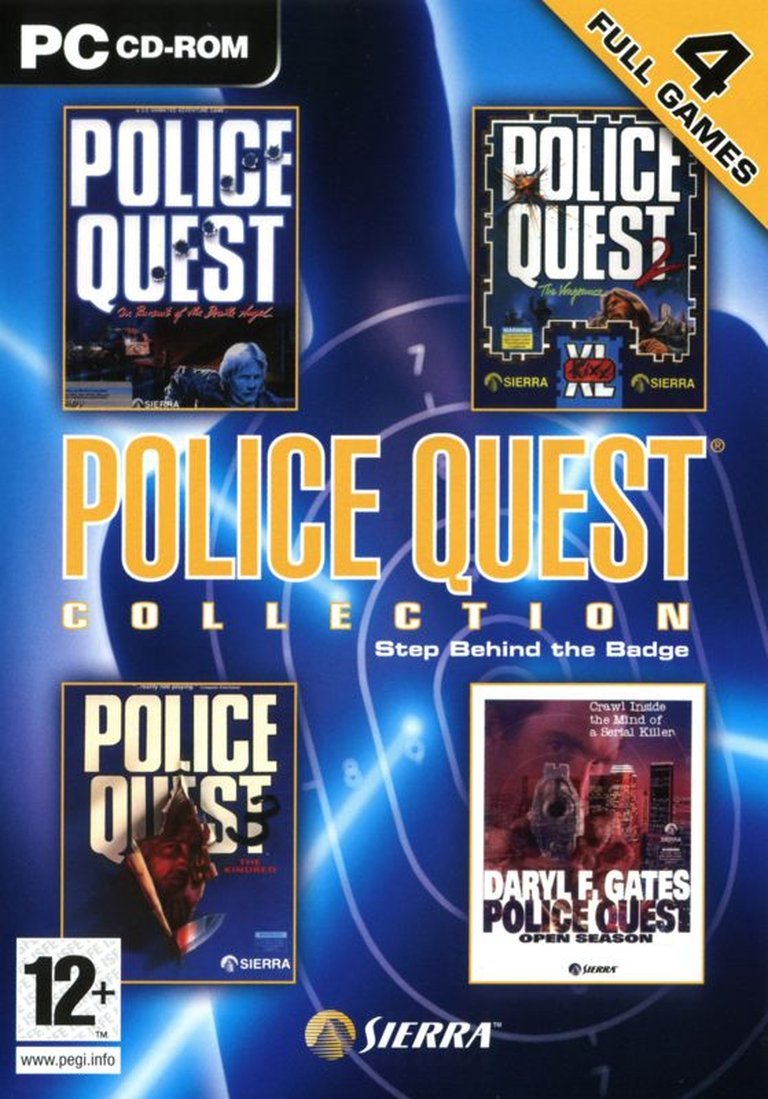

- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Activision Publishing, Inc., Sierra Entertainment, Inc.

- Developer: Sierra On-Line, Inc.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Setting: Law enforcement

- Average Score: 90/100

Description

Police Quest Collection is a compilation of the first four games in Sierra On-Line’s classic adventure series, immersing players in the role of a police officer tasked with solving crimes through procedurally accurate investigations and detective work. Set in gritty, realistic urban environments from the late 1980s and early 1990s, these games emphasize authentic law enforcement protocols and narrative-driven mysteries, offering a nostalgic yet educational glimpse into police simulation.

Where to Buy Police Quest Collection

Police Quest Collection Free Download

Police Quest Collection Guides & Walkthroughs

Police Quest Collection Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (90/100): The Police Quest series is an extremely underrated part of the classic Sierra canon of adventure games.

Police Quest Collection: Step Behind the Badge – A Definitive Historical Analysis

Introduction: The Thin Blue Line of Gaming History

To understand the Police Quest Collection is to understand a pivotal, though often overlooked, chapter in the evolution of the narrative adventure game and the police procedural genre in interactive media. Released in its most recognized form in 2006 by Vivendi Games, this compilation does more than simply bundle four classic titles; it serves as a time capsule of Sierra On-Line’s ambitious and technically daring late-’80s to mid-’90s era. The series, conceived by a former police officer and later shepherded by a real-life police chief, distinguished itself from contemporaries like King’s Quest or Leisure Suit Larry by enforcing a brutal, unforgiving adherence to real-world law enforcement procedure. Your pixelated life, and the fate of the case, depended on it. This collection’s thesis is two-fold: it represents the zenith of Sierra’sparser-and-point-and-click adventure hybrid design with a hyper-specific thematic focus, and it chronicles a creative and tonal shift that mirrors the changing landscape of both game development and the public perception of policing itself. It is a flawed, uneven, but profoundly influential artifact.

Development History & Context: From patrol car to pixelated crime scene

The genesis of Police Quest lies in the unique partnership between Sierra On-Line, the dominant force in PC adventure gaming, and Jim Walls, a retired California Highway Patrol officer. Walls’ firsthand experience provided an unprecedented level of procedural authenticity that was baked into the very design of the first three games. As he noted in later interviews, the fan mail from kids aspiring to be cops confirmed they were on the right track, highlighting the series’ accidental edutainment quality. The first game, In Pursuit of the Death Angel (1987), was built on Sierra’s AGI engine—the same used for King’s Quest—resulting in a hybrid of text parser commands and a top-down, navigable city map for driving sequences. This created a hybrid “open world” feel rare for its time.

The technological constraints were significant. EGA graphics (16 colors) defined the early entries, limiting visual fidelity but forcing creative environmental storytelling. The shift to Sierra’s Creative Interpreter (SCI) engine with Police Quest II (1988) and the full mouse-driven SCI1 for Police Quest III (1991) reflected the industry’s move away from text parsers toward point-and-click interfaces. Police Quest III also marked a turning point in development; Walls left Sierra during its production, with Jane Jensen (future creator of Gabriel Knight) finishing the dialogue. His departure and the subsequent hiring of former LAPD Chief Daryl F. Gates for Police Quest: Open Season (1993) signaled a fundamental creative and philosophical shift. Gates’ tenure, utilizing the more advanced SCI2 engine with digitized photographic backgrounds and live-action sprites, traded the “by-the-book” simulation for a darker, more cinematically sensational experience. This 2006 collection, titled Step Behind the Badge, primarily collects the first four games, including the VGA remake of PQ1 but omitting its original AGI version, and uses DOSBox emulation for Windows XP compatibility—a crucial preservation effort for a format rapidly being lost to time.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Ballad of Sonny Bonds and the Fall of Lytton

The narrative arc of the first three games is a tightly wound, character-driven saga centered on Sonny Bonds. In In Pursuit of the Death Angel, Bonds is a 15-year veteran patrolman in the fictional, rapidly decaying town of Lytton, California. A seemingly simple car crash investigation unravels a homicide linked to the vicious drug lord Jessie Bains, “The Death Angel.” The story’s emotional core is Bonds’ reunion with his high school sweetheart, Marie, now working as a prostitute (“Sweet Cheeks”). The narrative is procedural, methodical, and grounded. Police Quest II: The Vengeance escalates the personal stakes: after Bains’ imprisonment, he escapes, executing a campaign of revenge against all involved. Bonds, now a homicide detective, must protect Marie. The theme of “It’s Personal” becomes explicit, though the game still demands cold, procedural responses to threats. The emotional payoff—Bonds saving Marie and proposing—is hard-earned.

Police Quest III: The Kindred delves into domestic horror. Married to Marie, Bonds now faces a city overrun by a drug cartel and a satanic cult. The personal trauma hits its peak when Marie is stabbed and left in a coma. The narrative powerfully explores Bonds’ rage and fear, a stark departure from the cool professionalism of earlier entries. The villains shift from the singular evil of Bains to a more diffuse criminal ecology, including the Bains family and a corrupt cop, Pat Morales. The theme of “Surprisingly Realistic Outcome” manifests when Marie’s recovery is slow and imperfect, and the final confrontation is less a climactic shootout and more a tense, procedural takedown. The “Chekhov’s Gun” of the tracking device from earlier becomes vital.

With Open Season, the narrative and thematic foundation shifts catastrophically. The Sonny Bonds era ends. We are now John Carey, an LAPD detective in Los Angeles, investigating the murder of his partner. The game embraces a “Darker and Edgier” aesthetic, tackling hate crimes, neo-Nazism, graphic child murder, and mutilation with a sensationalist, true-crime TVShow lens. The intricate, personal Bains saga is abandoned for a series of lurid, largely disconnected vignettes (the Bobby Washington case, the supremacist couple) that serve as red herrings. The focus on meticulous police procedure evaporates, replaced by a desire to shock. Carey’s personal connection is thin compared to Bonds’. This is not a sequel in spirit but a rebranding, leveraging Daryl Gates’ name for credibility while pursuing a more cinematically violent, less intellectually rigorous vision. The emotional through-line is severed, marking the point where the franchise began its transition away from adventure and toward the tactical shooter genre of the later SWAT games.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Tyranny of Procedure

The gameplay of the Police Quest series is its defining, most polarizing feature: a relentless demand for by-the-book cop behavior. This is not a power fantasy; it is a simulation of responsibility, where “Video Game Cruelty Punishment” and “Violation of Common Sense” are immediate game-overs. The first game, in its original AGI form, required precise text commands (e.g., “get keys,” “open door”). The 1992 VGA remake, included here, modernizes this to a point-and-click interface but retains the parser-like logic in its verb-noun interaction system. The iconic top-down driving segments are a unique feature, requiring the player to obey traffic laws, use turn signals, and properly secure the vehicle—failure to inspect the squad car for a flat tire is an infamous “Unintentionally Unwinnable” scenario.

The scoring system is a masterclass in Sierra’s design philosophy. Points are awarded for proper procedure: making a traffic stop correctly, using the right amount of force, securing evidence, reading Miranda rights. You lose points for errors. This creates a compulsive drive for 100% completion, rewarding deep engagement with the included manuals, which doubled as copy protection and contained vital procedural references, poker rules, and radio codes. The manual was not just lore; it was the key to survival.

Police Quest II introduced a more linear, over-the-shoulder driving view and made firearm maintenance a critical, deadly serious mechanic. Forgetting to clean your gun would cause a misfire at a crucial moment. Police Quest III returned to the top-down map but with a mouse-driven interface that many found frustratingly non-intuitive for navigation, though it deepened investigative tools. The game also introduced complex partner dynamics and more subtle evidence gathering.

Open Season jettisoned almost all of this. Driving is minimal. The interface is simpler, focused on examining crime scenes and using a limited inventory of forensic tools (e.g., luminol, a putty knife). The puzzles are less about procedure and more about finding the next trigger for the next FMV sequence. The “Guide Dang It!” moments are abundant, often requiring obscure actions with no in-game hint, making the included manuals even more critical. The core loop becomes “explore, find evidence, trigger cutscene,” a significant simplification that many fans found unsatisfying.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Grittier, Grittier Streets of Lytton and LA

The world of Police Quest is a character in itself. Lytton, California, is a fictional stand-in for any mid-sized American city besieged by the crack epidemic and urban decay of the late ’80s. Its aesthetic is defined by EGA and VGA palettes: grimy alleyways, flickering neon signs, sterile police stations, and bland suburban homes. The “Wretched Hive” feeling is palpable. The world feels lived-in through its environmental details—newspaper clippings on bulletin boards, the hum of police radios, the ever-present threat of jaywalkers getting hit by cars (“Drives Like Crazy”). The series is famous for its “Hide Your Children” trope; children are almost entirely absent from Lytton, a deliberate design choice explained in the PQ3 VGA manual as a protective city program, which only heightens the atmosphere of urban menace.

The art direction evolves dramatically. PQ1 (VGA) and II use detailed, hand-drawn pixel art with a distinct, almost “Art Shift” into a Buddy Cop Show aesthetic. PQ3 employs richer VGA colours and more animated sprites, with a grittier, more mature visual tone reflecting its darker story. Open Season represents the pinnacle of Sierra’s pre-3D digitized sprite technology. Using scanned photographs for backgrounds and filmed actors for characters, it aims for a grim, photorealistic aesthetic akin to Phantasmagoria. While impressive for 1993, the compression artifacts, stilted acting, and inconsistent green-screen integration often veer into unintentional comedy, undermining its serious themes. The jump from the abstract charm of pixel art to the uncanny valley of digitization is jarring.

Sound design is sparse but effective. The early games feature tense, moody synth tracks typical of late-’80s PC adventures, with memorable, driving themes for chase sequences. PQ3‘s soundtrack is more atmospheric. Open Season uses a dark, ambient score and sparse, impactful sound effects for its crime scenes. The iconic “Game-Over Man” narration, provided by Jim Walls himself in PQII and III, is a brilliant piece of audio design—a weary, disappointed mentor telling you exactly how and why you failed, adding immense personality and consequence to death.

Reception & Legacy: Cult Classic with a Cracked Foundation

Upon release, the first three games were critically praised for their unprecedented realism and “Shown Their Work” ethos. Computer Gaming World highlighted the authentic procedures. Their use as a training simulator for officers, as suggested by some sources, speaks to their perceived accuracy. However, their difficulty was legendary, often criticized as “Guide Dang It!” and requiring a meticulous, manual-dependent playstyle that alienated many adventure gamers.

Open Season received a more mixed, often negative, reception from series fans. Its shift to graphic violence and FMV-driven storytelling was seen as a betrayal of the series’ core identity. While technically impressive, its procedural depth was shallower, and its tonal inconsistency (oscillating between gritty crime drama and B-movie schlock) left it feeling unfocused. Commercially, the series was always a solid, if niche, performer for Sierra.

The legacy of the Police Quest series is profound but bifurcated. The first three games are foundational texts for the police procedural game genre, directly influencing later titles like L.A. Noire and the more serious entries in the SWAT series. Their emphasis on evidence, procedure, and consequence can be felt in modern detective and investigation games. The series’ pivot with SWAT (PQ5) and SWAT 2 (PQ6) birthed the entire tactical shooter subgenre. However, the Police Quest name itself faded, a victim of its own identity crisis post-Gates.

The collection itself has a fascinating release history, as documented in the Fandom Omnipedia. From the 1995 Four Most Wanted (which included a Daryl Gates interview and LAPD manual extras) to the 2006 Step Behind the Badge (with DOSBox), the compilation has been a vehicles for preservation. The GOG.com releases (2011/2014) and the Steam release (2016) are the most accessible and functional modern iterations, though they remain largely barebones, missing many of the physical extras ( manuals, posters) of the original 1995 box. User scores on Metacritic and Steam are “Generally Favorable” (8.1/10, “Very Positive”), with a clear consensus: the first three games are essential historical artifacts, while Open Season is a fascinating but flawed footnote. The failed 2013 Precinct Kickstarter, led by Jim Walls, is a poignant capstone, demonstrating the enduring passion for this style of game but also the commercial challenges of reviving such a niche, demanding format.

Conclusion: An Imperfect Badge, An Undeniable Legacy

The Police Quest Collection is not a perfectly curated anthology. It includes the peak of the series’ innovative, punishing design (PQ1-3) alongside its most divisive and tonally confused entry (Open Season). It is a document of a specific moment in gaming where a major studio, armed with real-world expertise, attempted to create a game that was more simulator than fantasy, where the hero’s greatest weapon was not a gun but his knowledge of penal code and procedure. Its gameplay can be archaic, its interface clunky, and its FMV sequences embarrassingly dated. Yet, its commitment to a singular, difficult vision—making you feel the weight of the badge and the crushing boredom and sudden terror of patrol work—remains unmatched.

For the historian, this collection is invaluable. It charts the evolution of Sierra’s engine technology, the move from parser to point-and-click, and the experimentation with full-motion video. It captures the creative rupture between Jim Walls’ procedural realism and Daryl Gates’ cinematic sensationalism. For the player, it offers four distinct, deeply atmospheric stories. The first three are challenging, rewarding, and narratively cohesive adventures that earn their “Earn Your Happy Ending” moments. The fourth is a gritty, violent, and stylistically bold detour that, while flawed, showcases Sierra’s technical ambition.

Ultimately, the Police Quest Collection earns its place in the pantheon not as a flawless masterpiece, but as a crucial, preserved artifact. It reminds us that adventure games could be about more than puzzles and jokes; they could be about duty, ethics, and the messy reality of systems. It stands as a testament to an era of bold, idiosyncratic design, where a game could—and would—kill you for forgetting to look both ways before crossing the street. That is a legacy worth preserving, flaws and all.

Final Verdict: 8/10 – A historic compilation with uneven quality, but its first three entries are essential, demanding, and brilliant examples of narrative design and genre-defining simulation.