic). Marrying a hybrid (Kara) produces a child with a mixed skill set. The story argues that our inherited biases (Orakian vs. Layan) are choices we can break, and that true progress requires synthesis, not purity. The ultimate revelation—that the entire war was an artificial construct—underscores the tragedy of needless division.

Narrative Structure & Pacing: The generational structure is the game’s defining feature. After Rhys’s first act, the player chooses a bride, leading to two distinct second-generation stories (Nial’s or Ayn’s). Each of those characters then faces a marriage choice, branching into four possible third-generation protagonists (Sean, Crys, Aron, or Adan). Each path has unique party members, quests, and a distinct final dungeon segment, culminating in four different endings. However, this structure comes at a severe cost: character development is brutally compressed. A protagonist like Ayn or Nial gets only 10-15 hours of focused play before the next generation begins, making it difficult to form a deep attachment. The game’s 30-40 hour length for a single run belies the fact that seeing all story branches requires 4-5 full playthroughs, a monumental task hampered by the game’s only two save slots.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Innovation Under Duress

The core Phantasy Star loop—top-down overworld exploration, random turn-based encounters, 2D dungeon crawling—is retained but significantly altered.

The Generation System: This is the undisputed star. It transforms the RPG from a linear journey into a branching family saga. The choice of bride is rarely based on deep narrative rapport (dialogue and personality are minimal) but on strategic considerations: desired character class (fighter vs. tech-user), potential party composition, and even aesthetic preferences like hair color. The system’s brilliance is in its tangible, mechanical consequences that ripple across generations. However, its implementation is lukewarm. The “branching” paths often reconverge on similar key items and locations, with the final act’s differences primarily confined to the first dungeon and the ending itself. The sense of playing an entirely different game is more promise than reality.

Combat System: A clear regression from PSII. The battle perspective shifts to a first-person view, showing only the enemy and the attacking weapon (a return to PSI’s style, losing PSII’s detailed character sprites). The interface is replaced with a clunky, large-icon menu system that, while innovative for its attempt at graphical commands, is slow and imprecise. The “Auto-Battle” macro system is a useful addition, allowing programming for one round or indefinitely. The “Technique Distribution” shops are a fascinating deep-cut mechanic: players can reallocate power points among a character’s four techniques within a category (Healing, Melee, Order, Time), allowing miniature customization. Yet, Techniques remain underutilized; basic weapon attacks are almost always more efficient, and the animations are simplistic and unimpactful.

Pacing & Grinding: A notable improvement over PSII. The level curve is forgiving, and random encounters provide sufficient XP to progress without excessive grinding. The pacing feels “just right” for a single generational playthrough. However, this benefit is nullified when starting a new generation, as the new protagonist begins at Level 1, forcing a brief, repetitive grind to catch up—a jarring reset that undermines the “legacy” feeling.

UI & Quality of Life: The two-save-slot limitation is a catastrophic design flaw for a game predicated on branching paths. It forces players to either sacrifice one branch or use external memory tools. The slow movement speed in towns and fields, often criticized, feels intentional to pad playtime but succeeds only in frustrating. The lack of meaningful NPC interaction—most townsfolk offer only single, inconsequential lines—contributes to a feeling of bland, empty worlds.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Study in Contrasts

Visual Presentation: PSIII is a game of two visual identities. Its strength lies in its larger, more detailed town and dungeon tilesets. Locations feel more architecturally defined than in PSII. Its catastrophic weakness is its color palette and monster design. The graphics are muted, brownish, and somber, losing the vibrant, sci-fi neon of its forebears. The monster designs are widely panned as inconsistent, ugly, and bizarre—ranging from abstract shapes to overly sexualized humanoids—with laughably poor animations (e.g., a dragon that attacks by wiggling its tongue while hovering motionlessly). The introduction of static battle backgrounds (a step forward from PSII’s black void) is appreciated but generic, lacking the environmental storytelling of PSI’s context-sensitive encounters.

Musical Achievement: In stark contrast to the visuals, the soundtrack is a high watermark for the series. Composer Izuho Takeuchi’s work is dynamic, emotionally resonant, and technically clever. The overworld theme is a masterclass in adaptive music: it is a simple, haunting two-voice motif when the party is alone. As each character joins, a new voice layer is added, creating a richer, more complex tapestry that symbolizes the growing fellowship. The battle music dynamically shifts between three tracks based on the fight’s tempo—”easy,” “balanced,” or “hard”—a subtle but effective pressure system. Tracks like “Dungeon,” “Wren Transforms,” and “Laya’s World” are atmospheric and memorable. The music nearly single-handedly carries the game’s emotional weight, especially in the voids left by the minimalist story presentation.

World Design & Atmosphere: The world initially presents as a generic high-fantasy landscape: continents named Landen, Aquatica, Draconia. The disconnect from the series’ space-opera roots is jarring. The genius is in the environmental storytelling that slowly contradicts this façade. Ruined airfields, maintenance tunnels connecting continents (revealed as spokes of a space station wheel), cyborgs, and laser weapons scattered in dungeons create a sense of profound, lost history. The revelation that the “world” is a generation ship is a breathtaking payoff, but the game does little to foreshadow it meaningfully. NPCs provide no lore, and the “caves” that connect regions are presented as mundane dungeons, not as artificial transit hubs. The atmosphere is one of lonely, melancholic exploration, bolstered by the sparse graphics and evocative music, but it lacks the cohesive worldliness of PSI or PSIV.

Reception & Legacy: The Scar That Shaped a Series

Phantasy Star III received generally positive reviews at launch (aggregating around 74%), particularly in European and French magazines (Consoles Plus, Player One) that praised its generational gimmick and epic scope. Electronic Gaming Monthly called it an improvement over its predecessors. However, even contemporary reviews noted its high price and uneven presentation.

Retrospective reception is starkly polarized and has defined its legacy. It is almost universally labeled the “black sheep” of the original Phantasy Star quadrilogy. Critics and fans consistently cite:

1. Aesthetic Dissonance: The drastic shift in art style and color palette felt like a betrayal of the series’ identity.

2. Narrative Disconnection: Its initial refusal to engage with the Algo system and PSII’s cliffhanger (Palma’s destruction) felt like a side story masquerading as a sequel.

3. Technical Shortcomings: Poor monster animations, simplistic dungeons, and a clumsy battle interface.

4. Underdeveloped Ambition: The generational system’s potential felt truncated, with insufficient time to invest in each character and a story that required multiple full playthroughs to comprehend.

This backlash had a direct, profound impact on the series’ future. The development of Phantasy Star IV: The End of the Millennium (1993) was explicitly a course correction. The original team returned, and PSIV was designed as a direct, loving sequel to PSI and PSII, cramming in references and callbacks to soothe fans. In a perverse twist, PSIII’s legacy is that it made PSIV feel more insular and continuity-obsessed. It also demonstrated the commercial and critical risk of such a radical departure.

Its Influences: Despite its flaws, PSIII’s generational branching was years ahead of its time. It predates and arguably influenced later narrative-heavy RPGs like Chrono Trigger (multiple endings, character-specific stories) and the Suikoden series (inheritance, political legacy). Its core idea—that player choices can alter not just the story but the very nature of the protagonist across decades—remains a tantalizing, rarely-executed design goal in RPGs.

Conclusion: A Flawed Heir to a Legend

Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom is an essential, deeply conflicted artifact of RPG history. It is not the equal of Phantasy Star I, II, or IV* in terms of polish, cohesion, or sheer enjoyability. Its presentation is often ugly, its pacing uneven, and its world-building obtuse. The rushed development is evident in every cartridge’s seams.

Yet, to dismiss it as merely the “bad” Phantasy Star is to miss its monumental contributions. Its generational saga was a quantum leap in interactive storytelling, introducing concepts of legacy, inheritance, and consequence that stretched the definition of a single-game narrative. Its music is among the best on the Genesis. And its ultimate thematic payoff—the revelation of the generation ship and the manufactured nature of the conflict—is a brilliant, series-unifying twist that retroactively justifies its oddness.

Its place in history is secure, not as a pinnacle, but as a cautionary masterpiece. It proves that revolutionary ideas can be choked by practical constraints and that fan loyalty is fragile. It is the game that taught Sega the value of consistency, but also hinted at narrative possibilities they would only fully explore years later. To play Phantasy Star III today is to engage with a fascinating, broken thing: a royal lineage born in a development crunch, whose fragmented story of Orakio and Laya finally finds its true context not within its own world, but in the shadow it cast over the triumphant Phantasy Star IV that followed. It is a game worth playing once, for its ambition alone, even as you mourn what might have been.

Final Verdict: 7/10 – A Fascinating Failure. Ambitious, innovative, and structurally impressive, but fatally undermined by rushed execution, poor presentation, and design choices that actively work against its own brilliant core concept. The black sheep of the series, but a crucial one.