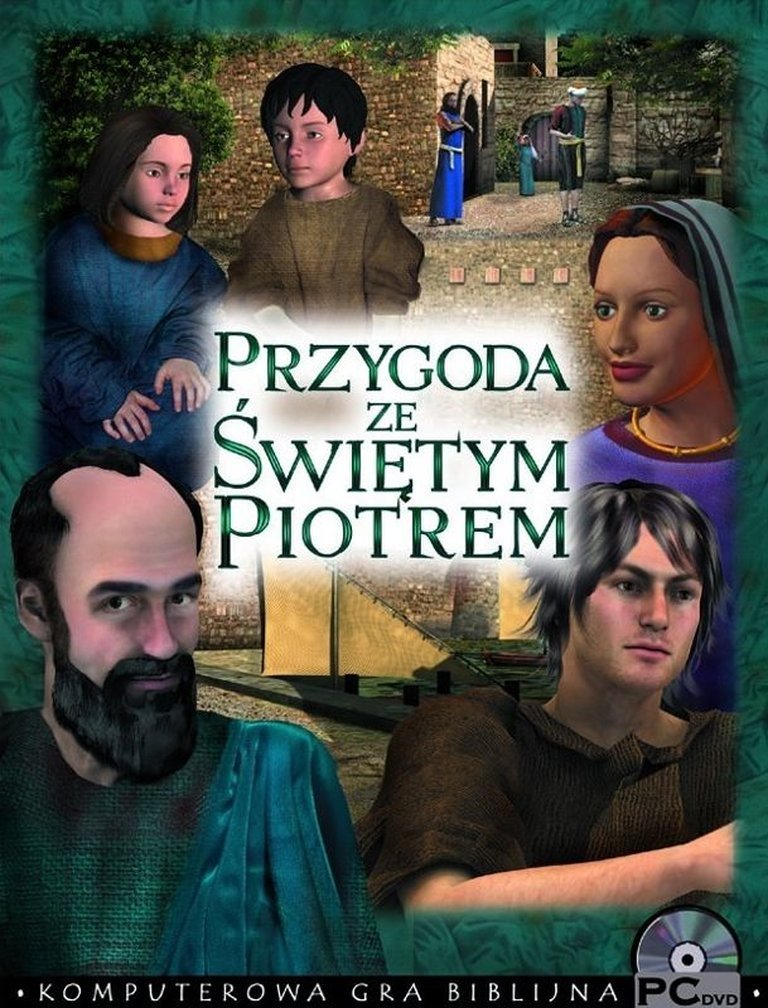

- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Wydawnictwo Pasterz

- Developer: Wydawnictwo Pasterz

- Genre: Adventure, Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Middle East

Description

Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem is a Polish-language educational adventure game developed by Wydawnictwo Pasterz. Set in the Middle East during the 1st century, players control a Galilean resident who meets Saint Peter and joins his journey, learning about the lives of Saint Peter and Jesus through point-and-click interactions and simple puzzles designed for early school-age children.

Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem: A Chronicle of Faith, Pedagogy, and Pixelated Pilgrimage

Introduction: A Niche Forged in Conviction

In the vast, diverse landscape of video game history, certain titles exist not as commercial juggernauts or critical darlings, but as quiet, determined artifacts of a specific cultural and spiritual mission. Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem (“An Adventure with Saint Peter”), released on May 8, 2012, for Windows by the Polish Catholic publishing house Wydawnictwo Pasterz, is precisely such an artifact. It is a game that wears its purpose on its sleeve: a simple point-and-click adventure designed explicitly to educate children about the world of the New Testament through the lens of Saint Peter’s life. To the global gaming press of 2012, a year dominated by releases like Mass Effect 3, Diablo III, and Journey, this modest DVD-ROM title was invisible. Yet, within its intended context—a Polish Catholic household seeking trustworthy, engaging educational software—it represents a significant, if under-documented, effort. This review will argue that Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem is a fascinating case study in constrained, mission-driven game design. Its value lies not in technical innovation or narrative complexity, but in its sincere, coherent execution of a pedagogical vision within the well-worn mechanics of the graphic adventure genre. It is a bridge between ancient scripture and digital interactivity, built with painfully clear limitations yet sturdy, purposeful planks.

Development History & Context: The Pasterz Paradigm

To understand Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem, one must first understand its creator. Wydawnictwo Pasterz (“The Good Shepherd Publishing House”) is not a game studio in the western sense; it is a religious publisher with a multimedia division. Its primary output is books, audio recordings (słuchowiska), and educational materials for the Polish Catholic community. The development of Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem must be seen as an extension of this catechetical mission into the digital realm, following their earlier biblical game, Być uczniem Jezusa (“To Be a Disciple of Jesus”).

The project was helmed by Łukasz Kulisiewicz as the “Informatical Project” lead, with substantive consultation by Piotr Narkiewicz—a name that appears repeatedly in the credits, indicating a small, core team likely wearing multiple hats. The technological constraints of 2012 are palpable. The game was built for Windows, distributed on DVD-ROM, and required minimal specs (1GB RAM, 2GB HDD space). This speaks to a target audience of standard, likely older, home PCs rather than cutting-edge gaming rigs. The choice of the point-and-click adventure genre is both practical and ideological. It is a genre synonymous with thoughtful pacing, dialogue, and puzzle-solving—mechanics that align perfectly with a slow, contemplative, and intellectually engaging approach to its subject matter. It avoids the twitch reflexes and violent connotations of other genres, opting for a UI (point-and-select) that is universally accessible to young children. The game’s existence is a direct response to a perceived gap: a need for safe, values-based entertainment within a specific faith community, created by that community, for that community.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Companion on the Road

The narrative premise is elegantly simple. The player does not control Saint Peter, the apostolic giant, but an unnamed “Galilean resident” (towarzysz Piotra) at the beginning of the 1st century. This design choice is crucial. By placing the player in the role of a peer—a commoner, a companion—the game avoids the daunting, quasi-divine perspective of controlling a biblical hero. Instead, it invites the child player to imagine themselves walking alongside the saint, learning through his example and the world he inhabits.

The plot unfolds across seven distinct stages (etapy), each representing a different location in a reconstructed Galilean town: the port, the market, the town square, underground corridors, and domestic interiors. The structure is episodic, with each stage building towards a key that unlocks the next. This creates a clear, achievable progression loop for a young mind: explore, interact, solve, advance.

Dialogue is the primary narrative vehicle. The game populates its world with two archetypes of non-player characters: those who help and those who hinder. This binary moral framework is appropriate for its early-school-age target, presenting clear choices and consequences. Conversations are not just functional quest-givers; they are the primary means of “show, don’t tell” storytelling. Through interactions with a kowal (blacksmith), cieśla (carpenter), kupiec (merchant), and children at play, the game weaves in details of daily life—studnie (wells), piece do wypiekania chleba (bread ovens), gliniane dzbany (clay jugs), kamienne żarna (stone mills). This anthropological detail is a major strength, grounding the biblical era in tangible, relatable everyday activities.

Thematically, the game is subtler than a direct sermon. While the ultimate goal is education about Jesus and Saint Peter, the narrative is filtered through the companion’s journey. The ” Przygoda, która rozpoczyna się z pozoru bardzo zwyczajnie, wkrótce poprowadzi gracza do miejsc niesamowitych i wydarzeń bardzo dziwnych i tajemniczych” (An adventure that begins very ordinarily will soon lead the player to incredible places and very strange and mysterious events) as described on the product page. This hints at a narrative structure that builds from mundane tasks (finding items, delivering messages) to a sense of escalating wonder or divine encounter, mirroring the disciples’ own journey from confusion to revelation. The role of Maniusia, voiced by the renowned Polish singer Anna Maria Jopek, adds a layer of cultural prestige and provides a clear, friendly guide-figure within the game’s world.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Point-and-Click Catechism

Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem is a purist’s graphic adventure. Its gameplay loop is classical:

1. Exploration: Navigate static, painterly backgrounds using a map that unlocks as locations are discovered.

2. Interaction: Use the cursor to examine environments and talk to NPCs. Dialogue trees are likely linear or branched with clear “correct” paths for puzzle progression.

3. Inventory & Puzzles: Collect items (key, tool, relic?) and use them on characters or environment objects to solve simple puzzles. These are described as “różnorodne zadania, tajemnice i zagadki” (diverse tasks, mysteries, and puzzles).

4. Mini-Games: The addition of mini-games like “krzyżówka” (crossword puzzle) is a notable diversifier. It breaks the point-and-click monotony and introduces a direct knowledge-testing element, reinforcing the educational content in a gamified format.

5. Progression: The seven-stage structure with key-based stage transitions provides a clear, bite-sized structure suitable for children’s attention spans and play sessions.

The systems are intentionally lightweight. There is no combat, no character stats, no complex inventory management. Success is binary: a puzzle is solved or it is not. The UI is transparent—the point-and-select cursor is the only tool. The “innovations” are not mechanical but integrative: the seamless blending of a factual, historically-attuned world (via the background art and photos from the Holy Land) with standard adventure mechanics. The “flaws” are inherent in its simplicity and target audience. There is no failure state, no challenge scaling, no replayability beyond rediscovering the narrative and puzzles. It is a consumable experience, a single path to be followed once or twice. The game’s difficulty curve is designed for gentle, guided discovery, not frustration. Its greatest systemic achievement is the consistent application of its rules within a thematically unified world.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Evoking Galilee, 1st Century AD

This is where the game’s limited budget and focused vision produce unexpected strengths. The world is built from two primary artistic sources:

1. Hand-Painted Backgrounds: Likely created by graphics lead Tomasz Dziuba and Hanna Chodak. These would be stylized, illustrative depictions of a Galilean port, market stalls, and domestic interiors. The style is almost certainly illustrative and warm, aiming for a storybook or historical illustration aesthetic rather than realism or gritty simulation.

2. Photos from the Holy Land: A unique and documented feature. Credits list Beata and Krzysztof Zymonik for “Zdjęcia z Ziemi Świętej.” These photographs are almost certainly used as environmental textures or direct background plates, or perhaps as unlockable gallery content. This is a powerful, if subtle, pedagogical tool. It grounds the fictional adventure in the real geography and archaeology of the region, lending an aura of authenticity and connecting the biblical narrative to a tangible place. A child might see a real photo of a stone arched doorway in Jerusalem and then see a stylized version of it in the game, creating a potent link between story and history.

The setting is meticulously described: a single town with key social hubs (port, market, square) and private spaces (homes, underground storage). The detail in the product description is telling: “Dzieci bawią się ze sobą lub pilnują łodzi, a większość dorosłych zajętych jest pracą (kowal, cieśla, kupiec, sprzedawcy, ogrodnicy).” This is not a grandiose depiction of Jerusalem or the Sea of Galilee; it is the intimate, everyday life of a small town. This scale is perfect for a child’s comprehension and creates a cozy, explorable sandbox.

The sound design is credited to Piotr Soszyński, with music by Marek Kalinowski, Tomasz Kulisiewicz, Jarosław Baliński, and Maciej Litwin. The voice cast is extensive for such a small project (17 named talents), featuring professional actors like Piotr Narkiewicz and Krystyna Labuda alongside pop star Anna Maria Jopek (as Maniusia) and the intriguingly named “Gienek Washable.” This suggests a serious commitment to Polish theatrical voice acting, likely employing warm, clear, and expressive tones suitable for children. The music would be scored for small ensembles or synthesizers, aiming for a Middle Eastern-modal melody mixed with accessible, thematic underscore—evocative without being overwhelming.

Together, these elements create an atmosphere of solemn yet inviting historical education. It avoids the spectacle of games like Assassin’s Creed but achieves a kind of domestic, tactile intimacy. The world feels used, lived-in, because it is populated with specific jobs and objects.

Reception & Legacy: The Quiet Triumph of the Niche

Critical reception for Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem is virtually non-existent in the mainstream, international press. As the MobyGames and Metacritic pages show, there are no professional critic reviews logged. Its “Moby Score” is listed as n/a, and user reviews are scarce (the GRYOnline page shows an average of 2.2/5 from 159 user ratings, but this is aggregated and likely reflects a very small, polarized sample of its actual audience). This obscurity is its default state outside Poland and outside the niche of Catholic educational media.

Its commercial and cultural reception must be inferred from other sources. The fact that Wydawnictwo Pasterz continued to produce and sell the game (it remains listed on their official sklep.pasterz.pl site, with a user review from 2013) indicates it found a sustainable, if small, market. The most concrete measure of its success is the II Nagrodę (Second Prize) at the XXVIII Międzynarodowy Katolicki Festiwal Filmów i Multimediów “Niepokalanów 2013” in the “programy multimedialne” (multimedia programmes) category. This is not a gaming award like the BAFTAs or the Game Awards; it is a Catholic media festival award. It validates the game precisely within its intended community and genre, recognizing its effectiveness as a piece of multimedia catechesis. This award is its primary claim to legacy.

Its influence on the broader industry is negligible. It did not pioneer mechanics, popularize a genre, or impact mainstream development. Its legacy is internal and archival. It is part of a small, persistent lineage of “biblical games” or “faith-based games.” It sits alongside Wydawnictwo Pasterz’s own Być uczniem Jezusa and similar titles from other small, faith-based studios worldwide (like the Left Behind series or many early “Bible software” programs). It demonstrates a viable, if commercially limited, model: identify a specific, underserved audience with clear values and educational needs; utilize a simple, proven game genre (point-and-click); invest in voice acting and authentic details to build credibility and engagement; and distribute through trusted community channels (church bookstores, religious publishers’ websites). It is a testament to the fact that the video game medium can be, and has been, employed for straightforward, didactic purposes long before the “serious games” movement gained academic traction.

Conclusion: A Humble Artifact of Purposeful Play

Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem is not a lost classic waiting for rediscovery. It is not a flawed gem. It is exactly what it set out to be: a competent, sincere, and functionally engaging educational tool for Polish Catholic children in 2012. Its technical achievements are minimal; its narrative, while coherent, is not sophisticated by secular gaming standards. Its puzzles are simple, its world small, its scope intensely focused.

And yet, to dismiss it is to miss its point entirely. Within the context of its creation, it is a success. It translates a sacred text and a historical period into an interactive experience that a child can navigate, using tools (dialogue, exploration, item use) that are themselves part of a classic adventure game lexicon. It leverages the unique affordances of the medium—player agency, spatial exploration, problem-solving—to make a historical-religious world feel visitable. The inclusion of real photographs from the Holy Land is a stroke of pragmatic genius, using the game as a gateway to tangible reality. The star-studded Polish voice cast elevates the production value and ensures a professional, engaging aural experience.

Its ultimate verdict in the history of video games is as a niche artifact of faith-based educational design. It proves that the graphicolor adventure template is robust enough to carry non-secular, pedagogical content. It stands as a quiet counterpoint to the assumption that all games must strive for mass appeal, infinite complexity, or artistic abstraction. Some games are made to teach, to affirm, and to connect a community to its heritage through the simple joy of clicking your way through a story. For the child in a Biestrzyków home in 2012 who explored that reconstructed Galilean town with curiosity, guided by the voice of Anna Maria Jopek, Przygoda ze świętym Piotrem was not just a game. It was a learning journey, a digital catechism, and a testament to the fact that even the most constrained projects can achieve their own modest, meaningful victory. It is a 2.2/5 on a Polish gaming portal, but in the grand, sprawling archive of human play, it holds its own unique, unassailable place.