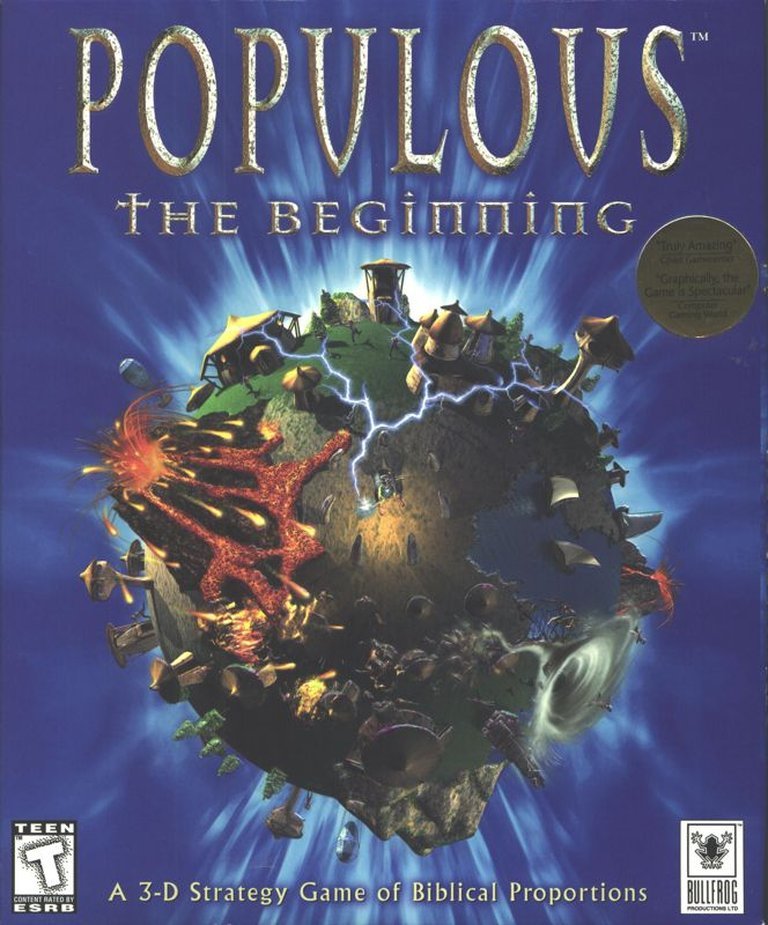

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: PlayStation 3, PlayStation, PS Vita, PSP, Windows

- Publisher: Dice Multi Media Europe B.V., Electronic Arts, Inc., Sold Out Sales & Marketing Ltd.

- Developer: Bullfrog Productions, Ltd.

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Base building, Natural disasters, Real-time strategy, Spell casting, Unit training

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 79/100

Description

Populous: The Beginning is a fantasy real-time strategy god game and the third entry in the Populous series, featuring 3D graphics. Players take on the role of a shaman leading a tribe on tiny planets, where they must chop trees to build huts, manage population growth based on housing, train units like fighters and priests, and acquire spells through prayer at shrines—many of which invoke natural disasters such as tornadoes and volcanic eruptions. The game includes a single-player campaign across multiple worlds and supports online multiplayer for competitive play.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Populous: The Beginning

Populous: The Beginning Free Download

Populous: The Beginning Patches & Updates

Populous: The Beginning Mods

Populous: The Beginning Guides & Walkthroughs

Populous: The Beginning Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (88/100): This isn’t a Populous for the 3D-accelerator age; it’s a game that takes inspiration from the original, but little else.

imdb.com (80/100): Never mind the ethical implications, playing God is *fun*

ign.com (70/100): Populous: The Beginning takes a slightly different approach to strategy

Populous: The Beginning Cheats & Codes

PlayStation

Enter the following codes using a Gameshark device on PlayStation.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| D00D851C ???? | Joker Command |

| 801E5F70 0384 | Infinite Time |

| 80165058 0004 | Game Always Thinks You Have Followers |

| 801650F8 0004 | Game Always Thinks You Have Followers |

| 801CD282 3900 | Game Always Thinks You Have Followers |

| 801DC2AC 0000 | Max Spell Charge Rate |

| 801DC2B0 FFFF | Have All Build Options |

| 301DC2C6 0004 | Have Invincibility Spell |

| 301DC2CC 0004 | Have Land Bridge Spell |

| 301DC2FD0 0004 | Have Volcano Spell |

| 301DC2C3 0004 | Have Lightning Spell |

| 301DC2C7 0004 | Have Hypnotize Spell |

| 301DC2C9 0004 | Have Firestorm Spell |

| 301DC2D1 0004 | Have Convert Spell |

| 301DC2D2 0004 | Have Armageddon Spell |

| 301DC2C5 0004 | Have Swarm Spell |

| 301DC2D3 0004 | Have Magical Shield Spell |

| 301DC2C4 0004 | Have Tornado Spell |

| 301DC2CE 0004 | Have Earthquake Spell |

| 301DC2CD 0004 | Have Angel of Death Spell |

| 301DC2CA 0004 | Have Erode Spell |

| 301DC2CB 0004 | Have Swamp Spell |

| 301DC2CF 0004 | Have Flatten Spell |

| 801DC2C2 FFFF | Have All Shamen Spells |

| 801DC2C4 FFFF | Have All Shamen Spells |

| 801DC2C6 FFFF | Have All Shamen Spells |

| 801DC2C8 FFFF | Have All Shamen Spells |

| 801DC2CA FFFF | Have All Shamen Spells |

| 801DC2CC FFFF | Have All Shamen Spells |

| 801DC2CE FFFF | Have All Shamen Spells |

| 801DC2D0 FFFF | Have All Shamen Spells |

| 801DC2D2 FFFF | Have All Shamen Spells |

| 80164684 0001 | Unlock Night Falls Level |

| 80164688 0001 | Unlock Crisis of Faith Level |

| 8016468C 0001 | Unlock Combined Forces Level |

| 80164690 0001 | Unlock Death from Above Levels |

| 80164694 0001 | Unlock Building Bridges Levels |

| 80164698 0001 | Unlock Unseen Enemy Levels |

| 8016469C 0001 | Unlock Continental Divide Levels |

| 801646A0 0001 | Unlock Fire in the Mists Level |

| 801646A4 0001 | Unlock From the Depth’s Level |

| 801646A8 0001 | Unlock Treacherous Souls Level |

| 801646AC 0001 | Unlock An Easy Target Level |

| 801646B0 0001 | Unlock Aerial Bombardment Level |

| 801646B4 0001 | Unlock Attacked On All Sides Level |

| 801646B8 0001 | Unlock Incarcerated Level |

| 801646BC 0001 | Unlock Middle Ground Level |

| 801646C0 0001 | Unlock Head Hunter Level |

| 801646C4 0001 | Unlock Unlikely Allies Level |

| 801646C8 0001 | Unlock Archipelago Level |

| 801646CC 0001 | Unlock Fractured Earth Level |

| 801646D4 0001 | Unlock Solo Levels |

| 801646D8 0001 | Unlock Inferno Level |

| 801646DC 0001 | Unlock Journey’s Level |

| 801646E0 0001 | Unlock Journey’s End 2 Level |

| 800D8BA4 00?? | Level Modifier – use with quantity digits from 00 to 18 to select level |

PC

Press [Tab] + [F11], type ‘byrne’ to enable cheat mode, then use the following key combinations:

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| TAB + F1 | Faster mana regen |

| TAB + F2 | Free spells |

| TAB + F3 | All spells |

| TAB + F4 | All buildings |

| TAB + F5 | Max mana |

Populous: The Beginning – A Divine Gamble Between Genres

Introduction: The God Who Became Human

In the pantheon of video game history, few series have birthed an entire genre as definitively as Populous. Peter Molyneux and Bullfrog Productions’ 1989 landmark didn’t just invent the “god game”; it established a template of divine omnipotence and indirect influence that echoed for decades. Yet by 1998, the landscape had shifted. Real-time strategy (RTS) titans like Command & Conquer and StarCraft dominated the strategy conversation, and the serene, awe-inspiring god’s-eye view of Populous felt increasingly anachronistic. Populous: The Beginning was Bullfrog’s audacious, flawed, and fascinating answer: a deliberate, almost defiant reinvention that traded omniscient detachment for the intimate, chaotic burden of a mortal shaman’s quest for apotheosis. It is a game caught between two worlds—the contemplative, terraforming legacy of its lineage and the frenetic, micro-management demands of the modern RTS. This tension defines its genius and its frustration. Populous: The Beginning is not the Populous fans expected, nor is it a pure RTS. It is something stranger, more personal, and ultimately more divisive: a game about the loss of divine privilege, wrestling with the very mechanics it helped inspire, and a cultural artifact whose thematic ambitions are as questionable as its gameplay is innovative.

Development History & Context: The Post-Molyneux Crucible

To understand The Beginning, one must first understand the vacuum it was born into. Bullfrog Productions, after the landmark successes of Populous (1989) and Populous II (1991), had become a studio synonymous with genre-bending creativity under the visionary, mercurial leadership of Peter Molyneux. However, the development of Dungeon Keeper (1997) strained Molyneux’s relationship with publisher Electronic Arts (EA), culminating in his unceremonious departure shortly after its release. He left to form Lionhead Studios, taking with him the charismatic, philosophical mantle of Bullfrog’s “big picture” designer.

The Beginning was thus the first Populous game developed without its creator. The studio, now firmly under EA’s corporate umbrella, faced immense pressure. Populous II had been a critical but commercial successor, but the four-year gap to The Beginning was unprecedented. As noted in development previews and retrospective analysis, Bullfrog was waiting for hardware to catch up. The original Populous’s charm lay in its elegant isometric abstraction; The Beginning’s ambition demanded true 3D graphics and real-time terrain deformation. The team repurposed and heavily upgraded the engine from Magic Carpet, creating a curved-perspective globe where players could freely rotate and zoom—a technical showcase for the 3D accelerator era.

This technological leap forced a philosophical reckoning. The original power fantasy of reshaping land with a click felt incongruous with a tangible, rotatable 3D world where the player’s avatar—a shaman—was a physically present, vulnerable unit. The design pivot was radical: the god was gone, replaced by a leader. The “smart villagers” who automatically built and worshipped, a feature lauded in previews, was both a blessing and a curse, streamlining base-building but creating control issues in combat. The original working title, Populous: The Third Coming, hints at an intent to directly continue the saga, but it was quietly changed to The Beginning before beta, signaling a reboot and a thematic reset—a story set before the original games, explaining why the player was “only” a shaman.

The development team, led by producer Stuart Whyte and project leader Alan Wright, was large (263 credited on MobyGames) and marked by the usual Bullfrog collaboration. Composer Mark Knight crafted a moody, atmospheric score encoded in MP3—a notable technical detail for the time—relying on New Age instrumentation and tribal motifs to sell the setting. Yet, as Hardcore Gaming 101’s critique underscores, this aesthetic choice would become a central point of contention, layering a veneer of “primitive” mysticism over mechanics that玩家 had to often manage with frustrating imprecision. The game was ready for its late-1998 launch, a flagship EA title arriving in a crowded season that included Half-Life, a game whose narrative and technological leaps would make The Beginning’s own innovations feel somewhat niche.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Controversial Prehistory

Populous: The Beginning presents itself as a prequel, set in a primordial solar system inhabited by four tribes: the player’s unnamed Blue tribe, and the hostile Matak (Green), Chumara (Yellow), and Dakini (Red). The narrative premise is stark and mythic: the player’s female shaman must conquer all other tribes and their shamans to achieve ultimate godhood. The campaign spans 25 levels, each a planet, with a simple win condition—usually annihilation—and a clear progression of power.

On the surface, it’s a classic “conquer the world” RTS story. The depth, however, is almost entirely environmental and mechanical, not literary. There are no meaningful cutscenes (a point of criticism in PC Gamer and GameStar reviews), no character development, and the “story” is a skeletal justification for the gameplay loop. The tribes are defined solely by color and a vague, homogenized “tribal” aesthetic. The game’s world-building relies on a problematic and culturally reductive visual shorthand: totem poles, Moai statues, Mayan-inspired “Vaults of Knowledge,” and nonsensical grunting dialogue. Followers speak in a fabricated, pseudo-tribal language, and the architecture synthesizes Polynesian, Native American, and Mesoamerican symbols into an ahistorical “primitive” mishmash.

This is where The Beginning’s thematic aspirations collide with modern sensibilities. As the Hardcore Gaming 101 analysis incisively argues, the game embodies a “magical Native American” trope, presenting a fictional, de-indigenized “savage” past as a playground for Western fantasy. It’s a narrative of colonial conquest disguised as mythic ascent—the shaman’s journey to godhood is literally the subjugation and eradication of rival “primitive” cultures. The game offers no commentary on this; it presents the genocide as a natural, even noble, part of a power fantasy. The irony is profound: a series about godly creation devolves into a story of tribal supremacy, wrapped in a aesthetic of “nostalgia for the colonized culture as it was ‘traditionally’” (Renato Rosaldo’s “Imperialist Nostalgia” as cited). The shaman, a female protagonist, is a notable detail (credited on MobyGames as “Protagonist: Female”), but her role is not one of cultural preservation or complex leadership—it is of violent expansion. The narrative is not a story; it is a skin for the gameplay, and a deeply problematic one at that. Its “mythos” is a colonial fantasy, a layer of thematic grime that stains an otherwise mechanically interesting game.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The RTS God Game That Forgot Its Gods

The Beginning’s core revolution is its shift from indirect godhood to direct, vulnerable leadership. The player is embodied by the Shaman, a weak but pivotal unit who casts spells and must be protected. This single change cascades through every system.

Core Loop & Progression: Each level is a contained spherical map (projected as a torus). The goal is typically to eradicate all enemy tribes. The player starts with a handful of Braves (basic builders/fighters) and a Reincarnation Site (a stone circle). Progression is twofold: population growth and spell acquisition. Braves automatically build huts when given wood (chopped from trees). Larger huts house more Braves, who in turn generate Mana (spell resource) faster and can be trained into specialized units: Warriors (melee), Fire Warriors (ranged), Preachers (convert enemy units), and Spies (sabotage). New spells and buildings are learned by “worshipping” at artifacts: Stone Heads (one-off spells), Obelisks (replenishable spells), Totem Poles (cataclysmic effects), and Vaults of Knowledge (permanent unlocks). This creates a compelling “loot” system; each level promises a new tool, driving the player forward.

The Spellbook: Divine Wrath Made Manual: The spells are the star. They range from tactical (Blast—the Shaman’s basic push/knockback, vital for defense and positioning), Lightning (sets fires), Convert (on Wildmen and sometimes troops), and Invisibility, to strategic Landbridge (connects landmasses), Erode (sinks terrain), and Flatten (levels ground). The cataclysmic tier—Tornado, Earthquake, Swamp, Firestorm, Angel of Death, and the spectacular Volcano—are game-warping events. The physics-based interactions are brilliant: a Volcano on an ocean creates an island; a Tornado demolishes structures but leaves salvageable wood; an Earthquake can drop enemy buildings into the sea. Spells have limited charges or require time to recharge based on follower count, forcing careful curation. The Shaman’s vulnerability means spellcasting is a risk/reward exercise—get too close, and an enemy Warrior can end the game.

The AI & Unit Control Quagmire: This is the game’s most infamous flaw. Braves automatically perform tasks (build, chop wood, worship), which is efficient but leads to a critical lack of precision. In the heat of battle, selecting a specific group of units is a chore; they often ignore orders or pathfind erratically. As GameSpot noted, units “often act with a mind of their own,” sometimes charging to their deaths while the player formulates a plan. The AI for enemy tribes is described as “pretty awesome” (CVG) in its challenge on higher difficulties, but also “a bit dense” (CGW) in its tactical decision-making, often allowing the player to exploit repetitive patterns. The tension between automated villagers and required micromanagement creates a clunky, frustrating interface that never feels as slick as contemporary RTS peers.

Puzzle-Platformer in an RTS Skin: Level design is not just about army size; it’s about puzzle-solving. Many missions have unique win conditions or environmental constraints (rising lava, limited spells, starting with no buildings). PC Action praised the “enormous impact of the 3D terrain and the sphere aspect” on strategy. The spherical maps mean navigation is non-linear; you can be ambushed from any direction. This, combined with the need to use specific spells or units to overcome obstacles (e.g., using boats or balloons to reach islands, using Spies to infiltrate), turns each level into a tactical vignette. However, Strategy Gaming Online and PC Gamer criticized a creeping repetitiveness—after dozens of hours, “watching hordes of little subjects bashing down buildings amidst tornadoes… becomes redundant.” The core mechanic is deep, but the campaign’s 25 levels, while well-crafted, can feel like a high-variance puzzle box rather than a dynamic war.

Multiplayer: The True Endgame: Where the single-player AI falters, human opponents shine. The multiplayer community, famously kept alive by fan projects like Populous: Reincarnated, discovered a brutal, deep competitive scene. The limited unit types (five total) and spells force extreme specialization and mastery of physics (Blast-knocks, tornado-riding, land-bridge snipes). The “Guest Spells” like Bloodlust and Ghost Army added further layers. As Hardcore Gaming 101 describes, high-level play involves constant building, rebuilding, and spell trickery the single-player campaign only hints at. This enduring legacy—with active matchmaking and ranked play nearly three decades later—is the ultimate testament to the gameplay’s latent depth, despite its rough edges.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A 3D Revolution with a Primitive Skin

Technically, The Beginning was a marvel. It was the first Populous in full 3D, with a smoothly rotating, zoomable globe. The landscape is vibrant and textured with altitude-based blending, creating distinct biomes from lush jungles to volcanic hellscapes. The character models, however, are 2D sprites on 3D terrain—a practical compromise that gave them a charming, cartoonish quality (the little “runs” your followers do are noted in MobyGames trivia). The art direction is bombastic: obelisks glow, volcanoes erupt with fiery polygons, and tornadoes tear throughDetailed structures. The cutscenes, particularly the final ascension sequence, were breathtaking for 1998 and hold a nostalgic weight for many fans.

The sound design complements this perfectly. Mark Knight’s score is an ambient, New Age soundtrack with tribal percussion and ethereal vocals, perfectly capturing the game’s faux-spiritual tone. The sound of a crowd of Braves chanting, the roar of a Volcano, the crack of Lightning—all are iconic and punchy. The “celebration” mechanic, where followers form conga lines and Firewarriors shoot fireworks, adds a delightful layer of emergent, whimsical personality.

Yet, this aesthetic polish is the very vehicle for the game’s problematic themes. The visual language is a pastiche of indigenous symbols, flattened into generic “tribal” savagery. The “wildmen” are bearded, loin-clothed grunters. The architecture is a blend of Easter Island, generic “Indian” teepee-like huts, and Mesoamerican pyramids. It’s a world built not on cultural specificity but on Western archaeological fantasy—a “pre-history” imagined as a globally uniform state of magical primitive innocence. The beauty of the 3D engine makes this fantasy uncomfortably immersive, selling a colonialist vision of a world ready for conquest.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic Caught in the Crossfire

The Beginning launched to generally favorable reviews (82% on MobyGames, 80% on GameRankings), but the response was notably mixed compared to the near-universal acclaim of the original Populous.

Critical Praise: Critics widely lauded the stunning 3D graphics, the innovative spell system, and the compelling upgrade loop. Computer and Video Games called it one of the year’s best, praising its accessibility and challenging AI. PC Games (Germany) noted its “motivating hunt for new spells” and “exciting missions.” IGN’s Ward Trent was smitten with the immersive graphics, and Jeuxvideo.com declared it an “incontournable” (essential) of RTS. Awards followed: Computer Gaming World’s Runner-up for Best Strategy Game, PC Player (Germany)’s Best Remake, and Power Play’s Best RTS of 1998.

Critical Critique: The fractures were immediate and persistent. The central criticism was the identity crisis. Edge magazine bluntly stated it was “caught between the god game and RTS genres, and did not excel at either.” PC Gamer felt it failed to live up to the legacy, with missions becoming “mind-numbingly repetitive.” The control issues were a constant note: GameSpot found unit control “clunky and frustrating,” and the PlayStation port—reviewed harshly with scores as low as 41%—was universally panned for its unworkable controller scheme, long load times, and dumbed-down difficulty. IGN’s PlayStation review conceded it was an “excellent port” but that the controlpad was a severe limitation after mouse play. GameSpot’s verdict was damning: “It’s just a bad PlayStation game.”

The thematic critique, while less prevalent in 1998 reviews, has become central to its modern reappraisal. The simplistic, culturally取样的narrative is now widely seen as a major weakness, a “narrative desert” as HG101 puts it, that stands in stark contrast to the sophisticated satire of Dungeon Keeper or the bureaucratic humor of Theme Hospital.

Commercial Performance & Longevity: It was a commercial success for EA, ranking among their best-selling PC games of Q3 1998. However, it was the last mainline Populous. Bullfrog was shuttered by EA in 2001. The official multiplayer servers died in 2004, but the community, epitomized by Populous: Reincarnated, refused to let it die. They created matchmakers, hosted tournaments, and kept the competitive scene alive. This fan dedication is a unique form of legacy, a testament to the game’s underlying mechanical excellence that transcends its flaws. The 1999 expansion, Undiscovered Worlds, added 12 challenging single-player and multiplayer maps, but is largely forgotten outside the hardcore community.

Its influence is subtle but present. The MOBA-like focus on a vulnerable, spell-casting hero with a team of semi-autonomous minions prefigures later genre hybrids. The emphasis on terrain as a dynamic, physics-driven weapon can be felt in games like From Dust (also by Éric Chahi) and even the environmental puzzles of Warcraft III. Yet, it never spawned a direct successor. The spirit of Populous lived on in Molyneux’s Black & White and later Godus, but the tight, puzzle-like, competitive RTS structure of The Beginning was uniquely its own, a dead-end branch on the god-game tree that some Cult of Coherence players still tend.

Conclusion: A Flawed Masterpiece of Its Moment

Populous: The Beginning is a profound contradiction. It is a game that abandoned the very essence of its name—the populous, the people, as an autonomous, emergent force—only to place the player in the messy, micro-managing role of a mortal leader. Its world is a beautiful, 3D playground built on a foundation of cultural insensitivity. Its mechanics are deep, physics-rich, and strategically varied, yet sullied by clunky pathfinding and control issues that frustrate as much as they delight.

Its place in history is not as the savior of the god-game genre, nor as a pure RTS classic. It is instead a fascinating what-if and a transitional artifact. It represents Bullfrog post-Molyneux: technically ambitious, mechanically inventive, but themally adrift. It attempted to bridge the contemplative past with the aggressive present of strategy gaming and succeeded only partially, creating a hybrid that satisfied neither purist completely. Yet, within that messy middle ground, it found a dedicated niche. The sheer joy of unleashing a Volcano to reshape an archipelago, the tension of protecting your Shaman while your Braves build, the puzzle-like satisfaction of solving a planet’s conquest—these moments are uniquely, brilliantly Populous.

For the historian, it is a crucial case study in studio evolution, genre hybridization, and the pitfalls of cultural shorthand in game design. For the player, it is a challenging, atmospheric, and deeply rewarding experience if one can overcome its interface hurdles and set aside its regressive narrative. Its legacy is twofold: a dormant franchise that ended a legendary series on a note of ambitious compromise, and a fiercely loyal community that kept its multiplayer heart beating for over 25 years. Populous: The Beginning is not the god game Populous was, nor the RTS StarCraft became. It is something else: a bold, beautiful, and broken testament to the idea that even the most revered formulas can—and perhaps must—be torn down to see what new, strange, and flawed things might be built in their place. It is a beginning that feels like an end, and an end that countless fans refused to accept.