- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Media Contact LLC

- Developer: Media Contact LLC

- Genre: Action, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Real-time, Upgrades

- Setting: Caribbean

Description

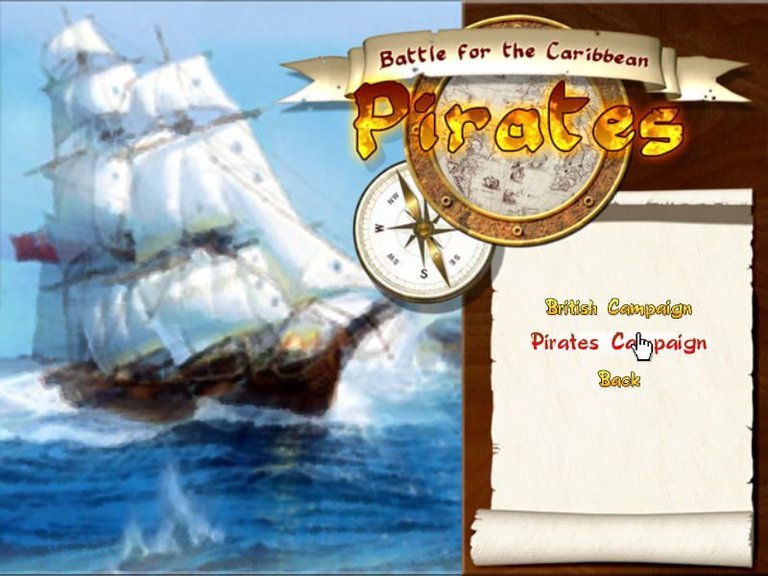

Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean is an action-strategy game set in the Caribbean where players defend their island fortress from waves of enemy pirate ships. Using mouse controls, players fire cannons to destroy ships, earn booty for upgrades like faster cannons, minefields, or a patrol shark, and face increasingly powerful enemies across two campaigns and a survival mode that emphasizes hectic, addictive gameplay.

Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean Reviews & Reception

honestgamers.com : Entertaining? Definitely.

Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean: A Review of a Forgotten Freeware Fortress Defense

Introduction: A Ghost Ship on the Digital Horizon

In the vast, churning ocean of video game history, certain titles exist as spectral vessels—visible on radar but fading into the mist upon closer inspection. Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean, released on February 15, 2007, by the enigmatic Media Contact LLC, is one such ghost ship. This freeware Windows title, a top-down, real-time arcade action-strategy hybrid, represents a fascinating footnote: a game that leveraged the explosive popularity of the Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise yet stands entirely apart from it, unlicensed and unconnected. Its legacy is not one of blockbuster sales or critical acclaim, but of obscurity, with a single recorded critic score of 75% and a mere handful of collectors on databases like MobyGames. This review will argue that Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean is a compelling case study in minimalist game design, a pure distillation of the “one more wave” gameplay loop that captures the frantic, click-happy spirit of early 2000s casual PC gaming, even as it remains umbilically linked to a franchise it does not officially belong to.

Development History & Context: The Anonymous Studio and the Freeware Sea

The studio behind Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean, Media Contact LLC, is a phantom. No credits beyond the publisher/developer name exist in available records, and the company leaves no discernible footprint in industry archives. This anonymity places the game firmly in the long tradition of small-scale, often single-person, European or North American freeware/shareware projects of the late 1990s and 2000s—a world of AOL-hosted .zip files, personal websites, and exposure through portals like CNET’s Download.com or, in this case, preservation sites like My Abandonware.

The technological context of 2007 is key. This was a period of transition: the rise of digital distribution (Steam was growing, but not dominant), the persistence of casual web-based and downloadable games, and the twilight of the simple, mouse-driven arcade experience on PC. The game’s engine is not specified, but its requirements—a top-down 2D perspective, simple sprite-based ships and particle effects for explosions, and a UI driven entirely by mouse input—suggest a lightweight, likely self-developed engine or a very basic commercial package (like Clickteam Fusion or similar). The business model was pure freeware: no ads, no microtransactions, just a downloadable 11 MB setup file. This was a hobbyist project, or at best a low-budget commercial attempt to capture a fleeting trend.

Crucially, it was released in the same year as Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End film and its official, multi-platform video game. The Wikipedia list of franchise games shows a crowded field in 2007: official titles from Disney Interactive, Eurocom, and others spanned MMOs, console action-adventures, and mobile games. Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean was an unlicensed interloper, a piece of “cognitive surplus” (to borrow Clay Shirky’s term) from a developer banking on the public domain association of “pirates” and “Caribbean,” untethered from Disney’s intellectual property. It is a game born not from a licensing deal, but from a thematic impulse.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Code is Silence

In stark contrast to the sprawling, character-driven sagas of the Disney films, Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean offers a narrative vacuum. There is no story, no characters, no dialogue, and no overarching plot. The two “campaigns” are simply templated difficulty or thematic variants: one where the player defends a fort against navy ships (implying you are the pirates), and another against pirate ships (implying you are the navy). The lore, such as it is, is conveyed entirely through the setting and mechanics: you are a lone gun emplacement on a small Caribbean island, and you must repel endless seaborne assailants.

This absence is its own thematic statement. The game strips piracy down to its most basic, violent arithmetic: ships approach, you destroy them, you earn money, you fortify, and you repeat. It aligns not with the romantic, supernatural adventure of Jack Sparrow, but with the grim, relentless toll of coastal defense. There is no treasure to hoard, no code to uphold, no parley to call—only survival. The “white shark” upgrade mentioned in the MobyGames description is the closest the game comes to introducing a character, but it functions as a simple automated turret, a piece of equipment with no personality. The theme is not Pirates of the Caribbean; it is Defense of the Outpost, with a piratical coat of paint.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Zen of the Click

The core loop is brutally simple, as articulated in the HonestGamers review: “You aim the shots by clicking where you want the cannon to shoot, you hit the ships by clicking where they’re going to be, not where they are.” This is the essence of the game: a top-down, 2D aiming mechanic requiring predictive skill. The player controls a single fortified island in the center of the screen. Enemy ships enter from the edges and steam toward the fort in straight or slightly curved lines. The left mouse button fires the main cannon; a second, faster-firing smaller cannon may be available depending on upgrades.

Combat & Resource Economy: Destroying a ship yields a specific amount of “booty” (money). This currency is spent between waves on an upgrade tree. The MobyGames description lists the options: “faster or more accurate cannons to mine fields or a white shark.” The HonestGamers review expands slightly, mentioning “mines,” “increasing defense,” and “adding another cannon.” This creates the primary strategic layer: risk assessment. Do you spend on immediate damage output (more/faster cannons) or area denial/defense (mines, the shark)? Do you upgrade the fort’s hit points to survive longer barrages? The economy is straightforward and punitive—failure means lost income, creating a classic difficulty snowball.

Game Modes: The two campaigns are essentially preset upgrade paths or enemy types within a progressive wave system. The true test is the Survival Mode, described as starting with “a huge amount of booty.” This is the game’s purest form: an endless, escalating siege where the player’s initial choices create a unique build for a marathon of chaos. The “overwhelming” feeling noted by HonestGamers is the design goal—a desperate, chaotic clicking frenzy where screen-filling explosions are the norm.

Innovation & Flaws: The innovation lies not in complexity but in purity. It’s a “turret defense” game before the genre was formally codified, predating the boom of Flash tower defense games. Its flaw is its absolute simplicity. There is no meta-progression (permanent unlocks), no branching paths, no story. The “innovative” white shark is a minor novelty. The game is a skill tester with a shallow, but satisfying, upgrade branch. The aiming mechanic is its heart and its limitation—it offers depth through prediction but no variety in weapon types or enemy behaviors beyond speed and health increases.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Caribbean by Default

The setting is the Caribbean, as per the MobyGames “Groups” tag, but this is suggested purely by the blue water backdrop, the shape of the ships (likely generic galleons), and the pirate-themed title. There is no artistic identity. The visual direction is functional 2D sprite work. Ships are simple pixel or vector shapes; the fort is a basic structure; explosions are standard particle effects. The atmosphere is purely functional—a clean, readable top-down view where the color-coding of ships (if any) might indicate type, but the sources provide no such detail.

Sound design, if present at all, is not mentioned in any source. Given the 11 MB file size and era, it likely consisted of simple, looping .wav files: a cannon blast, a wooden ship crunch, perhaps a generic shanty melody. It would be entirely atmospheric and disposable, serving only to punctuate the clicking.

The entire aesthetic is one of “good enough.” It communicates the setting just sufficiently to justify the mechanics, with zero ambition to immerse the player in a world. This is not a criticism but an observation of its niche: a quick, free stress-relief toy, not an immersive simulator.

Reception & Legacy: The 75% Enigma

Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean exists in a critical void. The sole recorded critic review, from the Dutch/Belgian magazine Gameplay (Benelux), awarded it 75%. The review’s Dutch descriptor, “Hectisch, maar bijzonder verslavend” (” Hectic, but particularly addictive”), perfectly distills the HonestGamers take: “Hectisch” (hectic/chaotic) and “verslavend” (addictive) are two sides of the same coin—the frantic, repetitive, rewarding gameplay loop.

Commercially, as freeware, its “sales” are downloads. It has been collected by only 3-5 users on MobyGames, a stark number that speaks to its obscurity. It was once available on platforms like My Abandonware, cementing its status as abandonware—a piece of software whose original owner has likely discontinued support, now preserved only by enthusiasts.

Its legacy is bifurcated:

1. As a Pirates Game: It is a non-entity. The exhaustive Wikipedia list of Pirates of the Caribbean video games does not include it, correctly, as it has no franchise affiliation. It is a thematic parasite, capitalizing on a popular phrase without contributing to the canon.

2. As a Game Design Artifact: It is a clear precursor to the modern “clicker” and hyper-casual defense genres. Its simplicity foreshadows the的成功 of games like Fieldrunners or even the Kingdom Rush series in terms of core defensive positioning and resource economy, though without the tower variety or charm. It represents the raw, unpolished id of the casual PC gaming market—a market that would soon be dominated by portals like Big Fish Games and later, mobile app stores.

Its influence is indirect and diffuse. It did not shape major studios or franchises. Instead, it is a fossil of a specific moment: when a competent, focused arcade game could be made and distributed for free by an unknown team, find a tiny audience, and then quietly sink into the digital sediment.

Conclusion: A Perfectly Serviceable Curio

Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean is not a lost masterpiece. It is not a hidden gem that “time forgot.” It is, by all available evidence, a perfectly competent, exceedingly simple, and completely average piece of freeware from 2007. Its thesis is not profound; it is the immediate, tactile pleasure of aiming and clicking, of watching sprites explode, and of optimizing a small system against relentless waves. The 75% score from Gameplay (Benelux) is likely accurate—it excels at what it sets out to do within its tiny scope, but that scope is limited to a few hours of entertainment before repetition sets in.

Its true value for the historian lies in its context. It is a data point in the genealogy of the “tower defense” and “clicker” genres. It is evidence of the chaotic, IP-agnostic landscape of pre-App Store casual PC gaming. And it serves as a silent rebuke to the bloated, franchise-driven game industry of its time and ours—proof that a game with no story, no characters, no multiplayer, and no license could still offer a tight, addictive, and memorable (if shallow) experience. It will not rock your soul, as HonestGamers noted, but for those who remember the era of downloading obscure .zip files for a 30-minute diversion, Pirates: Battle for the Caribbean is a perfectly adequate son of the Caribbean, a ghostly echo of a simpler, click-driven time.

Final Verdict: 6/10 – A historically interesting artifact of freeware game design. Functionally addictive but artistically void. Worth a single, hefic, click-filled playthrough for preservationists and students of casual game evolution, but offering little to anyone else. Its place in history is not on a pedestal, but in a glass case labeled “Typical Example, Circa 2007.”