- Release Year: 1984

- Platforms: Atari 2600, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Activision, Inc., Microsoft Corporation

- Developer: Activision, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Vehicular

- Setting: City – New York, Interwar, North America

- Average Score: 64/100

Description

In ‘Private Eye’, you play as Pierre Touche, a French private investigator tasked with capturing the criminal Henri Le Fiend. Drive around a city, collect evidence, and return stolen items while navigating obstacles and dangerous characters. The game features five cases, each with unique goals and time limits, set in different parts of the city. With varying difficulty settings and a side-scrolling perspective, ‘Private Eye’ offers a mix of action and mystery.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Private Eye

PC

Private Eye Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com : You are the great French private eye Pierre Touche. Your job is to capture the criminal Henri Le Fiend and send him to jail.

uvlist.net (64.3/100): Allow me to introduce myself. I am the great French Inspector Pierre Touché. And you? Well, enough with the formalities. Frankly, I need your help.

Private Eye Cheats & Codes

NEC PC Engine CD-ROM2 / Turbo CD

Enter codes at specific screens (CD boot screen, title screen, or main menu) as described below.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| Hold I while loading > Up, Down, Left, Right, Up, Down, Select, II at title screen | Activates interactive debug mode |

| Hold I + Run during CD boot > Hold Right + Select at main menu > Select ‘Begin’ | Enables Omake mode |

| Hold I + Run during CD boot > Hold Up + Select at main menu > Select ‘Begin’ | Starts game at Scenario 2 |

| Hold I + Run during CD boot > Hold Down + Select at main menu > Select ‘Begin’ | Starts game at Scenario 3 |

| Hold I + Run during CD boot > Hold Left + Select at main menu > Select ‘Begin’ | Starts game at Scenario 4 |

Private Eye: Review

Introduction

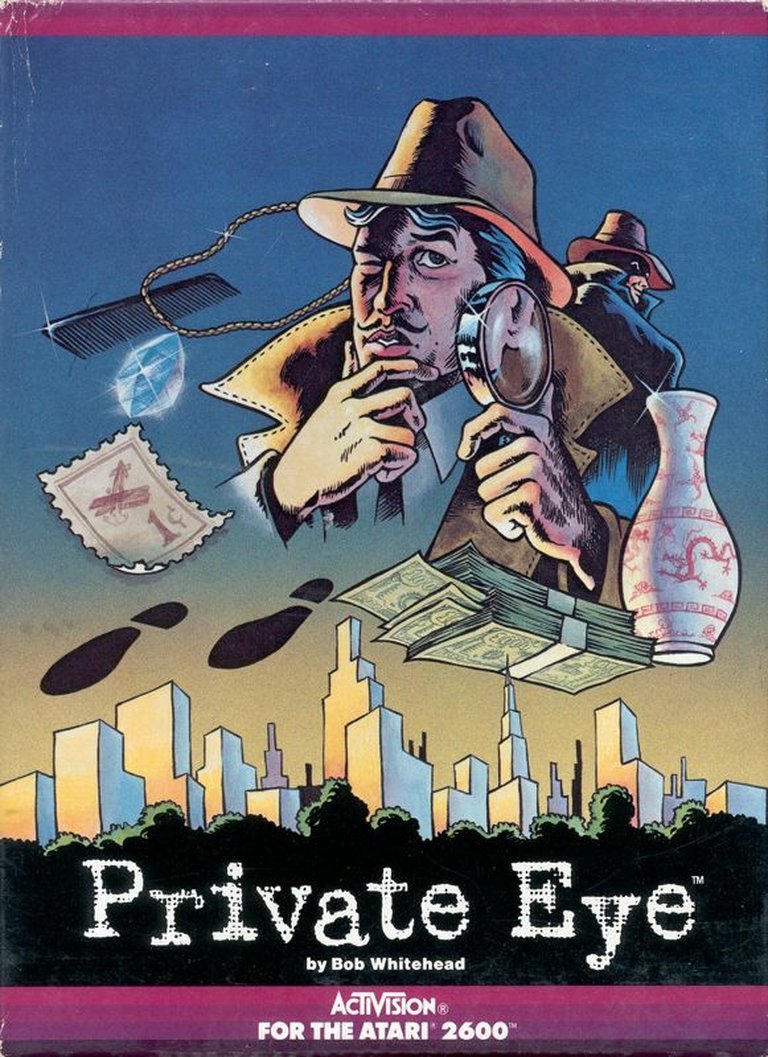

In the pantheon of Atari 2600 classics, Private Eye (1984) lingers as a curious outlier—a detective-themed action-adventure that dared to blend exploratory mystery with arcade-style chaos. Developed by Activision at the height of the console’s dominance, the game casts players as the dashing French sleuth Pierre Touche, tasked with apprehending the villainous Henri Le Fiend across five increasingly complex cases. While overshadowed by Activision’s marquee titles like Pitfall! and River Raid, Private Eye remains a fascinating artifact of ambition amid the Atari’s technical constraints. This review unpacks its legacy: a flawed but inventive experiment that straddled genres years before “open-world” became a buzzword.

Development History & Context

Creators & Vision

Private Eye was crafted by Bob Whitehead, a veteran programmer whose credits included Chopper Command and Star Master. Whitehead sought to expand the Atari 2600’s repertoire beyond pure action games, envisioning a hybrid experience that merged exploration, item collection, and timed objectives. Activision, then a powerhouse of Atari development, greenlit the project as part of its strategy to diversify its catalog with narrative-driven games.

Technological Constraints

The Atari 2600’s 128 bytes of RAM and lack of scrolling forced Whitehead to innovate. The game’s city is divided into 248 static screens (or “blocks”), navigated via a jump-capable Model A car. To simulate a sprawling environment, Whitehead employed pseudo-randomized roadblocks and secret passages, encouraging players to mentally map their routes—a crude precursor to modern Metroidvania design.

Gaming Landscape

Private Eye debuted during the post-crash lull of 1984, a time when players craved depth amid a sea of shallow arcade ports. While critics praised its ambition, its complexity alienated some audiences. Compared to contemporaries like Pitfall!, which focused on tight platforming, Private Eye asked players to juggle navigation, puzzle-solving, and combat—a risky gambit for an era defined by instant gratification.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot & Characters

The premise is pulp simplicity: the suave Pierre Touche must recover stolen goods (a necklace, gun, vase, etc.) and evidence to arrest Henri Le Fiend, a cartoonish master thief. Each of the five cases—Safecracker Suite, Dealing in Diamonds, The Big Sweep, and others—escalates in scope, mirroring the structure of a detective serial. Dialogue is nonexistent, but the game’s manual fleshes out Pierre’s persona as a “great French Inspector,” leaning into noir tropes with a tongue-in-cheek tone.

Themes

Beneath its cheerful veneer, Private Eye explores themes of order versus chaos. The orderly grid of the city is disrupted by Le Fiend’s crimes, and players must restore balance by returning items to their rightful places (e.g., a vase to the museum). The timer—a “statute of limitations”—adds urgency, evoking the pressure of real detective work.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop

The gameplay revolves around three tasks per case:

1. Find a clue (e.g., a receipt) and verify it at a relevant business.

2. Recover a stolen item and return it to its owner.

3. Capture Le Fiend and deliver him to the police station.

Players navigate the city in a jump-enabled car, dodging flower pots, daggers, and potholes while hunting for “questionable characters” (thugs in windows) who hold key items. Carrying only one object at a time heightens tension; losing an item to an attack means backtracking.

Innovations & Flaws

- Jumping Mechanic: The car’s jump (triggered by the fire button) allows evasion and access to upper-story windows, a novel trick for the era.

- Dynamic Obstacles: Roadblocks and one-way streets change between cases, forcing adaptability.

- Frustrations: The lack of in-game maps and reliance on trial-and-error drew criticism. As The Video Game Critic noted, “It’s too easy to get lost.”

UI & Progression

A top-down dashboard shows held items, timer, and “merit points” (lost for collisions). Points reward exploration but add little beyond bragging rights. The five cases act as difficulty tiers, with later levels spanning up to 248 screens.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design

Activision’s signature polish shines in Private Eye’s vibrant, cartoonish sprites. The city blocks feature distinct buildings (museums, gem stores) with pixel-art charm, while Pierre’s bouncing car exudes personality. Critics lauded its clarity amid the Atari’s technical limits.

Atmosphere

The game channels a 1930s noir-lite vibe, with New York-inspired streets and jazzy, if rudimentary, sound effects. The lack of music heightens the isolation of detective work, though some found the silence underwhelming.

Sound Design

Bleeps denote jumps and collisions, while a siren-like wail accompanies Le Fiend’s appearance. It’s functional but unremarkable—a missed opportunity to deepen immersion.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Reception

Private Eye earned mixed reviews:

– Power Play (60/100) called it a “willkommene Abwechslung” (welcome change) from space shooters but lamented its repetitive endgame.

– Woodgrain Wonderland (42/100) praised its visuals but deemed the action elements “silly.”

– The Video Game Critic (33/100) skewered its opaque design: “Requires too much trial and error.”

Player ratings averaged 3.3/5, reflecting niche appeal.

Commercial Performance

The game sold modestly, drowned out by Activision’s flashier titles. However, dedicated fans could mail high-score proofs for a “Super Sleuth” patch—a clever marketing tactic.

Legacy

Private Eye’s influence is subtle but lasting. Its fusion of action and adventure presaged later hybrids like Zelda II, while its urban exploration hinted at open-world design. Inclusion in Activision Anthology (2002) revived interest, cementing its cult status.

Conclusion

Private Eye is a relic of daring design—a game too ambitious for its hardware yet too unwieldy for mass appeal. While its labyrinthine streets and trial-and-error gameplay test modern patience, its creativity commands respect. For historians, it’s a window into an era when developers stretched the Atari 2600 to its limits; for players, it remains a quirky, flawed gem. In the annals of gaming history, Private Eye isn’t a masterpiece, but it’s undeniably a visionary oddity—a detective story worth solving, if only once.