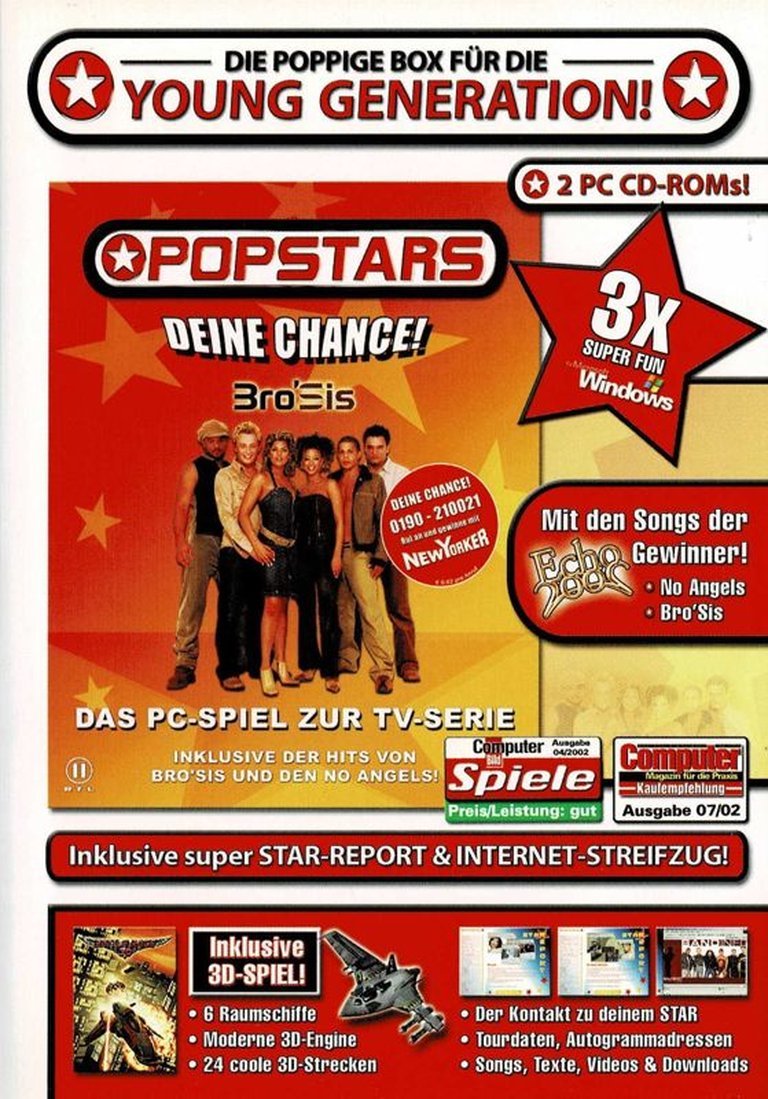

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Blackstar Interactive GmbH

- Developer: Ixyom Digital Studios

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Music, rhythm

- Setting: Casting show, Television

Description

Popstars: Deine Chance is a licensed music rhythm game based on the German television casting show Popstars. Players assume the role of a contestant and must prove their talent through four minigames: singing by pressing buttons in sync with lyrics, sorting text blocks for lyrics, dancing with 18 move combinations, and coordinating group dances, all set to songs from bands like No Angels and Bro’Sis, with jury judgments and eliminations across different locations culminating in a winner.

Popstars: Deine Chance Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : Popstars: Deine Chance brings backstage drama and chart-topping excitement straight to your living room.

Popstars: Deine Chance: A Critical Autopsy of a Licensed Rhythm Game Artifact

Introduction: The Unlikely Star of a German Evening

In the vast,老鼠-infested archives of early-2000s European game development, few titles encapsulate the volatile marriage of fleeting pop-culture mania and throwaway software quite like Popstars: Deine Chance. Released in January 2002 for Windows, this officially licensed game adaptation of the German reality TV phenomenon Popstars is not a monument to great game design. It is, instead, a meticulously preserved specimen of a specific moment: the peak of the show’s cultural dominance, the nascent and often clumsy era of rhythm game experimentation, and the Western world’s often-exploitative approach to television tie-in games. This review argues that while Popstars: Deine Chance fails utterly as a compelling interactive experience, its value lies in its brutal honesty. It is a transparent, unvarnished simulation of the Popstars competition’s core mechanics—audition, perform, be judged, survive—rendered with a technical austerity that inadvertently critiques the very spectacle it tries to emulate. To understand its place in history is to understand the economics and aesthetics of licensed schlock at the turn of the millennium.

Development History & Context: The Ixyom Assembly Line

The game was developed by Ixyom Digital Studios GmbH, a German studio whose portfolio, as chronicled in MobyGames credits, reveals a pattern of licensed and budget-conscious titles (Fast Food Tycoon, Marble Master, Bundesliga Manager 98). This was not a boutique developer chasing artistic vision; this was a production house operating within a proven, if low-ceiling, business model. The project was published by Blackstar Interactive GmbH, a label specializing in accessible, often licensed, titles for the German-speaking market.

The studio’s vision, as dictated by the license, was purely functional: replicate the Popstars format. There was no aspiration to innovate beyond the show’s structure. Led by General Manager Christopher Schmitz and Game Designer Paul Guillaumon (who also handled texts and quality assurance), the team approached the task as a series of discrete minigame modules. The technological constraints of 2001/2002 for a small PC-focused studio were significant. The game runs on Windows, supports only keyboard input, and utilizes simple 3D models with low polygon counts and famously wooden animations—a fact repeatedly noted by critics. The 3D graphics were handled by Jörg Tobergte and Andre Schneider, while Kay Poprawe and Oliver Papoulias managed 2D elements. Sound, by Alexander Knorr, was a straightforward matter of licensing nine tracks and implementing basic triggered audio for the minigames.

The gaming landscape at the time was seeing the rise of dedicated rhythm franchises like Dance Dance Revolution (Arcade, 1998; PS1, 1999) and Parappa the Rapper (PS1, 1996/1997 in the West), which emphasized pattern memorization and physical feedback. Popstars: Deine Chance is fundamentally incompatible with this paradigm. It strips away physical peripherals (the “dance pad”) and even the fundamental “music” aspect, reducing singing to a single-button press and dancing to a sequence of numpad inputs. It represents a “budget rhythm game” concept, where the perceived barrier to entry is merely a keyboard, but this abstraction fatally wounds the intended fantasy of performance.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Spectacle of Elimination

The game’s narrative is not a story but a procedural framework directly lifted from the TV show. The player assumes the role of an anonymous, wooden avatar contestant. There is no character creation, no backstory, no dialogue choices. You are a placeholder body in a simulation of the Popstars machine. The plot is the format itself: a competition whittling down a group of hopefuls through weekly “shows” in different “locations” (stages with minimal visual differentiation).

The themes present are those of the reality TV genre, albeit rendered in a stark, algorithmic manner:

1. Meritocratic Performance Anxiety: Success is measured in numeric points from a faceless jury after each discrete skill test. There is no room for “personality” or “story,” only quantifiable output.

2. The Tyranny of Comparison (Elimination): The core loop is an elimination tournament. After the combined scores of the four minigames, the lowest performer is shown the door. This creates a relentless, tensionless pressure because the player has no control over others’ scores. The “narrative” climax is simply a text or brief clip announcing an elimination, often your own.

3. Performative Labor: The minigames are not artistic expression but repetitive, tactile tasks. “Singing” is a reaction test. “Lyrics” is a block-sorting puzzle. “Dancing” is a sequence of button presses. The fantasy of becoming a pop star is replaced by the reality of performing digitized, menial labor for a jury’s approval.

4. Licensed Authenticity as Battering Ram: The game’s only narrative “weight” comes from its licensed assets: nine songs from the Popstars-produced bands No Angels and Bro’Sis, and穿插 (intercut) 15 video snippets from the actual television broadcasts. These clips are not integrated into a story; they are rewards or brief respites that constantly remind the player they are playing a secondary, inferior product. They underscore the theme that the real spectacle is on TV, and this game is a pale, interactive footnote.

The dialogue and characters are nonexistent beyond the jury’s score tallies and the occasional canned elimination phrase. The “contestants” are indistinguishable 3D models with “frozen faces” and “miserable grimaces,” as PC Games (Germany) seethed, suffering from “apparent facial paralysis.” This is a profound thematic irony: a game about pop stardom presents its stars as hideous, expressionless puppets, perhaps the most honest visual representation of the “manufactured band” critique ever inadvertently created.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Four-Part Grind

The entire gameplay experience is a cycle of four minigames, repeated until elimination or victory:

1. Singing: A song plays. A line of lyrics scrolls. When the first word of the next line is due, a specific key (or set of keys) must be pressed. Analysis: This is a pure rhythm/reaction minigame with zero connection to actual singing. The “optical clues” on lower difficulties are essential, as the audio cue alone is often unclear. It’s repetitive, playing the same 9 songs repeatedly.

2. Lyrics: Text blocks of a song’s lyrics are scrambled. The player must arrange them into the correct order. Analysis: This is a simple puzzle minigame that breaks the rhythm flow. Its inclusion feels like a mandated “variety” checkbox rather than a meaningful test of popstar aptitude. It tests memory or rapid reading, not performance.

3. Dancing: The player controls a 3D model on a stage. 18 different “dance moves” are each assigned to a number key (likely on the numpad). A sequence of numbers appears on screen, and the player must press them in order with precise timing. Analysis: The core of the game’s “rhythm” claim, but it is wholly abstract. There is no sense of movement, only inputting a code. The “18 moves” are cosmetic animations triggered correctly or incorrectly. Critics noted the lack of grace: the models move with “the elegance of a wrestler” (PC Games) or simply “wobble and jiggle” (Computer Bild Spiele). The sequences grow longer, but the challenge is purely mnemonic and tactile.

4. Group Dancing: Identical to the solo dancing minigame, but the player’s timing must align with AI-controlled “fellow dancers.” The prompt shows multiple sets of inputs for the group, and the player must hit their part in sync with the AI’s visual cue. Analysis: The most conceptually interesting but technically bare mode. It simulates “synchronization” but without any real consequence for the AI partners. If you fail, your character stumbles; the group performance degrades visually. It adds a layer of pressure but exposes the hollowness of the system—there is no “choreography” being created, just simultaneous button presses.

Core Loop & Progression: After each “show” (a set of these four minigames), scores are totaled. The lowest contestant is eliminated. The game progresses through a series of static stage locations (rehearsal room, small club, big arena, etc.). There is no character progression. You do not unlock new moves, songs, or outfits. Your only “skill” comes from internalizing the 18 dance move codes and the lyrics patterns for the nine songs. The UI is functional but sparse: a score counter, the minigame prompt, and the 3D performance view.

Innovative or Flawed Systems: The “Group Dancing” concept of simulated synchronization is the only glimmer of a systemic idea that could have been expanded. Conversely, the entire difficulty system is inverted. Lower difficulties provide “optical clues” (likely highlighted keys or slower prompts), making the game slightly more accessible but also more patronizing. The highest difficulty strips these away, but the underlying task remains simple pattern recognition, not true rhythm mastery. The multiplayer modes (Hot Seat, Internet) are listed in specs but are functionally just taking turns on the same solo elimination loop, with no direct competition between players.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Glossy Void

The game attempts to simulate the atmosphere of a televised talent show. Stages feature spotlights, camera flashes (simulated by on-screen effects), and cheering crowd sounds. The visual direction aims for a “glossy TV sheen” (Retro Replay) but lands in the “uncanny valley of pop.” The 3D character models are low-poly, with stiff animations and, as universally panned by critics, “missratene Fratzen” (miserable, botched faces) with no expressive capability (Computer Bild Spiele). They lack the sparkle of pop stardom, looking more like department store mannequins fitted with cheap wigs. The venues, while distinct in backdrop, are empty and static. The art does not build a world; it builds a soundstage, and a poorly decorated one at that.

The sound design is a study in repetition. The nine tracks from No Angels and Bro’Sis are the game’s sole audio landscape (aside from UI clicks). They play in full during minigames, meaning you will hear “I Believe” by Bro’Sis upwards of 15 times in a single playthrough, as Computer Bild Spiele noted with despair: “spätestens, wenn zum siebten Mal in Folge ‘I Believe’ von Bro’Sis ‘rauf- und ‘runtergenudelt wird, verginge auch Ihnen das Lachen.” (By the seventh time in a row ‘I Believe’ by Bro’Sis is played over and over, you’d stop laughing too). The game weaponizes its own licensed music against player enjoyment. The inclusion of actual TV show clips is the only element that breaks the monotony, but they serve as a constant, taunting reminder of the superior, un-interactive product.

These elements combine to create an experience that feels not like a pop star’s dream, but like a corporate training simulator for repetitive stress injury. The world is a sterile, joyless stage, and the soundtrack is a weaponized loop of contractual obligations.

Reception & Legacy: A Symphony of Contempt

The critical reception at launch was a masterclass in unified disdain. The aggregated MobyGames critic score of 35% is almost charitable.

* GameStar (Germany) delivered the most scathing verdict (15%), calling it a “kruder Mix aus Pseudo-Tanzspielchen” (crazy mix of pseudo-dance games) and a product where “even hardened fans would feel cheated.”

* PC Games (30%) highlighted the soul-crushing repetition and the “Nervenkitzel!” (thrill!) of such mundane tasks.

* Game Captain (29%) lamented the wasted potential of an “überaus spannendes Thema” (very exciting topic) executed with “unsäglich stumpfen Aufgaben” (unspeakably dull tasks), “miese Grafik” (lousy graphics), and no voice acting.

* Only Computer Bild Spiele (65%) offered faint praise, acknowledging the character animations are “ganz nett” (quite nice) before launching into the same criticism about repetitive songs and ugly faces. Their final grade was “befriedigend” (satisfactory)—a German school-grade meaning mediocre—a verdict the review itself thoroughly undermines.

Commercially, its existence in bundles like Extreme Value Pack 2 and Totally TV suggests it was treated as pure inventory—a cheap box-checker for retailers. The MobyGames player data shows a single rating (1.4/5), implying near-zero engagement or cultural memory.

Its legacy is one of cautionary footnote. It is not cited as an influence on any major genre. Instead, it stands as:

1. A peak example of the “TV Show Cash-Grab” subgenre of licensed games, where minimal effort meets maximum brand recognition in a specific regional market.

2. An early, UI-focused iteration of the reality TV simulation game, predating more narrative-driven attempts. Its purely systemic, mechanical translation of the format is its most academically interesting feature, albeit a failed one.

3. A stark contrast to the success of Popstars as a music franchise, highlighting the vast gulf between creating pop stars and simulating the process in a way that feels meaningful.

4. A preserved artifact in archives like My Abandonware and MobyGames, where its “above-average licensed title” description (My Abandonware) is likely a statistical artifact of its sheer existence and rarity, not quality.

Conclusion: The Verdict on a Calculated Risk

Popstars: Deine Chance is not a game that fails because it is ambitious. It fails because its ambition was purely contractual. It sought to translate a televised circus of personality, drama, and singing into four disconnected, repetitive keyboard exercises, draped in the legally-mandated silks of No Angels and Bro’Sis. The development team at Ixyom Digital Studios executed this narrow brief with a competence that only highlights the创意 bankruptcy of the concept itself. The graphics are functional but lifeless, the sound is a prison of repetition, and the gameplay is a hollowed-out shell of the very competition it depicts.

Its place in video game history is secure, not as a masterpiece, but as a perfect cultural artifact. It is the gaming equivalent of a Popstars-branded bubble gum card or cheap poster—forgettable, disposable, yet perfectly capturing the cheap, mass-produced feel of its source material at a specific time. It proves that a license can provide authentic music and branding, but cannot manufacture engagement, artistry, or fun. For the historian, it is invaluable evidence. For the player, it is a five-minute curiosity, after which the only lingering emotion is a profound appreciation for the developers who did try to make something meaningful from the pop-star dream, rather than just a product to be stocked alongside the show’sDVD box sets. The final, definitive verdict: A 2/10 experience that earns a 6/10 for historical documentation, a testament to the era when TV networks and game publishers looked at each other and saw dollar signs, not design documents.