- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Musicbank Ltd.

- Developer: Pantera Entertainment

- Genre: Skateboarding, Sports

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Racing, Skateboarding

Description

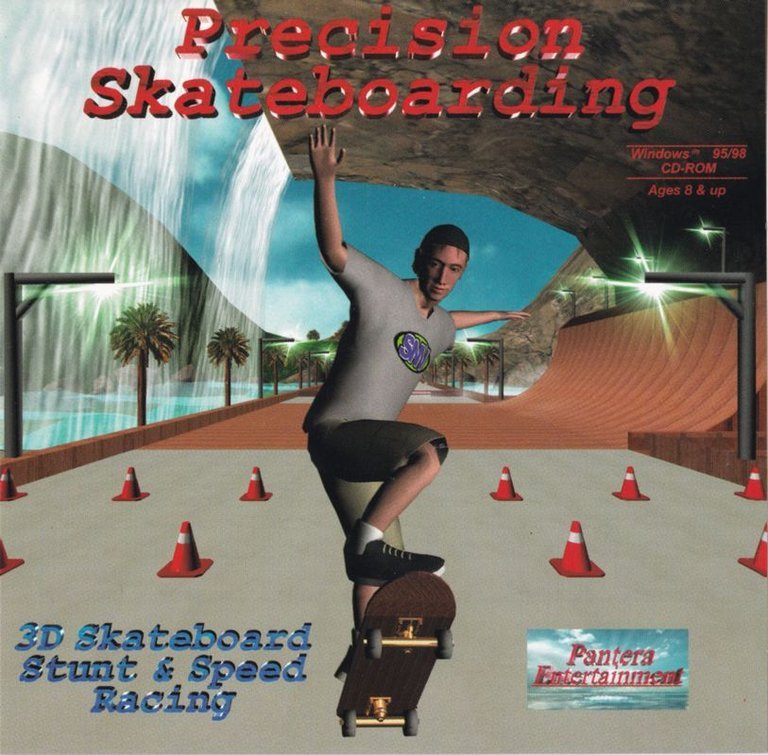

Precision Skateboarding is a 2003 Windows sports game where players compete in four skateboarding contests—Race Against The Clock, Half Pipe Race, Half Pipe Tournament, and Speed Track—using simple keyboard or joystick controls, but it lacks career progression, trick learning, or player choice, offering only alternate camera angles and sound effects.

Precision Skateboarding Free Download

Precision Skateboarding: Review

In the annals of skateboarding video games, few titles provoke as much bewildered curiosity as Precision Skateboarding. Released in the shadow of Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, this obscure Windows PC title attempted to carve out a niche with a minimalist, “precision” approach. Instead, it delivered a masterclass in missed opportunities—a game so clunky and underdeveloped that it became a punchline, yet one that retains a cult following among those who stumbled upon it during the early 2000s. As a professional game journalist and historian, I’ve dug through archives, player memories, and the scant surviving documentation to present an exhaustive review. Precision Skateboarding is more than just a bad game; it’s a time capsule of an era when the skateboarding genre was exploding, and not every contender could ride the wave.

Introduction: The Book Fair Phenomenon

Ask any millennial who bought games at Scholastic Book Fairs in the early 2000s, and you’ll likely hear tales of Harry Potter novels, Captain Underpants, and… skateboarding video games? That’s right. Amidst the educational fare, a handful of budget titles found their way onto those folding tables, peddled to kids with disposable allowance cash. Precision Skateboarding was one such title. For many, it was a first introduction to digital skateboarding—a rough, bewildering introduction that pale in comparison to the slick, licensed experiences dominating the shelves at Electronics Boutique or Toys “R” Us. Yet, for all its faults, it left an impression. This review sets out to dissect why Precision Skateboarding failed so spectacularly, how it fit into the broader evolution of skateboarding games, and why it still flickers in the collective memory of a small, nostalgia-tinged cohort.

My thesis: Precision Skateboarding stands as a fascinating case study in underfunded, low‑ambition sports game development. It exemplifies the perils of entering a rapidly innovating genre without a clear vision, technical competence, or understanding of what players truly wanted. Its extreme simplicity and broken controls encapsulate the worst excesses of early‑2000s budget gaming, while its very existence underscores the democratization of PC game distribution—for better or worse.

Development History & Context: The Obscure Studio and the Budget PC Era

The Developers: Pantera Entertainment (and Crystal Interactive?)

The credits for Precision Skateboarding are shrouded in ambiguity. MobyGames lists Pantera Entertainment as the developer, with Musicbank Ltd. as publisher. However, abandonware sites and retro gaming databases sometimes attribute development to Crystal Interactive Software, Inc., with publishers Megaware Multimedia B.V. alongside Musicbank. This suggests a tangled web of small, likely European or North American, entities operating under multiple names—a common practice among micro‑studios that churned out budget titles for the PC market. Pantera Entertainment left no other notable footprints in gaming history; a search yields no other commercial releases. Crystal Interactive Software, similarly obscure, is known for a handful of forgettable sports and casual games. The team behind Precision Skateboarding was almost certainly a tiny group, possibly even a single developer, working with limited resources and a tight deadline.

Intended Vision: “Precision” as a selling point?

The title itself—Precision Skateboarding—implies a focus on technical accuracy, perhaps a simulation‑style experience where the player must precisely time tricks and maneuvers. Early marketing (such as the brief descriptions on retail boxes and abandonware sites) promised “skill‑based gameplay” and “intricate tricks.” However, the final product reveals a profound disconnect between aspiration and execution. The game’s structure—four contest types with no progression—suggests the developers aimed for an arcade‑lite package but lacked the resources to flesh it out. It’s possible they envisioned a game that would run on even the most modest PCs, sacrificing graphical fidelity and content for accessibility. The result was a game that looked and felt dated even at the time of its release.

Technological Constraints: 640×480 and the Low‑Spec PC

The early 2000s were a transitional period for PC gaming. While 3D acceleration was becoming standard, many budget titles still targeted the vast install base of Windows 95/98/ME machines without dedicated 3D cards. Precision Skateboarding’s maximum resolution of 640×480 (as excoriated by PC Action magazine) is a dead giveaway: the game was built for software rendering or extremely basic DirectX support. Screenshots reveal blocky, pixelated environments and simple geometric shapes for skaters and obstacles. There is no evidence of texture mapping, lighting effects, or any of the visual polish that contemporaries like Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 (2000) showcased. This technical limitation was likely a cost‑saving measure—no need to license a robust 3D engine—but it made the game look immediately outdated and unappealing.

The Gaming Landscape: Tony Hawk’s Shadow

To understand Precision Skateboarding’s failure, one must remember the state of the skateboarding genre in the early 2000s. Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater (1999) had revolutionized the genre with its fluid controls, iconic punk soundtrack, real‑world professional skaters, and a compelling career mode. Its sequel, THPS 2 (2000), expanded the formula and received near‑perfect scores. Meanwhile, games like Thrasher: Skate and Destroy (1999) offered a more simulation‑oriented, brutally difficult alternative, and Grind Session (2000) attempted to compete with licensed pros and a “realistic” feel. By 2001, when Precision Skateboarding likely launched (some sources say 2003), the bar was high. Entering this arena required either a unique hook or a level of quality that could stand toe‑to‑toe with Activision’s powerhouse. Precision Skateboarding had neither. It lacked licensed skaters, a soundtrack, a career mode, and even basic graphical fidelity. Its sole distinction was its low price and availability in non‑traditional retail channels like Scholastic Book Fairs—a clear sign it was not meant to compete head‑to‑head with the big boys, but to capture an unsuspecting audience of kids who might not have known better.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Void of Story

No Plot, No Characters, No Dialogue

Unlike the narrative‑driven Tony Hawk’s Underground (2003) or even the context‑filled early THPS titles, Precision Skateboarding offers zero narrative. There is no story, no characters, no dialogue, and no setting beyond the abstract event names. The player is an invisible entity controlling a generic skater (if the sprite can even be called that) across a series of sterile courses. The game does not attempt to explain why you are skating, what the purpose of the events is, or who you are competing against. This absence is stark when compared to contemporaries: even ESPN X‑Games Skateboarding (2001) featured the X‑Games branding and a semblance of a competition framework.

Thematic Intent: “Precision” as a Misnomer

The title suggests a theme of technical mastery, but the gameplay betray this entirely. One could argue that the developers intended to create a game where success depended on exact timing—crouching to gain speed without sacrificing too much turning ability, or hitting jumps at the perfect moment. Yet the controls are so imprecise that achieving any level of consistency feels impossible. The theme of “precision” thus becomes ironic: the game itself is a lesson in imprecision. It’s possible the developers aspired to a minimalist, skill‑focused experience akin to early arcade titles like 720° (1986), but by 2001, players expected more depth and feedback. The theme falls flat, leaving only a hollow shell of events.

The Absence of Skate Culture

Skateboarding games thrive on their connection to skate culture—the music, the fashion, the attitude. Precision Skateboarding has none of these. There are no recognizable brands (Vans, DC, Element), no pro skaters, no punk rock tracks. The sound effects are presumably generic wheel noises and maybe a beep for jumps. This cultural vacuum makes the game feel sterile and disconnected from the very sport it attempts to simulate, further underscoring its failure to capture the spirit of skateboarding.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Framework of Frustration

The core of any game is its interactivity, and here Precision Skateboarding collapses under the weight of its own design.

Event Types and Core Loop

The game offers four contest types, described on MobyGames as:

1. Race Against The Clock – A timed run through a course, aiming for the best time.

2. Half Pipe Race – Score‑based halfpipe competition, likely rewarding spins and aerial maneuvers.

3. Half Pipe Tournament – Possibly a judged event or a head‑to‑head format, though details are scarce.

4. Speed Track – A straight‑line speed trial, perhaps on a downhill slope or a loop.

Reddit user bluespartans recalled an “underwater glass tube” level, suggesting at least one visually distinct environment within these types. However, the total number of events is “half a dozen” (six), so there are probably two variations per type or a couple of unique courses. The core loop is simple: pick an event, try to beat your high score/time, repeat. There is no career progression, no unlockable content, no difficulty scaling. Once you’ve mastered (or simply endured) an event, there is no incentive to return except sheer masochism or childhood stubbornness.

Controls: The Catastrophic Failure

The game’s control scheme is its most infamous aspect. According to the Moby description:

“The game is keyboard or joystick controlled, and the controls are straightforward, left/right to steer, jump, crouch – increases speed, and duck.”

Reddit users added crucial details: space bar to jump, duck (crouch) to increase speed at the expense of turning. This creates a rudimentary risk‑reward dynamic: you can go faster but become less maneuverable. On paper, this could have been an interesting mechanic—balancing speed against control is a staple of racing games. In practice, the steering is “catastrophically” unresponsive.

The German critic from PC Action delivered a scathing assessment:

“Die übelste Bruchlandung erleidet allerdings die katastrophale Steuerung: Weder mit Tastatur noch Gamepad ist es möglich, seinen Skater irgendwie auf Kurs zu halten.”

(“The worst crash landing is suffered by the catastrophic controls: Neither with keyboard nor gamepad is it possible to keep your skater on course.”)

This aligns with player memories. The Reddit user bluespartans noted: “the controls are so bad that it’s almost unplayable, but we still played it.” The steering feels loose and delayed; small inputs result in over‑ or under‑steering, making it nearly impossible to navigate narrow courses or maintain a line in the halfpipe. The crouch‑to‑accelerate mechanic is further undermined because the reduced turning radius combined with poor steering creates a vicious cycle: you go fast, can’t turn, crash, and repeat.

Lack of Progression and Customization

There is no career mode, no learning new tricks, and no choice of players. The player’s skill improvement is not reflected in-game; you simply get better at compensating for the bad controls. Unlike Tony Hawk games, where you could unlock new moves and skaters, Precision Skateboarding offers nothing to strive for. The absence of a progression system makes each session feel static and unrewarding. Even alternate camera angles (a lone feature mentioned in the Moby description) provide scant variety.

UI and Presentation

The user interface is presumably minimal: a timer or score counter, maybe a speedometer. There is no indication of trick names, combo meters, or anything that would give feedback on performance. This minimalist approach might have been intended to reduce clutter, but it also strips away any sense of accomplishment.

World‑Building, Art & Sound: A Skeleton of a World

Environments and Atmosphere

The four contest types take place in generic settings. The “underwater glass tube” recalled by a Reddit user suggests one course attempts a unique visual hook—perhaps a transparent tunnel submerged in an aquatic environment. But the overall aesthetic is described as “öde Parcours” (boring courses) by PC Action. There is no artistic cohesion, no sense of place, and no environmental storytelling. Courses are likely flat or simple ramps with minimal obstacles.

Visuals: 640×480 and Blocky Geometry

With a maximum resolution of 640×480, the game looks extremely pixelated even on the CRT monitors of its era. The graphics are not cartoony, nor are they realistic. They fall into an awkward middle ground: low‑poly 3D models (if 3D) or poorly rendered 2D sprites. Colors are likely washed out, textures non‑existent. Screenshots (not provided here but available on MobyGames) show barren landscapes, simple halfpipe structures, and a bland color palette. This visual poverty makes the game feel cheap and unfinished.

Sound: Sparse Effects, No Soundtrack

The only audio mentioned is sound effects. There is no indication of a musical soundtrack, let alone licensed punk or hip‑hop tracks that defined Tony Hawk. One can imagine a looping series of beeps, boops, and perhaps a basic drumbeat for the halfpipe. The lack of music contributes to the lifeless atmosphere; skateboarding games thrive on energetic audio to compensate for visual shortcomings. Here, the silence (or tinny sound effects) only amplifies the boredom.

Overall Contribution

The combination of low‑resolution graphics, generic environments, and sparse sound creates a world that is neither immersive nor charming. Unlike early arcade titles that used minimalist aesthetics to their advantage (e.g., 720°’s abstract style), Precision Skateboarding feels like a half‑baked prototype. It fails to transport the player anywhere, and the skateboarding action itself looks clumsy and unintuitive.

Reception & Legacy: A Critical and Commercial Black Hole

Critical Reception

Precision Skateboarding was almost universally panned by the few critics who encountered it. The sole listed critic review on MobyGames comes from PC Action (Germany), which awarded it a mere 13%. The review’s title, “Heiliges Skateboard – was ist denn das?” (“Holy skateboard – what is that?”), sets the tone. It mocks the “göttliche” (godly) 640×480 resolution, the boring courses that “even grandmas with their walkers could master,” and, above all, the “katastrophale Steuerung” (catastrophic controls). The verdict: “Absolut keine Konkurrenz zu Tony Hawk.” (“Absolutely no competition for Tony Hawk.”) This review succinctly captures the game’s complete inability to compete in a market dominated by a powerhouse franchise.

Player Reception: Nostalgia Mixed with Disdain

Player ratings on MobyGames average 3.1/5 from four users—a mediocre score that suggests some found value. However, the written commentary (though scarce) is telling. On Reddit, users who rediscovered the game years later expressed a mixture of horror and affection. bluespartians admitted: “what a terrible game it was, but my brother and I still played the shit out of it.” Another Redditor in r/GamePhysics simply noted buying it at a Scholastic Book Fair in 1999 (though the game’s actual release appears later). This phenomenon—the “so‑bad‑it’s‑good” attachment—is common among players who encountered such titles in childhood, often as their only available option. The game’s infuriating controls and simplicity may have fostered a perverse determination to master it, simply because there was nothing else. Yet, outside this niche nostalgia, Precision Skateboarding is generally reviled.

Commercial Performance and Availability

No sales figures are available, but the game’s distribution through Scholastic Book Fairs indicates it was a budget title, likely sold for under $10. It was not a mainstream retail product and would have been overshadowed by the Tony Hawk series on store shelves. Its presence on abandonware sites (MyAbandonware, Internet Archive) confirms that it is out of print and of no commercial value today. The fact that only a handful of players have rated it on MobyGames underscores its obscurity.

Legacy: A Cautionary Artifact

Precision Skateboarding has zero influence on the genre. It did not inspire mechanics, nor did it garner a sequel. Instead, it serves as a cautionary example of what happens when a developer underestimates the complexity of even a “simple” sports game. In the broader history of skateboarding video games—as chronicled by sources like Carbonated Thoughts and Everskate—Precision Skateboarding is a footnote, often omitted entirely. It represents the glut of low‑quality imitators that appeared in the early 2000s, attempting to cash in on the skating craze without the talent or resources to deliver a compelling product. For historians, it is a data point: a reminder that the dominance of Tony Hawk and later Skate was not uncontested; the market was flooded with junk, and Precision Skateboarding is a prime specimen.

Conclusion: The Price of “Precision”

Precision Skateboarding is, by any reasonable measure, a terrible video game. Its controls are unresponsive, its graphics are archaic, its content is threadbare, and its presentation is lifeless. It fails to deliver even a basic skateboarding experience, let alone a “precise” one. The game’s only saving grace is its rarity and the quirky, bittersweet memories it evokes in a tiny subset of players who, as children, spent hours wrestling with its broken mechanics because they had nothing better.

From a historical perspective, the game is a fascinating artifact of the early PC budget market. It demonstrates how the explosion of the skateboarding genre in the late 1990s and early 2000s attracted not only well‑funded studios but also fly‑by‑night operators hoping to grab a piece of the pie. Precision Skateboarding is the result of such ambition without craftsmanship. Its obscurity is a mercy; most gamers will never encounter it, and that is probably for the best.

Nevertheless, for the intrepid historian or the connoisseur of so‑bad‑it’s‑good gaming, Precision Skateboarding offers a grim reminder of an era when any publisher could slap a popular sport on a CD and ship it to discount bins. It stands as a testament to the importance of tight controls, meaningful progression, and authentic aesthetic—lessons the skateboarding genre would learn the hard way, through titles like this, while giants like Tony Hawk and later EA Skate pushed the medium forward.

Final Verdict: 1/10 – A forgotten relic of bargain‑bin shame, not recommended for anyone except archival researchers and the morbidly curious. Its place in video game history is that of a cautionary footnote, a ghost of skateboarding games past that never should have been.