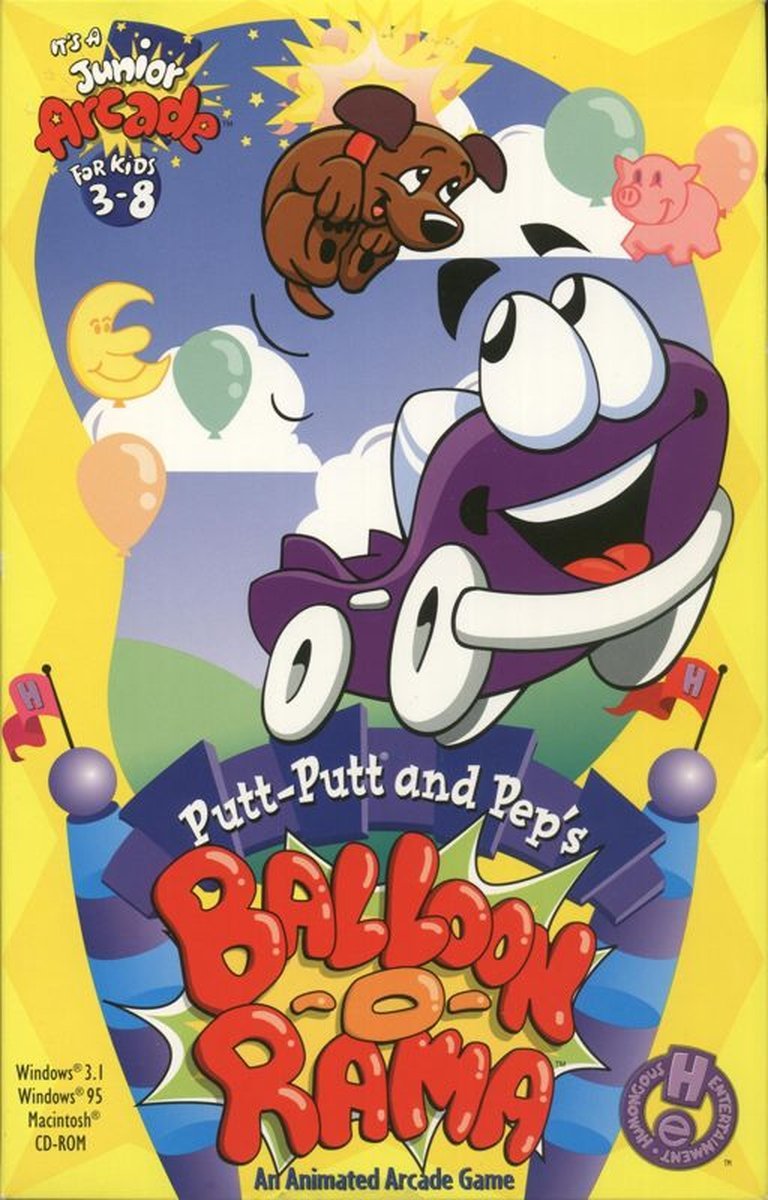

- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: Linux, Macintosh, Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Publisher: Akella, Humongous Entertainment, Inc., Night Dive Studios, LLC, Ravensburger Interactive Media GmbH

- Developer: Humongous Entertainment, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Breakout, Level editor, Pinball, Power-ups

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

In ‘Putt-Putt and Pep’s Balloon-o-Rama’, a 1996 Breakout-style arcade game from Humongous Entertainment, players control the purple car Putt-Putt using the mouse to bounce his puppy Pep across the screen and pop balloons that multiply in vibrant, cartoonish levels. The game features special balloons that provide points, power-ups like Fireman Pep, and color changes, along with a level builder for custom stages, all set in a playful world with an acclaimed soundtrack.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Putt-Putt and Pep’s Balloon-o-Rama

PC

Putt-Putt and Pep’s Balloon-o-Rama Free Download

Putt-Putt and Pep’s Balloon-o-Rama Reviews & Reception

store.steampowered.com (80/100): Humongous gets bonus points for continuity of excellence.

Putt-Putt and Pep’s Balloon-o-Rama: A Deep Dive into Humongous Entertainment’s Junior Arcade Experiment

Introduction: The Purple Car and the Perpetually Bouncing Puppy

In the mid-1990s, the landscape of children’s software was a curious blend of earnest edutainment and simplistic arcade adaptations. Into this space stepped Humongous Entertainment, a studio synonymous with charming point-and-click adventures for kids. Their Putt-Putt series had already established a formula: a friendly purple car, his canine companion Pep, and gentle life lessons wrapped in vibrant, hand-drawn worlds. With Putt-Putt and Pep’s Balloon-o-Rama (1996), the studio made a significant, and ultimately revealing, pivot. It was the inaugural title in their new “Junior Arcade” line—a deliberate move away from overt educational goals toward pure, unadulterated action gameplay, albeit firmly within a non-violent, child-friendly context. This review argues that Balloon-o-Rama is a fascinating, deeply flawed artifact. It stands as a testament to Humongous’ willingness to experiment with genre conventions and accessibility, yet it also exposes the inherent tensions in translating the gentle, narrative-driven ethos of the Junior Adventures into the demanding, systemic world of the arcade Breakout clone. Its legacy is one of stark contradictions: a game praised for its infectious soundtrack and noble intentions, yet often criticized for punishing difficulty, poor balance, and repetition that undercuts its target audience.

Development History & Context: From SCUMM to Simple Action

The Studio and Its Vision: Humongous Entertainment, founded by Ron Gilbert and Shelley Day ( veterans of LucasArts and its legendary SCUMM engine), had built its reputation on point-and-click adventures (Freddi Fish, Pajama Sam). Balloon-o-Rama was part of a strategic branching. As documented in a Humongous press release cited by Wikipedia, the “Junior Arcade” series was explicitly created to offer “fast-and-furious game-play” and action “in a nonviolent context,” targeting kids aged 3 to 8. This was a direct response to market demand for games that felt more like traditional arcade experiences but without the violence or complexity. Lead designer Rhett Mathis, in notes referenced on MobyGames, stated the goal was to “create an animated world of arcade fun and make it kid-friendly.”

Technological Context and the SCUMM Quirk: The game’s technical foundation is a point of minor confusion. While the Putt-Putt adventures famously used a proprietary engine, Balloon-o-Rama is listed on MobyGames and Wikipedia as using the SCUMM engine. This is highly unusual, as SCUMM was LucasArts’ dedicated adventure game engine, not built for real-time physics-based arcade action. The implementation was likely a stripped-down, heavily modified version for handling the 2D sprite-based gameplay, but it speaks to Humongous’ resourcefulness and the fluidity of game tech at the time. The 1996 release on Windows and Macintosh, with later ports to Linux (2014, via Night Dive Studios) and even a drastically simplified LCD handheld (1999, by ToyMax), shows its commercial lifecycle.

The Gaming Landscape: 1996 was the golden age of the Breakout/Arkanoid genre (DX-Ball 2, Ricochet Lost Worlds). Humongous’ entry was unique for its complete integration of a pre-existing licensed character family into this mechanically pure genre. It lacked the power-ups and physics complexity of its contemporaries but compensated with sheer volume (120 levels) and a beloved IP. Its simultaneous release with Putt-Putt and Pep’s Dog on a Stick (another arcade-style game) marked the official launch of the Junior Arcade sub-brand, signaling a major shift in Humongous’ product strategy toward more immediate, replayable gameplay loops.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Plot of Absurd Simplicity

The narrative of Balloon-o-Rama is almost nonexistent, serving purely as a flimsy pretext for the gameplay, yet it is deeply informed by the lore of the Putt-Putt series.

Plot Structure: The Wikipedia entry and MobyGames description outline the story: Putt-Putt and Pep start with a bunch of balloons, which Pep accidentally releases by barking. This triggers a journey across locations from previous Putt-Putt adventures—the zoo from Saves the Zoo, the cave from Joins the Parade—to recapture and pop the multiplied balloons. The journey culminates in a trip to the Moon (recalling Goes to the Moon) via a spaceship. After all balloons are popped, they return to Earth, and Putt-Putt praises Pep’s skills.

Thematic Analysis: The plot is a masterclass in minimalism, yet it reinforces two key themes of the Putt-Putt universe:

1. Non-Violent Problem-Solving: Conflict is replaced with a playful, almost therapeutic task of “popping” balloons. There is no antagonist, no score to beat but one’s own, and failure simply resets the score. This aligns perfectly with Ralph Giuffre’s (Humongous EVP) stated goal of providing “action in a nonviolent context.”

2. Companionship and Responsibility: The entire endeavor stems from Pep’s accidental release of the balloons. Putt-Putt’s role is not as a competitor, but as a supportive partner, using his body to bounce his friend. The dynamic is one of gentle guidance (the player controlling Putt-Putt) and exuberant, slightly chaotic action (Pep). The reward is communal praise, not a trophy. The inclusion of familiar locations acts as nostalgic fan-service for children who played the earlier adventures, creating a cohesive, if geographically nonsensical, world.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Rigors of the Balloon-Bounce

Core Loop: At its heart, Balloon-o-Rama is a Breakout variant, but with a crucial, physics-altering twist: gravity affects Pep. Instead of a ball moving in straight lines, Pep is a bouncing object with an arc. The player controls Putt-Putt’s horizontal movement with the mouse, aiming to have Pep collide with the top of Putt-Putt’s chassis to rebound upward into the balloon field. The goal is to pop all balloons on screen without Pep hitting the ground (losing a life).

Systems & Progression:

* Balloon Types & Power-Ups: The game introduces variety through balloon subtypes. MobyGames’ description and the player review detail:

* Standard Balloons: Pop for base points.

* Candy Balloons: Release candy to catch for bonus points (+50 each).

* Paint-Bucket Balloons: Change Putt-Putt’s color (cosmetic, possibly tied to scoring or power-up effects).

* Question Mark Balloons: Grant temporary power-ups, such as “Fireman Pep” (likely clearing rows) or the notoriously overpowered Cape, which makes Pep stick to Putt-Putt, essentially trivializing control.

* Nested Balloons: Some conceal smaller balloons that must be destroyed.

* Trash Balloons: Deduct points if collected.

* Scoring: The system is multilayered but, as the critical player review astutely notes, profoundly unbalanced. Points from popping single balloons are negligible. The primary scoring path is through combos (popping multiple balloons without Pep touching Putt-Putt), but the strict collision physics (Pep must hit the top) makes sustained combos difficult. High-altitude launches give tiny bonuses. Bonus rounds (triggered by hitting a UFO) offer big scores but have RNG-based spawn timing that often makes them inaccessible near the level’s end. This creates a system where meaningful scoring is only possible in early, easier levels, rendering high scores from later runs largely irrelevant.

* Lives & Difficulty Curve: The game features a brutal difficulty spike. The player review is scathing here: collision detection is unforgiving, requiring Pep to hit the very top of Putt-Putt. Near the bottom of the screen, recovery is nearly impossible. The game provides insufficient extra lives to compensate. The result is a 120-level grind where the final levels are described as “downright cruel,” requiring dozens of attempts. This directly conflicts with the ” kid-friendly” ethos.

* The “Junior Helpers”: This is the game’s most significant and influential design feature. To mitigate frustration for its intended 3-8 age group, two cheats are built-in:

1. Infinite Lives: Prevents game-over.

2. Sticky Pep: Permanently applies the “Cape” power-up effect.

These were revolutionary for the time—a formalized, in-game accessibility option that allowed families to tailor the challenge. As the MobyGames review notes, this feature would become a recurring element in the entire Junior Arcade series, a lasting legacy of Balloon-o-Rama‘s development.

Innovation vs. Flaw: The gravity-based ball physics were an interesting twist on the formula, but the collision precision and combo system’s reliance on perfect physics created a frustrating, imprecise core. The level editor (a “child-friendly UI”) is a notable inclusion that promotes creativity, but the player review correctly observes its limitations—it cannot replicate many official levels’ complexity.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Saccharine Sheen Over Steel

Visuals & Atmosphere: The game uses the classic Humongous hand-drawn art style. Backgrounds are vibrant, detailed, and themed to each level (zoo, cave, lunar surface). Characters are Expressively animated with “paper animation” (a technique mentioned in credits). The atmosphere is playful and bright, perfectly capturing the Putt-Putt aesthetic. However, as a pure arcade game, the world-building is superficial. The backgrounds are static set-dressing; they don’t interact with gameplay. The thematic journey across familiar locations feels tacked-on, a narrative veneer on abstract geometric challenges.

Sound Design & The Legendary Soundtrack: Here lies the game’s undisputed, celebrated triumph. The MobyGames player review calls it “arguably some of the best music in Humongous Entertainment’s history.” Composed and performed by Rhett Mathis (per MobyGames credits; Wikipedia lists George Sanger, likely an error or for a different version), the soundtrack accomplishes a rare feat:

* Catchiness: Melodies are simple, upbeat, and immediately memorable.

* Atmosphere: Each world has a distinct musical theme that reinforces the visual setting (cave music, zoo music, lunar music).

* Variety: The music dynamically shifts based on gameplay state—calmer during setup, more urgent during intense bouncing, triumphant on level completion.

This audio excellence provided a layer of engagement and joy that the sometimes-frustrating gameplay could not match. It’s the primary reason cited for the game’s modern Steam “Very Positive” (84%) rating, with many reviewers citing nostalgia for the music specifically.

Reception & Legacy: A Curious Artifact of Ambition and Misstep

Contemporary Reception (1996-1998): Reviews were mixed but generally favorable for its target audience.

* Electric Playground (80%): Praised “great” graphics, “catchy” music, and its dual nature—catering to both short bursts and obsessive play. It highlighted the continuity of Humongous’ quality.

* AllGame (70%): Called it addictive like Tetris and fun for adults, emphasizing its broad appeal.

The press largely focused on its charming presentation, accessibility via Junior Helpers, and the novelty of a non-violent action game from a trusted kids’ brand.

Modern & Analytical Reception: The 2020 MobyGames user review by “SomeRandomHEFan” provides a blistering, detailed critique that has become the defining analytical take for many modern players revisiting the game. Its points are damning:

1. Excessive Length: 120 levels with insufficient mechanical variety.

2. Unforgiving Difficulty: Precise collision, poor life economy, and cruel late-game design make it hostile to its child target without Junior Helpers.

3. Broken Scoring: An imbalanced, largely irrelevant system.

4. Poor Power-Up Balance: The Cape is game-breaking.

This modern analysis reveals a game whose design is at war with itself: it wants to be a long-form challenge for score-chasers but lacks the systemic depth to sustain it, and it wants to be kid-friendly but imposes brutal mechanical demands.

Legacy and Influence:

* The “Junior Arcade” Prototype: Balloon-o-Rama defined the template: simple arcade mechanics, licensed Humongous characters, and, most importantly, the formalized Junior Helper accessibility options. This template was applied to subsequent titles like Putt-Putt and Pep’s Dog on a Stick and Freddi Fish/Pajama Sam spin-offs.

* A Cul-de-Sac in Genre Evolution: It did not spawn a wave of imitators. Its specific fusion of a tight-but-flawed Breakout clone with a heavy-handed edutainment brand was not a winning formula. The rise of casual mobile games (Angry Birds, etc.) would later perfect the “simple physics-based action” genre in ways Balloon-o-Rama only gestured at.

* Cult Nostalgia Artifact: Its modern reappraisal on Steam (84% Very Positive from 50 reviews) is less about its design and more about nostalgia for its aesthetic and soundtrack. It is remembered fondly as a piece of childhood ambiance, not as a pinnacle of game design.

* Historical Footnote: It represents a moment where a major children’s software studio attempted to bridge its narrative adventure identity with the mainstream arcade market, using its flagship IP as the test vessel. The experiment was only a partial success, leading Humongous to eventually retreat to their adventure-game strengths before their eventual closure and asset sale.

Conclusion: A Flawed Gem in the Humongous Pantheon

Putt-Putt and Pep’s Balloon-o-Rama is a game of profound contradictions. It is a brutally difficult game that claims to be for preschoolers. It is a repetitive 120-level grind with a broken scoring system. Its core physics are imprecise yet demand pixel-perfect execution. And yet, it is buoyed by one of the most infectious, atmospherically perfect soundtracks in 90s children’s software, wrapped in the warm, familiar art of the beloved Putt-Putt series.

Its historical significance lies not in its gameplay excellence, but in its conceptual ambition and its accidental innovation. It formally introduced the “Junior Helper” accessibility paradigm to the industry—a quiet revolution in making games playable for families with diverse skill levels. It stands as a clear marker of Humongous Entertainment’s attempt to diversify beyond point-and-click adventures, an attempt that ultimately exposed the limitations of applying their gentle, character-driven lens to the demanding world of arcade action.

Verdict: A historically important but mechanically troubled artifact. It is not a “good” game by objective design standards, but it is an essential study for understanding the design tensions in children’s software, the evolution of accessibility features, and the power of audiovisual presentation to mask—or at least soften—fundamental gameplay flaws. For the historian, it is a crucial puzzle piece. For the modern player, it is a nostalgic, often frustrating, but oddly charming relic best enjoyed with the Junior Helpers turned on, volume up, and a hefty dose of historical empathy.