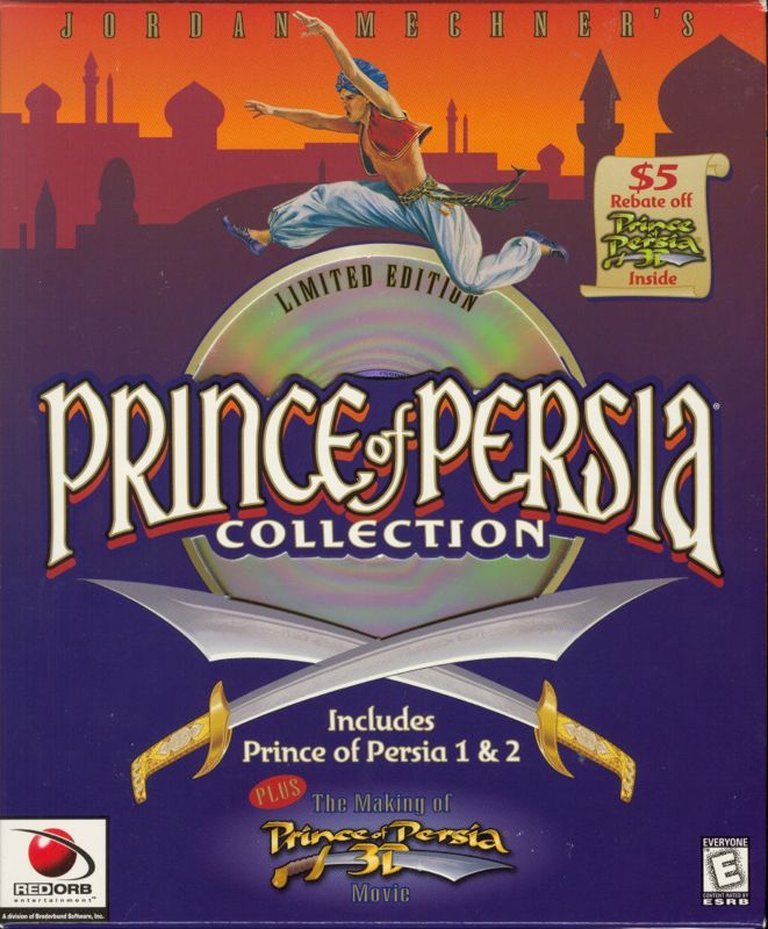

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: DOS, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Brøderbund Software, Inc.

- Developer: Brøderbund Software, Inc.

- Genre: Compilation

- Perspective: Side-scrolling

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Platforming, Swordfighting

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 66/100

Description

The Prince of Persia Collection compiles the groundbreaking cinematic platformers Prince of Persia (1989) and Prince of Persia 2: The Shadow & The Flame (1993), set in ancient Persia where players control a daring prince imprisoned by the evil Vizier Jaffar, who seeks to marry the sultan’s beautiful daughter; across both games, the hero navigates deadly dungeons filled with traps, solves intricate puzzles, engages in tense swordfights, and races against time to thwart Jaffar’s nefarious schemes and rescue his beloved.

Prince of Persia Collection Free Download

Prince of Persia Collection Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (60/100): PoP 1 – 7/10, PoP 2 – 5/10

mobygames.com (78/100): Two fantastic games on one CD

metacritic.com (60/100): PoP 1 – 7/10, PoP 2 – 5/10

Prince of Persia Collection Cheats & Codes

PC (Original)

Start the game with the “prince megahit” or “prince improved” command line (or “prince megahit X” where X is 2-14 to start on a specific level). Enter the following keys during gameplay.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| [Shift] + L | Level skip |

| [Shift] + I | Invert screen |

| [Shift] + T | Extra health point |

| [Shift] + K | Remove health point |

| [Shift] + B | Show only animated objects |

| [Shift] + S | Heal |

| [Shift] + R | Display room number, jump right |

| [Shift] + W | Display room number, jump left / Fall safely / Float down |

| [Alt] + D | Save debug information in “dump?.txt” file |

| U | View one screen up |

| N | View one screen down |

| H | View one screen left |

| J | View one screen right |

| K | Kill opponents |

| R | Resurrection |

| C | View code / Show coordinates |

| [F1] | Toggle position display |

| [F3] | Toggle player |

| [F6] | Ruler |

| [Plus] | Increase time |

| [Minus] | Decrease time |

| Shift + C | Display coordinates |

Prince of Persia Collection: Review

Introduction

In the late 1990s, as 3D graphics began dominating the gaming landscape with flashy polygons and booming soundtracks, Brøderbund Software dared to look backward—repackaging two pixel-perfect masterpieces from the Apple II era into the Prince of Persia Collection. Released in 1998 for Windows (with Macintosh and DOS ports following), this compilation bundled Jordan Mechner’s seminal 1989 Prince of Persia and its 1993 sequel Prince of Persia 2: The Shadow & The Flame, alongside a bonus making-of video for the ill-fated Prince of Persia 3D. What could have been a mere nostalgia cash-in instead stands as a time capsule of innovation, thrusting players into a world of rotoscoped fluidity, nail-biting tension, and cinematic platforming that predated—and profoundly influenced—modern action-adventures like Tomb Raider and Assassin’s Creed. My thesis: This collection isn’t just a preservation effort; it’s a masterclass in how technological constraints birthed timeless design, cementing the Prince’s legacy as gaming’s original acrobatic icon, essential for historians, retro enthusiasts, and newcomers alike.

Development History & Context

The Prince of Persia Collection arrived at a pivotal juncture in gaming history, bridging the 16-bit/early CD-ROM era with the looming 3D revolution. Brøderbund Software, Inc.—publishers and developers of the compilation—had shepherded the franchise since its inception. Jordan Mechner, a 25-year-old NYU film student turned prodigy, created the original Prince of Persia after the success of his 1984 Apple II hit Karateka. Funded by Karateka‘s profits, Mechner spent over two years on the Apple II, battling its paltry 48KB memory limit. He pioneered rotoscoping: filming his brother David performing leaps, climbs, and swordfights (inspired by Errol Flynn’s Robin Hood), then tracing frames onto video for hyper-realistic animations. This technique, born from Karateka‘s family-filmed martial arts sequences, squeezed dozens of fluid actions into constrained RAM using clever tricks like the Apple II’s EOR (Exclusive-OR) command to generate the “Shadow Man” enemy—a memory-efficient doppelganger that “XORed” the Prince’s sprite against itself.

Prince of Persia 2: The Shadow & The Flame (1993) expanded this under Mechner’s supervision at Broderbund, introducing potions, more enemies, and shipwreck escapes, but retained the 2D side-scrolling core. By 1998, Broderbund was faltering amid corporate upheavals—The Learning Company acquired it in 1998, then Mattel, before Ubisoft snatched the IP in 2001. The collection targeted PC users craving roots amid hype for Prince of Persia 3D (1999, developed by Red Orb Entertainment), including a 12-minute “making-of” video teasing that buggy 3D misstep. Technological constraints defined the era: Apple II’s decline forced ports to DOS, Amiga, and consoles, making Prince of Persia one of gaming’s most ported titles (over 20 versions). In a landscape dominated by Doom‘s frenetic shooters and Myst‘s slow-burn puzzles, this compilation reminded players of platforming’s pure, deliberate joy—prefiguring Ubisoft’s Sands of Time reboot.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its heart, the Prince of Persia Collection weaves Arabian Nights-inspired tales of heroism, betrayal, and resurrection, distilled into taut, 60-minute epics that prioritize urgency over sprawl. The original Prince of Persia (1989) opens with a fairy-tale hook: an unnamed orphan Prince, smitten with the Princess, is hurled into the Sultan’s dungeon by the power-hungry Vizier Jaffar. With one hour ticking (real-time, extendable via potions), the Prince navigates traps, guards, and a skeletal “Shadow Man” mirror duplicate to confront Jaffar atop his throne. Themes of love conquering tyranny resonate deeply—Jaffar’s defeat yields a tender kiss amid crumbling palace walls—but subtle horror lurks: spikes impale, blades slice, and death resets with a ghostly yelp, evoking mortality’s sting.

Prince of Persia 2 picks up mere days later, subverting expectations. Cursed into a stranger’s form by Jaffar (resurrected via dark magic), the Prince flees a palace that now hunts him as an assassin. Shipwrecks lead to potion-brewing quests, demon fights, and a climactic potion-fueled immolation of the Vizier. Dialogue is sparse—silhouetted cutscenes and environmental storytelling heighten isolation—but themes deepen: identity loss (the “shadow” curse mirroring the first game’s foe), redemption, and cyclical evil. The Princess evolves from damsel to ally, hinting at agency absent in many contemporaries. Underlying motifs draw from Mechner’s inspirations (One Thousand and One Nights, Raiders of the Lost Ark): fate vs. free will (time limit as inexorable doom), the hero’s isolation in opulent yet lethal palaces, and resurrection as double-edged sorcery. These narratives, economical yet evocative, influenced later tales like The Sands of Time‘s time-manipulating hubris, proving 2D constraints fostered profound thematic density.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The collection’s brilliance lies in deceptively simple loops that demand pixel-perfect mastery, blending platforming, combat, and light puzzles into addictive peril. Core to both games: fluid movement—run, jump (variable length/height), climb ledges, hang/drop, crouch/crawl. Prince of Persia 1‘s 12-level dungeon gauntlet enforces deliberate pacing: momentum matters, mistimed leaps plummet to spikes or crushers. Combat introduces swordplay—parry-thrust combos against four guards (fat, skeleton, swordmaster, beast)—culminating in tense boss duels. The genius Shadow Man fight merges with the Prince via sword sheath, rewarding avoidance over aggression. Potions extend the hourglass; no saves mean death’s sting is real, fostering replayability.

PoP 2 iterates masterfully: longer (four hours), with 44 levels across palace, ship, and ruins. New mechanics—shadow-disguise infiltration, bomb-throwing, loose-floor tiles, kid allies—add variety. Combat expands (more foes, combos), but difficulty spikes notoriously (player review: “just too difficult but give it the time”). UI is minimalist: health bar (four pots), timer, potion counter—no maps, forcing environmental memory. Flaws persist: clunky keyboard controls (mouse optional), no mid-level saves, era-specific sound glitches on modern PCs. Yet innovations shine—EOR-generated enemies halved memory use, enabling denser traps. Loops evolve from escape (PoP1) to revenge odyssey (PoP2), pioneering “cinematic platformers” where animation drives interaction, predating Flashback or Another World.

| Mechanic | PoP 1 | PoP 2 | Innovation/Flaw |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platforming | Basic jumps, climbs | Adds rolls, wall-runs | Fluid rotoscoping; precise but unforgiving |

| Combat | 1v1 swordfights | Multi-enemy, potions | Tense, animation-locked; dated AI |

| Puzzles | Trap navigation | Bomb/infiltration | Contextual, no hand-holding |

| Progression | Linear levels, timer | Expansive worlds | No RPG; skill-based mastery |

| UI/Controls | Keyboard primacy | Mouse support | Archaic; bonus video unplayable on some rigs |

World-Building, Art & Sound

Settings evoke mythical Persia: torch-lit dungeons, collapsing palaces, storm-tossed ships—labyrinthine yet intimate, fostering claustrophobic dread. Art direction is revolutionary: rotoscoped sprites yield balletic realism (24 frames per leap vs. contemporaries’ 4-8), with silhouetted vistas (tower climbs, sunsets) masking hardware limits for cinematic flair. PoP1‘s monochrome Apple II roots ported gorgeously to VGA; PoP2 adds color palettes, bubbling potions, fiery effects. Critic Electric Games noted “dated graphics,” but this belies timeless elegance—shadows flicker authentically, guards lumber with weight.

Sound design punches above 8-bit weight: Francis Mechner’s piano score (reused from Karateka) swells dramatically—haunting arpeggios for tension, triumphant motifs post-boss. SFX via PC speaker (beeps for jumps, screams for death) grate modern ears but amplified urgency in 1989. No voice acting; environmental audio (dripping water, blade whirs) builds immersion. Together, these craft atmosphere of ancient peril: opulent tiles hide spikes, mirroring folklore’s deceptive beauty. The bonus PoP3D video adds meta-layer, previewing 3D pitfalls amid 2D purity.

Reception & Legacy

Launch reception was solid but polarized: MobyGames aggregates 72% critics (World Village: 100%, lauding “plenty of jumping… swordfighting”; Electric Games: 50%, slamming “dated graphics… internal speaker?”). Players averaged 4.6/5, with Djinn’s DOS review hailing “two fantastic games… for new kids.” Commercial success was modest—$19.95 MSRP bundled classics plus $5 PoP3D coupon—but preservation value soared. Reputation evolved: post-Ubisoft reboot (Sands of Time, 2003), retro waves (GOG ports) hailed it as foundational.

Influence is seismic: rotoscoping begat Out of This World; platforming loops shaped Tomb Raider (evocative feel admitted by devs); Assassin’s Creed spun from Sands prototypes, inheriting parkour/time-rewind. Guinness records (first motion-capture in games) underscore impact. PoP3D‘s flop contrasted, but collection endures—33 MobyGames collectors, academic citations. It influenced mobile remakes (Classic, 2007) and Lost Crown (2024 Metroidvania revival).

Conclusion

The Prince of Persia Collection transcends compilation status, enshrining Mechner’s miracles amid Apple II austerity as gaming’s blueprint for cinematic action. Flaws—dated tech, PoP2‘s brutality—pale against innovations in animation, tension, and themes of defiant love. With 7.8 MobyScore holding firm, it’s not flawless (6/10 modern lens), but irreplaceable: 10/10 historical artifact. In video game history, it claims pioneering status—play it to grasp why a leaping silhouette birthed parkour empires. Essential for all; a definitive must-own preserving the Prince’s golden age.