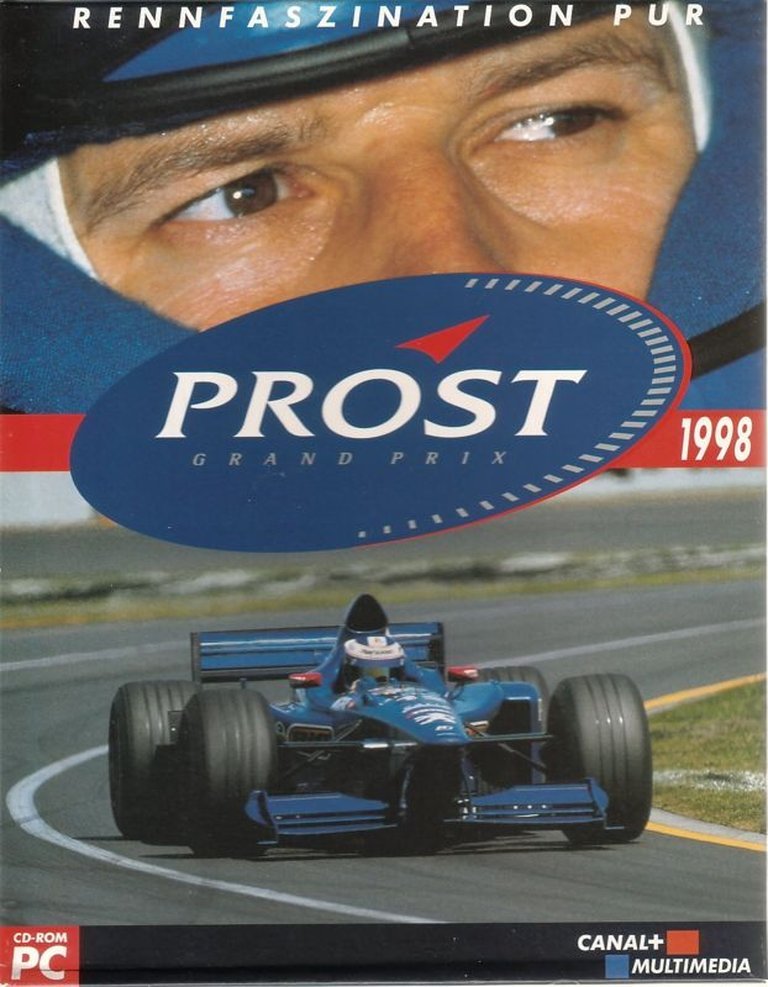

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: DOS, Windows

- Publisher: Canal+Multimédia

- Developer: Visiware

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: 1st-person, 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: LAN, Single-player

- Gameplay: Track racing, Vehicle simulation

- Setting: Oceania

- Average Score: 74/100

Description

Prost Grand Prix 1998 is a Formula One racing simulation game endorsed by the Prost Grand Prix team owned by four-time World Champion Alain Prost, featuring all teams and drivers from the 1997 F1 season. While only the PGP team is officially licensed, players can customize other teams, cars, and circuits to match their real-world counterparts, including editing names, colors, performance, and reliability; the game offers modes like full championships, single races, private testing sessions, and adjustable driver aids for varying levels of realism, set against global F1 tracks such as those in Australia, Brazil, and France.

Gameplay Videos

Prost Grand Prix 1998 Free Download

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

unracedf1.com : A nice attempt with its own little charm, but lacking real racing feeling.

Prost Grand Prix 1998: Review

Introduction

Imagine revving up an engine on the grid at Melbourne’s Albert Park, the roar of V10s echoing as Alain Prost’s namesake team vies for glory in a digital recreation of Formula 1’s high-stakes world. Released in 1998, Prost Grand Prix 1998—often simply called PGP—arrived as a licensed tribute to the legendary French driver’s eponymous racing outfit, capturing a pivotal moment when Prost transitioned from four-time world champion to team principal. In an era dominated by blistering simulations like Psygnosis’ F1 ’97, this Visiware-developed title promised accessible F1 action with a distinctly French flair, endorsed by the Prost Grand Prix team that had risen from the ashes of the bankrupt Ligier squad. Yet, its legacy is one of unfulfilled potential: a budget-friendly entry that charmed casual fans but stumbled under the weight of technical shortcomings. This review argues that while Prost Grand Prix 1998 endures as a nostalgic artifact of late-90s motorsport gaming—evoking the thrill of editable rosters and season-long campaigns—its outdated mechanics and visual austerity prevent it from claiming a podium spot in F1 simulation history.

Development History & Context

Developed by the Paris-based studio Visiware and published by Canal+Multimédia—a French media giant with deep ties to motorsport broadcasting—the game emerged from a vision to promote Alain Prost’s ambitious new venture. Prost, who retired from driving in 1993 after clinching his fourth title, acquired the Ligier team in 1997, rebranding it Prost Grand Prix (PGP) for the 1998 season. Visiware, known for modest titles like adventure games and early 3D experiments, saw PGP as an opportunity to blend simulation with accessibility, leveraging Prost’s endorsement to infuse the project with authentic F1 pedigree. Key figures included executive producers Alain Le Diberder and Laurant Weill, development director Mark Greenshields (who doubled as producer), and a core programming team led by Laurent Lichnewsky, alongside graphics specialists like Philippe Malbrunot and 3D artists Antony Templier and Paolo Menegotto. The soundtrack fell to La Marque Rose, emphasizing the French-centric production.

Technological constraints of 1998 defined the game’s scope. Running on DOS and early Windows (requiring Pentium 100 MHz and 16MB RAM), it eschewed cutting-edge engines for a custom 3D framework that supported optional accelerators like 3Dfx Voodoo—though implementation was rudimentary, with critics lamenting “lächerlich” (ridiculous) textures even on high-end hardware. Development reportedly dragged on, with early plans surfacing in 1997, leading to a release that felt “one or two years behind” contemporaries. The gaming landscape was fiercely competitive: Accolade’s Grand Prix Legends (1998) set a realism benchmark with its physics model, while Psygnosis’ F1 ’97 offered polished arcade-simulation hybrid on PlayStation. PC racers grappled with the shift to 3D acceleration, but PGP prioritized low system demands over visual fidelity, positioning itself as an affordable alternative (priced at around 59 DM, or roughly $30 USD) for budget-conscious Europeans. Canal+’s involvement ensured a focus on the 1997 F1 season’s teams and tracks, though lacking full FIA licensing forced editable placeholders for non-Prost elements—a clever workaround reflecting the era’s licensing hurdles amid booming F1 popularity post-Senna.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

As a pure racing simulation, Prost Grand Prix 1998 eschews traditional narrative arcs for the procedural drama of a Formula 1 season, where “story” unfolds through emergent competition rather than scripted plot. The game’s core “narrative” revolves around embodying Olivier Panis or Jarno Trulli in the Prost AP02, navigating a 17-race championship that mirrors the 1997 calendar—from Australia’s sun-baked opener to Japan’s rain-soaked finale. Without voiced cutscenes or dialogue, the experience is driven by menu-driven exposition: pre-race briefings detail track layouts, weather forecasts (sunny, cloudy, or rainy), and rival lineups, fostering a sense of progression as you climb the constructors’ standings. Characters are reduced to editable archetypes—fictitious drivers like “J. Heldenview” (a playful nod to real-world figures) or “Pedro Pinze” in the “Gieger” team—allowing players to restore authenticity by renaming them to Michael Schumacher or Damon Hill, complete with adjustable skill ratings for speed and reliability.

Thematically, PGP delves into Prost’s real-life ethos of calculated precision over raw aggression, embodying themes of redemption and underdog resilience. The Prost team, starting from Ligier’s ruins, symbolized a fresh start in F1’s cutthroat ecosystem, and the game mirrors this through its emphasis on setup tweaks (spoilers, tires, gear ratios) and penalty systems like “stop & go” or disqualification, enforcing FIA realism. Underlying motifs include national pride—French sponsors dominate visuals, and the AP02’s livery gleams as a patriotic beacon—and the democratization of F1, where editing tools let players rewrite history, turning PGP into a modder’s canvas. Dialogue is absent, but in-game text (e.g., race results, pit reports) conveys tension through terse updates like “collision detected” or “position gained,” evoking the solitary focus of a driver’s cockpit. Critically, this lack of depth highlights a flaw: without compelling personalities or lore, themes feel surface-level, more promotional tool for Prost’s brand than immersive tale. Yet, for historians, it captures 1997 F1’s transitional vibe—McLaren’s dominance, Ferrari’s resurgence—transforming simulation into subtle commentary on motorsport’s fleeting glory.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its heart, Prost Grand Prix 1998 loops around classic F1 cycles: qualify, race, pit, and repeat, with modes for full championship, single races, or private testing to hone skills. Core driving mechanics simulate track racing in 1st- or 3rd-person views, emphasizing vehicle physics over arcade flair—though critics decried it as “unrealistisches Fahrverhalten” (unrealistic handling), with cars gliding through corners like “Schwerkraft schwarzer Löcher” (gravity of black holes). Acceleration feels erratic: rapid starts give way to instant traction loss, and steering is asymmetric (left turns under-responsive, right overzealous), demanding a wheel for tolerability but punishing keyboard users. Progression ties to season-long campaigns, where wins unlock hall-of-fame entries, but no deep RPG elements exist; instead, customization drives replayability via an extensive editor for teams, drivers (names, colors, stats), and car setups.

Innovative systems include dynamic weather affecting grip (rain slicks tracks, forcing tire changes) and realism toggles like traction control or ABS, scaling from beginner aids to hardcore simulation. Pit stops simulate crew efficiency, with delays based on strategy, adding tactical depth. UI is straightforward yet “häßlich” (ugly)—clunky menus with non-transparent smoke effects and glued-on sparks, no pop-up but low-detail horizons. Flaws abound: AI is “random,” prone to bizarre crashes; multiplayer is basic (master/slave setup, poorly localized as “Herr und Sklave”); and 3Dfx support yields blocky textures worse than base mode. Combat? Nonexistent, but on-track battles feel chaotic, with editable rival reliability enabling sabotage via “unreliable” foes. Overall, loops are functional for quick laps but lack the nuanced progression of peers, suiting casual spins over endurance marathons.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world is a faithful, if austere, recreation of 1997 F1 circuits—Hockenheim’s stadium bends, Monza’s tree-lined straights—spanning Oceania (Australia), Brazil, France, and beyond, with editable billboards featuring real sponsors for immersion. Atmosphere builds through procedural elements: cheering crowds blur into distant pixels, safety cars deploy amid crashes, and variable weather shifts moods from gleaming daylight grids to misty, hazardous nights (though night racing is absent). Visual direction prioritizes performance over polish—3D models of the AP02 and rivals are blocky, sans sponsor stickers, with “lieblos gestalteten Kulissen” (carelessly designed backdrops) that load swiftly but lack detail, like opaque tire smoke or static sparks. Textures are “grobklotzigen” (crude), especially on 3Dfx, evoking early Quake-era rasterization rather than polished sims. Perspectives enhance this: 1st-person cockpit immerses via a static dash (minimal gauges), while 3rd-person chases the peloton, though limited angles frustrate.

Sound design elevates the experience, courtesy of the AIL/Miles Sound System. Engine roars pulse authentically—V10 wails crescendo on straights—punctuated by gearbox shifts and screeching tires, though some called them “gräßlichen Motorengeräuschen” (gruesome). No commentator is a boon, avoiding dated voiceovers, while La Marque Rose’s soundtrack blends upbeat electronica with tense ambient tracks, syncing to race phases for adrenaline. These elements coalesce into a competent, if sparse, F1 vibe: the AP02’s whine against rival howls builds rivalry, rain patters heighten peril, and post-race anthems reward victories. Ultimately, art and sound contribute a charming, era-specific authenticity—French pride in every rev—but falter in evoking spectacle, making worlds feel more like functional tracks than vibrant spectacles.

Reception & Legacy

Upon 1998 launch, Prost Grand Prix 1998 garnered middling reception, with a MobyGames critic average of 52% from 11 reviews and player scores dipping to 2.8/5 from four ratings. European outlets like PC Joker (70%) praised its speed on modest hardware and value (“für nur 59,- DM verzeiht der Sparer so manches”), deeming it “gut für Einsteiger” (good for beginners) despite graphical shortcuts. Power Unlimited (70%) highlighted ease of play—”je hoeft hier niet dagen te oefenen”—but nitpicked sound. Harsher verdicts came from PC Player (38%), awarding “Preis Nr. 3: die schlechteste 3Dfx-Grafik aller Zeiten” (worst 3Dfx graphics ever), and Power Play (32%), slamming “Dilletantismus” (amateurism) in handling and options. PC Games (28%) noted untapped potential in its physics, ruined by “Fahrhilfen” (driving aids) and poor localization. Commercially, it flew under the radar, a budget title outsold by F1 World Grand Prix (1999) or Grand Prix Legends, appealing mainly to Prost fans amid PGP’s real-world struggles (the team scored no points in 1998).

Over time, reputation has softened into cult obscurity, preserved on abandonware sites like MyAbandonware (4.78/5 user votes) and emulated via DOSBox. Modern retrospectives, like UnracedF1.com, laud its “own little charm” for era enthusiasts, praising editable 1998 vibes and quirky AI (e.g., “J. Heldenview” in “Johnsons”). Influence is minimal—Visiware’s later works like Planet of the Apes (2001) diverged, and it inspired no direct sequels—but it exemplifies 90s F1 tie-ins, paving tangential paths for customizable sims in titles like F1 Manager. In industry terms, PGP underscores licensing pitfalls (editable rosters as a blueprint) and the shift to Windows, remaining a footnote for historians studying F1’s digital boom.

Conclusion

Prost Grand Prix 1998 is a relic of ambition tempered by limitation: Visiware’s earnest simulation captures the editorial freedom and seasonal grind of F1, bolstered by solid sound and low-barrier entry, yet undermined by clunky physics, dated visuals, and incomplete features. It shines as a Prost tribute—evoking the driver’s legacy through editable authenticity—but falters as a contender, outpaced by 1998’s elite. For retro racers or F1 purists, it’s a worthwhile curiosity, playable today via emulation, earning a nostalgic 6/10. In video game history, it occupies a pit lane spot: essential for understanding budget sims’ role in motorsport’s pixelated evolution, but unlikely to lead the pack.