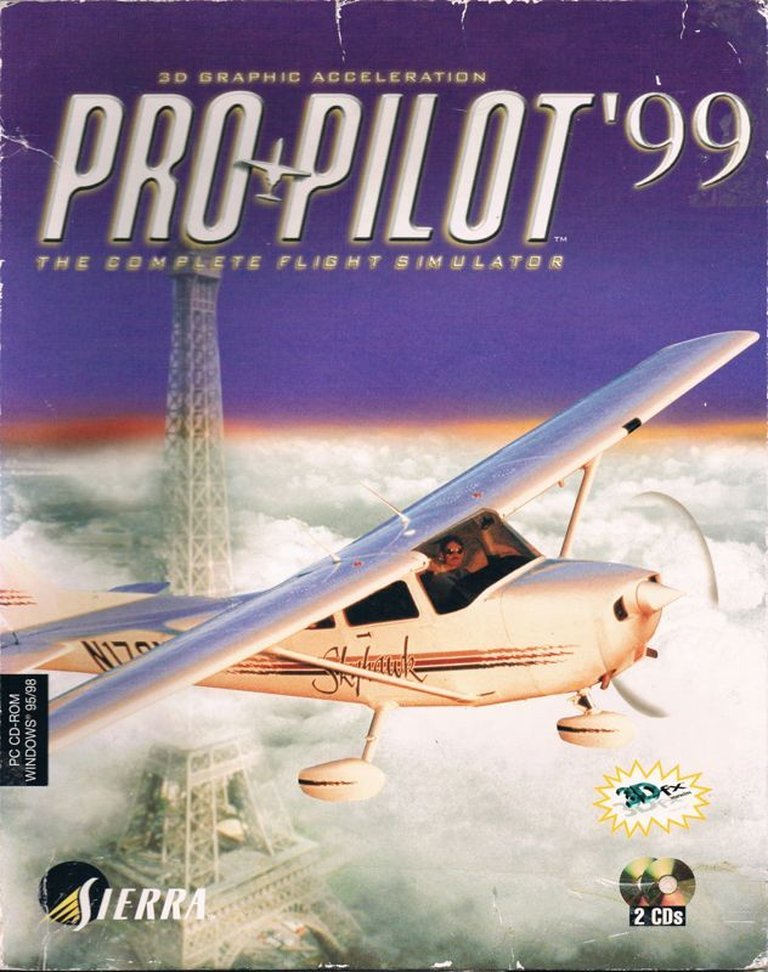

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Acer TWP Corp, Imagineer Co., Ltd., Sierra On-Line, Inc.

- Developer: Dynamix, Inc.

- Genre: Simulation

- Perspective: 1st-person, 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Navigation, Realistic flight simulation, Training missions

- Setting: USA, Western Europe

- Average Score: 58/100

Description

Pro Pilot ’99 is a realistic flight simulation game emphasizing authentic flight operations over arcade gameplay. It features six aircraft and detailed scenery for the USA and Western Europe, using a technical GPS system for navigation. Developed in cooperation with the National Association of Flight Instructors, it includes an in-depth operations manual, instructional videos, and training courses to educate users on real-world flying procedures and aircraft systems.

Gameplay Videos

Pro Pilot ’99 Free Download

PC

Pro Pilot ’99 Patches & Updates

Pro Pilot ’99 Reviews & Reception

ign.com (58/100): The industry’s latest boxed patch makes a handful of improvements — but it’s too little, too late.

gamegenie.com : Pro Pilot ’99 is really a game for people who know what they are doing.

Pro Pilot ’99: As Real As It Gets—A Modern Historical Reappraisal

Introduction: The Last Serious Stand

In the annals of PC flight simulation, 1998 stands as a pivotal year. Microsoft’s Flight Simulator 98 dominated the mainstream with its accessible polish, while Flight Unlimited II captivated with its visceral, arcade-adjacent feel. Into this landscape stepped Sierra’s Pro Pilot ’99, a title that defiantly rejected the “game” in flight simulation. Developed by the veteran studio Dynamix and created in direct consultation with the National Association of Flight Instructors (NAFI), it was less a product and more a digital textbook—a rigid, uncompromising tool designed not for entertainment, but for pedagogy. Its legacy is not one of blockbuster sales or genre-defining innovation, but of a fascinating, flawed, and ultimately pure artifact of an era when simulation meant simulation, and the skies were for students, not dreamers. This review argues that Pro Pilot ’99 is a critical historical document: the final, formidable stand of the hyper-realistic, training-first civilian flight sim before the genre’s inexorable shift toward accessibility and entertainment.

Development History & Context: Dynamix’s Swan Song for Serious Skies

The Studio and the Vision: Dynamix, Inc., the developer behind classics like Red Baron and A-10 Tank Killer, had a pedigree in hardcore combat simulations. With the Pro Pilot series, they pivoted sharply to civilian aviation, seeking to carve a niche distinct from the juggernaut of Microsoft Flight Simulator. The stated vision was audacious: to create a simulator so procedurally authentic it could serve as a legitimate instrument for flight training. The partnership with NAFI was not a marketing footnote; it was the project’s bedrock. This collaboration ensured that checklists, radio procedures, navigation protocols, and aircraft systems behavior mirrored real-world Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) standards.

Technological Constraints and Choices: The year 1998 was the cusp of 3D acceleration. Pro Pilot ’99’s most publicized feature was its support for 3dfx Voodoo cards—a clear response to the graphical leap taken by Flight Unlimited II. However, this support felt tacked on. The core engine was fundamentally a software renderer, and the 3dfx patch often resulted in the infamous “rubble texture” effect where distant scenery became a blocky, shifting mess, as noted by critics from PC Action and PC Joker. This technical debt stemmed from a choice: resources were poured into cockpit fidelity, flight model physics, and systems depth, not into a scalable, modern graphics pipeline. The requirement for frequent CD-ROM access, criticized by GameGenie, further hampered performance on contemporary hardware, making the sim a study in trade-offs.

The Gaming Landscape: This was the height of the “Sim Boom,” but also the beginning of its decline. Microsoft Flight Simulator 98 had set the standard for combining realism with user-friendliness and, crucially, an immense ecosystem of add-ons. Flight Unlimited II offered stunning visual realism and passive atmospheric flight. Pro Pilot ’99 entered this ring not as a competitor in fun or beauty, but as a purist’s alternative. It was the anti-FS98: where Microsoft provided a friendly “hand-holding” experience, Pro Pilot demanded pre-existing knowledge or intense commitment to its included “operations manual” and video courses. Its world was a smaller, more technically precise subset of the globe (USA and Western Europe), built not for sightseeing but for practicing instrument approaches and air traffic control (ATC) protocols.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story Is the Checklist

Pro Pilot ’99 possesses no narrative in the traditional sense. There is no campaign, no storyline, no protagonist. Its “narrative” is the procedural story of a flight, from pre-departure planning through startup, taxi, takeoff, en-route navigation, approach, and landing. The theme is singular: Procedural Authenticity as Catharsis. The drama is not in saving the world, but in successfully tuning a VOR frequency, interpreting a HSI display, and executing a missed approach after a simulated engine failure.

The “characters” are the systems themselves: the Cessna 172’s forgiving but honest flight model, the brittle responsiveness of the CitationJet at low speeds, the unblinking eyes of the ATC controllers whose dynamic radio chatter (GameGenie‘s “incredible feature”) injects a breathtaking sense of operational reality. The “dialogue” is the terse, procedural talk between pilot and controller, a linguistic challenge for the uninitiated. The underlying theme is mastery through rigidity. The game does not reward creativity within its systems; it rewards exact adherence. This makes it a fascinating contrast to the gamified, objective-based simulations of its era. Its purpose was not to tell a story, but to teach a language—the language of the skies.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Cockpit as Cathedral

Core Loop & Philosophy: The loop is: Plan → Prepare → Execute → Debrief. A player begins at the Operations Desk, selecting an aircraft (six in total: Cessna 172 Skyhawks, Beechcraft Bonanza, Baron B58, Super King Air B200, CitationJet 525—a solid mix of trainers and light jets), a departure airport, a destination, and crucially, a flight plan. This is not a casual click; it’s a study in IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) planning, requiring understanding of airways, navaids, and altitudes.

Systems Depth: The brilliance and barrier to entry reside in the cockpit. Unlike Flight Simulator 98, whose panels were often criticized for “dummy” gauges, every switch, knob, and dial in Pro Pilot ’99 is functional. Trimming the elevator, managing fuel mixtures, understanding the nuances of the dual COMM/NAV radios, and interpreting the integrated GPS display (a technical, non-visual map system) are not optional. The flight models are, by contemporary accounts, “very realistic” (GameGenie) and “excellent” (Gamesmania.de), though PC Games (Germany) famously lambasted them for being incapable of performing basic aerobatics like loops or stable inverted flight—a deliberate design choice prioritizing general aviation stability over aerobatic capability, misunderstood by the critic as a flaw.

Innovations and Flaws: The pioneering dynamic ATC system was a monumental achievement. Controllers issued instructions, sequenced arrivals and departures, and created a living airspace. However, its implementation was buggy; the radio chatter was “choppy” (GameGenie) and the AI logic could be inconsistent. The in-game “Operations Manual” and video training courses were genuinely excellent educational tools, a feature few contemporaries matched. The fatal flaws were peripheral: the crippling CD-access stutter, the lack of a 3D map view for flight planning (a point of frustration for PC Player), and a nearly non-existent modding scene or third-party add-on support compared to the vibrant FS ecosystem. As GameSpot astutely noted, it was superb for “practicing instrument navigation,” but lacked the “photo-realistic scenery” push and expandable aircraft library for the sightseeing enthusiast.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Study in Functional Atmosphere

Visuals: Pro Pilot ’99 is a game of two graphical eras. The cockpit interiors are masterclasses in functional art. Photorealistic textures, 3D-modeled moving parts (rudder pedals, yoke, throttle quadrant), and meticulous attention to gauge detail created an immersive, believable space. This was praised universally. The external world, however, was a different story. Scenery was based on low-resolution satellite data. With hardware acceleration enabled on a 3Dfx card, textures became smoother and clouds gained a “transparent, organic” quality praised by Power Play as worthy of an “Oscar.” But without it, or at higher altitudes, the landscape became a blurry, repetitive quilt. PC Joker called the textures “extremely ugly.” The art direction prioritized geographic accuracy and functional airport layouts (over 4,300 in the US/Europe database) over aesthetic beauty. Cities were blocky collections of buildings; the terrain lacked the lush, hand-crafted detail of Flight Unlimited II.

Soundscape: This is where the simulation truly sang. The sound design was exceptional. Engine noises changed with RPM and attitude. Wind sounds varied with airspeed. The boot-up sequences of different aircraft were audible lessons in themselves. But the crown jewel was the ATC and cockpit audio. The dynamic radio chatter, despite its choppiness, delivered an unmatched sense of being part of a controlled system. The clarity and professionalism of the voice acting for ATC (in its original English) lent immense credibility. For the serious student, this audio environment was not just atmospheric; it was instructional.

Atmosphere & Contribution: The combined effect was not one of awe at a beautiful world, but of awe at a functional world. The atmosphere was one of quiet, intense concentration. The world-building served the simulation’s primary goal: to make you feel like a pilot, not a tourist. The lack of cinematic flair was, in this context, a virtue. The experience was mediated entirely through the cockpit instruments and radio, a profoundly first-person, professional perspective rarely matched since.

Reception & Legacy: The Critical Divide and the Niche’s Endurance

Contemporary Reception: The critical spectrum was impossibly wide, from Power Play‘s ecstatic 89% (“a ‘full hit’”) to Jeuxvideo.com‘s scathing 45% (“a botched job”). This divide maps perfectly onto the “simmer vs. gamer” schism.

* The Purist Praise: Reviews from Gamezilla (87%), Power Unlimited (84%), and Gamesmania.de (75%) celebrated its unparalleled realism, cockpits, and training value. CGW gave it an extra half-star for its “outstanding, comprehensive flight instruction,” calling it usable where its predecessor was not.

* The Gamer Critique: Mainstream and visually-focused outlets panned it. IGN (58%) saw it as a “game of catch-up” that couldn’t compete with FS98 or upcoming titles. German magazines like PC Action (55%) and PC Games (52%) were particularly harsh on the graphics engine and lack of adventure missions. The common complaint: it was “too complicated” (Power Unlimited‘s succinct verdict for gamers) and a mere “patch” (GameStar) rather than a full sequel.

Commercial Performance & Fate: The Wikipedia-sourced sales figure of >275,000 units for the original Sierra Pro Pilot and its high chart placement (PC Data‘s #17 for Feb 1998) indicate solid, if not spectacular, commercial success for a niche title. However, the series did not endure. The Pro Pilot line faded after Pro Pilot USA (1998) and Pro Pilot 2000. Dynamix closed its doors in 2001. The vision of a NAFI-certified consumer simulator was subsumed by the overwhelming scalability and third-party support of the Microsoft Flight Simulator franchise and later, the X-Plane series with its plugin architecture. Pro Pilot ’99 represents a dead-end branch in the evolutionary tree of flight sims.

Evolving Legacy: Today, its reputation exists in a fascinating limbo. It is not remembered as a classic. It is not cited as an influence on major franchises. Its legacy is archival and pedagogical. Abandonware sites host it, and the user comments on sites like My Abandonware reveal its true impact: “I used it to help teach my IFR students… Still flying with it and I am 90 years old.” (flyboyjd, 2025) and “One of the best Pilot training softwares, this simulator made me an actual pilot in RL.” (Helldiver, 2022). For a small cohort of real-world pilots and instructors, Pro Pilot ’99 was not a game; it was a cheap, effective, and surprisingly accurate training supplement. Its legacy is that of a specialized tool that succeeded in its hyper-specific mission, even as it failed to find a broader audience.

Conclusion: A Flawed Masterpiece of Pedagogy

Pro Pilot ’99 is not a great game. By any standard of engagement, fun, graphical fidelity, or long-term support, it is outclassed by its contemporaries and successors. It is riddled with technical compromises—the CD stutter, the inconsistent graphics, the barren modding scene.

However, as an artifact of design philosophy, it is utterly remarkable and historically significant. It is the most uncompromisingly serious, NAFI-vetted civilian flight simulation ever mass-marketed to consumers. It prioritized the functional integrity of a cockpit and the procedural correctness of an ATC exchange over the beauty of a sunset over the Alps. In an industry increasingly oriented toward “play,” Pro Pilot ’99 stood firmly for “practice.”

Its final verdict must be bifurcated. For the gamer seeking the thrill of flight or the beauty of a virtual world, it is a dated, frustrating, and visually underwhelming relic, score: 58/100. For the student pilot, aviation enthusiast, or historian of simulation, it is a invaluable, authentic time capsule—a sometimes-broken but often brilliant window into a specific moment when software aspired to be a textbook, score: 85/100.

In the pantheon of flight sims, Pro Pilot ’99 is not a king. It is the stern, demanding, and brilliant professor whom everyone remembers, even if they dreaded his class. Its place in history is secured not by its success, but by the purity and specificity of its ambition—a final, formidable salute from an era that believed the virtual skies should be governed by the same rules as the real ones.