- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: RetroSpec

- Developer: RetroSpec

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person, 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 72/100

Description

Quazatron is a sci-fi action shooter where players control KLP-2, nicknamed ‘Klepto,’ a robot dispatched to an underground citadel on the planet Quartech to disable swarms of hostile alien droids patrolling its multi-level floors. Equipped with ranged weapons, ramming capabilities, and a grapple system that triggers a tense mini-game to override enemy circuits, Klepto can destroy foes by shooting, colliding to unbalance them off heights, or salvaging parts like enhanced power units, drives, and chassis to upgrade abilities and navigate lifts between levels in this Paradroid-inspired robot battle adventure.

Quazatron Free Download

Reviews & Reception

old-games.com : Quazatron is a great remake of Hewson’s unique action/puzzle game that is widely considered one of the best 8-bit games of the era.

Quazatron: A Timeless Robotic Rampage in Isometric Splendor

Introduction

In the golden age of 8-bit computing, when silicon dreams clashed in the form of rival microcomputers, few games captured the thrill of mechanical mayhem quite like Quazatron. Released in 1986 for the ZX Spectrum, this isometric action shooter thrust players into the role of a rogue droid dismantling an army of hostile machines in sprawling underground citadels. Drawing inspiration from the Commodore 64’s Paradroid, Quazatron transformed its predecessor’s top-down tactics into a pseudo-3D spectacle of strategy and destruction, cementing its status as a Spectrum essential. As a game historian, I’ve revisited countless retro titles, but Quazatron‘s blend of tense patrols, clever part-swapping, and emergent chaos remains intoxicating. This review argues that Quazatron isn’t just a worthy adaptation—it’s a superior evolution that pushed the Spectrum’s limits, influencing robot-themed gameplay for decades while earning its place as a cornerstone of British gaming ingenuity.

Development History & Context

Quazatron emerged from the fertile creative partnership of Graftgold, a boutique UK studio founded by programmers Steve Turner and Andrew Braybrook in the early 1980s. While Braybrook had already dazzled the Commodore 64 crowd with Paradroid in 1985—a runaway hit praised for its innovative droid-transfer mechanics—Graftgold eyed the ZX Spectrum market, then the dominant force in British home computing. The Spectrum, with its rubbery keyboard and attribute-clash-prone display, couldn’t replicate Paradroid‘s smooth scrolling or vector-style graphics without compromise. Enter Steve Turner, the project’s lead designer and coder, who repurposed his isometric engine from the unreleased Ziggurat prototype to reimagine Paradroid‘s core loop in a flip-screen, 3D-like format.

Published by Hewson Consultants—a prolific outfit known for high-octane titles like Exolon and Cybernoid—Quazatron launched on April 28, 1986, at £8.95, amid a booming era for Spectrum software. The mid-80s gaming landscape was a battlefield of platform rivalries: the C64 boasted superior sprites and sound, but the Spectrum’s affordability and massive user base (over 5 million units sold) made it the UK’s arcade-at-home king. Technological constraints shaped Quazatron‘s vision; Turner’s engine sacrificed fluidity for depth perception, allowing environmental hazards like ramps and ledges that added tactical layers absent in Paradroid. Braybrook contributed conceptual oversight, ensuring the grapple mini-game echoed his original, but Turner infused it with Spectrum flair—facial animations inspired by Braybrook’s earlier Gribbly’s Day Out. Hewson marketed it as the “Spectrum equivalent” of Paradroid, capitalizing on cross-platform buzz, though early previews noted jerky scrolling issues (promised fixes arrived post-launch). This context highlights Quazatron as a testament to adaptive creativity, turning hardware limitations into innovative gameplay during a time when British devs like Graftgold defined the isometric genre alongside titles like Head Over Heels.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Quazatron eschews verbose storytelling for a lean, sci-fi premise that unfolds through gameplay, a hallmark of 1980s action games where lore emerges from mechanics rather than cutscenes. You command KLP-2, affectionately dubbed “Klepto” (from the Greek for “steal,” nodding to its pilfering nature), a reprogrammed droid dispatched by unseen human creators to infiltrate the planet Quartech’s subterranean fortresses. These citadels, starting with the titular Quazatron and progressing to punny locales like Beebatron (a jab at the BBC Micro), Commodo (Commodore), and Amstrados (Amstrad), teem with rogue alien robots gone haywire—perhaps a subtle allegory for AI uprising in an era fascinated by Blade Runner and Terminator.

The “plot” is minimal: Klepto must systematically deactivate every hostile machine across multi-level complexes, accessed via scattered lifts, until the lights dim and victory chimes. No branching narratives or moral dilemmas here; instead, themes revolve around hierarchy and predation in a robotic ecosystem. Enemy droids bear two-letter codes like “B7 Battle Drone” or “R8 Repair Drone,” denoting role (B for battle, R for repair) and rank (1-9, from elite cyborgs to lowly devices), creating a caste system where lower-ranked foes are cannon fodder and alphas demand respect. Special Easter eggs, like the “ST Programmer” (Turner himself) or “AB Andrewoid” (Braybrook), inject meta-humor, poking fun at the dev duo’s rivalry-fueled collaboration.

Deeper themes explore theft and evolution: Klepto’s grapple mechanic symbolizes cybernetic dominance, overriding enemy circuits in a tense mini-game that mirrors neural battles. Salvaging parts isn’t mere power fantasy—it’s survivalist scavenging, reflecting 80s anxieties about technology’s disposability. Dialogue is absent, but in-game info points dispense terse logs on droid behaviors, building immersion without overwhelming the Spectrum’s 48K constraints. Compared to Paradroid‘s spaceship infiltration, Quazatron‘s citadel-hopping evokes a more personal, claustrophobic rebellion, thematizing isolation in a machine-dominated world. It’s sparse but effective, letting player agency drive the “story” of one droid’s ascent from underdog to overlord.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Quazatron is a masterful deconstruction of robotic combat, blending shooter precision with strategic disassembly in flip-screen isometric arenas. Each level is a labyrinth of platforms, ramps, and chasms, patrolled by 20-50 droids whose AI follows predictable yet deadly routes—utility bots trundle aimlessly, while security units hunt aggressively. The primary loop: scout via a mini-map (unlocked by detectors), prioritize threats, eliminate them, and salvage upgrades before power drains or damage mounts.

Destruction offers four synergistic methods, encouraging experimentation. Blasting with weapons (from basic Pulse Lasers to devastating Disruptors) is straightforward but power-hungry, rewarding careful ammo management. Ramming leverages physics: your droid’s mass and speed can shunt enemies off ledges for instant kills, a Ziggurat-engine innovation that adds verticality absent in Paradroid. Collisions risk self-damage, tying into the chassis system’s durability. The grapple, however, is the star—a contact-based override triggering a circuit-board mini-game where you and the foe compete to connect nodes with limited power pulses. Success (measured by dominance ratio) lets you loot intact parts; failure ejects you, vulnerable. This sub-game, visually akin to Paradroid‘s but faster-paced, demands twitch reflexes and pattern recognition, with victories yielding probabilistic hauls.

Progression shines through modular customization: defeated droids drop salvageable components—Power units (Chemifax Mk1 to Cybonic Mk2) fuel everything but add weight; Drive systems (Linear Mk1 to Ultragrav) boost speed at power cost; Chassis (Duralite to Coralloy Mk2) absorb hits; Weapons scale from lasers to plasma. Devices like Overdrive (temporary speed burst), Laser Shields, or Ram Thrusters enhance builds, while the Detector reveals map fog. Weight affects overall agility, forcing trade-offs— a tanky setup plods but survives, a nimble one zips but crumbles. Damage eschews bars for expressive facial cues (blinks for minor, grimaces for critical), inspired by Braybrook’s animations, adding personality. UI is clean: a status panel shows loadout, power gauge, and face icon; controls (cursor keys, Kempston joystick support) are intuitive, though the flip-screen transitions can jolt during pursuits.

Flaws exist: scrolling is “slow and jerky” per critics, exacerbated by the engine’s demands, and later levels swarm with respawning foes, testing patience. Yet innovations like environmental kills and part synergy create emergent depth—push a repair drone into a charger for ironic irony, or build a ram-focused behemoth for boss-like command droids. Multi-citadel progression resets upgrades on death (reverting to defaults), heightening tension, while recharge stations and info points offer breathing room. Overall, it’s a tight, addictive loop that rewards mastery, outpacing Paradroid in customization while retaining its tactical soul.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Quazatron‘s universe is a stark, utilitarian sci-fi dystopia: vast underground citadels pulse with industrial menace, their multi-tiered layouts evoking vast, echoing factories overrun by machines. Levels vary—early ones feature open floors for maneuvering, later add catwalks, pits, and teleporters—fostering paranoia as droids’ patrol paths intersect unpredictably. Atmosphere builds through isolation: dim lighting flickers out upon clearance, symbolizing reclaimed space, while lifts ferry you between floors with tense loading screens. The isometric view, borrowed from Marble Madness-esque illusions, enhances depth, making falls feel vertiginous despite the Spectrum’s 256×192 resolution and color clash.

Art direction maximizes hardware limits: sprites are crisp, multi-frame animations—Klepto’s emotive face cycles through 16 expressions, humanizing the tin can protagonist. Enemies’ blocky designs convey purpose (spindly repair bots vs. hulking battle units), with subtle details like blinking lights adding life. The grapple mini-game’s circuit board glows in stark contrasts, while salvage screens display modular swaps like a cybernetic IKEA catalog. No parallax scrolling, but the flip-screen mechanic creates rhythmic pacing, turning each room into a tactical arena.

Sound design, via the Spectrum’s piercing beeper, is rudimentary yet evocative: sharp laser zaps, metallic rams, and a urgent grapple theme (beeps mimicking electronic warfare) heighten urgency. No music beyond a title jingle, but effects layer tension—droid alerts chirp ominously, power drains whine. This austerity amplifies immersion: in a silent citadel, every clank echoes dread. Collectively, these elements craft a cold, mechanical claustrophobia, where visuals and audio reinforce themes of robotic alienation, making triumphs feel earned amid the grind.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Quazatron was a critical darling, heralded as a Spectrum triumph over C64 envy. Crash awarded 94% in June 1986, lauding its “addictiveness and playability” despite scrolling gripes, dubbing it a “Smash.” Your Sinclair gave 9/10, praising the “original scenario” blending action and strategy, while Sinclair User named it a “Classic” with 5/5 stars. Computer & Video Games (91%) and ZX Computing echoed the acclaim, voting it 4th in Crash‘s 1986 Readers’ Awards for Best Overall Game. Commercially, it sold solidly via Hewson’s mail-order and retail push, bolstered by budget re-releases in compilations like Five Star Games 2. Minor criticisms—jerky movement and steep difficulty—faded against its replayability, landing #19 in Your Sinclair‘s 1993 Top 100.

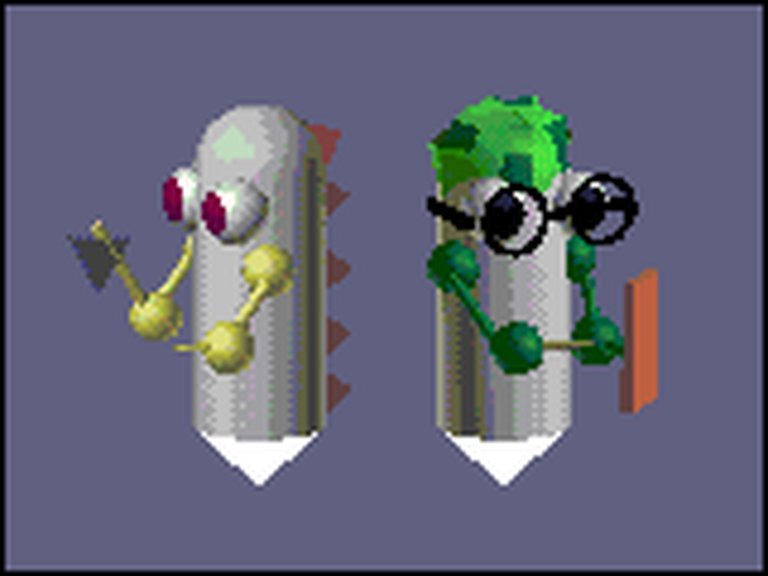

Over time, reputation solidified as a retro icon. Retrospective retrospectives, like Crash‘s 1988 “Run It Again” (81%), called it superior to Paradroid for its fusion of arcade and strategy. A 1988 sequel, Magnetron, iterated on magnetic themes but underperformed (per Turner), while Turner’s Ranarama (1987) borrowed power-up mechanics. Influence rippled: the grapple mini-game inspired control-transfer in later titles like Repton Infinity, and modular robots echoed in Syndicate or modern roguelites like Cogmind. Freeware PC remakes proliferated, notably RetroSpec’s 2003 Windows version by Matthew Smith— a full 3D overhaul with smooth perspectives and Delphi engine, preserving the 1986 essence while modernizing visuals (MobyGames notes its freeware status and Paradroid ties). Though unranked critically (one player score of 2.6/5), it revived interest among emulators. Today, Quazatron symbolizes 80s innovation, archived on sites like Spectrum Computing and influencing indie isometric shooters. Its legacy endures in preservation efforts, proving small-scale brilliance shapes industry DNA.

Conclusion

Quazatron stands as a pinnacle of ZX Spectrum design—a clever riff on Paradroid that alchemized technical hurdles into gameplay gold. Its sparse narrative belies rich themes of mechanical Darwinism, while mechanics like grappling and salvaging deliver endless strategic depth amid isometric chaos. Art and sound, though constrained, forge an atmospheric tension that captivates retro and modern players alike. Critically adored and enduringly influential, from Magnetron to 2003’s 3D remake, it exemplifies how British devs like Graftgold punched above hardware weight. In video game history, Quazatron claims a definitive spot: not just a classic, but an essential artifact of 8-bit rebellion. Verdict: 9/10—timeless, addictive, and unmissable for any strategy-shooter aficionado. Fire up an emulator; Klepto awaits.