- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Cyberium Multi Media B.V.

- Developer: Arena Games, Eclipt Design, ET Audiocom

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Pinball

- Setting: Air Combat, Ocean, Space, Underworld

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

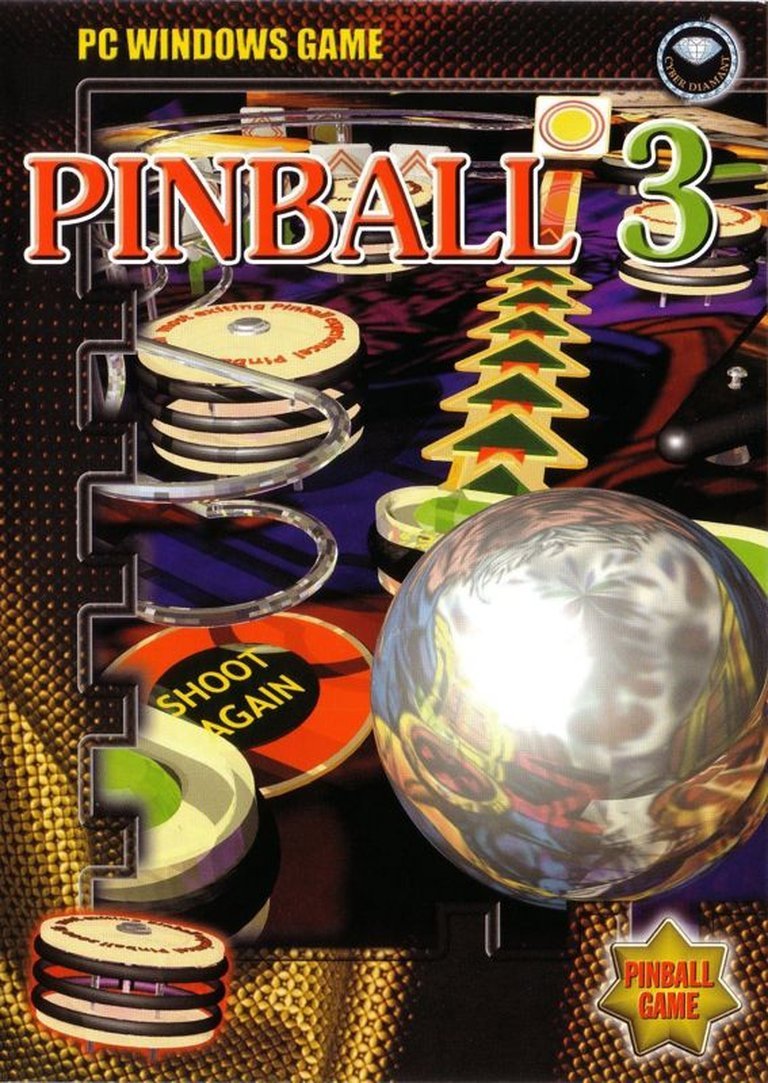

Pinball 3 is a 2001 Windows remake of Cyberball, offering four distinct pinball tables: Dooke (underworld devils theme), Enlightment (space travel), Air Crash (modern air combat), and Shark Attack (treasure hidden in the sea guarded by sharks). The game innovates with square playfields containing multiple areas, and screen resolution affects scrolling—from the ‘cyberview’ mode (320×240) with up-down scrolling to ‘full view’ (1024×768) showing everything—along with options like player count and physics adjustments.

Pinball 3 Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (80/100): Bethesda Pinball is a solid download for Pinball FX3 and fans of these games should get this pack right away.

Pinball 3: A Forgotten Frontier in Digital Pinball’s Early 21st Century Landscape

Introduction: The Obscure Remake

In the vast and storied history of video game pinball, a handful of titans—Pinball Dreams, Full Tilt! Pinball, the Williams/Bally tables—dominate the conversation. Yet, nestled in the shadow of these giants, often overlooked and rarely discussed, lies Pinball 3 (2001). This Windows-only release from the Dutch studio Arena Games, published by Cyberium Multi Media B.V., represents a curious and technically ambitious footnote in the genre’s evolution. It is not a licensed simulation of famous real-world tables, nor a flashy arcade-style adrenalizer. Instead, it is a direct, if obscure, remake of the 1989 arcade game Cyberball, reimagined through the lens of digital pinball. My thesis is this: Pinball 3 is a fascinating artifact of transitional technology and niche design, a game that daringly experimented with spatial mechanics and player customization in an era increasingly dominated by photorealistic physics simulations and intellectual property tie-ins. Its obscurity is not a measure of its worth, but a symptom of its divergence from the mainstream path of digital pinball.

Development History & Context: The Last Gasp of a Niche Genre

The development context for Pinball 3 is as obscure as the game itself. The credits list three entities: Arena Games as the primary developer, with Eclipt Design and ET Audiocom handling likely art/design and sound duties, respectively. This suggests a small, specialized European team rather than a major studio. The publisher, Cyberium Multi Media B.V., was a Dutch company known for budget and compilation titles, which immediately frames Pinball 3 within a commercial context of affordability and accessibility over blockbuster ambition.

The year 2001 was a pivotal, yet uncertain, time for PC pinball. The “Golden Age” of arcade pinball machines (1970s-1990s) had officially ended with Williams’ shutdown of its pinball division in 1999, as chronicled in the history from the Strong Museum of Play. The video game market was shifting towards 3D accelerators and online play. For digital pinball, this was a period of quiet innovation and consolidation. Zen Studios’ foundational work was years away, and the market was populated by relics like 3-D Ultra Pinball (1995) and Full Tilt! Pinball (1995), which were already aging. Pinball 3’s release feels less like a product of a booming genre and more like a dedicated team finishing a specific project—a remake of Cyberball—amidst a changing technological tide.

Technologically, the game’s defining feature is its resolution-dependent scrolling system. The “cyberview” mode (320×240) forces the playfield to scroll vertically, revealing a square table piece by piece, while the “full view” (1024×768) displays the entire multi-area square playfield at once. This was a pragmatic solution for lower-end PCs of the era, allowing the game to run on modest hardware by only rendering a portion of the playfield. It speaks to an era of significant hardware disparity, where developers had to build scalability into the core visual experience. The option to “tamper with game physics” further indicates a focus on the hardcore simulationist crowd, a niche that existed even then but was shrinking.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absence of Story

Here, the source material provides a crucial, revealing piece of information: there is no narrative, no characters, no dialogue, and no underlying themes in a traditional sense. Pinball 3 is a pure, unadulterated mechanical simulation. Its four tables—Dooke (underworld devils), Enlightenment (space travel), Air Crash (modern air combat), and Shark Attack (treasure guarded by sharks)—are not storytelling environments but thematic skins. They provide a visual and auditory aesthetic (implied by their names) that overlays the identical square-playfield mechanics.

This is a stark contrast to the narrative ambitions of the arcade machines it remakes, and to contemporary pinball games that often featured elaborate lore through backglass art and DMD animations. The Cyberball arcade game itself was a futuristic sport, a narrative in its own right. Pinball 3 strips this away to its bare geometry. The “themes” exist solely as a collection of visual motifs—likely sprites for bumpers, targets, and the playfield itself—and corresponding sound effects (ET Audiocom’s contribution). There is no “quest” in Shark Attack beyond hitting targets; no “story” in Enlightenment beyond shooting at space-themed objects. This absence is its own thematic statement: pinball as an abstract, mechanical sport. The ball’s interaction with the square, multi-zone playfield is the experience. The themes are purely decorative, a choice that would feel increasingly archaic as the 2000s progressed and games like The Pinball Arcade or Pinball FX obsessively replicated the licensed narratives and artwork of real machines.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Geometry and Scrolling

The heart of Pinball 3 is its radical departure from the standard rectangular playfield. The source explicitly states: “Unlike other games, where tables follow a common rectangular playfield, in Pinball 3 they are square with two or more areas.” This is its single most defining and innovative mechanic. These aren’t traditional tables; they are zones connected within a square matrix. A shot might send the ball from an “upper-left” zone to a “lower-right” zone via a ramp or chute, creating a non-linear, architectural pinball experience. This design philosophy aligns more with experimental titles like Obsession (1997) or Total Pinball 3D than with Williams or Bally designs.

The resolution-scrolling mechanic is inextricably linked to this geometry. In 320×240, the player sees only a window into the full square playfield. Navigating requires mental mapping of how zones connect, with the ball disappearing off-screen only to reappear elsewhere. This introduces a layer of spatial anticipation missing from fully visible tables. In 1024×768, the entire strategic layout is laid bare, shifting the challenge from navigation to pure shot execution and resource management across zones. This is a brilliant, if divisive, design choice that fundamentally alters the cognitive load of playing.

The core gameplay loops are classic pinball: launch ball, keep it in play with flippers, hit targets to score points and light features, aim for multi-ball and jackpot shots. However, the implementation is barebones by modern standards. There is no sophisticated rule set with modes, lane saves, or complex stacking. It is, at its core, a test ofControl on a novel geometric plane. The character progression is nonexistent beyond a persistent high score table. The UI is functional, likely displaying the current score, ball count, and maybe a simple zone indicator. The “tamper with game physics” option is a raw developer-like tool, allowing players to adjust gravity or ball speed, which speaks to the game’s dual identity as both a consumer product and a sandbox for enthusiasts.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of the Abstract

Given the lack of narrative, world-building is entirely environmental and auditory. Each of the four tables creates its atmosphere through a cohesive, if simple, visual package:

* Dooke: Presumably uses a palette of reds, blacks, and fiery oranges, with demonic skulls or hellish imagery on bumpers and targets.

* Enlightenment: Blues, purples, stars, and planetary motifs, evoking a sterile, futuristic space.

* Air Crash: Grays, military greens, and jet fighter silhouettes, focusing on a theme of modern aerial conflict.

* Shark Attack: Deep blues, aquatic greens, treasure chests, and, of course, shark sprites.

These are early-2000s DirectDraw-era graphics—2D sprites and hand-drawn (or simple software-rendered) playfields. They lack the lighting effects, reflective metals, and detailed animations of the late-90s Williams solid-state machines or the 3D rendering of later sims. The art direction is functional and thematic, aiming for immediate recognition rather than immersion.

Sound design by ET Audiocom follows suit. Each table likely has a distinct set of sampled sound effects: synthesized explosions for Air Crash, bubbling noises for Shark Attack, perhaps ominous choir pads for Dooke, and electronic tones for Enlightenment. The music, if present at all, would be low-bitrate MIDI or simple looped audio tracks, a common cost-saving measure in budget PC titles of the time. The soundscape’s primary function is feedback—confirming hits and providing basic atmosphere—not storytelling. Together, the art and sound create a “feel” for each zone, but they serve the geometry-first gameplay, not a narrative second.

Reception & Legacy: The Sound of Silence

The official reception data is tragically sparse. On MobyGames, Pinball 3 has a Moby Score of “n/a” and a player average of 3.0 out of 5, based on a single rating from one collector. There are zero critic reviews and zero player reviews submitted. This is the clearest indicator of its commercial and cultural failure. It was a game that existed in the catalog, was purchased by a tiny handful of enthusiasts (six collectors on MobyGames), and then vanished without a trace. It made no impact on contemporary gaming magazines or websites.

Its legacy is therefore one of obscurity and niche curiosity. It did not influence the mainstream direction of digital pinball. The industry moved towards:

1. Faithful Simulations: The Pinball Hall of Fame series (2004+) and The Pinball Arcade (2012+) focused on exacting recreations of historic machines, leveraging nostalgia and licensing.

2. Modern Physics & 3D: Pinball FX (2007) and its sequels emphasized glossy 3D graphics, realistic ball physics, and regular new table releases.

3. The Niche Experimental Titles: A few games continued to play with form, like Yoku’s Island Express (2018) with its metroidvania pinball hybrid, but the square, scrolling multi-zone table was not a path others followed.

Pinball 3’s legacy is as a what-if. It demonstrated that the fundamental pinball experience could be rethought around geometry and visibility rather than replication. Its scrolling mechanic is a fascinating solution to a spatial puzzle that most designers simply avoided by making wider playfields. It is a testament to the fact that the early 2000s PC indie scene (even within a publisher’s banner) could still produce idiosyncratic, mechanically-focused games that prioritized novel interaction over polish or franchise power. It is a dead-end branch on the evolutionary tree, but one with an intriguing mutation.

Conclusion: A Curious Artifact of Design Purism

Pinball 3 is not a “good” game by any conventional critical metric. It is visually dated, lacks content, was commercially stillborn, and exists in a historical vacuum. However, to dismiss it is to miss its profound, if flawed, design purity. It is a game that asked, “What if the pinball playfield was a square of discrete zones, and seeing all of it was a player option?” and then built an entire product around that single, radical question. In an era increasingly defined by content volume, IP synergy, and graphical spectacle, Pinball 3 is a relic of a different mindset: one where a small team could experiment with the spatial core of a genre, unburdened by the need for stories, licenses, or online leaderboards.

Its place in history is secure as a curio and a case study in mechanical divergence. It represents the final gasp of a certain kind ofPC-focused, abstract pinball design before the genre was largely consolidated under the banners of simulation and licensed spectacle. For the historian, it is invaluable evidence of an alternate path not taken. For the player, it is a curious, challenging, and ultimately obscure experience that rewards those willing to grapple with its unique geometry and forgiving, physics-tamperable nature. Pinball 3 did not change the world, but in its own quiet, forgotten way, it proved that even the most established game formulas still have unexplored rooms—if you’re willing to scroll sideways to find them.